Meditations on Celan

Click here to read the rest of the Paul Celan folio.

“Du darfst” / “You may”

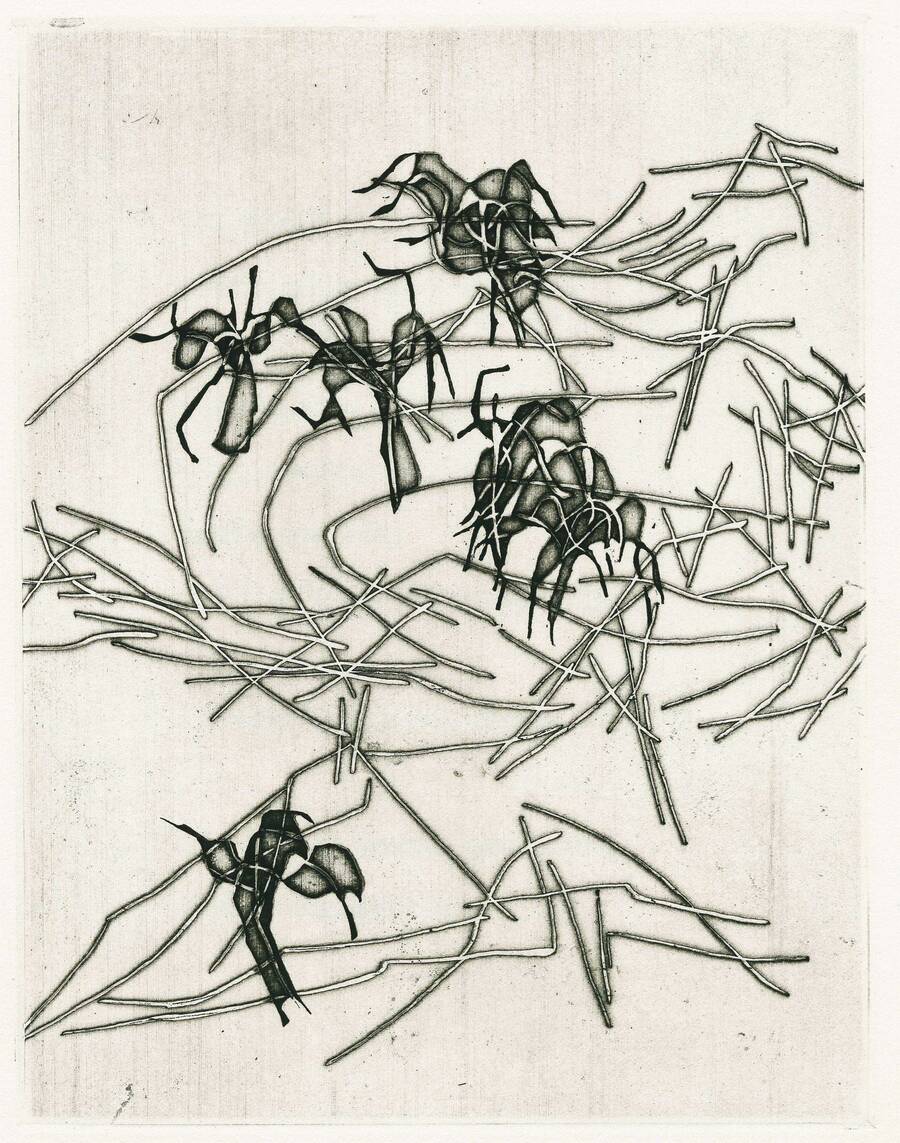

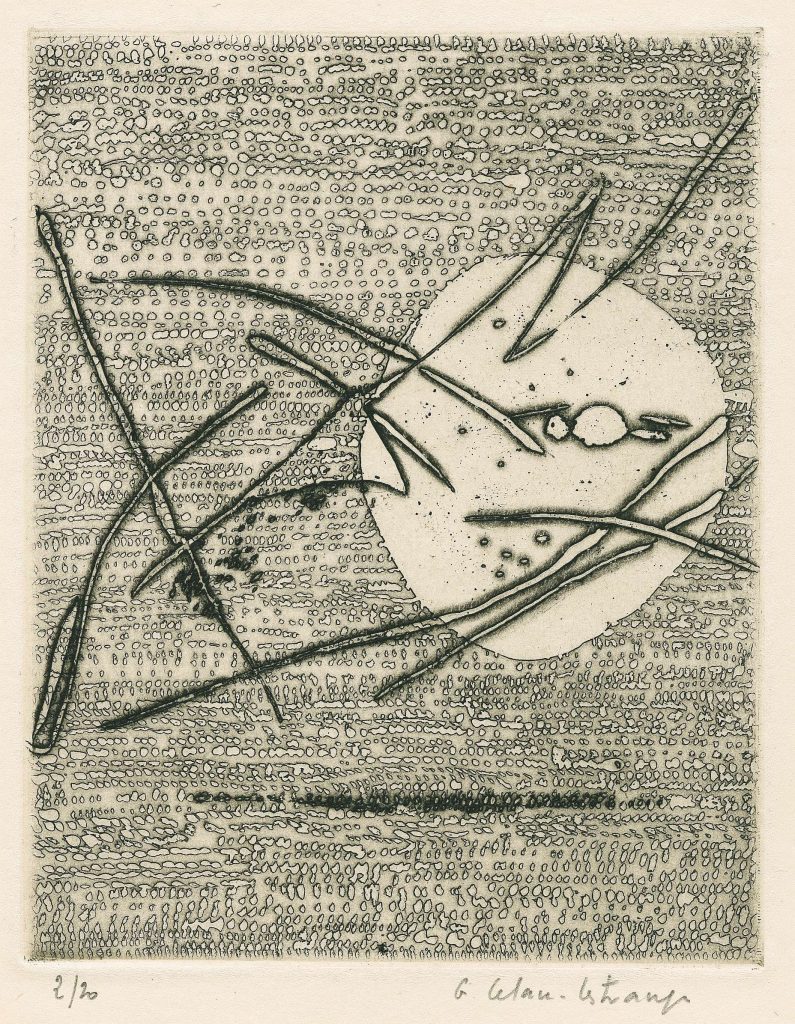

I LOVE TO STRUGGLE over Paul Celan’s “You may,” the first poem in the “Atemkristall” cycle—21 short poems inspired by the etchings of his wife, Gisèle Celan-Lestrange—which opens his 1967 collection, Breathturn. I am in thrall to it. Each reading leaves me confused, and hungry for more. I read and reread the poem. Interpretations emerge, conflict, and combine; images become clear only to grow fuzzy; the poem folds back in on itself over and over, while the confusion—and the hunger—only compounds. As the philosopher Hans-Georg Gadamer writes in an epilogue to his book of essays on the poet, translated by Richard Heinemann and Bruce Krajewski: “Celan’s word choices venture upon a network of linguistic connotations whose hidden syntax cannot be acquired from anywhere else but the poems themselves.” Untangling the relations that populate “You may” is indeed a futile effort. Instead, we must dwell in the knots.

The poem begins with an offering. In Pierre Joris’s translation: “You may confidently / serve me snow.” Immediately, I am both implicated—called into the poem by the “you”—and destabilized: Who exactly is the “you,” the “me”? Already, the proliferation of possible interpretations frustrates any attempt at reading as extracting definitive meaning. Even the seemingly concrete image of snow—which, as Joris notes in the commentary to Breathturn into Timestead, both opens and closes this cycle of poems—is put into question. Is snow even snow at all? Might it be the ash spewed by Nazi crematoria? Or precipitation mixed with smoke—as in the early poem “Black Flakes,” an elegy for his mother, in which the Ukrainian winter serves as an emotional and physical backdrop for his grief? There is no single answer. This multivalent imagery keeps the poem alive—“a question that ‘stays open,’ ‘does not come to an end,’ that points toward the open, empty and free,” as Celan writes in his speech “The Meridian.”

As the metaphor-laden language of seasons continues to perplex, I find myself deeply vulnerable to surprise. The poem’s depictions of nature, both beautiful and stygian, act as a foil for the poet’s internal landscape. In the following lines, warmer months, bustling with budding abundance, remain in the past tense: “as often as shoulder to shoulder / with the mulberry tree I strode through summer.” The mulberry walks along, “shoulder to shoulder” with the “I,” and I think of safety, of company. I feel good in this space. Then, the peaceful scene careens into horror: “its youngest leaf / shrieked.” The endlessly germinating mulberry (once silent witness to the tragedy of Thisbe and Pyramus, the Roman precursors of Shakespeare’s doomed couple, who killed themselves beneath a white mulberry tree and forever stained the fruit with their blood), now, in the midst of our pleasant summer stroll, screams new growth into the world. Each time I read the word, “shrieked” sends me from my shoes.

Reading Celan, I enter poetry’s destabilized terrain. Shoulder-to-shoulder, the poem and I learn a little more about each other. The poem reaches out, maddeningly polysemous, and I am taken into its world. This is not a comfortable world. It is not a place where I can wade easily, letting the language wash over my skin. Rather, it’s a zone in which ordinary hermeneutics no longer serve, where stranger connections must be made. Celan begins his book with a poem that refuses to cater to presumption, that demands a confrontation with my own associative leaps and incomprehension. The poem is there to serve us snow: to muddy our knowledge, to keep us questioning.

—Chase Berggrun

“Sprachgitter” / “Speechgrille”

WHEN WE STUDIED Celan’s mysterious, hermetic poetry in high school in my small, Catholic German hometown—where the people I felt closest to were the dead, and where, lost and lonely, I sought refuge in notebooks and soft paperbacks of modernist literature—I felt a door open in me: to the possibilities of language, and, in particular, to the political dimensions of writing in a language in which I, as a foreigner and child of refugees, felt displaced and alienated. Celan helped me imagine a home in poetry by showing me that one can defamiliarize the world of words.

A couple years later, I found Celan’s poem “Sprachgitter.” Even the poem’s title is encoded with his cryptic re-imagination of language’s bounds. It combines “Sprache,” the German word for language, with “Sprechgitter,” which refers to the dark, barred windows built into the outermost wall of medieval European monasteries, through which Catholic nuns could communicate with the outside world. (Before writing the poem, Celan had received a postcard depicting the only remaining medieval Sprechgitter in the Klarissenkloster in the town of Pfullingen.) Because the nuns were meant to literally refuse the outside world, these Gothic screens were hung with cloths and studded with nails to make touch and even eye contact difficult. In the particular cloister depicted on Celan’s postcard, the nuns kept a vow of silence. On the rare occasions that they were allowed to speak––to providers, teachers, or family––they had to do so through the barred window. The nun’s dark, ascetic life of silence pressed up against that Gothic iron window seems like a heartbreaking allegory for Celan’s predicament: How does a Jewish poet, who lost both his parents in the Holocaust, write poems in German? Because the poet turns Sprechen (speaking) into Sprache (language), the Gitter, a lattice or a grid, becomes the image of language itself, an interface between the cloistered poet and the world beyond.

“Eye’s roundness between the bars,” the poem begins. What the eye—a recurring image in Celan’s work—has seen and witnessed is incommunicable to the other. The poem’s lyric exactness enacts the challenge of speaking through the grid—what the speaker and addressee want to tell each other must be strained and maimed, reformed into dactyls, until it can pass through that almost impassable mesh. In the first stanza, the eyelid flutters upward, as if looking up to a companion, or God. The world remains “heart-grey” as the interior of the Gothic monastery. But there is a moment of hope and recognition, a gesture toward intimacy: In parentheses, the speaker reminisces that the you and I of the poem have briefly met beneath passing winds, even if they remain strangers. The chiastic opposition is without resolution: “If I were like you. If you were like me . . . ” They are not like each other, and hence they end as “two / mouthfuls of silence”; each party must, perhaps, return inward again. Celan’s language is tight, otherworldly, full of assonances; and because of the many consonants and connotations, the words feel almost tactile—as if Celan’s strange images and sounds could touch the reader. So often, when language seems to fail me—when I am grieving, or in terrible isolation, as I was those many years ago—I turn to poetry, to name the unnamable, to be understood, to feel held.

Sometimes, when I try to preach the brilliance of Celan to those who don’t speak German, I find myself at a loss for words. More than any other poet’s, his work is haunted by the ghosts of this language. But, of course, his sheer popularity in translation attests to the impossible: What Celan does to language does not only transform, but also transcends German. Through magic and craft, his poems permeate the unbearable iron lattice—his words fluttering like music, like touch.

—Aria Aber

“Psalm” / “Psalm”

THE KAFKAESQUE AXE came down through the frozen twenty-two-year-old sea within me. A friend had told me about Michael Hamburger’s translations of Paul Celan’s poems, just out from Persea Books, and they’d gotten into my blood like little else I read then did. Something inexplicably familiar about the foreignness of the poems took hold, pulse-beat by increasingly syncopated pulse-beat, and though I couldn’t recognize it as such at the time, that something emerged from their being not just charged English translations but, at heart, translations of translations: a series of ghostly, redoubling displacements accounting for a presence that felt, and remains, somehow more resonant and intimate for all its remoteness.

No one moulds us again out of earth and clay,

no one conjures our dust.

No one.Praise be your name, no one.

For your sake

we shall flower.

Towards

you.A nothing

we were, are, shall

remain, flowering: . . .

I found myself reading this while driving, being driven by what I read—the book propped against the steering wheel—its life in my hands and mine in its, along with “the nothing-, the / no one’s rose” it was offering me. I couldn’t get enough of it, those overpowering echoes of absence and too-muchness: “With / our pistil soul-bright, / with our stamen heaven-ravaged, / our corolla red / with the crimson word which we sang / over, O over / the thorn.”

The materials of baseline and terminal significance were being dismantled and recomposed on the page before me. Words split open, onto an abyss where vocabularies, lives, and theologies collided, fused, exploded—Jewish and Christian, ancient and modern, Germanic, Hebraic, English, and American. “[S]ay of what you see in the dark, // That it is this or that it is that, / But do not use the rotted names,” writes Wallace Stevens, as though he had the future of Jewish poetry in mind. Celan takes up a debased mother tongue (German) and hears it through warps of his childhood Romanian, Hebrew, and Yiddish, as well as the French of his day-to-day life in Paris, so that all seep inevitably into its old-new music of deprivation and desire.

Here, opening onto an abyss within me, was a believable postmodern liturgical poetry for a poet-reader whose synagogue consisted almost exclusively of ink (though he hadn’t yet found Cynthia Ozick’s “print is all my Judaism”). Celan’s “Psalm,” like so many of his poems, precipitates an impossibility, which the translation raises, in its fashion, to a questionable higher power: Turn it and turn it, everything seems to be carried within its caustic purities. Everything and Nothing, syllable by broken, burrowing, burgeoning syllable. Ultimate futility and ultimate reality, Eros and irony, howl and hymn, all of history, and a tangible sense of a vital, not-quite-nameable force at once beyond it and at its core.

—Peter Cole

“Mit den Verfolgten” / “With the persecuted”

IT’S POSSIBLE—perhaps impossible not—to translate every word of a Paul Celan poem, and capture nothing of what matters in it. Given that Celan wrote to defeat one language (German), it’s not surprising that his words defeat translation into others. Putting a poem into a different language, no blame attaches to the translator, except inasmuch as she is knowingly purveying something almost entirely useless. This gives rise to what I’d call physical translation—translation as silhouette, translation as empty promise. It works best from the other side of the room. It’s the difference between a can of tomatoes and a can of air.

Here is Pierre Joris’s “With the persecuted”:

With the persecuted in late, un-

silenced,

radiating

league.

The morning-plumb, gilded,

hafts itself to your co-

swearing, co-

scratching, co-

writing

heel.

There is not a word here that one could take issue with, except possibly “hafts,” taken rather supinely from the German “heftet” and not a verb in English, other than in the rare and unusual sense of “furnish with a haft or handle.” The morning-plumb has—really?—hafted itself? Here is the German: looks identical, same number of words—well, one less; the German has an extra article—same hyphenated breaks, same commas. Take a few steps back, same poem, two whittlings, each coming to the point of a single monosyllabic word:

Mit den Verfolgten in spätem, un-

verschwiegenem,

strahlendem

Bund.Das Morgen-Lot, übergoldet,

heftet sich dir an die mit-

schwörende, mit-

schürfende, mit-

schreibende

Ferse.

One negotiates the poem, the strenuous adjectival participles in apposition (so much drabber in uninflected English), wondering what is being said. As often, Celan is wondering how and where to align himself. “Mit,” in the sense of making common cause with. He is on the side of the pursued, the persecuted, like Heinrich Heine, his 19th-century German Jewish poet predecessor, who wrote: “My ancestors were not to be found with the hunters, but the hunted.”

But with the last word, “Ferse,” heel, any neat alignment with a common cause unravels. Homophonically, “Ferse” is “Vers” is lines of verse is poetry. Once you’ve read that, the poem unmakes and remakes itself. It’s the poem that is writing and scraping and conspiring along; the thing that takes to its heels and makes common cause with the pursued or the persecuted is a poem. By analogy, “Bund,” which closes the first stanza, brings to mind the “gebunden” of a bound book, and “heftet” the “Heft” of a notebook. “Bund”—a homophone with “bunt,” meaning bright or colorful—also functions as part of a pair of chromatic puns, along with the neologism “Morgen-Lot,” which plays on the much more common “Morgenrot,” meaning dawn-red. The poem squares a certain gaiety—it’s not a gloomy piece—with its earnest ethical-political purpose, ominous coding, and—pun intended—guilt. Survivor’s gilt. Survivor’s tilth. Because a further line of ambiguity connects “Morgen” (which can also mean an “acre”) with the suggestion that the poem is what accretes under the heel of the fugitive, the refugee. He is plumbing the mud, the earth. The “Morgen-Lot.” The “Vers” is what comes about under the “Ferse.” As Whitman wrote, “if you want me again look for me under your boot-soles. // You will hardly know who I am or what I mean, / But I shall be good health to you nevertheless, / And filter and fibre your blood.”

—Michael Hofmann

Chase Berggrun is a trans woman poet. She is the author of R E D (Birds, LLC, 2018). Her work has appeared in American Poetry Review, Poetry, Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day, and elsewhere.

Michael Hofmann is a poet and translator. His newest book of poems, One Lark, One Horse, came out in paperback last summer. Messing About in Boats, a collection of his Clarendon lectures, was recently released by Oxford University Press.

Peter Cole’s most recent book of poems, Draw Me After, is just out from Farrar, Straus and Giroux.