Open

The images that comprise Open evoke the almost spectral omnipresence of a malevolent state power.

All artwork: 2021, C-print mounted to ink on paper, 11 x 14 in

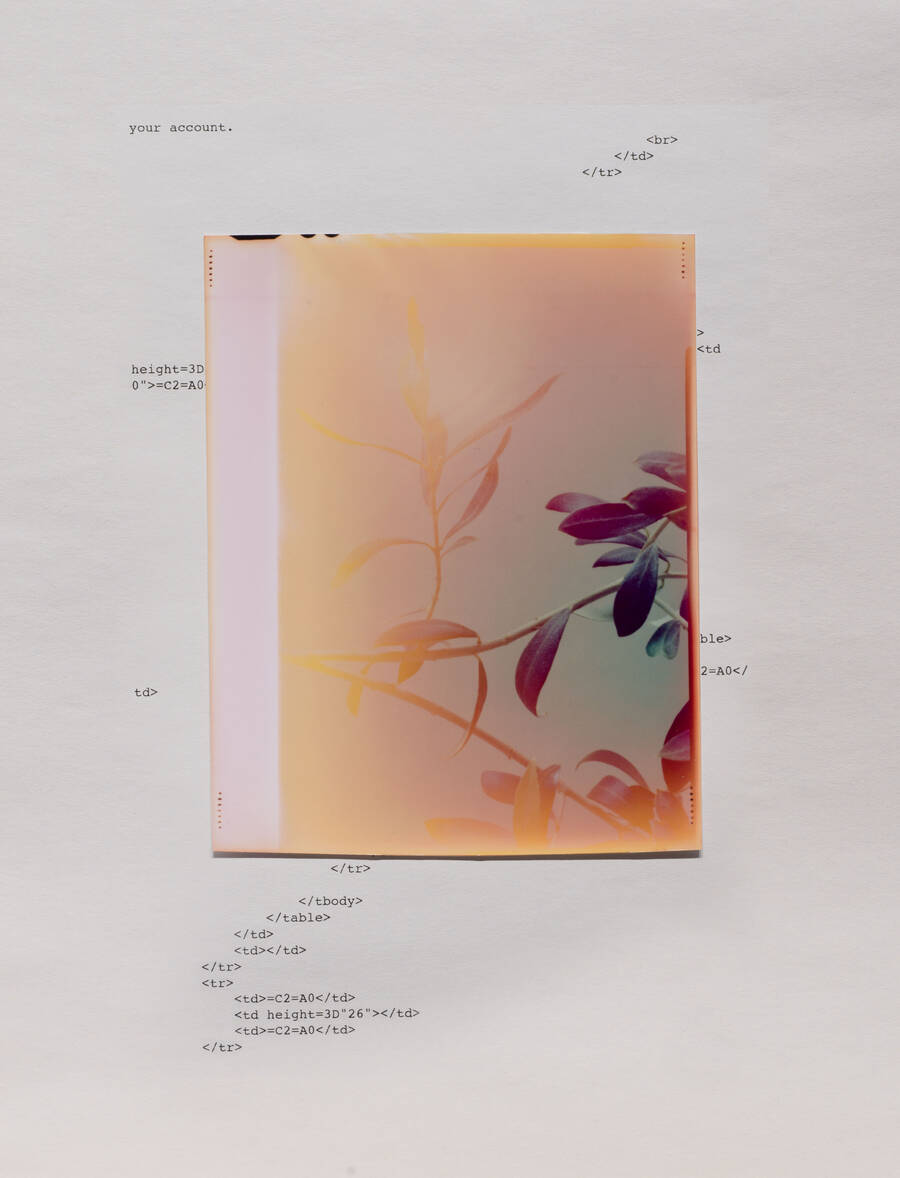

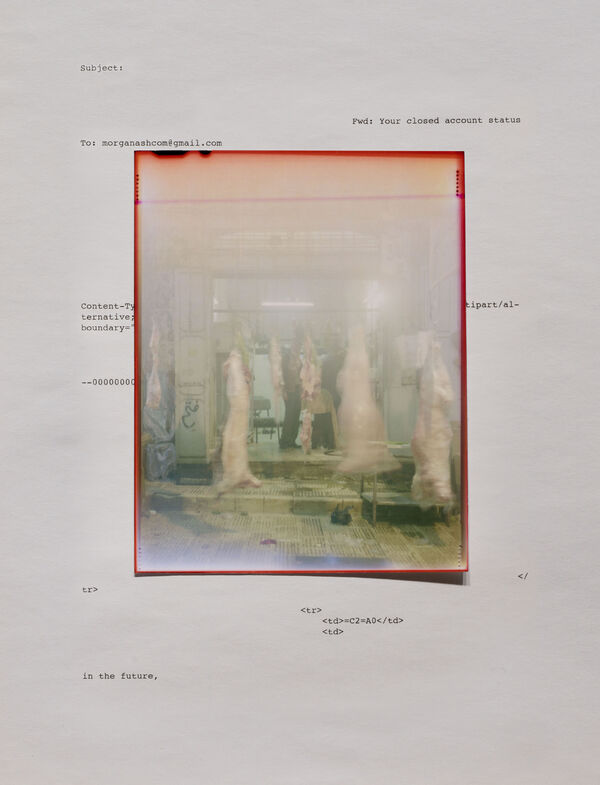

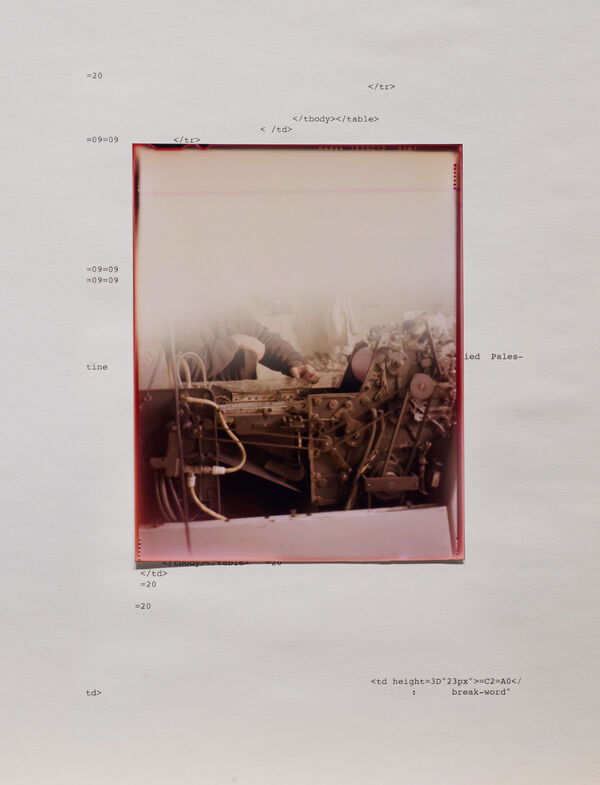

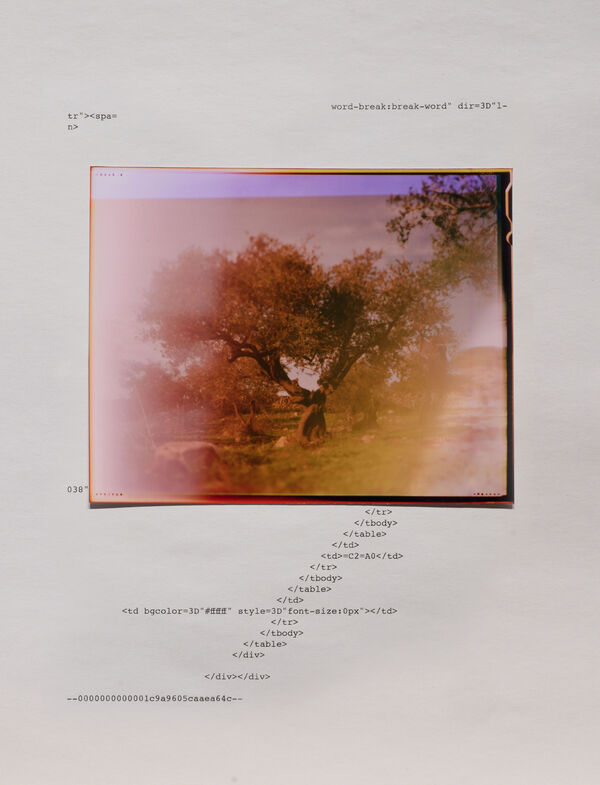

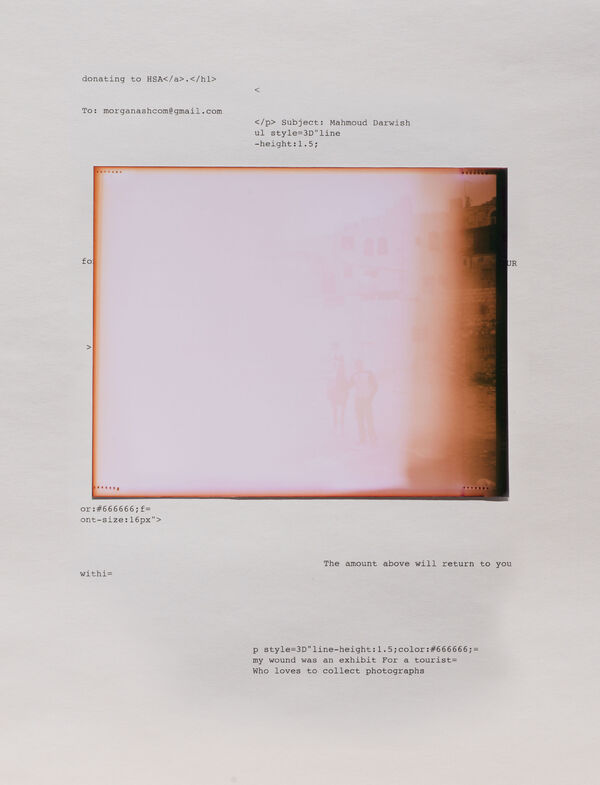

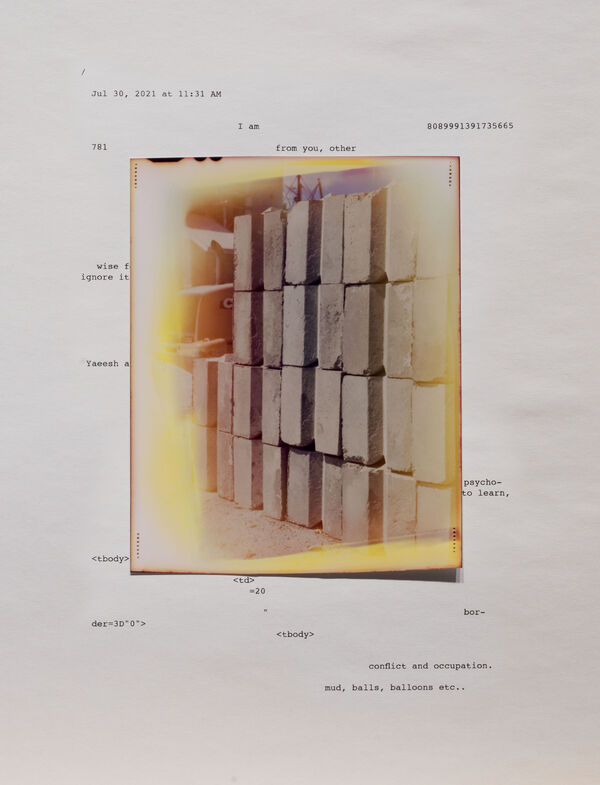

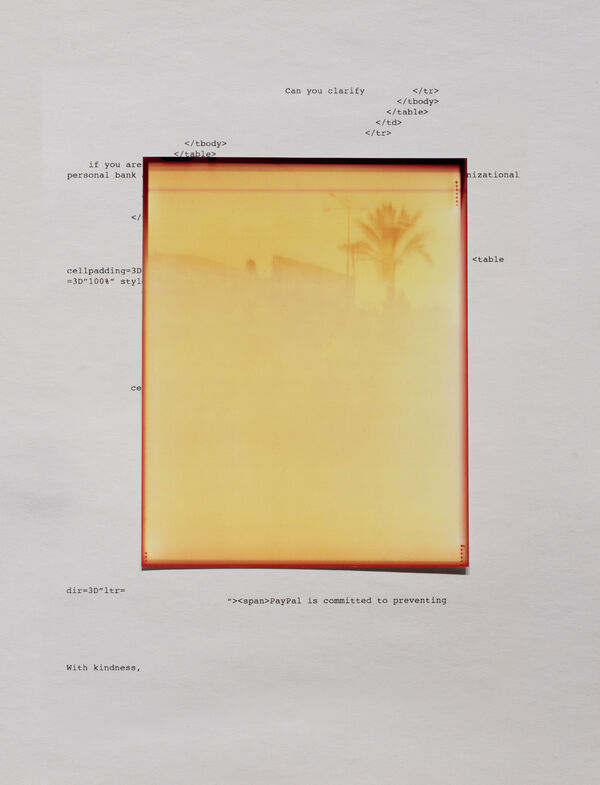

Morgan Ashcom’s photographs of life in Palestine are imbued with a supernatural aura. Images of stacked cement blocks, butcher displays of hanging carcasses, posters commemorating martyrs, and other quotidian scenes are obscured by brilliant washes of color. This ombré effect, which gives the impression of a haunting, recalls the work of 19th-century practitioners of “spirit photography” who experimented with doubled exposures or reflective surfaces, creating layered images that make visible the ghostly ambiences that seem to cling to certain people and objects.

But the images that comprise Ashcom’s Open—a series collected into a limited-run book last year—evoke another kind of spectral phenomenon: the omnipresence of a malevolent state power. In fact, their defining aesthetic feature was produced by a confrontation with that power. When Ashcom was on his way home to the United States from a 2009 trip to the West Bank city of Nablus, where these photographs were taken, Israeli soldiers opened his box of unprocessed film at a checkpoint, exposing its contents to the light and presumably ruining them. Yet when he returned to the photographs more than a decade later, he discovered they weren’t ruined at all; they were, in a way, completed.

The officers’ intrusion inadvertently materialized the metaphysical force haunting all the land between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, revealing the way the Israeli state looms over the dead and dispossessed Palestinians whose decimated lifeworlds—homes, farms, cemeteries—are the necessary condition of its existence. One of Ashcom’s images, for example, shows an orchard of olive trees. But unlike in familiar idyllic renderings, here the image of the iconic fruit tree, a symbol of Palestinian identity and a cornerstone of Palestinian agriculture, is eroded by the photograph’s discoloration, recalling the Israeli state and settler practice of razing and vandalizing the slow-growing trees to make way for more settlements. The bursts of color, which meet the eye innocuously enough, actually cloud the scenes depicted, echoing the ways that Israeli settler colonialism makes ordinary the negation of Palestinian life.

Indeed, as Ashcom’s images evince, these lethal structures of state violence are woven into the very fabric of daily life. During his time in Nablus, Ashcom met Wajdi Yaeesh, the director of the Human Supporters Association, an underfunded grassroots nonprofit, founded after the 2002 Israeli invasion of the city to serve local women and youth contending with the material realities of the occupation. Moved by their work, Ashcom donated the photos to be sold as part of a 2021 fundraiser for the organization. But when Israel’s convoluted and restrictive internet bureaucracy prevented Yaeesh from confirming his own identity to various financial institutions and fundraising platforms, thousands of dollars in funds were returned to donors. Ashcom later added excerpts of the HTML code from emails sent as part of the identity verification process to the backdrop of the photographs, surfacing the way that the routine processes Israeli and international forces present as rational and indispensable are actually ghosts in the machine of a brutal occupation.

A product of the checkpoint and labyrinthine financial bureaucracy, Open records an outsider’s passing but consequential experiences of the ordinary cruelty of the apartheid regime to which Palestinians are regularly subjected. Through this aestheticization of everyday violence, Ashcom transforms an encounter in which the Israeli state attempted to destroy a visual record of Palestinian life into what he calls “speculative fictions containing the potential to imagine a reversal of histories.” The series thus summons narrative possibility out of what the colonial regime seeks to eradicate.

Zoé Samudzi is a sociologist, art writer, and contributing writer for Jewish Currents.