Henry “Scoop” Jackson and the Jewish Cold Warriors

An alliance between Jewish activists and congressional neocons made Soviet Jewry a key issue in superpower relations—and reshaped American Jewish politics in the process.

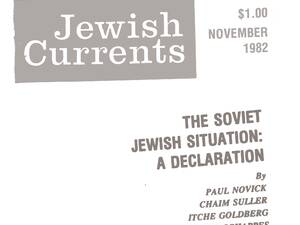

Sen. Henry “Scoop” Jackson visiting Soviet Jewish émigrés in Israel.

ON SEPTEMBER 26TH, 1972, 120 representatives of Jewish organizations—including envoys from local federations, community relations councils, and national groups like the American Jewish Committee and the Anti-Defamation League (ADL)—met at the tony Mayflower Hotel in Washington, DC, for an emergency summit. As members of the National Conference on Soviet Jewry (NCSJ), one of several umbrella organizations for groups in the growing American Jewish movement to support the emigration of Soviet Jews, they had gathered to discuss a new obstacle to their cause: a recently instituted Soviet diploma tax, which sought to slow the brain drain of highly educated Jews from the USSR by imposing prohibitive fees on university graduates who attempted to emigrate. The NCSJ members were determined to mount a response.

They had also agreed to hear from Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson, a hawkish Democrat and committed anti-Communist from Washington state. He wanted the NCSJ’s support for his proposed amendment to the East-West Trade Act, which would allow President Richard Nixon to waive restrictions on trade with communist countries as part of his efforts to defuse tensions with the Soviet Union, known as détente. With his amendment, Jackson proposed to limit the president’s ability to open trade with the USSR: To receive access to American credits and investment guarantees, the Soviet Union would first need to comply with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and liberalize its emigration policy, allowing Jews to leave freely. “The time has come to place our highest human values ahead of the trade dollar,” Jackson urged his audience at the Mayflower Hotel. “You know what you can do? I’ll give you some marching orders. Get behind my amendment. And let’s stand firm.” The audience responded with a standing ovation. Later that day, the NCSJ delegates voted unanimously to endorse the amendment.

Though Jackson pitched his amendment to the Jewish leaders as a humanitarian response to the diploma tax, his concern for human rights dovetailed with his fierce opposition to détente. The senator wanted to throw a wrench in the Strategic Arms Limitations Treaty (SALT I), which Nixon had signed in May 1972, an agreement intended to slow the arms race and limit the deployment of weapons. Nicknamed “the senator from Boeing” in reference to the defense industry headquartered in his home state, Jackson had material reasons to stand against the slowing of weapons development. He called SALT I a “bum deal” and compared Nixon’s negotiations with the Kremlin to World War II-era appeasement of the Nazis, arguing that the Soviet Union would only respond to threats and shows of force. His criticism of Nixon’s international machinations resonated with the spirit of congressional activism on foreign affairs which grew amid popular criticism of the Vietnam War and revelations of executive corruption.

With his amendment, Jackson also aimed to change the direction of the Democratic Party, in which New Left and anti-war sentiments were gaining influence. Jackson’s congressional office, which historian Justin Vaïsse has called a “nursery for neoconservatives,” was not only the nerve center of Democratic advocacy for American military superiority, it was also a stronghold of opposition to the critiques of American imperialism, racism, and capitalism then being advanced by university students, Black Power activists, and anti-war protesters at home, as well as anti-colonial movements around the world. “This society is not a guilty, imperialistic, and oppressive society,” Jackson said in 1971, defending America’s moral character in response to leftist critics. “This is not a sick society. This is a great country.” The liberal reformer George McGovern had beaten Jackson in the 1972 Democratic presidential primaries before himself suffering a devastating loss to Nixon. A budding coalition of intellectuals, Black liberals, trade unionists, disaffected Democrats, and foreign policy elites—later known as neoconservatives—saw McGovern’s defeat as proof that the Democratic Party needed to take a more conservative tack.

By early October 1972, Jackson’s amendment had won the backing of two more moderate senators—Jacob Javits (R-NY) and Abraham Ribicoff (D-CT), as well as that of Rep. Charles A. Vanik (D-OH), who had agreed to co-sponsor it in the House. Jackson and his staffers looked to the Jewish community as a powerful source of moral legitimacy and sought to include them in a coalition to back the legislation, alongside more reliable anti-détente partners like Eastern European immigrants, who opposed Soviet rule in their countries of origin, and labor’s AFL-CIO, then headed by the stridently anti-Communist George Meany, which tried to limit the onslaught of rising imports amid devastating job losses.

By the close of the decade, support for the Jackson-Vanik Amendment became “the moral and psychological equivalent of loyalty to the Jewish people,” Philip Baum of the American Jewish Congress said in a speech that was quoted in the Los Angeles Times in 1978, at times galvanizing even more popular engagement than support for Israel did in the same period. Before 1972, the Soviet Jewry movement’s achievements had largely been limited to popular protests and symbolic resolutions; Jackson, by contrast, presented Jewish leaders with an opportunity to make Soviet Jewry a key issue in superpower relations. Today, many activists remember the struggle for the amendment’s passage—and the broader movement for Soviet Jewry—as a rare period of American Jewish unity, when a spirit of “ahavas Israel,” or love of the Jewish people, triumphed over partisan and religious differences. The movement seemed to bring together every segment of American Jewry: modern Orthodox college students and counterculture activists, the Jewish Defense League and Habonim Dror, Miami housewives and members of the New York intelligentsia, Lubavitch Hasidim and Jewish socialists.

By the close of the decade, support for the Jackson-Vanik Amendment became “the moral and psychological equivalent of loyalty to the Jewish people,” Philip Baum of the American Jewish Congress said in a speech that was quoted in the Los Angeles Times in 1978.

But the appearance of unified support for the amendment emerged from a contentious communal power struggle. The two-and-a-half-year legislative battle to pass the amendment gave rise to a new generation of radical Jewish activists fed up with the sluggish pace and quiet diplomacy of Jewish institutional leaders and philanthropists, who wavered as both Jackson and Nixon attempted to court them. While the institutional leaders shared the Zionism and anti-Communist politics of the grassroots and wanted to support Soviet Jewry, they hoped to do so without dragging American Jews into Cold War superpower struggles. For the proud Jewish activists—angry at Jewish institutions for seemingly prioritizing the welfare of non-Jews over solidarity with their brethren overseas—no tactic was off the table in their urgent campaign to save Soviet Jews from spiritual annihilation. When grassroots activists partnered with Jackson’s team to triumph over legacy Jewish institutions, they pushed the Jewish community into an emerging hawkish Democratic coalition, turning Jews, as former Forward editor J.J. Goldberg has written, into “the poster children of a renewed Cold War.” In helping to pass the amendment, Goldberg explains, “the Jewish lobby, for years a central element in coalitions of the liberal left, now became an important factor on the national-security-minded right.”

THE FIGHT for Jackson-Vanik marked the political maturation of the US Soviet Jewry movement, but the movement itself extended far beyond Capitol Hill. Its greatest significance was arguably its effect on hundreds of thousands of American Jews—an army of “students and housewives,” in the words of the famous refusenik Natan Sharansky—who made the movement a force in Jewish life and American foreign policy for over two decades. Rabbi Avi Weiss, a leading Soviet Jewry activist and founder of the Open Orthodoxy movement, later argued that the much-publicized 1970 trials of a group of Soviet Jewish activists did more to unify American Jewry than Israel’s 1967 War.

The movement itself, however, was far from unified, incorporating both the “old guard” of American Jewish institutions and new grassroots groups like the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry (SSSJ) and the Union of Councils of Soviet Jewry (UCSJ). Whereas the former had been guided since the 1930s by the belief that they could best guarantee Jewish well-being by enshrining civil liberties and advocating for the rights of Black Americans, immigrants, and the poor, the latter rejected this universalist approach to Jewish welfare, arguing that Jews must rise up to ensure their own safety, whether in Brooklyn, Moscow, or Tel Aviv. While many of the longer-standing advocacy organizations treated Soviet human rights as only one of many competing priorities, the grassroots groups focused solely on the plight of Soviet Jews.

The grassroots activists’ goal was not only to change Soviet emigration policy, but to revolutionize American Jewish politics, pushing them toward a proud, muscular Jewish particularism. Just as Jackson’s neocons argued that mainstream Democrats were allowing anti-war and Third World liberation protesters to shame them for spreading democracy and fighting communism, Soviet Jewry activists criticized Jewish institutions like the Conference of Presidents or the Council of Jewish Federations for apologizing for Jews’ upward mobility and success, and failing to fight for specifically Jewish rights. Many activists were further motivated by what they saw as American Jewish leaders’ inaction in the face of the Nazi genocide of European Jewry. “The liberation of Soviet Jewry was my generation’s chance to undo American Jews’ silence during the Holocaust,” remembers journalist Yossi Klein Halevi, who was active with both SSSJ and the Jewish Defense League. “In saving Soviet Jewry, we would save ourselves.” Though Soviet Jewry activists had rejected most of the New Left’s thinking and resented its influence on American politics—from its criticisms of capitalism and state power to its calls for global solidarity between anti-colonial struggles—they mirrored other ’60s countercultural groups in opposing what they saw as the assimilation, conformity, and shallow materialism of their community’s mainstream. Activists, some of whom spent time in the civil rights and anti-war movements before becoming alienated by anti-Zionism and Black separatism, borrowed New Leftist language to refer to the institutional old guard as the “Jewish establishment,” and repurposed its protest tactics to demand that Jewish leaders use their access and contacts in Washington on behalf of Soviet Jews.

The grassroots activists’ goal was not only to change Soviet emigration policy, but to revolutionize American Jewish politics, pushing them toward a proud, muscular Jewish particularism.

Above: Members of BETAR, a revisionist Zionist youth movement, stage a sit-in at the Rockefeller Center offices of the Soviet news agency TASS in New York, February 18th, 1976.

Left: Young Jewish militants, including members of the Jewish Defense League, burn a Soviet flag during a demonstration in New York, September 8th, 1972.

Meanwhile, Nixon was also attempting to court the Jewish community: On April 19th, 1973, he invited 15 Jewish leaders to a meeting at the White House. Among them were major Republican donors such as Jacob Stein, chairman of the Conference of Presidents, and Detroit millionaire Max Fisher, former president of the Council of Jewish Federations. Nixon warned the Jewish leaders that Jackson’s aggressive tactics might backfire with Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev, resulting in further repression for Russian Jews. “You gentlemen have more faith in your senators than you do in me,” Nixon told them. “And that is a mistake. You’ll save more Jews my way. Protest all you want. The Kremlin won’t listen.”

In the wake of the meeting with Nixon, the Jewish leaders attempted to chart a middle course between the president on the one hand and Jackson and the grassroots organizations on the other. When the group—led by Fisher, Stein, and Charlotte Jacobson, chair of the American section of the World Zionist Organization—released a statement after the meeting thanking the president for his commitment to Soviet Jewry, they did not include an explicit endorsement of the Jackson-Vanik Amendment. Both the grassroots groups and the senator’s staff interpreted this silence as a sign that the Jewish establishment was wavering in its commitment to their cause.

In response to the statement, the congressional staffers pushing the amendment—including Vanik chief of staff Mark Talisman; Jackson staffer Richard Perle, the future ideological architect of the Iraq War; and Ribicoff aide Morris Amitay, who would later become the chairman of AIPAC—intensified their alliance with grassroots activists in SSSJ and UCSJ, as the scholar Paula Stern chronicles in her 1979 book Water’s Edge: Domestic Politics and the Making of American Foreign Policy. Perle complained to Halevi that the Jewish leaders had “melted like butter” in the meeting with Nixon. In comparison, the activists saw Jackson as a courageous voice for Jewish human rights: “One must thank G-d for the only Jewish leader left in America—Senator Jackson,” Halevi wrote in an editorial. The grassroots also activated their peers in the Soviet Union, calling on Jewish dissidents in Moscow to urge American Jewish leaders to stay the course. “Remember,” more than 100 Soviet activists wrote in an April 23rd letter, “your firmness and steadfastness are our only hope. Now as never before, our fate depends on you. Can you retreat at such a moment?”

Days later, when NCSJ and the Conference of Presidents met to discuss the amendment, only a small minority, led by Stein, still opposed issuing a statement in support. The vast majority of NCSJ member groups were firmly behind Jackson. When Stein moved to end the meeting before the assembly could consider a public declaration backing the amendment, a “clash bordering almost on insurrection” ensued, in the words of B’nai B’rith human rights activist William Korey, who wrote about the event in The American Jewish Year Book. The amendment’s supporters won, and on May 2nd, Stein, Fisher, and NCSJ founding chairman Richard Maass issued the clarifying statement that the grassroots had demanded, declaring their support for Jackson-Vanik.

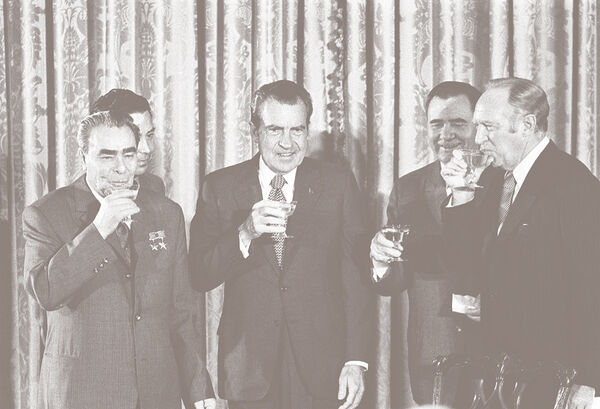

President Richard Nixon with (from left to right): Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev, Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs Andrei Gromyko, and Secretary of State William P. Rogers, June 19th 1973.

Ill feelings between Jewish activists and communal leaders continued to simmer, since the latter remained caught between Jackson and Nixon. “We must adopt a dual line of support for (the Jackson Amendment) without undermining the President’s efforts for détente,” Jacobson told JTA in July. A Miami Beach rabbi likewise insisted in another JTA bulletin: “We are not here as cold warriors, we are not here to do battle with the Soviet Union or Mr. Brezhnev. We are for détente. But should détente be built on the agony of Soviet Jews?” In fall 1973, the outbreak of the October War (also called the Yom Kippur War) between Israel and a coalition of Arab states only increased the pressure on Jewish leaders. They found themselves called into a meeting with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, who warned them that Brezhnev’s frustration over Jackson-Vanik might imperil Soviet support for an Israeli–Arab cease-fire. According to Stern, Jackson castigated the Jewish leaders when he heard about the meeting: “The administration is always using you.” He also reminded them of his lockstep alliance with the grassroots groups. If they backed away from the amendment, “I’ll go back to your people and tell them,” he warned. The coalition behind the amendment held firm.

THE AMENDMENT PASSED both houses of Congress with overwhelming bipartisan support on December 20th, 1974, months after Nixon’s resignation removed its biggest stumbling block. To this day, supporters argue that it opened the gates of the Soviet Union to Jewish emigration, pointing to surges in 1973, 1978–1979, and throughout the ’90s as proof of its effectiveness. But historian Geoffrey Levin and others have argued that the amendment itself ultimately exerted little force on Soviet emigration policy, which reflected the ever-evolving US–Soviet relationship more than a straightforward response to American economic pressure.

For neocon icon Elliot Abrams, a onetime staffer for Jackson who worked on national security in multiple Republican administrations, the political lesson of the Soviet Jewry movement is that “there is simply no substitute for power and the unashamed willingness to use it.”

Regardless of its efficacy, the passage of Jackson-Vanik certainly constituted a triumph for the new class of Jewish activists, who believed that American Jews should unabashedly use their power to advocate in their own self-interest. In fighting for the amendment, Jewish particularists had linked the survival of world Jewry to the success of American anti-Communist ventures. Through their alliance with congressional neocons, justifications for American military supremacy and Jewish ethnic pride fed into and inspired each other. “That victory that we scored was a macho trip for the Jewish community,” Philip Baum of the American Jewish Congress, one of the few critics of the amendment, would say later. Indeed, for neocon icon Elliot Abrams, a onetime staffer for Jackson who worked on national security in multiple Republican administrations, the political lesson of the Soviet Jewry movement is that “there is simply no substitute for power and the unashamed willingness to use it.” By allying with Jackson Democrats over Nixon, grassroots activists attached American Jewry to a burgeoning coalition that would come more fully to power with the rise of the Reagan administration. In the ensuing decades, Jackson’s neoconservative successors would gain increasing influence over foreign affairs, exporting what they saw as American virtue around the world through interventionist foreign policy and the promotion of military supremacy.

In 1974, the leadership of the “establishment” Conference of Presidents and NCSJ turned over to executives who were much friendlier to the hardline positions of Jackson and the grassroots. The ascent of these new leaders was representative of the new era that the fight over the amendment had ushered in. The Zionist, anti-Communist grassroots who had allied with Jackson had become the prevailing force in Jewish communal politics.

Hadas Binyamini is a PhD student in history and Hebrew and Judaic studies at New York University.