Portraits of Encounter

In paintings of Queens’s blue-collar workers and immigrant communities, Aliza Nisenbaum explores the small-scale politics of interpersonal relationships.

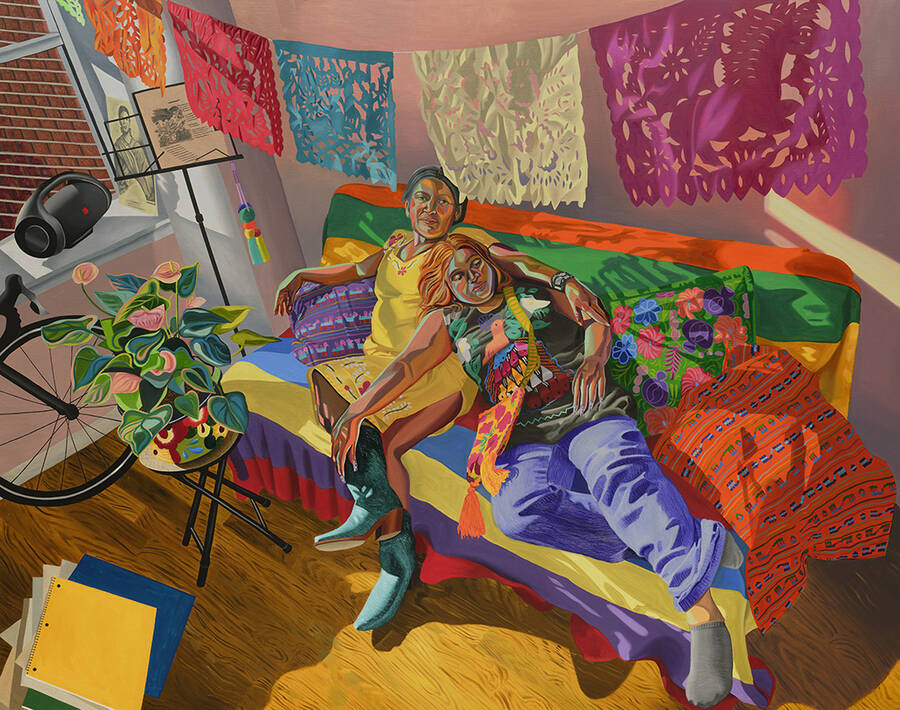

Pedacito de Sol (Vero y Marissa), 2022, oil on canvas, 75 x 95 in. Courtesy of the artist and Anton Kern Gallery, New York.

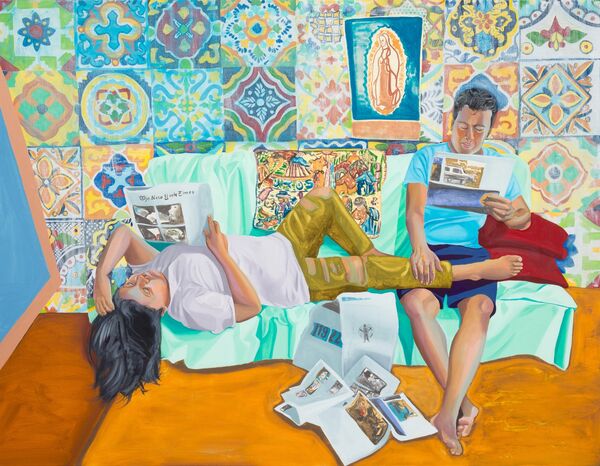

The first gallery in Aliza Nisenbaum’s exhibition at the Queens Museum is bookended by a pair of paintings that create an echo. At one end hangs La Talaverita, Sunday Morning NY Times (2016), in which a teenage girl and her father read the paper on a couch. Each one is absorbed in a different section of newsprint, but they’re linked at the point where the girl, who lies with her hair draped off the side of the couch, lays one of her legs across her father’s lap. He rests a hand on it. The wall behind them is covered with Mexican talavera tiles, whose loud patterns provide a counterpoint to the pair’s quiet concentration and easy affection.

Directly across the museum gallery hangs Pedacito de Sol (Vero y Marissa) (2022), which shows a woman and her daughter lazing on a couch in a sun-drenched room. Here the space is more defined, delineated by a boombox on the windowsill, a plant, and part of a bike. The two women nestle comfortably, their limbs overlapping, melding with each other and their surroundings so that the room comes to seem like its own ecosystem. The mother looks out at the viewer with a slight smile, while the daughter stares into space, lost in her own thoughts.

These paintings, made six years apart, depict the same young woman on the same couch. Her name is Marissa, and her home is in Corona, Queens, although by the time of the later work, she was just visiting on a college break. Nisenbaum began painting members of Corona’s Latin American community in 2012, when Marissa was ten years old. More than a decade later, the artist’s depictions of people who live and work in the neighborhood are at the center of her first solo museum show in New York City, the culmination of a two-year residency at the Queens Museum. The exhibition’s subtitle is “Queens, Lindo y Querido,” or “Queens, Beautiful and Beloved”—a phrase borrowed from the title of a popular song by the Mexican ranchera king Vicente Fernández. It’s a small show—just two rooms—that feels intimate, like a gathering of overlapping communities. Individual portraits are interspersed with paintings of duos and groups, creating a dynamic sense of interconnection, of exploring what it means to be both alone and together.

Aliza Nisenbaum: La Talaverita, Sunday Morning NY Times, 2016, oil on linen, 68 x 88 in. Courtesy of the artist and Anton Kern Gallery, New York.

Nisenbaum’s work is emblematic of the much-discussed renaissance of figurative painting, which has been underway for the better part of a decade. Portraiture, in particular, is often understood today as a process of representation and inclusion, a correction of the largely white, upper-class record. Since 2017, when five of her pieces, including La Talaverita, were shown in the Whitney Biennial, writers have pegged Nisenbaum—who was born in Mexico City—as a painter of immigrants. “The best portrait painters working today introduce something new into art not through stylistic innovations, but by whom they choose as subjects,” Dushko Petrovich wrote in an article that discusses Nisenbaum’s work published in T Magazine in 2018. Certainly, there’s gratification in seeing marginalized people get the kind of sumptuous treatment they receive in Nisenbaum’s paintings. But reading Nisenbaum primarily through the lens of representation elides important aspects of her practice—for example, she paints dancers and flowers, and she gets as animated about color as she does about her subjects. Above all, this emphasis might oversimplify the agenda of someone who’s more interested in the small-scale politics of interpersonal relationships than she is in societal or institutional critique.

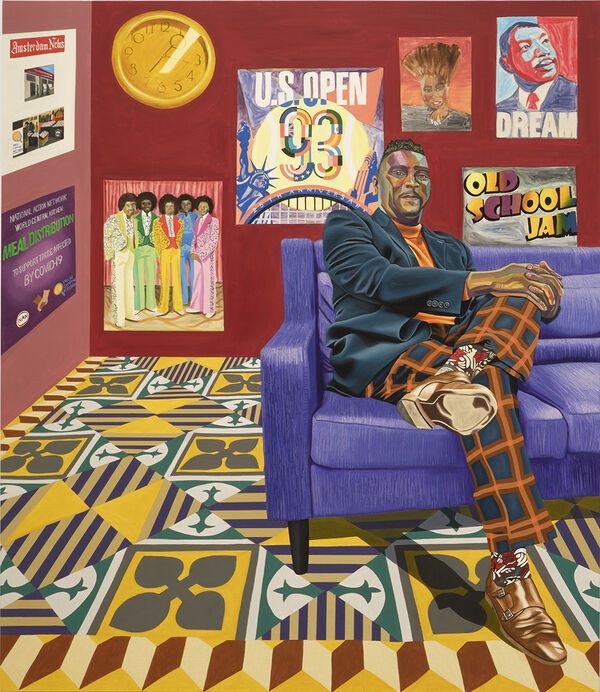

Indeed, even Nisenbaum’s most overtly political pieces—such as her group portraits of workers in places like airports, subway lines, and hospitals—tend to feel less like pronouncements than opportunities to consider our web of relation. Portraiture gives Nisenbaum a framework in which to encounter other people. In this she’s like the artist Alice Neel, who famously canonized friends, neighbors, and art-world figures in portraits so penetrating, they can be uncomfortable to look at. Neel called herself a “collector of souls”; Nisenbaum, by contrast, seems less interested in baring people’s true selves on canvas than in capturing something of their profound unknowability. Her subjects are often lost in thought or activity, like Marissa in La Talaverita and Pedacito de Sol. Others are immersed in settings filled with material culture—like Andra, a facilities staffer at the Queens Museum whom Nisenbaum depicts in his office, surrounded by posters and objects. Andra’s checkered pants and floral socks are echoed by the patterned rug beneath his feet, and the overall effect is a feeling that we, the viewers, are getting just a glimpse of the private world he inhabits.

Andra, 2022, oil on canvas, 73 1/8 x 63 in. Collection Glenn and Amanda Fuhrman, NY. Courtesy the FLAG Art Foundation.

If portraiture-as-representation is about bringing different faces to light, Nisenbaum deviates from the script by allowing her subjects to hold onto a bit of metaphorical shadow. We see them in colors so vivid, they sometimes seem to glow, but that doesn’t mean we can fully access them. “Vision is something that places distance,” Nisenbaum told me. At the same time, “painting is all about touch, and touch is always about being in relation. You can’t separate yourself from the situation.” In other words, as in any intimate relationship, there’s a push-pull in the act of rendering someone. Nisenbaum’s paintings draw us in, only to make us aware of how much we can’t know.

Nisenbaum grew up in the Santa Fe neighborhood of Mexico City, the daughter of a Russian Jewish father and a Norwegian American mother. Her father owned a factory that produced leather goods, and her mother painted flowers, buying bunches from the city’s famed markets to use as subjects. “She’d stuff her car with plants and then paint them at our house, and we would have critiques of her work over dinner,” Nisenbaum said. The city around her was also brimming with art, including the many products of the Mexican muralism movement that began in the 1920s. Artists like Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros painted big, nationalist, and often ardently socialist murals on publicly accessible walls, leaving behind iconic works that helped define the landscape of Nisenbaum’s childhood.

From an early age, she was interested in human behavior: Social work intrigued her, and she went to the Universidad Iberoamericana to study psychology before transferring to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), where she would go on to earn both a BFA and an MFA. As an undergraduate, Nisenbaum trained traditionally in figuration, but in graduate school she became interested in abstraction, inspired in part by professors like Michelle Grabner, whose work isolates objects and patterns from domestic life, such as the checkered lids of jam jars. She loved the mid-20th-century color field painters, especially Barnett Newman, who cut through his big, monochrome canvases with thin, vertical bands of color that he called “zips.” She was thinking, too, about politics, thanks to her professor Gregg Bordowitz, an artist and AIDS activist who would say, “The only politics that count are the ones in this room, right now,” as she recalled in an 2019 interview with The Brooklyn Rail. That emphasis on relationships and power dovetailed with what she learned from her sister, who was studying philosophy at the University of Chicago, about the Lithuanian-born Jew and French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas. Levinas wrote that our responsibility to others stems from our encounters with them—that all ethics “comes from the face-to-face relationship,” as Nisenbaum puts it—a concept that would soon inform how she engaged with the people she painted. But at the time, she struggled to synthesize all these ideas and influences into her work. “It was frustrating,” she once told the online magazine Artsy. “I was making paintings that wanted to have all these ideas, but they were abstract.”

Nisenbaum has been influenced by the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, who wrote that our responsibility to others stems from our encounters with them.

A few years after graduating, she moved to New York City, where she began teaching drawing at LaGuardia Community College in Queens. In her small studio, she began to dabble in figuration again by making paintings of flowers—a nod to her mother and her hometown. Her breakthrough came in 2012, when she began volunteering in Corona, at Immigrant Movement International (IMI). Founded by the artist and activist Tania Bruguera, IMI was an art project, community space, and advocacy organization, with storefront headquarters that connected immigrants in the neighborhood to legal and medical services, as well as offering classes, workshops, and cultural events. Tasked with helping members of the local Spanish-speaking community learn English, Nisenbaum put together a class called English Through Feminist Art History, in which she and the mostly women who enrolled translated texts and went to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to talk about whatever caught their eye.

The class sparked relationships that Nisenbaum wanted to deepen. She decided to set up an easel at IMI and paint the women’s portraits. As she did, her project expanded and evolved: She got to know her subjects, invited them over for meals, painted their husbands and families. The ideas she’d been thinking about since graduate school started to coalesce into a practice that was simultaneously conceptual and material—one grounded in the slow, intimate process of rendering someone’s likeness. She also developed a policy of compensating sitters. Before she was selling her work, she would cook for them and give them their finished paintings. (These small gestures of care sometimes yielded significant results; during the Covid-19 pandemic, when they were struggling with unemployment, Marissa and her mother were able to sell two early Nisenbaum pieces to Anton Kern Gallery, which represents the artist.) Now that there is a market for her work, Nisenbaum pays her subjects, and donates to organizations that are somehow aligned with the people she’s depicting in a given project. In the case of the current exhibition, that’s the La Jornada and Queens Museum Cultural Food Pantry, which takes place at the museum every Wednesday.

Such practices build on Levinas’s idea of an ethics grounded in the face-to-face encounter. In the process, they help Nisenbaum mitigate the exploitation that has been a hallmark of art history, especially when the people being portrayed come from groups on the margins of society. But beyond payment, Nisenbaum is interested in mutual relationships as both a standard and a subject. For example, the exhibition includes a large painting of the pantry titled Eloina, Angie, Abril y Marleny, Despensa de Alimentos, Queens Museum (2023). It’s a vertiginous scene of flattened perspective in which produce, volunteers, and “shoppers” form a sweeping, colorful loop of activity. A similar circular motion animates El Taller, Queens Museum (2023), a depiction of the free painting workshop that Nisenbaum led for local community members as part of her residency. In the piece, students sit around an arcing blue table, working on self-portraits in various states of completion. Neither image features a leader or authority figure; the groups seem instead to be self-sustaining, propelled by the energy of their activities.

In El Taller, each student appears immersed in their own project; several use mirrors to study their faces, with their backs turned to the viewer—perhaps the most literal expression to date of Nisenbaum’s impulse to privilege her subjects’ interiority over her audience’s access to them. And yet, we do get to know Nisenbaum’s students through their paintings, because the results of the workshop are also on view in the exhibition: self-portraits and depictions of subjects ranging from a tired clown to a glass of ponche, a Mexican Christmas punch. At the end of the day, it’s still Nisenbaum’s show, but the interaction between the painting of the workshop itself and the paintings produced in it points to her belief that art offers the possibility of agency. The students in El Taller become more than just subjects in someone else’s work; they get to imagine and create visions of their own.

Left: Eloina, Angie, Emma, Abril y Marleny, Despensa de Alimentos, Queens Museum, 2023, oil on canvas, 95 x 150 in. Courtesy of the artist and Anton Kern Gallery, New York.

Right: El Taller, Queens Museum, 2023, oil on canvas, 95 x 150 in. Courtesy of the artist and Anton Kern Gallery, New York.

Nisenbaum’s residency at the Queens Museum began with a commission to make a mural for LaGuardia Airport; the painting on which the mural will be based, The Ones who Make it Run (Delta Terminal C, LaGuardia Airport) (2022), is on view in the current show. Stretching over 17 feet long, it features 16 workers who hold a variety of jobs in the terminal, from pilot to wheelchair attendant. They’re arrayed in a kind of frieze, less a cohesive unit than a diverse pantheon, with each person standing or sitting several inches from the next. They appear at ease: Many of them look out at the viewer with slight, almost mysterious smiles as the sun shines through the windows behind them.

This isn’t the first time Nisenbaum has created a mural focused on a group of workers; she’s also painted British emergency room staffers at a children’s hospital during the Covid-19 pandemic; people employed by London’s transit agency, on the Underground’s Victoria line; and security guards at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, among others. This practice places her in dialogue with the Mexican muralists of her childhood, but the relationship is complicated. Rivera and his cohort had an overt political agenda. They were, by and large, Communists with staunch nationalist commitments, and their paintings glorified and strove to uplift the Mexican working class. Often, their murals attempted to dramatize the sweep of history with a symbolic vocabulary: romantic depictions of Indigenous peoples, men breaking free from chains of bondage, and masses marching toward revolution.

The Ones who Make it Run (Delta Terminal C, LaGuardia Airport), 2022, oil on canvas, 80 x 208 in. Courtesy the artist and Anton Kern Gallery, New York.

By contrast, Nisenbaum’s labor murals are almost oddly peaceful and still, despite their bright, eye-catching colors. Her workers stand and sit in loosely gathered groups. They don’t visibly toil or suffer; they’re not presented as allegories for the ills of capitalism. They are people whose labor is often overlooked or ignored, and Nisenbaum honors that by depicting them at work. Yet she also gives them the dignity of rest. As the critic Rachel Wetzler wrote in Art in America in 2020, “Though framed by the workplace, they are depicted in moments of respite or nonwork, if not necessarily leisure: the emphasis isn’t on the job, but the people who perform it.” The effect is less a paean to solidarity than a reflection on more personal forms of camaraderie.

When I asked Nisenbaum about her influences, she mentioned her appreciation for the Mexican muralists, but also for their female contemporaries: lesser-known artists like María Izquierdo and Olga Costa, who often painted portraits and domestic scenes like still lifes. Their approach was political in its own right—both were known for depicting the social struggles of women with radical honesty—but their inspiration wasn’t so much wide-scale class struggle as the closer terrain of personal experience. Nisenbaum’s murals evince a similar emphasis. They emerge from a process that involves hours spent getting to know her subjects, both one-on-one and in groups, and painting them individually as she assembles her compositions. “Sometimes, when I paint a group portrait, new alliances and friendships happen,” she said. “It’s an experiment in putting people together, like a staging of some sort.”

As this suggests, there is a theatricality to all of Nisenbaum’s work, especially her murals. A feeling of contingency hangs over them, a sense of fleeting harmony, suggesting that we’re glimpsing a moment that couldn’t last, even if it had once existed. Somehow, with their careful arrangements and luminous color, the murals capture something essential about both relationships and politics: how we come together to build something bigger than ourselves, and then, all too quickly, how we come apart.

Jillian Steinhauer writes about the politics of art and comics for publications like The New York Times, New York Magazine, The Nation, and The New Republic. She was a recipient of a 2019 Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant.