Post-Soviet Realism

Zoya Cherkassky-Nnadi’s oeuvre looks frankly at the immigrant experience.

Untitled, 2021, mixed media on paper, 6 x 9 in

IN THE WOODS, an orgy is in progress. Its participants surround a white blanket, where they’ve abandoned their picnic: Tomatoes and cucumbers lay strewn beside a bowl of hard-boiled eggs, and a jar of pickles juts out of an open Adidas bag. While one woman removes her underwear, two others are already entangled with a trio of expressionless men. Two of the women’s faces are covered or turned away, while the other stares blankly into the eyes of the man penetrating her. For a portrait of idyllic debauchery, it’s strangely passionless, focused on the mechanical unfolding of the sex acts, set comically against the meadow’s tranquility.

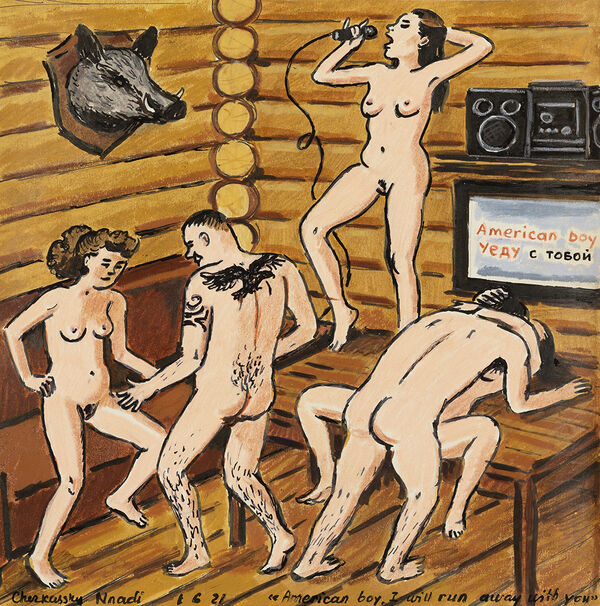

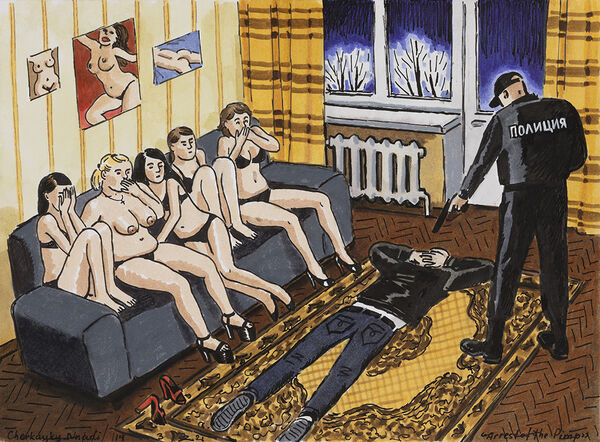

The portrait, Le Déjeuner Sur L’Herbe (Luncheon on the Grass)—conceived as a reconfiguration of Édouard Manet’s controversial 19th-century study of the female body—is part of post-Soviet Israeli artist Zoya Cherkassky-Nnadi’s in-depth exploration of the daily lives of sex workers. Recently exhibited online by Fort Gansevoort Gallery in a show called Women Who Work, which closed last October, the series of more than 50 mixed media works on paper employs Cherkassky-Nnadi’s signature bright colors and bold lines, combining the idealist aesthetics of Soviet Realism and the exuberance of comics. American Boy, I Will Run Away with You shows a nude karaoke party, in which one woman stands on a table belting Kombinaciya’s early ’90s hit “American Boy” while a couple has sex beneath her. In Arrest of the Pimp, a group of distraught women sits on a couch as a policeman holds a man lying face down on the rug at gunpoint. With characteristic candor, Cherkassky-Nnadi captures moments of routine violence and glimpses of friendship and solidarity between women making a life on the margins.

Le Déjeuner Sur L’Herbe, 2021,

mixed media on paper, 7.5 x 11 in

American Boy, I Will Run Away with You, 2021, mixed media on paper, 7.5 x 8 in

Her sarcastic, painfully honest style has been both lauded and condemned for its unflattering picture of Israeli society’s treatment of Soviet immigrants.

These paintings represent both a departure from and a deepening of Cherkassky-Nnadi’s ongoing project. While Women Who Work marks the first time she has dealt extensively with sex work, the paintings continue her examination of the friction between marginalized communities and the hegemonic majority. Cherkassky-Nnadi came to Israel as a teenager with her family from Kyiv, Ukraine, in 1991. As her work has come to prominence over the last two decades, her sarcastic, painfully honest style has been both lauded and condemned for its unflattering picture of Israeli society’s treatment of Soviet immigrants. By deconstructing the immigrant experience in all of its painful minutiae—from bloody adult circumcisions to rabbinic home inspections to ensure adherence to the laws of kashrut to workplace sexual harassment—Cherkassky-Nnadi punctures the nation’s self-congratulatory narrative, in which the nearly 1 million immigrants who arrived in the 1990s were simply accepted and seamlessly integrated.

Her work first sparked public outcry with her 2003 solo exhibition, Judaica Collection, which incorporated imagery from antisemitic artifacts and unsettling depictions of Jews across time, including a golden broach inspired by the Nazis’ yellow star and illustrated Haggadah pages featuring Hasidic figures with bird-shaped bodies. Even before the opening, Liora Minka, a member of the Tel Aviv City Council, accused Cherkassky-Nnadi of antisemitism and appealed to the mayor and Israel’s attorney general to intervene. But the show went on, and the artist’s star soon began to rise; the esteemed Israel Museum would later purchase work from the exhibition for its own collection.

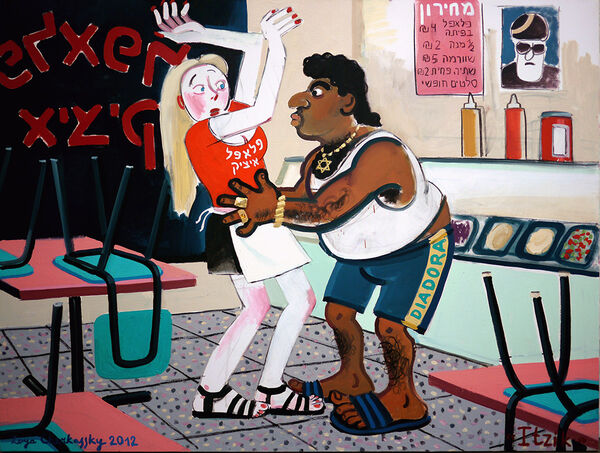

Two years later, Cherkassky-Nnadi relocated to Berlin to continue developing her work. It was there, at a distance from both her disintegrated motherland and her unfriendly adoptive homeland, that she started processing the traumatic experience of immigration and acclimation she shared with so many Soviet émigrés. When she returned to Israel in 2009, her work began to reflect this exploration, highlighting themes of displacement and marginalization. Seeking a community with which to explore these feelings, she joined four other post-Soviet female painters—Olga Kundina, Anna Lukashevsky, Asya Lukin, and Natalia Zourabova—to form the New Barbizon Group. Named for the 19th-century Barbizon School, a cohort of French painters who favored Realism at a time when Romanticism reigned, the New Barbizon artists shared an interest in capturing elements of social reality often overlooked or kept out of view. New Victims (2016), for instance, shows Soviet families disembarking from an El Al airplane, their scarves and winter hats clashing with the palm trees in the distance, while a woman at the bottom of the stairs waits with an unwelcoming expression and a bundle of Israeli flags. (The painting takes its title from Cherkassky-Nnadi’s grandmother, who would sigh at the sight of an airplane, saying, “Here come the new victims.”) In Itzik (2012), a dark-skinned falafel vendor gropes a pale, blonde waitress wearing a miniskirt. By loudly invoking pernicious stereotypes—the lecherous Mizrahi man, the promiscuous Russian woman—the painting implicitly rebukes these caricatures while also surfacing genuinely fraught relations between ethnic groups that dwell together at the bottom of social and economic hierarchies.

Cherkassky-Nnadi unsettles “how Israelis want to see themselves,” explains Sagi Refael, an Israeli curator and art advisor based in Los Angeles. Her work “unapologetically reveals a vicious circle of stereotypes, pointing out oppression, economic gaps, and generational confrontations within various ethnic groups.” Cherkassky-Nnadi herself notes that responses from within the post-Soviet community have been mixed. “Some very much identify with the paintings,” she told me, while others are offended by their portrayals, “asking me why I only paint the bad things, and not the successes of aliyah [emigration to Israel].”

New Victims, 2016,

oil on linen, 55 x 90.5 in

Itzik, 2012,

oil on canvas, 59 x 78.5 in

Cherkassky-Nnadi unsettles “how Israelis want to see themselves.”

Though Women Who Work advances this investigation into unromanticized depictions of post-Soviet life, Cherkassky-Nnadi didn’t initially conceive of these works that way. “I started these drawings without any preconception,” she said in a conversation that accompanies the exhibit, “but then I gradually realized that most of the women I was depicting were . . . post-Soviet women” (an association between Eastern European women and prostitution also lives as a stereotype in the Israeli consciousness). While some of the scenes are imagined, others were inspired by documentaries or YouTube videos of raids on Russian brothels. In one untitled piece, a group of partially dressed women watches Intergirl, a popular Soviet drama, which follows a nurse who sells her body to tourists by night. In another, in which a sex worker slips on tights beside a naked client, the woman’s position mirrors a 2015 painting from Cherkassky-Nnadi’s Soviet Childhood series, as does the design on the wallpaper behind her. The clothes, interiors, and cultural references emerge from collective memories of the Soviet Union. Though the women no longer live in that collapsed, faraway place, their lives continue to be defined by it—psychologically, socially, and economically.

Untitled, 2021,

mixed media on paper, 7.5 x 10.5 in

Though the women no longer live in that collapsed, faraway place, their lives continue to be defined by it—psychologically, socially, and economically.

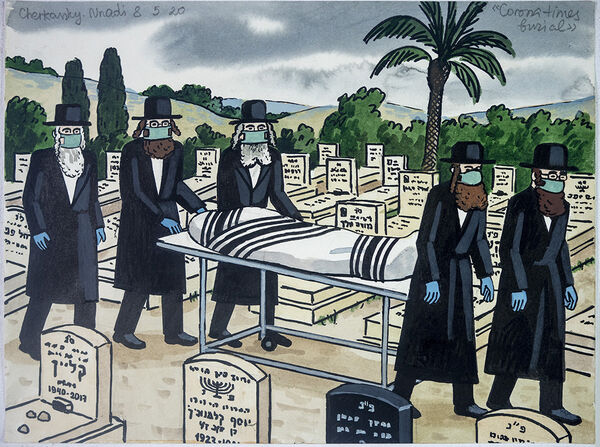

The inescapability of personal and historical trauma, and its impact across generations and geographies, unites Women Who Work with Lost Time, Cherkassky-Nnadi’s earlier pandemic-era exhibit, featuring works created over the course of the first few weeks of the pandemic, shortly after shelter in place orders dramatically altered lives worldwide. “Being present at a historical moment when everything falls apart is one of the main issues in my work,” she told me. “It is the eternal fear of catastrophe or irreversible change that is about to happen, and you have no control over it.” This online exhibition, also organized by Fort Gansevoort Gallery in the spring of 2020, was initially inspired by a YouTube video of a Haredi wedding ceremony in a cemetery, a ritual meant to banish the coronavirus. The ceremony was a reincarnation of the 19th-century Eastern European ritual known as a kholere khasene (cholera wedding) or shvartse khasene (black wedding), in which a poor or disabled man and woman united to ward off an epidemic. Fascinated by the ritual and the meeting points between past practices and contemporary hardships, Cherkassky-Nnadi began drawing Black Chuppah, a centerpiece of the exhibition, in which a somber bride and groom clad in black unite under a dark shroud, framed by graves. Other pieces featured in Lost Time consider the ways the pandemic has altered ancient rituals. In Corona Times Burial, undertakers carry a body in shrouds while wearing surgical masks. An Open Air Minyan depicts Haredi men praying together in a field at a distance, seemingly indifferent to the plein air.

Corona Times Burial, 2020, watercolors and markers on paper, 9.25 x 12 in

An Open Air Minyan; 2020; ink, watercolor, and wax crayons on paper; 9.25 x 12 in

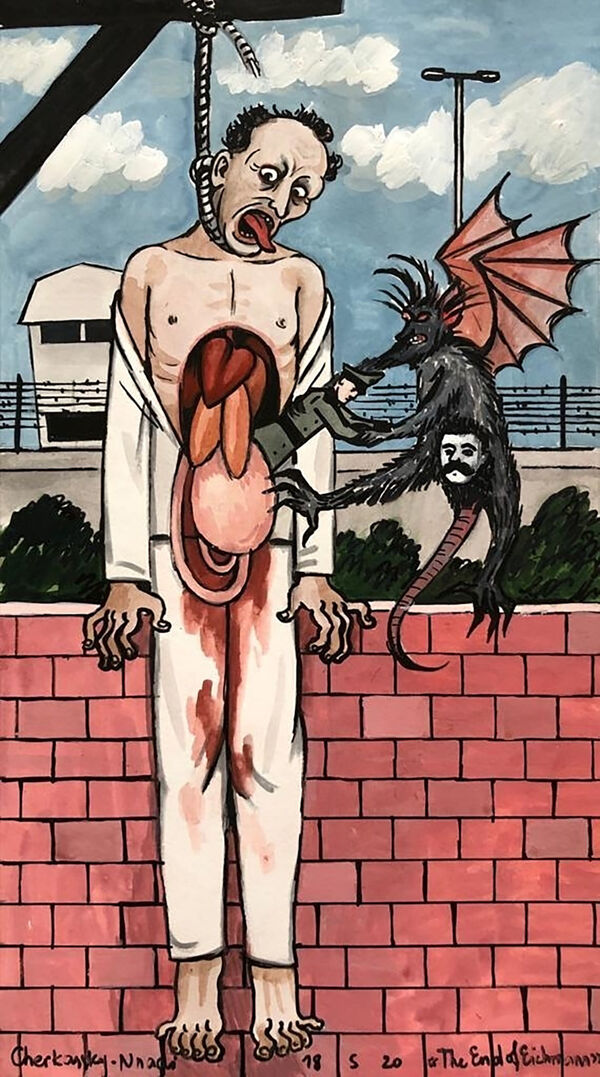

Elsewhere in the exhibit, the suffering of the present gives way to the suffering of the past, focusing on visceral scenes of devastation—tsarist pogroms and Nazi massacres—from Russian Jewish life between and during the world wars. In Demjanjuc, a demonic figure sits on a pile of concentration camp prisoners beneath a blood red sky. The Angel of Death / Stalin is a diptych: One side shows the Grim Reaper wearing an SS uniform, while the other depicts Stalin gazing down at a pile of Nazi flags and insignias, above which floats the final verse of “Chad Gadya”: “And then God came and killed the Angel of Death.” The image provocatively frames the murderous Soviet leader as God, in his capacity as a slayer of Nazis. The End of Adolf Eichmann builds on this theme while relegating Stalin to a lowlier position; the painting shows the organizer of the Final Solution hanging from a gallows while a winged demon, his genitals covered with Stalin’s face, pulls out his guts. In these haunting, claustrophobic images, Cherkassky-Nnadi unleashes the devils that have been lying in wait beneath the acerbic humor of her past works.

The Angel of Death / Stalin; 2020;

ink, watercolor, and wax crayons on paper; 12 x 9.25 in each

The End of Adolf Eichmann; 2020; watercolor, marker, and tempera on paper; 15.75 x 8.75 in

In the haunting, claustrophobic images of Lost Time, Cherkassky-Nnadi unleashes the devils that have been lying in wait beneath the acerbic humor of her past works.

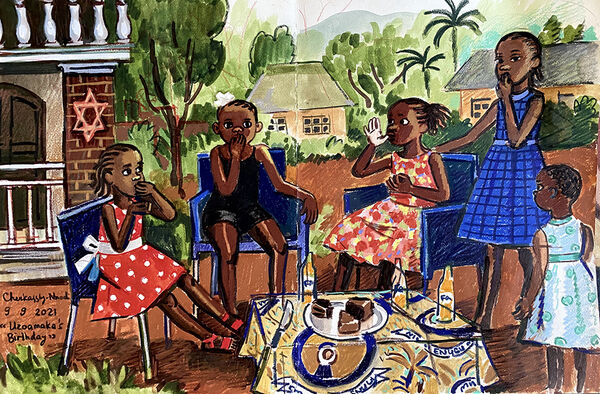

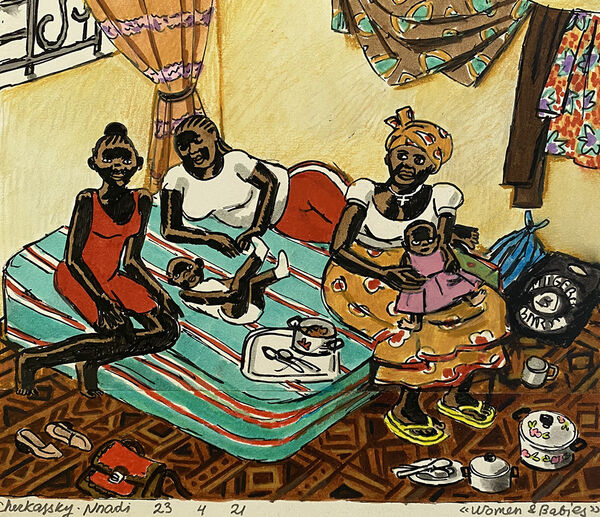

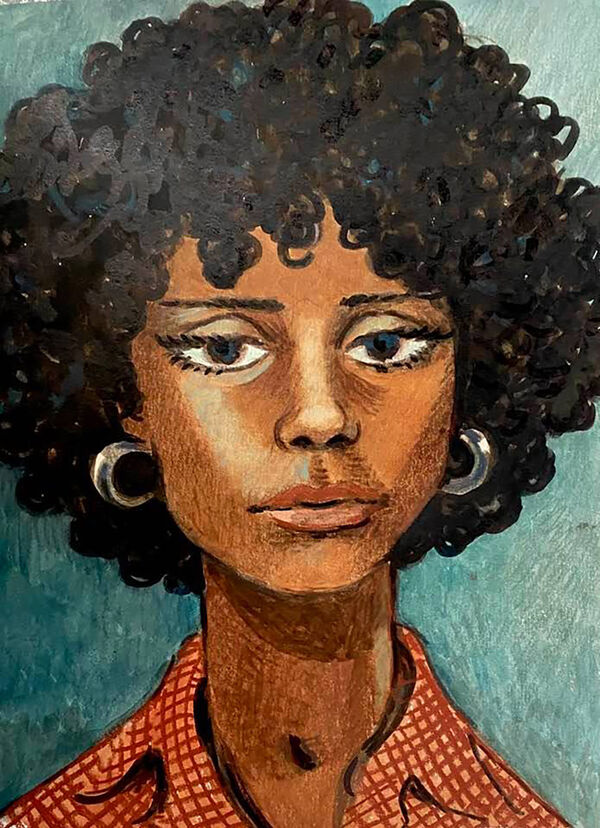

Lost Time may have also afforded her a sense of release from the demons of Jewish life, freeing her to look elsewhere, at other refugee groups living on Israel’s margins. Inspired by her husband, Sunny Nnadi, whom she met near the Central Bus Station in Southern Tel Aviv over a decade ago and asked to pose for a painting, she began focusing on the lives of African immigrants in Israel. On her Instagram page, which serves as a testing ground for new projects, she has recently displayed portraits of Sunny and their daughter, Vera, along with studies of Nigerian communities in Israel. Though many of the scenes are set in spaces operated by and for African communities, they often contain elements of menace or alienation—a police officer at the restaurant counter, a Haredi child gawking through a barbershop window. A visit to her husband’s familial home this year has sparked a series documenting rural and domestic life in Nigeria itself, chronicling the artist’s experience “becoming part of a large Igbo family.”

Uzoamaka’s Birthday, 2021,

mixed media on paper, 12 x 18.5 in

New Dress for Vera, 2021 mixed media on paper 23x29 5 cm

Women and Babies, 2021 mixed media on paper 20x23 cm

The paintings created in the aftermath of her trip to Nigeria notably double back to the Soviet Union, introducing an exploration of Black life and interracial encounters in the USSR.

Blackface in the Soviet Cinema

2021 mixed media on paper

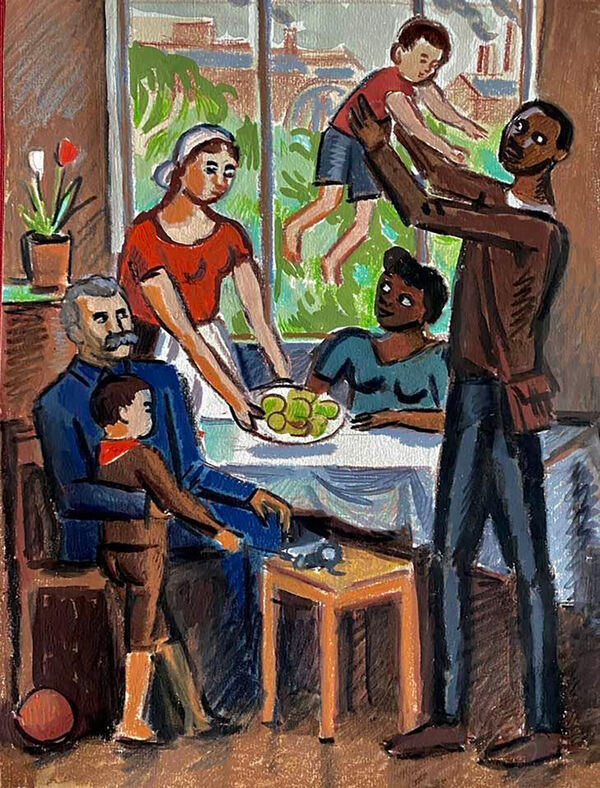

The paintings created in the aftermath of that trip notably double back to the Soviet Union, introducing yet another thread: an exploration of Black life and interracial encounters in the USSR. These works move between more personal experiences—like her first time encountering a Black person as a child—and broader reflections on Soviet aspirations to racial equality alongside expressions of Soviet racism. The turn was inspired by a 1932 work by her great-grandfather, Abram Cherkassky, which she rediscovered at an exhibition in Kyiv and decided to recreate. The painting, called Arrival of Foreign Workers, shows a Black couple being welcomed into the home of a white Soviet family. In the original, the domestic warmth and camaraderie of the scene is complicated by the Black family’s caricatured features, in comparison to Cherkassky-Nnadi’s more naturalistic rendering. “My great-grandfather’s painting was a trigger,” she explained. “It seemed right at the center of my interest in cultural clashes.” She was inspired to research the history of such encounters, resulting in images of African students at Patrice Lumumba Peoples’ Friendship University in Moscow (named for the Congolese independence leader) and notable Black American ideological émigrés to the USSR, and in a series exploring blackface in Soviet cinema, highlighting famed Soviet actors like Lyubov Polishchuk and Evgeniy Leonov appearing in Black roles in full makeup.

Arrival of Foreign Workers, 1932,

71 x 77.5 in

After Abram Cherkassky’s “Arrival of Foreign Workers,” 2021, mixed media on paper

“My great-grandfather’s painting was

a trigger. It seemed right at the center

of my interest in cultural clashes.”

Taken together, these images present a nuanced and unsentimental portrait of race in the Soviet Union. But even as the pieces refuse nostalgic oversimplification, they exude a tenderness that distinguishes them from her previous work. As she works to reconcile her various contexts, perhaps Cherkassky-Nnadi is finally finding her way home.

A previous version of this piece identified the song being sung in the painting American Boy, I Will Run Away with You as a song by the British artist Estelle. In fact, the painting references a song of the same name by the Russian band Kombinaciya.

Rotem Rozental is a scholar, curator, and writer based in Los Angeles, where she serves as executive director and chief curator at the Los Angeles Center for Photography (LACP). Her writings have appeared in publications such as Tablet, The Forward, and Artforum. Her book, Pre-State Photographic Archives and the Zionist Movement, was published by Routledge in 2023.