Faces of Flight

Ukrainian refugees in Israel cannot be reduced to any single narrative.

Since Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine on February 24th, over 30,000 Ukrainians have arrived in Israel—around two-thirds of whom are not considered Jewish and thus not eligible to immigrate under the Law of Return—along with at least 40,000 Russians, many of whom are fleeing political repression and Western sanctions. The sudden influx of refugees from both countries resists generalization: It includes people with documented Jewish ancestry and people without; people who had already been considering moving abroad in search of better opportunities and people who have left only out of necessity and who hope to someday return; people who believe passionately in Israel as a Jewish homeland and people who feel no investment in it or actively criticize it. Some are patriotic Ukrainians, some are patriotic Russians, and some are neither. Some will become Israeli citizens, some will remain in the country under murkier legal circumstances, and some will eventually leave, by choice or not. Some are already finding homes in illegal Israeli settlements in the occupied West Bank.

This spring, we asked the Soviet-born artist Anna Lukashevsky to interview and create portraits of Ukrainian refugees who arrived in Israel this year; she also ended up interviewing a Russian dissident who recently fled. Lukashevsky herself left post-Soviet Lithuania for Israel in 1997 in search of greater economic stability, living precariously first on a kibbutz and then in Jerusalem, where she studied art and design at Bezalel Academy. In many ways, she told Jewish Currents, she was “disappointed” in Israel, frightened of “wars, apartheid, and wild capitalism”; nonetheless, 25 years later, she finds herself at home in Haifa, where much of her current work draws from chance encounters with strangers in the neighborhood around her studio. Types, her recent solo show at the Haifa Museum of Art, collects these portraits, focused on characters who simultaneously inhabit and transcend their social and ethnic identifiers. When she meets someone interesting, she sketches them on the spot and then invites them to her studio for a series of sessions in which she paints them while learning about their lives.

For this project, Lukashevsky met with her interview subjects—friends of friends, community members, people who responded to Facebook posts—at cafes, painting their portraits in acrylic on paper as she recorded conversations with them in Russian. They spoke about life in Ukraine before and after the invasion, and about escaping military terror for the uncertainty of emigration. She heard repeatedly about the state’s difficulty in providing for the new arrivals: “My impression is that people get help from other people and not from the state,” she said.

As these excerpted conversations with seven recent immigrants attest, there is no single interpretation of their stories. Contributors to our Soviet issue wrote earlier this year about how the individual stories of Soviet Jewish refugees to Israel and North America have often been distorted, simplified, and weaponized on behalf of nationalist agendas; historians have sometimes struggled to recover the story of the individual from underneath a solid, convenient communal account. We wanted to hear from people directly in the moment before they are recruited into such tidy narratives, to understand what the war in Ukraine has meant to those whose lives have been thoroughly disrupted by it.

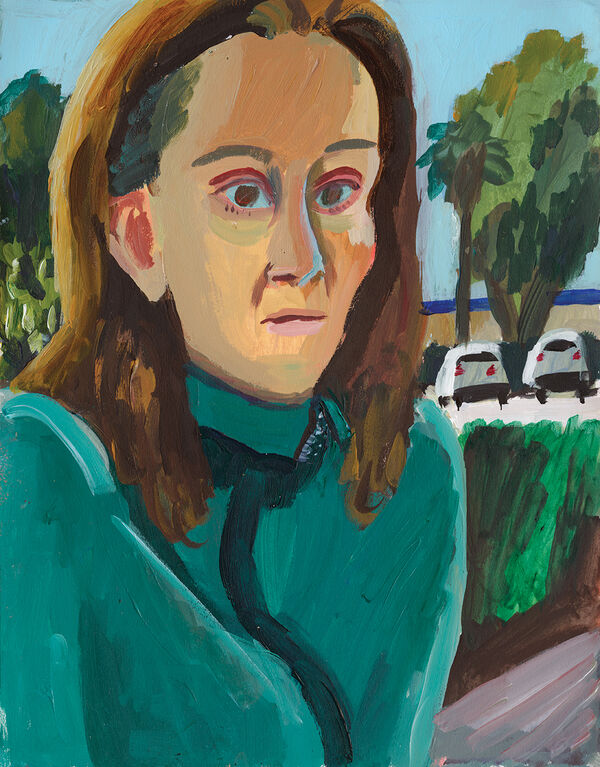

Olga Susha, 33, Irpin

Statistically, Irpin has suffered more than anywhere in Ukraine, with the fewest buildings left standing. We repatriated[1] before, a long time ago. Now it turns out we’re considered returnees, which means we have the right to work, but we don’t get any help as refugees—none. There are a lot of people here volunteering to help us. That’s how we have a couch for my mother-in-law; there’s nowhere else to put her. I came with my daughter, and then two weeks later my husband was able to get out thanks to the Israeli consul. We also got help from volunteers in Ukraine and in Poland. Here, the state does not help in any way. People help us.

We first went back to Ukraine because we couldn’t find a job to our liking here. We were only offered cleaning jobs, or jobs in factories, and when the baby came, I couldn’t work factory shifts. Even though everyone has a higher education, they could only work in construction. It’s clear that our education is not particularly valued. We basically know Hebrew, and we can study to brush up, but when you say you’ve only been in the country for a year, that’s all anybody hears. So you’re only allowed to do hard, low-paying work. My husband worked on the construction site. It’s very dangerous, and he isn’t paid enough in proportion to the risk he faces. Now I’m planning to go to nursing school.

Are Jews the occupiers, like the Russians? The Jews drove the Arabs out, they were the ones who lived here originally . . . Well, it depends on when you start counting. No, I can’t say anything at all. It’s not my place yet. I’m a newcomer in any case. I don’t feel like I . . . I mean, how am I supposed to feel? Maybe living here will suit me, but I still can’t insist that this is my land.

Even if I stay here, I wasn’t born here, I don’t have roots or anything. You know, if your grandfather or great-grandfather were born here, you can consider this land your land. It’s not like that here for me. I’ll never be able to consider it that way.

The Zosimov family (pictured: Nadezhda Zosimova, 84), Mariupol

We are Ukrainian by nationality, but Mariupol is a Russian-speaking city. There was a referendum in Mariupol, and at the time, the city voted to secede and join the Donetsk People’s Republic[2], but our volunteer battalions recaptured the city and it remained part of Ukraine. The result is that Ukraine considers us separatists and the DPR considers us traitors. And so Mariupol has simply been ground into dust. At one point we were bombed very heavily. We were sheltering in the basement, and at that moment we hated both sides equally, because Ukraine could not protect us and Russia was bombing us. We didn’t even know for sure who was shooting at us.

We had an acquaintance who wanted to join the Azov Battalion[3] when the invasion started. He wanted to see action, and they wouldn’t take him, because they said people from Mariupol are all separatists. But he wanted to defend Ukraine; of course we all want our country to defend its borders.

The city is completely destroyed. Even if they were to rebuild it, all of our nine-story buildings are completely burned, and the concrete is deformed. The upper floors suffered the most, because they were bombed from the air. Everything has to be demolished and rebuilt—all communications, electricity, gas.

We knew we had to leave—by March 3rd, we were already being heavily shelled—but there was no way out. Our parents’ home burned down. Everyone was in the basement when the third floor was bombed and the fire started. Our neighbors in the building across the street let us stay overnight in their entranceway. Some of us stayed in a hospital that everyone who could had escaped to. A lot of people were wounded, and the conditions were horribly unsanitary. We had to escape the city under bombardment, in a car with a broken windshield.

There’s nothing to return to in Mariupol. Of course we love Ukraine and we’d like to go back to our native land. We don’t have any connection to Jewishness.

Marina Storozhenko, 40, Kharkiv

I came here with two children—one who just turned five after we left, and one who will be 15 soon. My friends here took us in; they insisted we leave Ukraine, and so did my husband, who said he would feel better if we did. But I worry about my other relatives; my mother stayed in Kharkiv with her sister. Our escape happened very abruptly, during diplomatic negotiations, when it became clear to my husband that there wasn’t going to be a resolution. An acquaintance of mine already had some extra train tickets. I didn’t feel ready to leave at all, but I left.

Before, we decided to hide in our cellar instead of going to the metro, so our kid wouldn’t experience the stress, so he would be at home. We would talk about it in a playful way, like we were just hiding from loud noises. I’ve been reading up on all the psychology about what you’re supposed to tell your kids. When we got here and there was a thunderstorm one time, I had to explain that these loud noises were from the rain, and the ones we had heard before were from a war. I had to explain that Dad stayed behind to defend our home from this war. And what’s a war? It’s when the soldiers of one country attack the soldiers of another. I said they’re not here to attack your dad, they’re just fighting each other over the territory where we live.

We took the train to Poland first, and from there we went to Israel. We don’t have savings, so I’m totally dependent on my friends. That’s the most uncomfortable thing for me. They wrote a letter; Israel doesn’t let just anyone in. We aren’t refugees, we’re tourists from Ukraine! I liked how it sounded when Israel declared us to be travelers, so that’s what I say we are. My sons are going to school here now on top of their online schooling from Ukraine, because if this drags on for a long time, at least they’ll make friends. Their school teaches in Hebrew, of course, but socially, we’re friends with Russian-speakers. The younger one has learned some songs and some Jewish customs. He even made matzah there one day.

Before all this, I didn’t realize I was such a patriot. If I went back, I would probably join the army. I might try to learn how to shoot. It’s not about killing, it’s about protecting one’s own home. Like if I were called to defend this coffee shop in Israel right now, that would be a call to action—to defend, precisely to defend, not to kill. Of course, world peace, I’m for that. I want good to triumph.

Julia Goldinova, 39, Kremenchug

We’ve wanted to leave Ukraine and go somewhere else for years. Last summer we found out my husband’s aunt had moved here in the late 1990s—well, we knew, but we never talked about the fact that my husband is Jewish on his grandfather’s side. Someone suggested that we could move to Israel because of his roots, and we started looking into what it would mean in terms of work and the children. By December we had decided to do it, but we procrastinated filling out the forms until January, and then we had follow-up appointments in mid-February when there was already talk of war. I got a visa, but the kids didn’t. My husband’s grandmother was also Jewish, but she hid it and there are no documents, so halachically we couldn’t prove our kids are third-generation Jews, and they don’t give visas to the fourth generation. My husband isn’t here because Ukraine didn’t let him leave.

We weren’t happy in Ukraine because there was no real movement toward democratic development. It may seem like a free country, but everything is connected to the oligarchs, everything is corrupt, and it’s impossible to fix even basic social issues. My husband is 41 and I’m 39, so we’re used to it, but objectively this is a country where the courts, the education system, and the healthcare system all depend on how much money you have. Kyiv’s infrastructure may be more developed than Kremenchug’s, but still, if you’re suing someone who drives a Lexus and you drive a Zhiguli, you’ll never win. You can’t afford to see a good doctor at a private clinic. Our kindergartens are traumatizing. They’re better here. The local kindergarten here in Israel announced that it would accept refugees, since we’re registered with the Ministry of Education. I also have ulpan[4] classes until September; I need to learn Hebrew. It’s not good to just sit around living off state assistance.

My husband’s aunt likes it here. Israel is her place now. She gave birth to her second daughter here, and the older one was six when she arrived. The girls are Israelis, and they speak Russian with accents—for them, Russian feels like a distant language. I don’t feel like a stranger here, even though I’m not Jewish.

The Russians say Ukraine has a problem with nationalists. It’s ridiculous—during the Maidan uprising I was probably a nationalist! What fucking nationalists? It’s just us, Ukrainians, the emotional Ukrainians with our inner lives. What they’re calling “nationalism” is just the upholding of one’s own roots, faith, culture, past, and history. Putin thinks that Ukrainians are just confused Russians, just poor wretches facing this incomprehensible Ukrainian nationalism, and that it’s fascism and needs to be purged. But really he just wants the nation not to exist, and it does exist.

I don’t understand why the Russians here in Israel can’t apologize to us. There’s one Russian guy in ulpan with us named Dima, and there are four of us from Ukraine, and we could see he was anxious. He’s Jewish, so I kind of get it; he also just used the way out he had available. He said he didn’t want any of this, and that he has friends in Russia who say we’re all Nazis and fascists. He tries to tell them it’s not true but they don’t believe him. They simply hate Ukrainians.

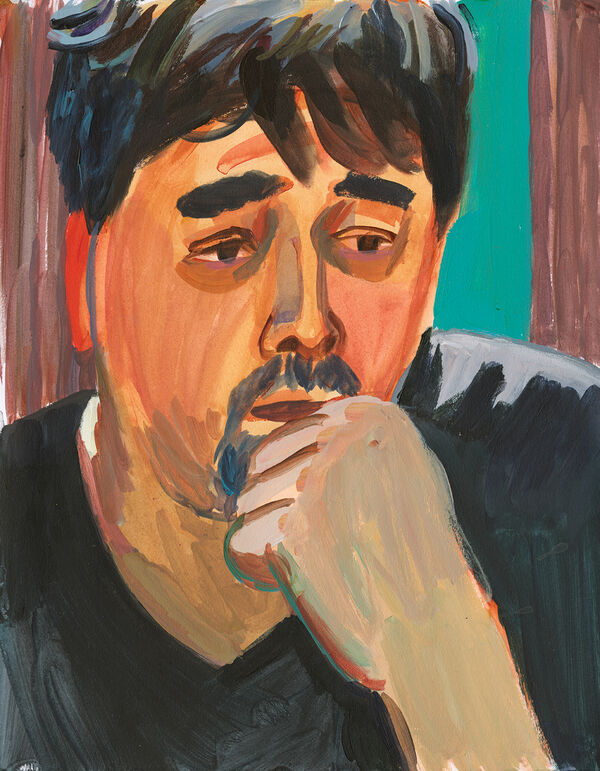

Dmitry Chernyshev, 56, Moscow

I worked as a creative director in an advertising agency for 15 years, and I had no interest in politics. I have four kids; what is there to do but earn money? Eventually I left advertising and wrote a book about how people come up with ideas, which I developed into a university course on creative thinking for the Higher School of Economics, and I became a top writer and blogger on LiveJournal, with tens of thousands of readers a day. I went to rallies against Putin starting in 2012, but the key turning point for me was when Russia annexed Crimea in 2014. My compatriots were rejoicing, but I wrote an article about how fascism had come to Russia. I resolved never to go to Crimea, even though it’s one of my favorite places, because it was stolen. I started an anti-Putin campaign and lost a lot of friends. I predicted there would be a bigger war and that Russia would be a pariah.

Over the next few years I blogged about Putin’s links to organized crime, drugs, and gangsters. I got banned from some social networks. I went to welcome Alexei Navalny[5] at the airport after he was poisoned, and I was at a rally for him during his hunger strike in prison. Even though it was a peaceful rally—people never burn cars or break windows at these protests—the police came to my home afterwards and said I had to come with them and that if I refused they would use force. I was fingerprinted, photographed, and put behind bars in a detention center for 15 days, which was three times longer than a guy I met in there who was arrested for heroin. When I got out I resumed my activism.

On February 24th, when the war began, I sat at my computer all day writing anti-war posts. The next morning, the police came to arrest me, but I wasn’t at home. They tracked me down while I was out, either through facial recognition or by following my phone. Then the FSB[6] interrogated me for hours. I invoked my constitutional right to remain silent. They wanted me to swear personal allegiance to Vladimir Putin. They threatened me with a new law that could have put me in prison for 15 years, but I pointed out that the law hadn’t been signed yet, and they couldn’t apply it retroactively. But then they started threatening my children’s future. So I agreed to sign a document pledging to end my online activities, and they let me go. We decided we had to leave the country—I wasn’t actually about to shut up, was I? But tickets were incredibly expensive, so we had to start selling our belongings. We bought tickets to Istanbul on Turkish Airlines, and then they canceled their flights and didn’t refund our tickets. We were only able to get out because friends in Tel Aviv bought us tickets.

Even then, I wasn’t sure whether they would let me out or not. In the few days of forced silence before the flight, I was preparing myself to go into hiding and keep working digitally, organizing a resistance movement. The people had to be called to an armed uprising. Now, people in Russia can’t do that, but I can do it from here.

I’m Russian, but my wife and daughter are Jewish. They got their Israeli passports after 2014, and they’ve lived here a little bit before. Now that we’re all in Israel, I’m trying to get citizenship, and we’ve rented an apartment for a year. I think Israel is more like Ukraine than like Russia—I mean that Israel is an outpost of Western civilization that is surrounded by Arab countries that are, let’s say, not the friendliest. But Israel takes hit after hit on Europe’s behalf, just like Ukraine does standing heroically between NATO and Mordor (that is, Russia). There are problems that have no solution—although as a humanist, I’m naturally in favor of a peaceful solution.

Israel is very afraid of quarreling with Putin, because he’s the first Russian president you could almost call an Israeli, right? But also Lebanon and Syria depend on him, and he could do a lot of nasty things to Israel. I’m sure many Israelis, like many Europeans, think the war in Ukraine might as well be in Uganda. But people will remember that Israel could have come to the aid of Ukraine and didn’t. That’s something that really frustrates me about Israel.

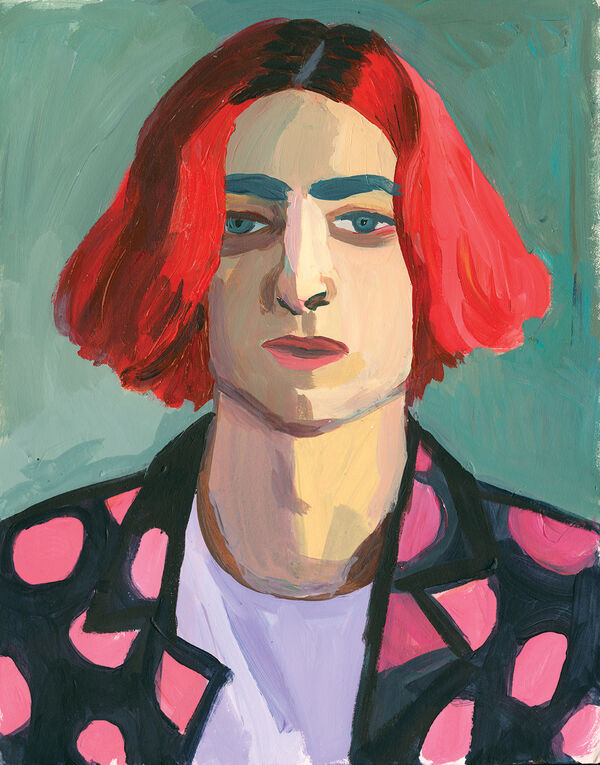

Daniel Rosenzveig, 17, Odessa

We went to Poland at the end of February right when the war started, and to Israel in early March. It was a spontaneous decision. My sister is already repatriated but I can’t yet because I’m not 18, plus I want to do one of Masa’s[7] programs, and I won’t be able to once I repatriate. These programs are a good way to take four months or so and learn Hebrew with other guys your age. Thank god I don’t have a girlfriend; a friend of mine has a boyfriend overseas and it’s really hard for her. I wasn’t in a hurry to leave my home country at first, but now that I’ve had to, I have no regrets. I’ve started to build up some distance from my parents and to live on my own. What’s happening is a tragedy for the country, but for my life it’s more complicated. Sometimes I get depressed and begin to miss my friends, but there’s no point in going back, it will never be the same as it was before, and I’d just be dependent on my parents. I’m quitting university because I want to live here.

I don’t want to join the army; I didn’t run away from Ukraine to build Israel. I’m not a patriot or a very political person in general. I support my country but I’m not cut out for war. There are untrained people just taking up arms and passing out during a firefight; what’s the point? My dad is in the age range for conscription, so he can’t leave, and my mom won’t leave without him. Although he does have a disability, so he could try to use that, and he’s Jewish, so he could fill out the paperwork to move here. But he doesn’t want to; he’s never been to Israel before. I was the only one they wanted to send here. Even if Putin wins, they’ll stay.

Even though I don’t speak Hebrew yet, I’ve been able to make friends here because I speak English. I’m not just sitting around at home getting bored here; I go out to bars, I have a part-time job. I want to work in a bakery or somewhere and rent my own place with friends. If I can get state support both as a refugee and as a repatriant, I’ll have some extra time to make it happen.

I feel safer in Tel Aviv than I did in Ukraine or Poland or in smaller Israeli towns where people might look at me strangely because of my long hair and how it’s colored. This is one of the most expensive cities in the world; my parents are sending me some money for rent. But it’s a beautiful, modern city full of creative people. What I don’t like about Israel is the imposed religiosity, like how all the bakeries are closed for Passover. Ukraine and Russia aren’t the same with Christianity.

Aliona Ihnatieva, 32, Kyiv

I worked as a TV director for ten years, working on talk shows focused on addressing social problems in Ukraine, like helping children get medical treatment. Ten years ago my husband Sasha and I actually thought about moving to Israel since he’s Jewish on his father’s side, but we were afraid, and then he got a good job and our daughter was born so we settled down. We woke up on February 24th and realized the Russians were attacking, and we had to hide in the basement of our building. But we couldn’t stay there long; it was hard to sleep, and to breathe. The children would scream at night. We should have left immediately for western Ukraine. Our friend Natasha called us from Israel and told us to come there. Driving to western Ukraine took a long time; there were checkpoints and traffic jams. When we arrived, it was dissonant seeing people out at cafes and having normal lives. I’m still in a traumatized state. Sasha stayed in Lviv to keep covering the war for TV, and I went to Tel Aviv. I hope he comes down here; his parents are here already, and it may not stay safe there.

I haven’t encountered nationalists in Ukraine, it’s not a real problem. But the Russians are forcing people in cities like Mariupol to sign papers saying they want to live in Russia. In Kyiv, lots of people speak Russian, although they’ve been switching to Ukrainian over the years. Russian is my native language, and no one was persecuted for speaking it, but at the same time, it was like, when you live in Ukraine, speak Ukrainian. It’s sometimes hard for me, and for our daughter to speak both; we speak 50-50 in Russian and Ukrainian.

I’m going to look for a job, but it’s hard because I don’t speak Hebrew. I was given a small amount of money on arrival. The priority is ulpan now; I’m not going to work for the next six months, because the most important thing is for me to study Hebrew.

I was afraid to come here because I understood that there are a lot of Russians here. I know that there are good people here who are against the war. But when we arrived in Israel and were waiting to get our documents processed, another plane arrived from Russia. Initially we were welcomed in Israel with flowers and toys and food and the Ukrainian flag. But when the Russians came in, conflict broke out. Some of the Russians who left Russia still get their point of view from Russian state television and support the Russian position. They were making these disgusting threats. Some of us were provocative too; somebody started playing the Ukrainian anthem. After you’ve lost your home, your loved ones, it’s hard to hold back your emotions.

The verb “repatriirovatsia” (“to repatriate”) and the noun “repatriatsiia” (“repatriation”) are the most widely used terms in Russian for Jewish immigration to Israel under the Law of Return. Though the Hebrew term aliyah refers to the same process, repatriatsiia does not share that word’s literal meaning of elevation or rising, only its implication of returning to a homeland.

The Donetsk People’s Republic is one of two Russian-backed separatist states in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine, along with the Luhansk People’s Republic.

A militia organized in the Donbas region in 2014 to fight Russian-backed separatists and subsequently incorporated into the Ukrainian National Guard as the Azov Regiment. Azov includes many far-right and neo-Nazi members and often employs Nazi iconography; although its membership is small and mostly Russian-speaking, Russia has used its existence to justify the invasion of Ukraine in the name of “denazification.”

A state-sponsored course of study for adult immigrants to Israel to learn Hebrew language skills.

A leading Russian opposition figure who survived a near-fatal poisoning attempt in 2020 and left the country for medical treatment; upon his return to Russia in early 2021, he was arrested and convicted on dubious charges of corruption and embezzlement, and remains in prison today.

Federalnaya Sluzhba Bezopasnosti, or Federal Security Service—Russia’s main intelligence agency, the successor to the Soviet KGB.

Masa Israel Journey is an Israeli state- and nonprofit-run organization that administers education, professional development, and travel programs in Israel for young Jewish people in the diaspora.

Anna Lukashevsky was born in Lithuania and emigrated to Israel in 1997. She has had solo shows at the Haifa Museum of Art, the Bat Yam Museum of Art, and the Rosenfeld Gallery. She is a member of the New Barbizon Group, a post-Soviet women’s artist collective.

David Klion is a writer and a contributing editor at Jewish Currents.

Hilah Kohen is a translator, editor, and literary scholar focused on relationships between nationalism and language choice. Her recent collaborations in Juhuri (Kavkazi Jewish) language advocacy appear in Russian Language Journal and on Bahador Alast’s YouTube channel.