The Ambivalent Émigrés

Antisemitism was a fact of life for Soviet Jews, but it did not top their list of reasons to leave.

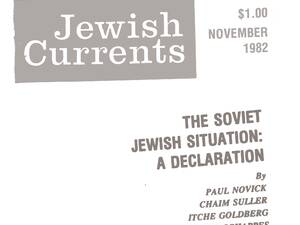

An elderly woman guards luggage at a train station in Austria, 1989.

LIZA R. knew how to take antisemitism in stride. It was the 1970s, and she had invited friends over for dinner to celebrate a recent promotion won by her husband, a construction engineer. She had prepared her signature dish, osek fleysh (sweet and sour meat), the way her mother used to, along with varenikes with cherries for dessert. At one point, one of the wives came into the kitchen and offered to help. “I love it when you cook this Jewish osek fleysh, and my husband likes when you cook those varenikes,” the woman said. But later, when Liza ran into the woman, who was also her colleague, at the office where they worked together, she said, “I’m so tired of you Jews. When are you going to Israel?” And as casually as she might have asked what made the osek fleysh so tasty, she demanded, “Give me gold, I need new teeth,” insisting, “You Jews always have gold.”

The woman had visited Liza many times and had often made such remarks, as Liza told me when I interviewed her for my book, When Sonia Met Boris: An Oral History of Jewish Life under Stalin. “Why did you keep inviting her over?” I asked, startled that she would tolerate such bigotry. “If I had been so sensitive,” Liza said, “I would never have had any friends!”

As it happened, at the time that Liza’s acquaintance suggested “going to Israel” as a natural next step for Jews in the Soviet Union, Jewish communities in the United States and Israel were engaged in a campaign pushing similar aims. The “Save Soviet Jewry” movement, which picked up steam in the late 1960s and lasted for more than two decades, intended to “rescue” Jews like Liza and her family from discrimination. American activists insisted on the urgency of their work, casting the state’s antisemitic policies as an existential threat. “We who condemn silence and inaction during the Nazi Holocaust, dare we keep silent now?” demanded Jacob Birnbaum, founder of the grassroots group Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry, in 1964.

And yet, antisemitism did not top the list of most émigrés’ reasons to leave. Liza and her husband themselves emigrated to the US only in 1990, soon after the Soviet borders opened. Her motivations: unstable economic conditions, environmental concerns due to the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant explosion, and, above all, the fact that her adult children had decided to pursue economic and social opportunities in America. It was only upon her arrival in the US that Liza learned that American Jews had narrativized her life in the Soviet Union as a story of oppression and persecution, and had cast themselves as the liberating heroes.

It was only upon her arrival in the US that Liza learned that American Jews had narrativized her life in the Soviet Union as a story of oppression and persecution, and had cast themselves as the liberating heroes.

Though the narrative wasn’t entirely “hers,” Liza didn’t mind framing her story that way. She had experienced plenty of bigotry, discrimination, and harassment because she was born Jewish. Besides, in American culture, immigration because of persecution was perceived as noble (e.g., Cubans fleeing Communism), while economic immigration was seen as suspicious (e.g., Haitians fleeing poverty). Most Jews who left the Soviet Union had lived there quite comfortably—though they were not wealthy by Western standards, they were by no means poor—so it was altogether easier to publicly adopt a narrative of “fleeing antisemitism” than to impart the complicated calculus that went into assessing their opportunities.

That the “religious persecution” immigration narrative was beneficial for both Soviet Jewish immigrants and Jewish relief organizations does not mean that instances of antisemitism were exaggerated, nor that Russian Jews were somehow less sensitive to its harms. But the American Jewish community’s act of projection still created a durable set of misunderstandings between the émigrés and those who received them. It obscured the reality of Soviet Jewish life, leaving Russian Jews feeling invisible to their new communities. In failing to accommodate the new arrivals’ relationship to their own Jewishness, which was often staunchly secular in nature, the narrative also upheld American Jewish institutions’ existing understanding of Jewish identity, which privileged religious expression over other types of participation. It also supported a myopic institutional focus on antisemitism as the most important lens through which to understand Jewish experience around the world.

IT IS PERHAPS EMBLEMATIC of the nature of Soviet antisemitism that there is no polite or neutral way to say “Jew” or “Jewish” in Russian. Today, even the officially accepted term, “evrei,” can still sound mocking or dismissive. That term replaced the commonly derogatory word “zhid” (“Jew” in Polish) at the beginning of the 20th century in a government-led attempt to soften unfavorable attitudes toward Jewish people, which early Soviet leaders, especially Vladimir Lenin, believed were exploited by Tsarist Russia to distract workers from the injustice of their conditions. Between 1927 and 1930, to encourage such a transition, the Soviet government invested significant resources in public education campaigns against anti-Jewish bigotry. Mass media publications, educational plays, mandatory public lectures at the workplace—all were designed to demystify Jews and prevent violence against them.

The public reaction to such efforts, however, was mostly hostile. Soon after the two Russian Revolutions of 1917—which overthrew the imperial government and elevated the Bolshevik party to power—the restrictions that had confined Jews to the Pale of Settlement were lifted. Suddenly, Jews seemed to many to be “everywhere,” especially in large cities like Moscow, Leningrad, and Kyiv, as well as within institutions of higher education. By 1926, according to demographer Vyacheslav Konstantinov, 15% of all students in the Soviet Union were Jews, though they constituted less than 2% of the population. Jews took positions in government offices, hospitals, and research institutions, and worked on high-profile construction projects, including the famous Moscow subway. It became almost commonplace to talk about the overrepresentation of Jews in the higher echelons of the new Soviet regime, with Leon Trotsky and other “old Bolsheviks” from Jewish families who now occupied positions of power cited as evidence. None of these individuals were connected to any Jewish community, but that didn’t seem to matter. The perception that Jews wielded significant power in the Soviet Union remained. Worse, Jews were commonly believed to be overrepresented in the Soviet punitive organs. They were seen as a force behind the expropriation of private property from peasants, known as collectivization, which led to widespread starvation in Ukraine; Stalin’s mass arrests of 1937–1939, known as the Great Terror; and the creation of the Gulag. Of course, Jews, too, starved during the Great Famine in Ukraine. And they, too, ended up in Gulags—mostly on flimsy pretenses—in the same proportions as their non-Jewish neighbors. Still, the perception that “Jews were not arrested” prevailed.

Astonishingly, during World War II, the attitude that “Jews have it better” persisted and even intensified. After June 22nd, 1941, when Germany invaded the Soviet Union, German mobile squad units began the systematic killing of Jews living in Ukraine, the Baltic states, Belarus, and Russia. By the end of 1944, about 2.5 million Jews had been murdered within 1941 Soviet borders. Reports of the Holocaust appeared in the Soviet press, but so did reports of the successful evacuation of Jews from the war zone into the Soviet Rear. Rumors began to spread that Jews were sitting out the war in Tashkent (“fighting on the Tashkent front,” as the cruel joke put it), while non-Jews were spilling blood on the Jews’ behalf. The fact that 440,000 Jews served in the Red Army did nothing to dispel the resentment.

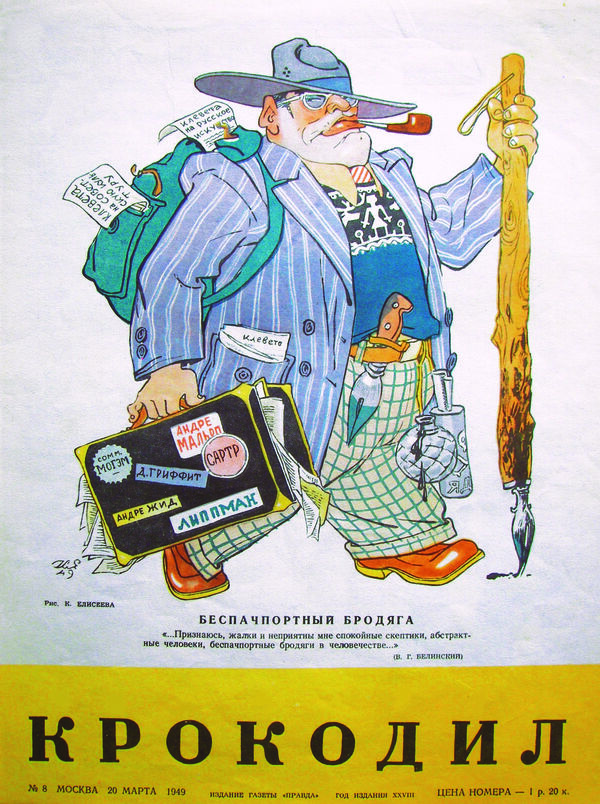

After the war, official policies toward Jews began to pick up on popular hostility. Anti-Western campaigns, animated by calls to expose unpatriotic “cosmopolitans” (often a code word for “Jews”), poisoned the lives of people already damaged by the war. All Jewish public organizations, including the surviving Yiddish theaters, the Soviet Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, and the remaining Jewish studies institutions, were shut down, their members often arrested and sent to the Gulag. The process culminated in January 1953 with the “Doctors’ Plot,” an exposé in the official Communist Party newspaper, Pravda, about a group of mainly Jewish doctors who had allegedly conspired to poison Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin. A short statewide campaign followed, though the doctors were ultimately acquitted and released from prison.

Being a Jew gradually came to be regarded as a kind of disability, which could only be overcome through extraordinary talent. This sentiment was expressed in the popular term “invalids of the fifth group,” a reference to the fifth line of internal Soviet passports, which revealed an individual’s ethnic identity.

At the time, Soviet Jews themselves were genuinely puzzled. The war had only increased the sense of patriotism that many felt toward the Soviet state. Although traumatized, orphaned, or otherwise devastated by loss, they generally looked forward to living in a peaceful society, free of Hitler. Many kept their heads low when they heard negative comments about Jews; compared to their wartime experience, such harassment seemed a minor nuisance. Beginning in the 1940s, however, Jews of all professions found themselves under increased scrutiny in the workplace, at school, and among friends and neighbors. They were expected either to keep quiet, or to publicly condemn the actions of the cosmopolitans, thereby proving their loyalties. Being a Jew gradually came to be regarded as a kind of disability, which could only be overcome through extraordinary talent. This sentiment was expressed in the popular term “invalids of the fifth group,” a reference to the fifth line of internal Soviet passports, which revealed an individual’s ethnic identity. After Stalin’s death, the prejudicial campaigns—such as those against “cosmopolitans”—slowed, but unwritten restrictions on where Jews could study and work intensified. Some fields, such as physics and engineering, remained accessible to Jewish students, but entry into programs in international relations, journalism, and the study of foreign languages was severely limited. Training in medicine or mathematics was usually available to Jews only at less prestigious universities.

From the end of the 1950s until the end of the 1980s, Jewish culture practically disappeared from public view, but Jews themselves remained highly visible. They seemed overrepresented among artists of all stripes, and among high-profile scientists and medical professionals, even as most urban Jews had to work a little harder than others to achieve their career goals and build the social networks crucial to advancement in the Soviet Union. Glass ceilings were everywhere. A Jew could easily become head of a regional hospital but not of a national research institution. Worse, as head of a regional hospital, a Jew had little freedom to hire other Jews, for fear of being accused of creating a clan.

To Jewish outsiders visiting or reading about the Soviet Union in the 1970s, Soviet Jews appeared to live under severe repression. The open hostility from non-Jews and the unwritten quotas and restrictions seemed evidence enough that the only solution was to flee. In addition, most Soviet Jews did not practice Judaism: They did not observe Jewish holidays or socialize in Jewish institutions, and they were prohibited from learning Hebrew, holding bar mitzvahs, or performing circumcisions. To American Jews, this suppression of religious expression suggested that Soviet Jews could not thrive in the Soviet Union.

But crucially, unlike American Jews, most Soviet Jews did not consider these practices important for their well-being. They wanted equality in the workplace and in their access to opportunities—but not badly enough to upend their lives and leave. In fact, Soviet Jews perceived themselves—and were perceived by their neighbors—as successful, well-connected, and savvy. They took pride in being able to achieve success despite the casual hostility they faced. Many of the Soviet Jewish jokes circulating at the time reflected such confidence: “Rabinowitch, can you play the violin?” “I don’t know, I’ve never tried!”

A propaganda poster depicting a Russian worker enslaved by Jewish masters, ca. 1930s.

“The Passportless Drifter,” cover illustration of the satirical magazine Krokodil, March 20th, 1949.

A cartoon referencing the so-called “Doctor’s Plot,” published in Krokodil magazine, 1953.

Perhaps this is why, in the 1970s, when the movement for Soviet Jewry created opportunities to leave the USSR for the US or Israel, only 246,000 Jews chose to do so. Even at the height of unwritten quotas and other discriminatory practices, two million stayed. (Several thousand people were denied visas, but most of them managed to leave in the late 1980s.) Notably, the “exodus” of Soviet Jews did not begin in earnest until after the fall of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, when all restrictions on Jews entering higher education and the workplace were lifted, but the political and socioeconomic situation became unstable. By 2018, another 1.7 million Soviet Jews and relatives had emigrated. Like Liza and her husband, many of them were ultimately pushed to leave by political and economic instability—and departed not with the sense of being liberated, but with ambivalence about the lives they were leaving behind. In this regard, they were not unlike many non-Jewish Soviet citizens, who wanted to leave but had no escape route. A popular joke from the ’90s captures the desire to marry Jewish for emigration privileges: “A Jewish wife is not a luxury, but a means of transportation.” Here, finally, was an upside to the “disability” of Jewishness: mobility.

IN THE US, the disconnect between American perception and the reality of Soviet Jewish experience haunted the new arrivals. They did not share a language, a common past, or an understanding of what it meant to be Jewish with their American counterparts. Most Soviet Jews were atheists and had been socialized to believe that they must hide their origins. This orientation was not easily reconciled with the unapologetic visibility of American Jewish culture, with its large community centers and extravagant bar mitzvah celebrations. Economic considerations aside, paying high synagogue membership fees for the privilege of being a Jew seemed like a cruel joke to people who had spent decades trying to overcome, or hide, their origins.

Ultimately, many Soviet Jewish immigrants found themselves with the familiar feeling that their contributions were not fully accepted or appreciated. Sure, university quotas no longer applied to them, but their ability to create networks—as important to career success in America as it had been in the Soviet Union—was significantly weaker than in the “old country.” Finally—to the immigrants’ surprise and disappointment—the American Jews that had fought so hard for their liberation were not quite as ready to embrace them as equals and as friends.

In his short story “Roman Berman, Massage Therapist,” Toronto writer David Bezmozgis, whose writing draws from his own immigration story, describes an episode in which a Canadian Jewish family hosts a welcome dinner for Russian Jewish immigrants. The Russian mother brings a homemade apple pie, the kind her own mother used to bake for special occasions. The host refuses to serve it, however, because it isn’t kosher. On the way home, the mother throws the pie into a dumpster.

When Liza R.’s friend told her, “I’m so tired of you Jews,” Liza was able to handle it because such attitudes were commonplace, expected. In North America, Bezmozgis’s dinner guest—the same age and background as Liza—is devastated when her supposed kin condescendingly spurns her prized contribution to a meal. Which situation is more emotionally painful might be hard to judge. But one thing is certain: Even in North America, Soviet Jews’ long history of rejection has not yet come to a definitive end.

Anna Shternshis is the Al and Malka Green Professor of Yiddish Studies and director of the Anne Tanenbaum Centre for Jewish Studies at the University of Toronto. She is the author of Soviet and Kosher: Jewish Popular Culture in the Soviet Union, 1923–1939 (Indiana University Press, 2006) and When Sonia Met Boris: An Oral History of Jewish Life Under Stalin (Oxford University Press, 2017). She is currently working on a book about Yiddish music created in Nazi-occupied Ukraine.