Porzellan Manufaktur Allach

Robert Russell’s recent exhibition exposes idyllic trinkets as sites of Nazi domination and imagination.

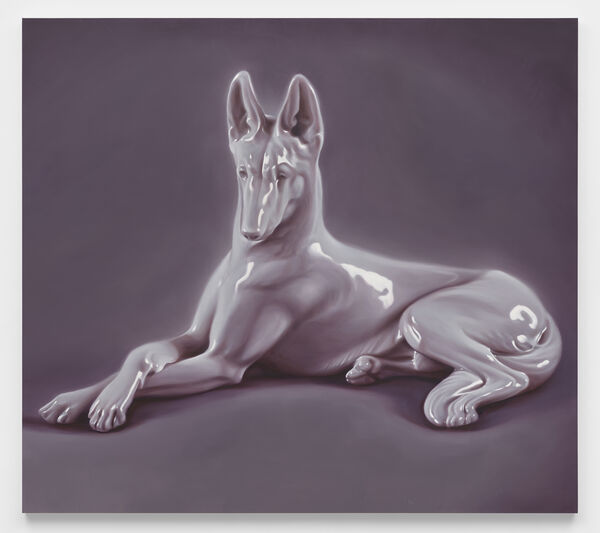

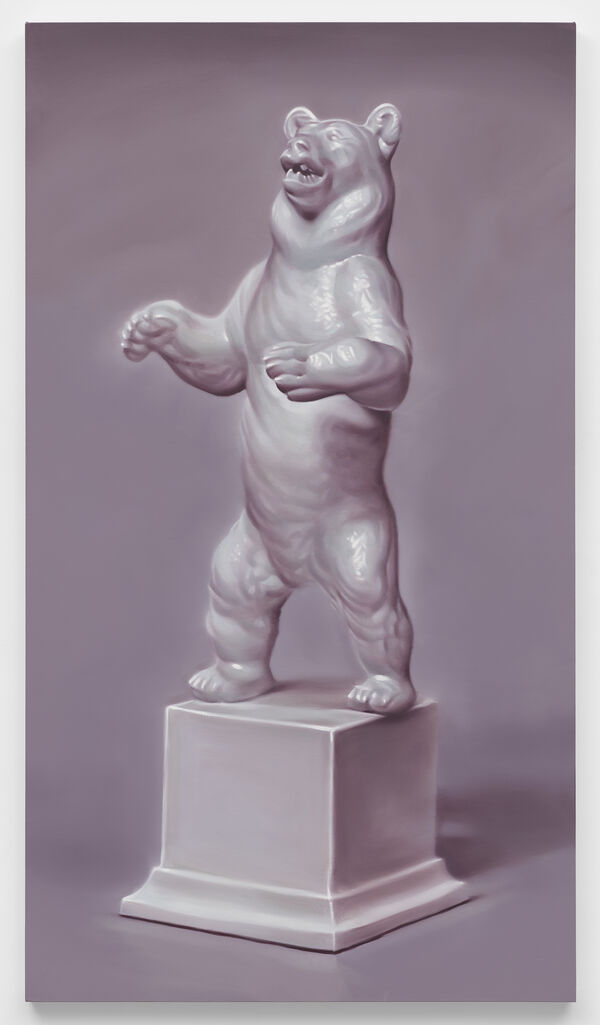

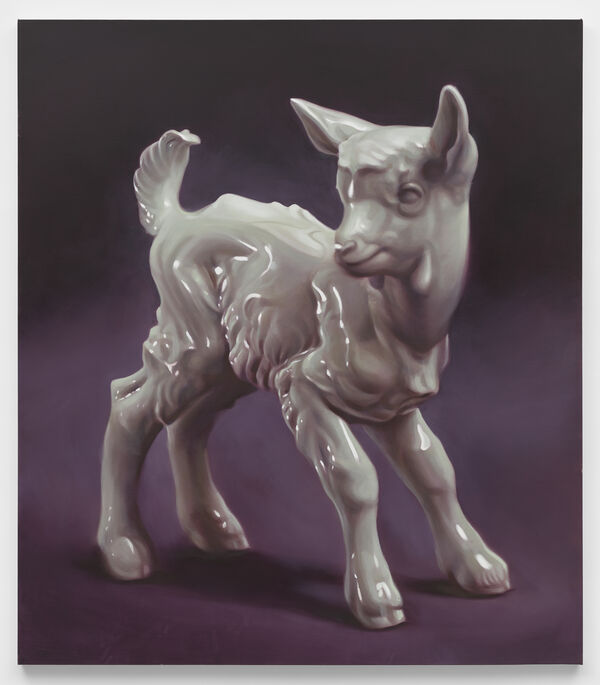

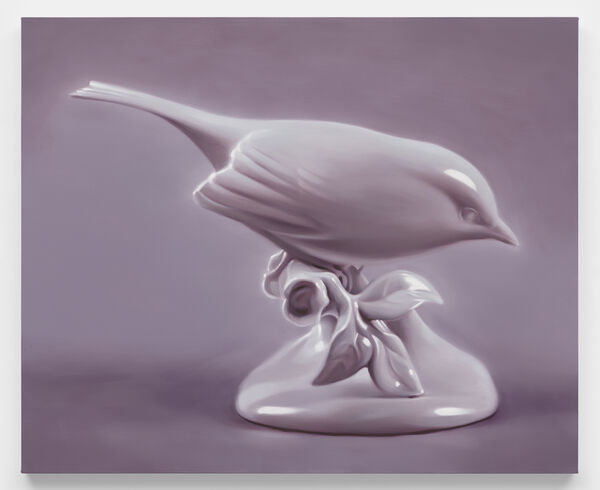

Robert Russell has found an emblem of collective trauma hiding in plain sight—where else?—on eBay. In 2020, the artist came across images of delicate porcelain teacups on the website, from which he created a series of large, photorealist paintings depicting the objects against dark backgrounds—the quaint charm of the familiar household items offset by the defamiliarizing scale and void-like surroundings. As Russell proceeded with his research into porcelain, he came across images of a very different kind of trinket: figurines produced in the 1930s and ’40s by the German company Allach Porcelain Manufacturing. The factory in the small town outside Munich, he learned, was partially acquired by the SS not long after it opened in 1935. SS head Heinrich Himmler, the architect of the “Final Solution,” had a passion for so-called Germanic art and understood that aesthetics played a vital role in shaping the collective consciousness of the Aryan nation. It was his personal office that made a 45,000 Reichsmark investment in the factory, eventually giving him control of 45% of its output. The porcelain statuettes popular in Third Reich households included battling bears and German shepherds, as well as peasants, soldiers, and mothers with children; these figurines constructed a pastoral idyll, effectively inserting the Nazi imagination into domestic spaces. Under Himmler and the SS, Allach produced an assortment of such animal statuettes and representations of the idealized volk of the Third Reich, as well as portrayals of historical and political figures (Prussian soldiers, a bust of Hitler), and everyday objects, including candleholders and vases. As the factory continued to ramp up production, a second location was established just outside of Dachau concentration camp in 1937. By 1940, with skilled German workers drafted into the war effort, enslaved laborers from the camp began assembling these emblematic Aryan crafts. The factory was a popular stop on guided tours that Himmler gave to other SS officials. Visitors were gifted the figurines—mementos sourced from an inferno, whose horrendous conditions were largely occluded from the world outside the camp.

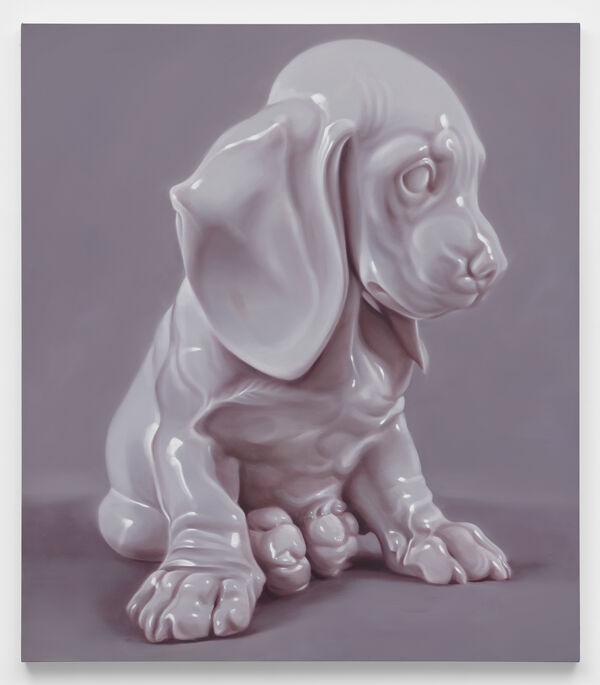

The alluring snapshots of cheerful statues that Russell encountered online harbored this genocidal history. They also pointed toward a still-extant market that obfuscated the figures’ original context. By translating the photographs into large-scale paintings, which were originally shown in an exhibition titled Porzellan Manufaktur Allach at the Los Angeles gallery Anat Ebgi in March 2023, Russell works both to exhume and to exorcise, claiming these objects from obscurity and contending with the unsettling presences that persist within them. With some canvases nearly seven feet tall, the paintings are seductive and haunting. Unlike the actual trinkets, which one might pass by without a second thought, Russell’s paintings—in which the figurines are isolated and enlarged—ask us to consider the objects’ origins: Who made them? And what became of their makers?

It is fitting that Russell stays away from the Allach figurines that portray overt Nazi themes and visual emblems, such as the swastika-bearing Luftwaffe officers, and confines himself to painting the animals. More unnerving than even the symbols that readily summon the brutality of the Third Reich are the bunnies and deer, with their apparent innocence. Their shiny veneers are emblematic of precisely what was so dangerous about the world imagined by the Nazis: Its system of human destruction was overlaid by a benign facade of happy unity. In bringing these figurines to the fore and defamiliarizing them, Russell simultaneously exposes the ongoingness of a quaint dissemination of Nazi ideology and obstructs this particular route of transmission. “Now, when you research Allach, you find my project and the writing around my work,” Russell said. “I infected this place. I wanted that to happen. I want to demolish that market.”

Kleiner Schaeferhund, 2022, oil on canvas, 80 x 90 in

Berliner Bär, 2023, oil on canvas, 80 x 45 in

Ziege, 2022, oil on canvas, 80 x 70 in

Kohlmeise, 2023, oil on canvas, 40 x 55 in

Liegendes Rehkitz, 2022, oil on canvas, 80 x 70 in

Sitzend Junger Dackel, 2022, oil on canvas, 80 x 70 in

Rotem Rozental is a scholar, curator, and writer based in Los Angeles, where she serves as executive director and chief curator at the Los Angeles Center for Photography (LACP). Her writings have appeared in publications such as Tablet, The Forward, and Artforum. Her book, Pre-State Photographic Archives and the Zionist Movement, was published by Routledge in 2023.