Understanding Apartheid

Embracing a radical critique of Israeli apartheid is a precondition for bringing it to a just end.

A billboard put up by the Israeli human rights group B’Tselem ahead of Biden’s visit to Israel and the West Bank.

at The height of the Unity Intifada in May 2021, as Palestinians demonstrated from Gaza City to Haifa to Ramallah, Rep. Rashida Tlaib, the only Palestinian American member of Congress, demanded an end to Israel’s “apartheid government.” Two days later, Reps. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Cori Bush joined her in tweeting, in reference to Israel: “Apartheid states aren’t democracies.” The use of the “apartheid” label—and the rejection, from even a small minority of legislators, of the claim that Israel is “the only democracy in the Middle East”—signaled a break with US political orthodoxy.

These interventions were not only buoyed by the landmark Palestinian uprising but enabled by a series of recent, high-profile reports from major human rights organizations. In January 2021, the leading Israeli watchdog group, B’Tselem, deemed Israel a “regime of Jewish supremacy from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea.” A few months later, in April, the global advocacy organization Human Rights Watch (HRW) described a reality of “apartheid and persecution” maintained for the purpose of “privileging Jews over Palestinians” and involving “an institutionalized regime of systematic oppression and domination.” These organizations aimed to consolidate an anti-apartheid analysis as common sense; their work seemed to give many people permission to speak. Throughout the spring and summer of 2021, solidarity statements and open letters referencing the reports flowed from scholarly and cultural organizations around the world. (Tlaib, too, cited both B’Tselem and HRW.) The momentum continued into 2022: In February, Amnesty International published its own extensive study of Israel’s apartheid against Palestinians, calling it a “cruel system of domination.”

These legacy human rights organizations were in some ways surprising sources for a new wave of anti-apartheid analysis, given how long they had publicly avoided and privately objected to that very form of critique. Even the editor of the HRW report, on the ground since the organization began working in Palestine in the late 1980s, has said that until recently he could “not imagine the word ‘apartheid’ applying to the Israeli and Palestinian context.” As recently as 2001, HRW actively opposed the efforts of Palestinian civil society groups to garner global agreement, at the UN World Conference Against Racism, that Israel should be declared “a racist, apartheid state.” One leading representative of the organization said at the time that he “personally spent hours trying to persuade Arab and Palestinian colleagues to amend this and other language.” In the years that followed, HRW and Amnesty kept their distance as trade unions, social movements, and cultural figures around the world responded to the Palestinian call for boycott, divestment, and sanctions of Israel. They also stayed largely silent as workers and students who organized boycott initiatives and campus “Israeli Apartheid Week” events were censored and punished.

The reports that a new generation of researchers and advocates have propelled into being base their reasoning in international law, which defines apartheid as a crime against humanity—one in which “inhuman acts” are “committed for the purpose of establishing and maintaining domination by one racial group of persons over any other racial group of persons and systematically oppressing them.” Amnesty’s report, which builds on B’Tselem’s shorter position paper and HRW’s detailed legal analysis, is the most extensive and ambitious of the three. All the reports locate the practice of apartheid in the entire territory—including the land inside Israel’s 1948 boundaries as well as the West Bank and Gaza—but Amnesty’s pushes back most explicitly against the “false perception that the military regime in the OPT is separate from ‘the civil regime in annexed East Jerusalem and pre-1967 Israel.’” Amnesty concludes that Israeli control amounts to “one system of oppression and domination” throughout the territories and within the ’48 lines, and goes even further by asserting that the Israeli apartheid regime also impacts the rights of Palestinian refugees.

At the same time, the human rights groups often imagine that Israel, before the 1967 War and occupations, was merely an imperfect democracy. Over time, as B’Tselem puts it, “the situation has changed.” Although the HRW report acknowledges that Israel imposed martial rule on its Palestinian citizens from its founding until 1966, it all the same suggests that a “threshold” has been “crossed” over the years. This reading naturalizes the most formative event in the Palestinian national consciousness, the Nakba of 1947–1949, when Zionist and Israeli forces expelled three-quarters of the native Palestinian population from their homes and homeland. Even the Amnesty report, which argues that the founding of Israel as a state of the Jewish people precluded the possibility of full equality for non-Jews, also seems to suggest that the state’s original promise to grant “complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants” could have been met if “given full effect through legislation”—a contradiction in terms. (Instead, as the report notes, Palestinians’ rights have been further eroded through the passage of quasi-constitutional laws like the nation-state law of 2018, which further codified the guarantee of a state of the Jewish people, not a state for all its citizens.) Amnesty’s report also avoids discussing what underwrites the state’s architectures of inequality: Neither “colonialism” nor “Zionism” is discussed.

Elements of Amnesty’s messaging have seemed difficult to reconcile with its researchers’ findings on Israeli apartheid, as if the organization is uneasy with the implications of its own analysis.

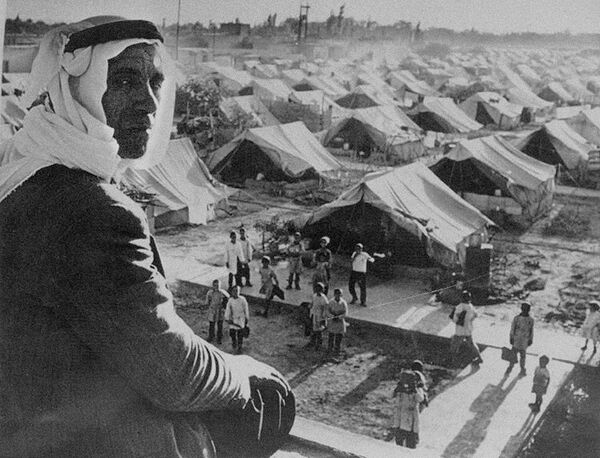

A Palestinian man in the Jaramana Refugee Camp in Damascus, Syria, 1948.

Since the release of its report, elements of Amnesty’s messaging have seemed difficult to reconcile with its researchers’ findings, as if the organization is uneasy with the implications of its own analysis. In the wake of publication, Amnesty Secretary General Agnès Callamard was at pains to draw a distinction between the state’s inbuilt hierarchies and its corresponding practices: “We are not criticizing the fact that there is a Jewish state,” she said. “What we are calling for is on the Jewish state to recognize the rights of all people living under their control and on their territories.” Such statements imagine that formal rights can be provided as a remedy to apartheid, even within an overarchingly unequal constitutional structure. So when, in the report, Amnesty calls for urgent local and international action “to dismantle the system of apartheid against Palestinians,” it’s hard not to ask, as Palestinian scholar-activists Soheir Asaad and Rania Muhareb have done: “Dismantle what,” exactly?

Here a distinction between liberal and radical critiques of Israeli apartheid comes to the fore. The reports’ critiques of the state’s content but not its form ultimately obscure more than they illuminate about the nature of Israeli apartheid, since Israel’s racially discriminatory regime cannot be understood absent an examination of its ideological origins. “Racism is not an acquired trait of the Zionist settler-state,” Fayez Sayegh—founder of the Palestine Liberation Organization’s (PLO) Palestine Research Center, a global center of scholarship on Palestine from the 1960s through the 1980s—wrote in 1965. “Nor is it an accidental, passing feature of the Israeli scene . . . It is inherent in the very ideology of Zionism and in the basic motivation for Zionist colonization and statehood.”

Sayegh’s analysis is foundational to a rich Palestinian intellectual tradition that understands apartheid as an inevitable outcome of Israeli settler colonialism, and a key ideological and legal-institutional vehicle for its continuance. To say “settler colonialism” is to name a distinctive phenomenon in which the settler arrives with the intent to stay and supplant native sovereignty—not merely to rule, but to replace through forced assimilation, geographical containment, juridical erasure, and killing. This requires the racialization of the natives—their classification as other and inferior—in order to justify their domination and displacement. In his 1970 book, Settler Colonialism in Southern Africa and the Middle East, also published by the Palestine Research Center, Syrian intellectual George Jabbour emphasizes that “the distinguishing feature of settler colonialism” is the “declared espousal of discrimination, on the basis of race, colour or creed.” The radical critique rooted in this work from the 1960s and ’70s understands apartheid not as a deviation from Israeli democracy, but as a governance modality of settler colonialism—a direct derivative of Zionism’s state project. Palestinian scholars have emphasized that decolonization need not be predicated on settler evacuation, as occurred in former European colonies like Algeria or Mozambique. They insist that the issue has never been the Jewish claim to belonging and staying, but rather, the Zionist claim to sovereignty and domination.

To agree on what it would take to end apartheid, we must first understand what apartheid is. The essence of the definition has been contested since apartheid was formally enacted in South Africa in 1948. The anti-colonial analysis advanced by South African thinkers and movements, and then by Palestinian scholars like Sayegh, was watered down in the post-Cold War conjuncture of the mid-1990s by liberals who sought to uphold the deeply unequal international order that colonialism had wrought. Returning to the more radical critique and the lineage of Palestinian thought that brought it forward—and recognizing how this intellectual tradition was obscured from view in the first place—is a necessary precondition for working to truly dismantle apartheid, down to its settler-colonial foundations.

A roadblock at the entrance to an area under Military Rule in a cluster of Arab villages known as the “Triangle,” February 1952. For nearly 20 years after the founding of the Israeli state, 85% of Palestinians in Israel lived under strict military rule.

An apartheid-era notice on the coast near Cape Town, South Africa, July 7th, 1976.

In 1948, as the full brutality of the Nakba unfolded in Palestine, apartheid was formally instituted in South Africa. From the outset, African intellectuals and leaders understood the system of oppression under which they lived as the legal and political architecture of colonialism; the South African Communist Party called apartheid “colonialism of a special type.”

At the Palestine Research Center, founded by Sayegh, intellectuals and activists drew on this analysis to put the Palestinian struggle in international context, exploring Zionism’s relationship to other settler-colonial movements. In his canonical 1965 text Zionist Colonialism in Palestine, Sayegh wrote that the Zionist settler state had

learned all the lessons which the various discriminatory regimes of white settler-states in Asia and Africa can teach it. And it has proved itself in this endeavour an ardent and apt pupil, not incapable of surpassing its teachers. For, whereas the Afrikaner apostles of apartheid in South Africa, for example, brazenly proclaim their sin, the Zionist practitioners of apartheid in Palestine beguilingly protest their innocence!

Sayegh suggested that Israeli settler colonialism was more similar to the settler-colonial apartheid systems of southern Africa than to other European metropolitan colonial enterprises. Unlike the latter such projects, Sayegh noted, the Zionist settler state was not “an imperial outpost of a metropolitan home-base,” but “a home-base in its own right.” But it too positioned the natives as members of a “lesser” race; this required the assertion of a Jewish “national oneness”—as distinct from Palestine’s existing “non-Jewish communities”—which inevitably produced “three corollaries: racial self-segregation, racial exclusiveness, and racial supremacy.” Whereas in colonies principally devoted to the goals of exploitation and extraction, “European colonists have as a rule deemed the continued presence of the indigenous populations ‘useful,’” in the Zionist settler state, as in instances of settler colonialism more broadly, the primary principle was not just one of racial hierarchy, but also of “racial elimination.” In the case of “those remnants of the Palestinian Arab people who have stubbornly stayed behind in their homeland in spite of all efforts to dispossess and evict them,” Sayegh wrote, the Zionist project has underpinned and necessitated the practice of apartheid—the relegation of the natives to “their own ‘Bantustans,’” borrowing the South African term for the ghettoized enclaves reserved for Black inhabitants.

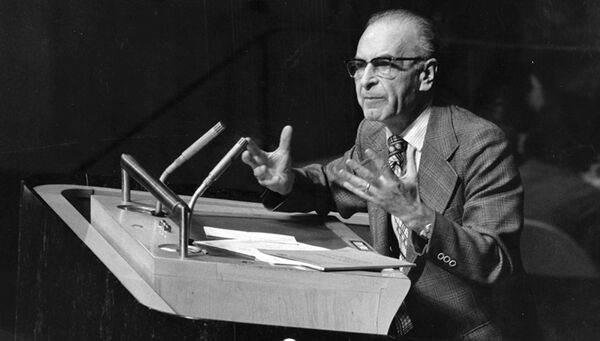

Fayez Sayegh addresses the UN General Assembly in 1976.

These analyses, which predate the 1967 expansion of Israel’s frontier and the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, present apartheid as a phenomenon rooted from the outset in the very constitution of the settler state. Sayegh was not alone in illuminating how the state encoded racial discrimination into law from its earliest years. In his 1965 book Zionism & Racism, Hasan Sa’b, another scholar associated with the Palestine Research Center, showed that the state’s construction of a legal category of Jewish nationality—as distinct from Israeli citizenship—codified a racial distinction between settlers and natives. Israel, Sa’b explains, discriminates among its citizens “on racial and national grounds,” maintaining “one law for its Jewish citizens and another law for its Arab citizens.” A year later, in The Arabs in Israel, the lawyer, scholar, and activist Sabri Jiryis detailed how the state’s institutions “are dedicated to the interests of the Jewish citizens above all others and that at best the Arab is only a second-class citizen.”

Among Palestinian intellectuals, then, the Naksa—Israel’s annexation of East Jerusalem and occupation of the remaining Palestinian territories at the end of the 1967 War—was understood to intensify and expand an already-existing apartheid dynamic. Writings from this period trace how Israel’s methods of domination in the post-’67 territories originated in the land it had held since 1948. For example, Palestinian sociologist Elia Zureik, writing in 1979, noted that Israel’s first several hundred Jewish-only colonial settlements were built within the 1948 territory, and involved the dispossession and displacement of Palestinian citizens and their concentration in particular geographic zones. Zureik used the term “internal colonialism” to describe Israel’s oppressive practices within its 1948 borders, and detailed its fusion of “official” apartheid structures—such as racially discriminatory legal codes—with “informal” ones, like the sharp economic inequality between Palestinians and Jews. Together, he wrote, these facets of the apartheid system “manifested in segregation in housing, land ownership, education, interpersonal contact, modes of political organization and occupational distribution, not to mention the area of marriage.”

Many of the early attempts to analyze apartheid as continuous across the pre- and post-’67 territories appeared in the Journal of Palestine Studies, which was established in 1971 by a group of Palestinian scholar-activists who had founded the Institute of Palestine Studies in 1963. At a time when denying the very existence of Palestinian peoplehood had significant cachet in Israeli and Western political and academic circles, the purpose of both the journal and the institute was to preserve a historical record of Palestinian intellectual work on the question of Palestine, and to create a home for new knowledge production on the subject. The journal was attuned to what South African scholar Alfred Moleah—later an ambassador under the post-apartheid government led by the African National Congress (ANC)—described in a 1981 article as the “South African parallels” inherent in “the nature of the state of Israel [as] a settler colony.”

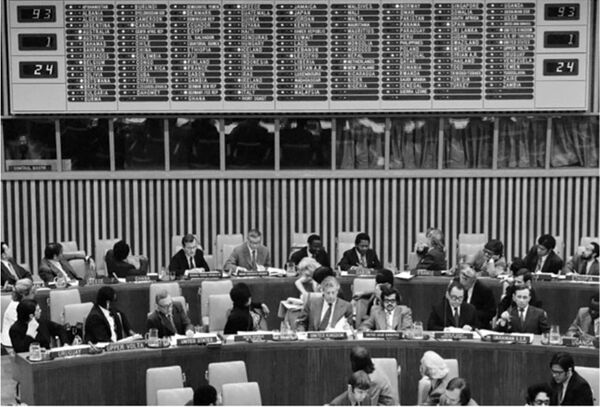

In drawing on the anti-apartheid framework, Palestinian intellectual and political leaders were not merely building a case by analogy; forums like the Palestine Research Center and figures like Sayegh influenced South African scholars’ thought in turn, and set the stage for significant political developments at the United Nations. In the early 1960s, as a wave of decolonial struggles unfurled across Africa and Asia, Third World states became the majority bloc within the UN, organizing themselves into the G-77 and leading the General Assembly—with the support of the self-styled anti-imperialist Soviet delegation—in passing a series of resolutions that employed the language of self-determination in calling for an end to colonialism in all its forms. Among the Third World bloc’s achievements was the passage of the 1973 Apartheid Convention, which bore the imprint of the South African and Palestinian intellectual traditions. The convention not only defined apartheid as a regime of racial domination, but also framed it as a phenomenon closely connected to colonialism; it named physical violence, acts of murder and torture, and other human rights abuses as elements of apartheid, but also detailed as core features the expropriation of land, the creation of separate reserves and ghettos, the exploitation of the labor of the subjugated racial group, and the obstruction of their social and economic development. Under this definition, apartheid required the same remedies as other manifestations of colonial rule and foreign occupation: collective liberation and land restitution.

Among the Third World bloc’s achievements at the UN was the passage of the 1973 Apartheid Convention, which bore the imprint of the South African and Palestinian intellectual traditions.

Kenneth Kaunda, President of Zambia, speaks at the International Seminar on Apartheid, Racial Discrimination, and Colonialism in Southern Africa, held in Kitwe, Zambia, on July 25th, 1967.

Sayegh saw in the international condemnation of racism an opportunity to take his work beyond intellectual exposition. Drawing on the human rights treaty opposing racism that the UN had adopted in 1965—the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination—and inspired by the Black freedom struggle in North America, he sought to adapt his racial theory of Zionism into a legal analysis, demonstrating that Israel’s policies violated the anti-racism convention. Sayegh also led efforts to amend the UN Decade Against Racism documents—a series of proposals to implement UN treaties on racism—to add reference to Zionism wherever apartheid, colonialism, or racial discrimination were mentioned. This work culminated in 1975 with the UN’s adoption of General Assembly Resolution 3379, which declared Zionism to be “a form of racism and racial discrimination.” In encoding a robust anti-racist analysis of Zionist settler colonialism in UN documents, Sayegh and the Palestinian thinkers of his milieu bridged Afro–Asian struggles and took part in the Third World upheavals of the time. In a moment of potentially revolutionary reconfiguration, the more radical postcolonial states and leaders sought to use the established forum of the UN to bring about a sweeping transformation of the international order—an effort that stands in marked contrast to the liberal campaigns of the coming decades, most of which would instead propose tinkering around the edges of the status quo.

By the 1980s, the power and prospects of the anti-imperial Third World liberation project were fading. Most of the colonized nations had by now achieved formal independence—with Namibia, South Africa, and Palestine among the significant exceptions—and many were already trapped in neocolonialism, the net of economic, political, and cultural factors through which former imperial powers have maintained control over other nations. In the face of the prevailing Third World majority at the UN, the West engaged in counterrevolutionary tactics, most notably the economic restructuring programs engineered through the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, which compromised the political agency of many postcolonial states by making them reliant on Western credit. These shifts diminished the UN’s significance as a site of international politics, instead elevating the importance of bilateral arrangements, regional bodies, and specialized trade and financial institutions. The end of the Cold War also affected the Third Worldist movement, since it neutralized the former Soviet Union as a provider of arms, funding, and diplomatic support to anti-imperialist fronts in the Global South.

Together, these developments created the conditions in which a liberal politics of human rights and formal equality displaced more radical understandings of apartheid, which considered anti-apartheid movements to be inseparable from the wider anti-imperial struggle. This shift was cemented as official apartheid crumbled in southern Africa: Namibia finally achieved independence in 1990, just as the prisoner releases and transition processes that would culminate in the ANC’s 1994 election to power were beginning in South Africa. In the eyes of the world, apartheid was bracketed as a historical anomaly; to liberals, its demise was evidence of the end of history, permission to consign settler-colonial racism—and white supremacy more broadly—to the past. This was made easier by the fact that, though the UN had condemned Zionism as a form of racism, it had never undertaken a thorough exposition of Israeli apartheid analogous to its work on southern Africa (which included a series of resolutions, a set of institutional mechanisms established to document and oppose apartheid in South Africa, and a direct reference to southern Africa in the 1973 Apartheid Convention). The liberal impulse to believe that the age of apartheid had ended was assisted, in 1991, by the PLO’s entry into the Madrid–Oslo “peace process.” The Oslo process, which brought the PLO within the US and Israeli sphere of influence without promising the establishment of a Palestinian state, has been widely criticized in the decades since for setting up a sovereignty trap: Under its terms, incremental gains in Palestinian autonomy became conditional on the approval of the Israeli settler sovereign and its imperial patron, the United States, setting up a framework in which the achievement of sovereignty could be constantly deferred.

The developments of the 1980s and ’90s created the conditions in which a liberal politics of human rights and formal equality displaced more radical understandings of apartheid.

Oslo also helped cement the liberal turn in understandings of apartheid. As a precondition for entering the process, the PLO famously agreed to renounce armed struggle as a legitimate tactic of national liberation; less well known is that it also consented to rescind the 1975 UN resolution finding that Zionism is a form of racism, removing a hard-won link in the chain of reasoning by which activists had hoped to draw the world into a recognition of the illegitimacy of the Zionist legal regime. Today, when Israel is said in legal quarters to be practicing apartheid, the case is usually made by demonstrating how the state’s policies fit the criteria of the international legal definition. Had the PLO not rescinded the 1975 resolution, such a legal analysis might be considered superfluous—the fact that Israel maintains a regime of racial domination would be an established finding of the international community. In such a world, perhaps it would feel more possible to move the goalposts of the discourse beyond naming the persistence of racial discrimination toward a critique of enduring colonial control.

The ascendance of the liberal understanding of apartheid was crystallized in the International Criminal Court’s 1998 definition, which subtly backed away from the anti-colonial core of the UN’s 1973 Convention. The ICC definition retains the characterization of apartheid as institutionalized racial domination, but ties it more narrowly to the perpetration of crimes against humanity, stripping away the emphasis on its entanglement with settler colonialism via issues of land, labor, and exploitation. According to this view, which is oriented around the logic of criminal law, apartheid can be remedied by pursuing individualized accountability for “inhumane acts” of direct physical violence. Criminal culpability here is reserved for individuals rather than states, and does not require any confrontation with the larger social and political structures of colonial conquest and material extraction that the apartheid regime has consolidated.

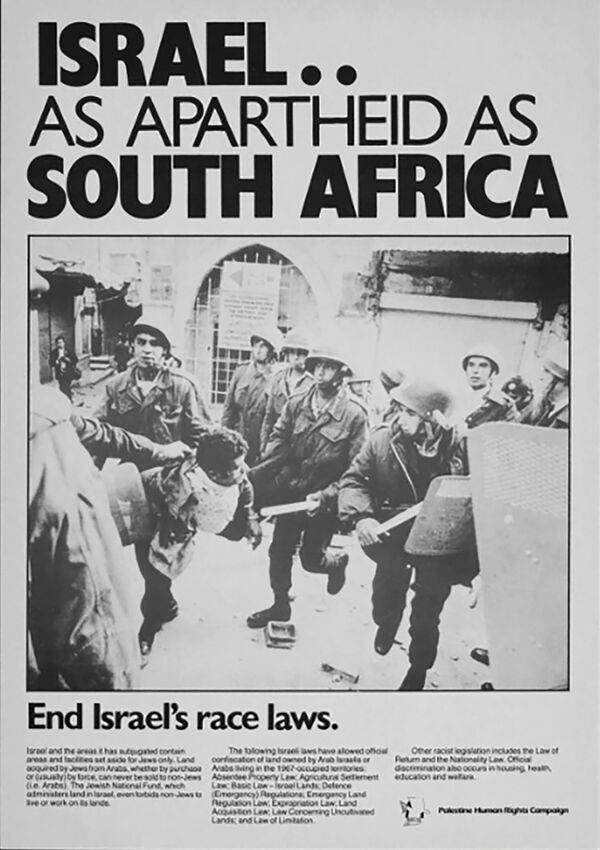

A poster by the Palestine Human Rights Campaign in 1982.

The rise of the liberal-legal analytical framework has had far-reaching material implications. In South Africa, legal scholar Christopher Gevers has written about the rise of an “international law myth,” which, among other analytical failures, misrepresents “the broad-based and ideologically multifaceted international struggle against apartheid [as] one for ‘civil and political rights,’” all the while “downplaying its more radical social and economic demands.” Quoting the South African philosopher Mogobe Ramose, he argues that this approach has resulted in a “formal vacuous justice” that “did not restore full, integral, and comprehensive and unencumbered sovereignty to the indigenous peoples conquered in the unjust wars of colonisation.” This emphasis on constitutional reform has shaped the post-apartheid transition, through which many structures of inequality have remained intact. Critical South African scholars like Tshepo Madlingozi call the present reality “neo-apartheid,” noting that a set of constitutional rearrangements have trapped Black South Africans in “a liminal state of unfreedom.”

In Palestine/Israel, likewise, political scientist Leila Farsakh has shown that the Oslo accords were pivotal to locking in the “Bantustanization” of Palestine—entrenching the fragmentation of the Palestinian territories while increasing their residents’ economic dependence on Israeli labor markets, co-opted Palestinian Authority institutions, and heavily conditioned aid, investment, and debt. Even if a political mobilization—or a campaign by human rights organizations—could pressure Israel to extend citizenship to all Palestinians in the occupied territories, and to apply Israeli civil and criminal law rather than military law to those citizens, the post-Oslo reality as it stands all but guarantees that Zionist institutions and Jewish settlers would keep hold of the land, privilege, and wealth that they have accrued through the conquest, dispossession, and exile of Palestinians. Even legislative reform to remove the legal pillars upholding Jewish supremacy—such as the 1950 Law of Return, which facilitates Zionist settlement by allowing any Jewish person to become an Israeli citizen, and the 2018 nation-state law, which re-enshrines and bolsters Israel’s constitutional identity as a state of the Jewish people—would not redress the racial and socioeconomic inequalities produced by the ghettoization of Palestinians and their exile from their original lands. Neo-apartheid in South Africa may serve as a cautionary tale: Proclaiming an end to apartheid without instituting a concrete program of decolonization in the form of land restitution and wealth redistribution may simply produce a more acceptable form of social, political, and economic discrimination.

Proclaiming an end to apartheid without instituting a concrete program of decolonization in the form of land restitution and wealth redistribution may simply produce a more acceptable form of social, political, and economic discrimination.

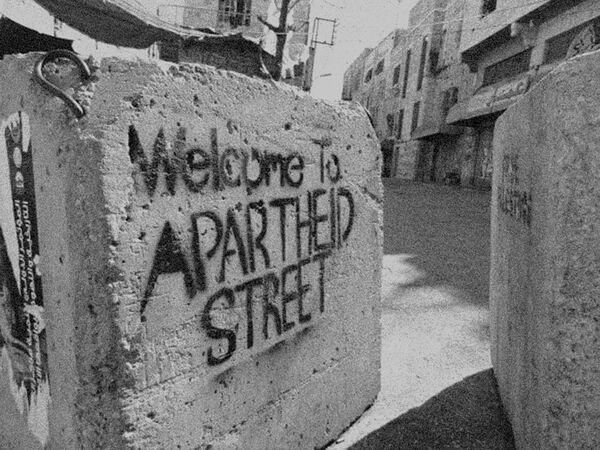

Graffiti on a barrier on Shuhada Street in the West Bank city of Hebron. The street is closed to Palestinians, but Israelis and foreign visitors are permitted entry.

To avoid the pitfalls of the liberal understanding of Israeli apartheid, we must grapple with Zionist ideology and institutions; only by doing so can we conceive of, and ultimately achieve, decolonization. Fortunately, even as legalistic understandings of apartheid eclipsed the radical critique advanced by Sayegh and his cohort, Palestinian intellectuals continued to analyze apartheid’s relationship to Zionism—most famous among them was Edward Said, a searing critic of the Oslo process whose writings on Palestine, from the 1970s until his death in 2003, were deeply engaged with the intellectual and institutional intersections of Zionsim, racism, apartheid, and imperialism. The subsequent generation of Palestinian scholars and activists who have revitalized the radical, decolonial critique that was largely abandoned by the Oslo generation are too many to list: Amneh Badran; Ali Abunimah; Raef Zreik; Adam Hanieh, Hazem Jamjoum, and Rafeef Ziadah; Nimer Sultany; Yasmeen Abu-Laban; Omar Barghouti; Samer Abdelnour; Ghada Ageel; Yara Hawari; Honaida Ghanim; Saree Makdisi; Mazen Masri; Hassan Jabareen; Lana Tatour; Rania Muhareb; Nahla Abdo; Tareq Baconi; Nadia Abu El-Haj; and Sherene Seikaly, among many, many others. It is their lead that critical and anti-Zionist Israeli and international scholars have followed. The current generation of thinkers and activists insist that they do not seek to simply democratize the settler colony—to offer liberal solutions in keeping with the liberal critique—but to decolonize it through an explicit disruption of Zionist claims and prerogatives: radical solutions to answer the radical critique.

Western human rights organizations’ acknowledgment that Israel oversees an apartheid regime constitutes a considerable step forward. The next step is to recognize the role of Zionism both in giving rise to apartheid and in perpetuating its practice: to consider Zionism’s ideological origins, its intellectual and political bedfellows across colonial geographies, its many victims, and its mounting and devastating costs.

Almost 50 years ago, Palestinian novelist and communist Emile Habiby closed his classic 1974 satire, The Secret Life of Saeed: The Pessoptimist, with the epilogue: “For the Sake of Truth and History.” The line reverberates through time. Today, Palestinian writer and activist Mohammed El-Kurd insists that naming things properly is essential to interpreting the world, and ultimately to changing it. It is significant that Palestinians have been naming and analyzing Israeli apartheid since at least the 1960s, and it is vital that we acknowledge and learn from their work. “Not for the sake of representation,” as El-Kurd puts it, “but for the sake of truth.”

Noura Erakat is an associate professor in the Department of Africana Studies and the Program in Criminal Justice at Rutgers, New Brunswick. She is the author of Justice for Some: Law and the Question of Palestine (2019).

John Reynolds teaches at the National University of Ireland, Maynooth. He is the author of Empire, Emergency and International Law (Cambridge University Press) and an editor of the Third World Approaches to International Law Review journal and website.