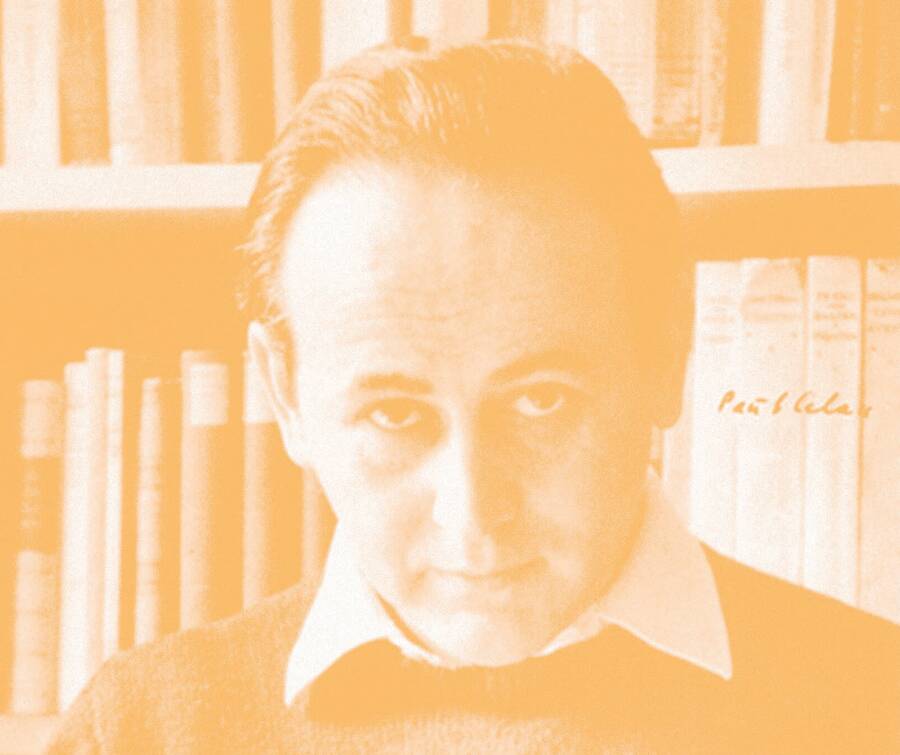

Celan at 100

LAST YEAR marked the centennial of the birth of Paul Celan, who wrote some of the most potent and haunting poetry of the 20th century. Celan—born Paul Antschel in Czernowitz, Romania (now part of Ukraine) in 1920—lived a life scarred by personal and historical tragedy. In 1942, his parents were taken to a Nazi concentration camp, where they both died; Celan himself survived eighteen months in a labor camp. These experiences, especially the murder of his mother, cast a long shadow over the rest of his life, and deeply informed his poetics.

In the last years of the war, Celan moved to Bucharest, then Vienna, before settling in Paris in 1948. That same year, he published his first book of poems, Der Sand aus den Urnen (The Sand from the Urns). Celan wrote in German—a tongue to which he felt inextricably and complicatedly bound, both because of his mother’s love for the language and because of its relationship to Nazi violence. It became his lifelong project to ask: What can poetry do in the wake of unspeakable horror, when the language and the horror are irrevocably enmeshed?

One of his first explorations of this question was the poem “Todesfuge” (“Deathfugue”), which first appeared in The Sand from the Urns. Here, Celan links the horrors of the death camp to “Schwarze Milch” (“black milk”), an image borrowed from the poet Rose Ausländer. The poem begins (in Pierre Joris’s translation):

Black milk of morning we drink you evenings

we drink you at noon and mornings we drink you at night

we drink and we drink

we dig a grave in the air there one lies at ease

“Todesfuge” quickly became one of the most widely taught and anthologized German poems about the Holocaust. Its popularity was accompanied by sanitized misinterpretations—some Germans read absolution and healing into the poem, which particularly vexed Celan—and he eventually renounced its poetics as too musical, too beautiful, for the horrors described. In his middle period and later work, his poetry becomes sparer, less lyrical, hollowing out the German and shattering its syntax—wrecking to reimagine—as in “Engführung” (“Stretto”), a rewriting of “Deathfugue” published a decade later:

Came, came.

Came a word, came,

came through the night,

wanted to shine, wanted to shine.

Ashes.

Ashes, ashes.

Night.

Night-and-night.—To

the eye, go, to the moist.

Celan’s desire to fracture conventional forms of sense-making gave much of his work a certain opacity: It resists attempts to directly apprehend its meaning, while opening itself up to readers willing to dwell in its strange shapes.

In the decades since Celan’s death by suicide in April of 1970, his poetry’s resonance has not abated. His enigmatic body of work—deeply situated in the post-Holocaust moment yet engaged with broader questions of rupture—has influenced artists from Doris Salcedo to Yoko Tawada to Claudia Rankine. Last year, the poet and translator Pierre Joris, who has been bringing Celan into English for decades, completed his work with the release of Memory Rose into Threshold Speech, which gathers together Celan’s early poetry collections, and Microliths They Are, Little Stones, which contains the poet’s previously unpublished prose. To honor the centennial and the release of Joris’s translations, we have curated a selection of Celan’s own works and a number of pieces in dialogue with him. Here you’ll find excerpts from Memory Rose and Microliths; etchings by Celan’s widow, the artist Gisèle Celan-Lestrange, made in conversation with his work; a series of brief meditations by the poets Aria Aber, Chase Berggrun, Peter Cole, and Michael Hofmann on mystery, translatability, and the limits of the speakable through readings of single Celan poems; a comic by Anne Carson in conversation with Celan’s “Todtnauberg”; and a discussion between Joris and the poet Fanny Howe on the work of ferrying Celan’s singular oeuvre from one language to another.

This online edition of the Celan folio also features a selection of poems by two underappreciated poets closely linked to Celan, translated and introduced by Carlie Hoffman: Rose Ausländer’s “To Life,” from which Celan inherited the image of black milk, and which was previously unavailable in English; and three poems by Selma Meerbaum-Eisinger, a younger cousin of Celan, who died at the age of 18 in a Nazi labor camp.