When Jews Go to the Polls

Recent polling offers potential answers—and raises additional questions—about what choices Jewish voters might make in the 2020 elections.

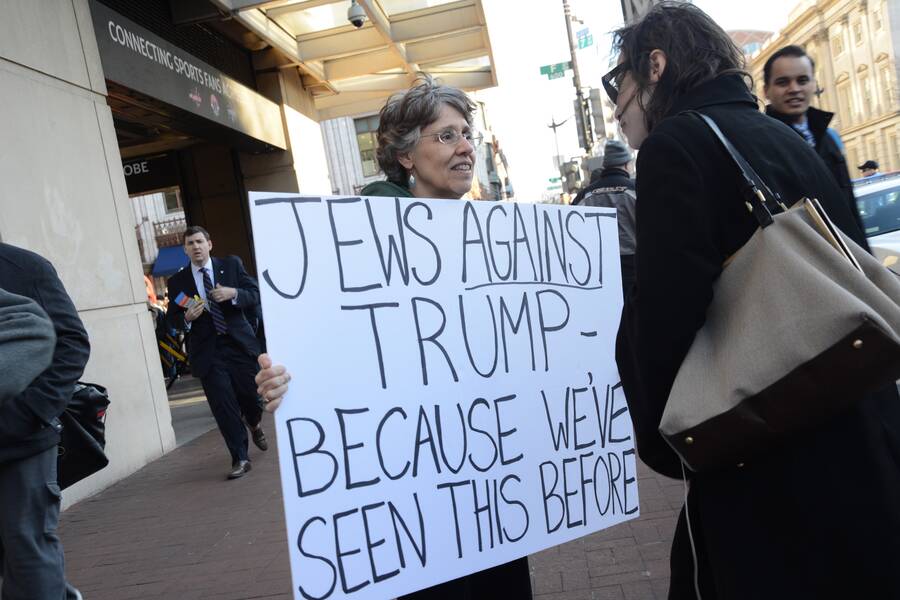

WHAT DOES the American Jewish voter want? It’s an increasingly relevant question in the American Jewish community as Donald Trump attempts to woo Jews by touting his pro-Israel record, a Jewish activist group pushes presidential hopefuls to take stronger anti-occupation stances, and two Jewish candidates have come to represent opposite ends of the Democratic Party’s political spectrum. A series of recently released polls—surveying Jews’ primary choices, their opinions on Trump and antisemitism, and their Israel politics—offers potential answers, and raises additional questions, about what choices American Jewish voters might make in the 2020 elections.

In some respects, this is business as usual: In every election cycle for a generation, pollsters have asked whether Jews will leave the Democratic Party, and every time, they have overwhelmingly remained within its ranks. (Barack Obama, for instance, won 78% of the Jewish vote in 2008, and nearly as much four years later.) Recent surveys suggest that this will remain true in this cycle as well. But the tumultuous specifics of the 2020 elections, including realignments within the Democratic Party, have also created unfamiliar terrain—which some pro-Israel groups, particularly an advocacy group called Democratic Majority for Israel (DMFI), are trying to use to their advantage.

On the most straightforward level, recent polling suggests that American Jewish voters—who voted for Hillary Clinton by an overwhelming margin in 2016—remain hostile to Trump. According to polling released this week by the progressive Jewish group Bend the Arc, around three-quarters of Jewish voters oppose the president: 66% hold “very unfavorable” views of Trump, and 9% hold “somewhat unfavorable” ones; 76% think Trump is racist, and 58% say he’s antisemitic. Bend the Arc’s survey was conducted in September, so its findings do not illuminate how more recent events, like Trump’s executive order on antisemitism, his “peace plan” for Israel/Palestine, or AIPAC’s ads calling Democrats’ policies antisemitic have affected Jewish voters’ views of the president and his party. But a mid-January 2020 survey by the Pew Research Group found relatively consistent results: according to this data, 62% of registered Jewish voters disapprove of Trump’s job performance, and 48% would be “angry” to see him re-elected, a higher percentage than for any religious affiliation besides atheist; an additional 18% would be “disappointed.”

One impediment to Trump’s attempt to endear himself to Jewish voters by presenting himself as the pro-Israel candidate is that Israel—now as in the past—appears to rank low among the issues that influence their voting patterns. Bend the Arc’s poll found that only 24% of Jewish voters rated Israel as a “top priority,” placing it far behind other issues (“gun safety laws,” “protecting Social Security and Medicare,” and “lowering healthcare costs” topped the list). This polling is consistent with years of findings: In polls from the Jewish Electorate Institute in both May 2019 and October 2018, for example, Jewish voters ranked Israel as the lowest of 16 policy priorities; health care ranked near the top.

Such findings, however, bracket a different question: to whatever extent the US–Israel relationship does influence American Jewish voters, what kind of policies are these voters looking for? A sharp increase in the visibility of Jewish anti-occupation activism in recent years has created a new phenomenon of Jews pushing Democratic presidential hopefuls on their Israel policies—from the left. The Jewish anti-occupation group IfNotNow, for instance, has pressed candidates to commit to leveraging US military aid and to skip the AIPAC conference in early March. Democratic candidates, meanwhile, are pushing the boundaries of what had been the Washington consensus on Israel/Palestine. Bernie Sanders has suggested he would leverage military aid to Israel to rein in Netanyahu’s annexationist policies. Elizabeth Warren has also said she’d consider conditioning aid, and recently committed to skipping this year’s AIPAC conference. Even Pete Buttigeg, whose policy proposals are generally far more moderate, indicated in the fall that he would be willing to use aid as leverage, though he has since walked back the comments.

In the view of some pro-Israel groups, however, these stances won’t appeal to American Jews, and could be enough to cost candidates some Jewish support. Mark Mellman—a pollster and the president of DMFI—thinks that the polls showing Israel as a low priority might not apply to this particular political environment. In Mellman’s view, the disruption of the previously bipartisan consensus on Israel/Palestine could make Israel a newly important issue to Jewish voters who still identify as pro-Israel. According to this logic, Israel has not traditionally been a decisive concern for Jewish voters because—compared with, say, gun control or health care—there has been little difference between the parties on the issue. But “if American Jews perceive a candidate as not pro-Israel, they will be much less likely to vote for him or her,” Mellman said. He pointed to a 2009 study he conducted for the Jewish Democratic Council for America, in which a hypothetical Democrat who was not identified as pro-Israel still beat a pro-Israel Republican among Jewish voters by three points, but a hypothetical pro-Israel Democrat beat the Republican by a whopping 45-point margin.

“Elections aren’t won by what people do overwhelmingly, they’re won at the margins,” Mellman said. While it’s highly unlikely a significant portion of Jewish voters will abandon the Democratic Party, a small group of Jewish defectors could swing a state like Florida. Mellman said he hopes that Jewish voters won’t have to make that choice. To that end, his group has attempted to influence the Democratic primary by targeting Sanders. DMFI—whose donors have close ties to AIPAC, though Mellman and AIPAC deny any official connection between the groups, despite recent reporting—has run ads against Sanders, the candidate that DMFI sees as the furthest from their position, ahead of caucuses in Iowa and Nevada. But the ads themselves don’t mention Israel and focus instead on Sanders’s health and electability. Mellman said he believes this anti-Sanders strategy reflects American Jews’ concerns about the frontrunner. In a Pew poll conducted January 6-19, Sanders was the preferred candidate of just 11% of Jewish voters.

Although Mellman acknowledged that there is no clear evidence that Sanders’s low numbers in the Pew poll were related to his views on Israel, Mellman nevertheless claimed that Sanders’s Israel policy was a likely explanation. “Sanders is Jewish himself, he presents views on many issues that align fairly well with those of many American Jews,” Mellman said, “so you have to believe that the big discordant note is Israel.” Other political writers have pointed to a variety of factors that could influence Sanders’s low support among Jews in the Pew poll, including fears of antisemitic backlash to a Jewish candidate, concerns about electability, and changes in Jewish class since the Jewish socialist heydey. The Jewish voting bloc also has higher-than-average levels of educational attainment, a factor that has been more characteristic of Warren and Biden voters than Sanders voters (though this has begun to change as Sanders has cemented his frontrunner status).

Joel Rubin, Sanders’s recently hired Jewish outreach director, said that “if DMFI felt that it could win on Israel among the Democratic electorate, it would run ads on Israel.”

Logan Bayroff, communications director for the liberal “pro-Israel, pro-peace” advocacy group J Street, disputes Mellman’s assessment of Sanders’s chances among Jews. “It’s interesting to see Mark Mellman make the same argument made by the Republican Jewish Coalition, who for years have been saying that Israel’s going to cost Democrats the election,” he said. Bayroff pointed to Republicans’ unsuccessful attempts to use the Obama administration’s Iran nuclear deal to sway Jewish voters: a 2012 J Street election night poll found that of the Florida Jewish voters who watched Mitt Romney’s ads criticizing the deal, 56% said the ads had no effect on their vote, and 22% said the ads made them more likely to vote for Obama. Mellman himself was heavily involved in the effort to defeat the Iran deal: he served as a consultant to the AIPAC-associated group Citizens for a Nuclear Free Iran, which spent tens of millions lobbying senators against the deal. But Mellman and other Jewish groups against the deal, like the Anti-Defamation League and many Jewish Federations, failed to persuade their community: polls showed that most Jews favored the agreement. Jewish support for Obama remained sky-high in 2012. (Mellman now opposes the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the deal, he told The Intercept; prominent Jewish politicians originally against the deal, like Sen. Chuck Schumer and Rep. Elliot Engel, eventually came to defend it against Trump.)

To Bayroff, Mellman’s concerns about Sanders represent another miscalculation. “Any Democratic nominee is going to pulverize Trump when it comes to Jewish voters,” Bayroff said. And rather than increasing in importance based on the candidates’ positions, Israel might matter even less to American Jews in 2020, who are especially concerned about the threat of Trump and other pressing issues like climate change, Bayroff predicted. That would be consistent with how Jewish voter priorities have trended during the Trump era. According to J Street’s election night polls, in 2016, just 9% of voters chose Israel as one of their top two voting priorities. In 2018, that number decreased to 4%.

J Street has not endorsed a candidate in the primary, but it is raising $1 million to support the Democratic candidate against Trump in the general election. Mellman said that one of DMFI’s priorities is defeating Trump, but he declined to say what role they will play in the general election if Sanders is the nominee. “I don’t think that’s going to happen,” he told me. “So I’m not going to speculate on unlikely future events.” Earlier this week, Mellman announced that the group would no longer be running ads against Sanders after Nevada, and that it would be pivoting to focus only on congressional races. However, a later statement claimed that DMFI “will continue to be deeply involved in the presidential race,” and the group is still running sponsored email ads with The Forward celebrating its Iowa anti-Sanders ads and calling for readers to sign a petition urging Democrats to select a “pro-Israel Democrat who can beat Donald Trump.”

Rubin, Sanders’s Jewish outreach director, argues that Sanders would “do very well against Donald Trump in the Jewish community.” Rubin said he’s hesitant to put too much stock in the Pew poll of primary voters, given how the primary race has already changed since January. If Jewish voters are less interested in Sanders because of his views on Israel, Rubin said, that’s because Sanders’s position on Israel has been misrepresented. In reality, Rubin said, Sanders is generally in line with American Jews: pro-Israel, but critical of the government and Netanyahu. A recent study—commissioned by the Ruderman Family Foundation and conducted in early December by Mellman’s polling group—found that 80% of American Jews identified as “pro-Israel”: 29% were “pro-Israel” but critical of “many” Israeli policies, while 28% were “pro-Israel” and critical of “some” policies, and 23% were supportive of Israeli policies. Among those who felt a weaker connection to Israel, almost 40% cited Netanyahu’s support for Trump as the reason, while 25% cited Israel’s treatment of Palestinians.

Mellman, for his part, said that his problem with Sanders is less about what the candidate says and more about the fact that he has campaign surrogates like Linda Sarsour and Amer Zahr who support the boycott, divestment, and sanctions movement. (Attacks on Sanders in the Jewish press have accused him of being insufficiently Jewish in addition to complaining about his positions on Israel; Sanders has defiantly insisted on his pride in his Jewish identity, most recently with a video ad emphasizing that he’d be the first Jewish president and targeting Trump’s antisemitism.)

“This is a time-tested political tactic: if you can’t effectively attack the candidate, attack his supporters. These smear tactics are designed to undermine the movement backing Bernie,” Rubin said.

Rubin flew to Los Angeles last week to speak at a candidates forum at Valley Beth Shalom synagogue. Although DMFI co-sponsored the event, Rubin said it was important for the Sanders campaign to be there and to communicate with the Jewish community. “It was fun, it was hard, and I made my pitch and some things I got cheered for and some things I got silence and some things I maybe heard a little boo or two,” he said. “I had a dozen people around me afterwards standing there talking in vigorous debate like Jews do.”

THE DEBATE ABOUT which policies American Jews are most likely to support is ultimately about who can claim to truly represent the views of American Jews—and answers to that question may also be affected by a marked shift in Jewish voters’ concerns about antisemitism.

In response to questions posed in Bend the Arc’s poll, 90% of respondents said they thought antisemitism had increased over the past four years (with 63% saying it had increased “a lot”). Forty-four percent said they thought antisemitism was more of a problem in the Republican Party, while 26% said they thought it was more of a problem in the Democratic Party. These numbers contrast with the rhetoric of many mainstream Jewish organizations, which often present antisemitism as a both-sides issue and which spend more time criticizing Democrats like Ilhan Omar than Republican white nationalists like Steve King.

“It’s very hard for advocacy organizations to change direction overnight,” said Rubin. “For years they’ve been pushing a narrative that criticism of Israel is the core antisemitic threat. But what actually matters to American Jews right now in terms of our health and safety is the condition of the communities in which we live in the United States. The result is that many of these organizations are not positioned to pivot and deal with the antisemitism crisis here at home.” Sanders, Rubin argues, is using the best strategy to fight antisemitism: forming a diverse coalition with the goal of combating hate.

Until there’s more polling of Jewish voters that takes into account recent primary developments—including the rise of Sanders as the frontrunner, the fall of Joe Biden, and the emergence of Michael Bloomberg—and that measures Trump against Sanders in a head-to-head matchup, it’s hard to predict exactly how Jewish voters will act if the two face off in the general. But the community’s persistent disapproval of Trump—and the fact that his pro-Israel stance, which is to the right of most American Jews’, hasn’t made a dent in those numbers—is telling. It’s true that Sanders isn’t a typical Democratic candidate, and given the intensity of the smears against him, Rubin might have to work hard to convince Jewish voters to fully embrace him. But Trump also isn’t the typical Republican candidate imagined in Mellman’s 2009 survey—and Jewish concerns that Trump stokes antisemitism are pervasive. If Jews are going to leave the Democrats—even in the marginal numbers that win or lose elections—it’s hard to imagine they’d do it for Donald Trump.

A previous version of this story identified DMFI as an organization that conducts both polling and advocacy. In fact, DMFI does not do polling. Mark Mellman, DMFI’s president, does his own polling independent of DMFI’s work.

Mari Cohen is associate editor at Jewish Currents.