What the Popular History of the Soviet Jewry Movement Leaves Out

An interview with Tova Benjamin, the curator of the Jewish Currents Soviet Issue’s centerpiece section.

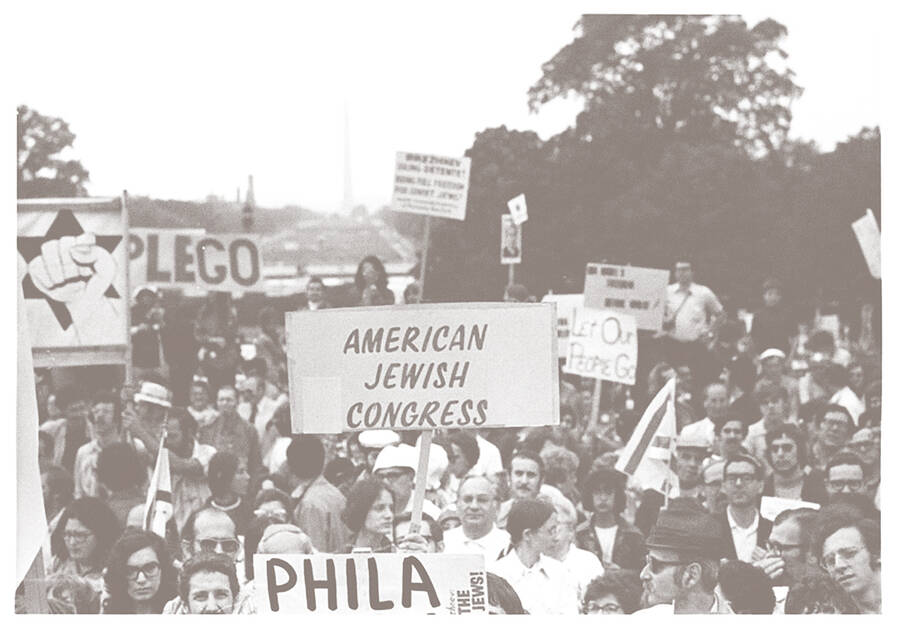

Freedom Assembly for Soviet Jews, Washington, DC, 1973

Over the course of this week, we’ve been making the centerpiece of the Jewish Currents Soviet Issue—a section comprehensively reconsidering the history of the Soviet Jewry movement—available online. The seven articles that make up the section can now be found here. The section grew out of what was originally supposed to be a single article pitched several years ago by Tova Benjamin, a PhD candidate studying Russian and Jewish history at NYU, but it grew into a much more elaborate and multifaceted exploration of a movement that spanned three decades and three countries.

For this week’s newsletter (subscribe here!), I called up Tova to ask her about how this section came about, what she learned in the process, and what she hopes readers will take away from it. Our conversation has been edited and condensed.

David Klion: What’s the origin story of the Soviet Jewry movement section?

Tova Benjamin: Five years ago, I took a class with my advisor at NYU, the historian Gennady Estraikh. Every year he teaches a class called “Israel, the United States, and the Soviet Union” where he looks at those three countries as a diplomatic triangle. And he devotes a good portion of the course to the postwar history of American Jews who were lobbying and building a grassroots activist movement for freedom of immigration and religious rights for Soviet Jews, and about how Jews in the Soviet Union came to reclaim or rediscover certain aspects of their Jewish identity, especially Zionism and the Hebrew language. He said that with the opening of the archives, historians have been able to see how activists successfully made Soviet Jewish emigration and religious freedom a big problem for American and Soviet officials. That really interested me, so I ended up writing a research paper on the topic. Because of my own background growing up Chabad and with these stories about Chabad in the Soviet Union, I was initially very interested in Chabad’s involvement in the Soviet Jewry movement. But gradually I became much more interested in the memory of the movement in general. I was reading all this stuff these Jewish organizations were publishing about this history, reminiscing about Jewish unity and human rights, and something felt off.

This wasn’t just a liberal human rights movement; it was an American movement in opposition to the Soviet Union happening during the Cold War. It was this massive movement, resulting in some of the largest and most concentrated Jewish political efforts from Jews in US history, but when the Soviet Union collapsed, the whole movement basically disappeared, just ended anticlimactically. After 1991, people started making these very outlandish claims about how the movement caused the Soviet Union to collapse, or helped end the Cold War. A lot of major figures in contemporary Jewish organizations came up through activism within the Soviet Jewry movement and developed very intense nostalgia for a time when, as they would put it, Jews all came together around this Jewish cause. This nostalgia feels like a reaction to Jews who oppose Israel’s occupation, contrasting this supposed unity over Soviet Jewry to today’s splits over Zionism.

There was a lot of writing in the early 2000s about how the Soviet Jewry movement grew out of Jewish involvement in the civil rights movement, when Jews felt alienated from Black freedom movements and were searching for a “Jewish cause,” but the more I looked into it, the more false that seemed. With the notable exception of Abraham Joshua Heschel and Glenn Richter, almost none of these activists came out of civil rights. In 2010, Gal Beckerman wrote When They Come For Us, We’ll Be Gone, which cemented a lot of these popular stories about how Jews in America rescued Soviet Jews and helped end the Cold War, and in many ways that was the last word on the movement for a while. In the past ten years, there has been almost no pushback on the accepted story about the movement that shaped our parents’ generation and helped form the inward-looking attitude of American Jewish institutions as we know them today. And I realized that there hadn’t been a popular retelling that wasn’t offering a triumphant story about Jews uniting over their identity across borders and successfully emigrating to Israel, which felt like a reflexively Zionist narrative. So about four years ago, I pitched a revisionist piece to Jewish Currents that would reframe the narrative of the Soviet Jewry movement in the US as an origin story for contemporary Jewish identity politics, because of the way American activists for Soviet Jewry crafted a Jewish culture of protest to push their cause.

DK: What was the journey from that initial pitch to the section that we ended up getting in the Soviet issue four years later?

TB: Initially, [JC Editor-in-Chief] Arielle Angel accepted the pitch. She was also very interested in the Jewish identity politics angle. So I tried writing a 3,000-word piece, and right away I realized it was very unwieldy: first of all, because it’s a 30-year history of a movement spread between three countries that involved many different organizations and individuals across the political and Jewish spectrum, and second, because I was trying to speak to multiple audiences. The audience needed to include people who participated and remember it triumphantly; an older generation of Jewish Currents readers, who would have opposed it as a nationalist and Zionist movement; and a younger generation who had barely—or maybe never—heard of it; as well as some people whose emigration or parent’s emigration was aided by these activist efforts. I was trying to revise the narrative of what the movement was and also introduce it at the same time, which became very difficult. The 3,000-word piece turned into a 6,000-word piece, and then we tried to cut it back down.

Eventually, Arielle called me and said we should actually make this a whole issue, with a special advisory board of artists and academics and people who have personal relationships to these histories. I had the task of curating a whole section where my original reframing of this history would serve as an introduction. I started rethinking what the section was going to be, because I realized we would have the space to tell the global story, as opposed to a mainly American story.

DK: How did you go about finding the specific contributors to the section and figuring out the specific topics they would be addressing?

TB: We wanted each piece to stand individually on its own, but we also wanted to collectively tell a story. I knew that Hadas Binyamini was working on the links between the Soviet Jewry movement and neoconservatism around the Jackson-Vanik Amendment, and she sent us a really great pitch about that. Jonathan Dekel-Chen pitched us something more general, but also mentioned he’d been doing this original research on Israel and its involvement in the movement so we helped him shape a piece that could fit. Olesya Shayduk-Immerman pitched us on something completely different than what we eventually ended up with; we found the angle for that piece in conversation with her. She ended up writing about the way these refusenik exile-to-exodus narratives themselves are made, and how asking different questions of Soviet emigrants produced surprising answers. With Anna Shternshis’s piece about Soviet antisemitism, we sought it out. We realized that we needed to address what was happening in the Soviet Union, or the section would fall apart. A lot of people in the US and Israel had altruistic intentions, but they were out of touch, sometimes to a laughable or offensive extent, with what was happening in the Soviet Union. Something I’m really happy about is that in the end, three of the seven pieces are about what was happening on the Soviet side: Olesya’s, Anna’s, and Emily Tamkin’s piece, which looks at those dissidents in the Soviet Union who weren’t celebrated by American Jewish activists to the same extent as refuseniks were, but who articulated another kind of Jewish future.

Anna’s was the last one we commissioned, and I think it ended up being the glue for the whole section. She really gets into the history of antisemitism in the Soviet Union, a history I don’t think a lot of American Jews really understand, and that is still contentious. A lot of today’s discussions about antisemitism on the left have their origins in assumptions about Communists, and especially Jews who joined the Communist Party. Anna’s work is based on hundreds of oral interviews, and she does a really good job of breaking down what was actually happening and balancing out these often bad faith debates. She shows that yes, there was a lot of anti-Jewish sentiment, but that wasn’t actually what motivated people to leave. Meanwhile, on the US side, we see people weaponizing Soviet antisemitism to such an extent it gets compared to the Holocaust, with some even describing it as a “spiritual genocide.”

We also had Larry Bush, the former editor of Jewish Currents, go through the archives to show how the magazine covered the movement at the time. Jewish Currents started out as kind of a Stalinist rag. After the murder of the Yiddish poets in 1952, they published some editorials trying to reckon with what they had previously ignored about Stalin and Soviet antisemitism. They continued publishing editorials throughout the Cold War years trying to grapple with how to oppose Soviet crimes without joining the Cold Warriors, who they saw as including fellow American Jews involved in the Soviet Jewry movement. I became really fascinated with these writings, and we picked a few of them out of the archives and asked Larry to read through them, reframe them, and introduce them for us. I think that’s really cool, both for older Jewish Currents readers who remember the movement, nostalgically or not, and for younger readers to see where Jewish Currents stood at the time and how the publication today relates to its own history.

DK: What did you learn that surprised you and that you didn’t know when you set out to do this?

TB: In Hadas’s piece about how Democratic hawks co-opted the Soviet Jewry movement, I was very surprised to learn about the grassroots support for neoconservatives. From her work, I understand that historians usually think of neocons as not really having a larger base. At the time the movement started, the legacy Jewish establishment organizations were less interested in particularist politics—that is, in supporting specifically Jewish causes. That was a push that came from activists on the ground.

I had also previously assumed that in Israel, these efforts were driven by clandestine intelligence services working behind the scenes, and not by a grassroots movement. Jonathan’s piece really surprised me, because he completely overturns that assumption. You actually find a similar story in all three countries, where activists start pushing Jewish communal leaders and their governments to invest in “Jewish issues.”

I also revised some of my own understandings of the movement, and began to see it as a bigger story about Jewish belonging in the long view of the 20th century, and how activists in the US and Israel were actually articulating competing visions of where a Jewish future could be, which ended up being the framing for the section.

DK: How has the section been received so far, and what impact are you hoping it will have?

TB: When Arielle and I were first developing my piece, the question of what it means to use your identity as a Jew in your organizing seemed really pertinent. A lot of people who study the movement say that American Jews were searching for a cause, and for a way to deal with guilt about the Holocaust, and that was funneled into the Soviet Jewry movement. I first started working on this when the Never Again movement was active, around when Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez referred to refugee camps on the Mexican border as “concentration camps.” There was a lot of anger from some Jewish establishment figures about her use of Holocaust comparisons, and a lot of Jewish organizers on the left felt that they could flip that on its head and use it themselves. What really interested me about the Never Again movement was how the protests were using Jewish religious rituals in a way that was very similar to the Soviet Jewry movement, with the difference being that it was less particularist and more universalist now.

With the Soviet Jewry movement, I wondered what made it so easy for anti-communists and neoconservatives to co-opt this issue and to fit it into their policy agendas? Does that delegitimize the movement, if you’re operating under a banner that a Jewish terrorist like Meir Kahane can join beneath as well? I hope readers can use this history of one of the most significant Jewish political organizing efforts in the US to think about organizing today. Who did this movement serve, and to what end?

In terms of responses to the issue, it’s been really nice to see academics who work on this respond positively, especially the many historians whose work the section builds upon; we had felt a little nervous because it’s revisionist, and it’s pushing back on a lot of these established narratives. But people are really excited to see something that’s rethinking a movement that they remember or participated in. Arielle’s mom considers herself very much a liberal Jew, and she was very involved in the movement and was really excited to read some of the pieces, especially the one about the Jackson-Vanik Amendment. She said something like, “we were just too naive to realize what was happening at the time.” I gave it to my grandma who read all the pieces, and told me that she walked away with a revised sense of a story she thought she knew. She said that reading the pieces made her want to stop donating to the AJC. That’s the outcome I’d like to see, for grandmas to stop donating to the AJC.

David Klion is a writer and a contributing editor at Jewish Currents.