In the Hole

Five incarcerated men on the minute-by-minute experience of solitary confinement.

In 1829, at Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary, commonly known as Cherry Hill, descendants of Pennsylvania’s Quaker founders conceived the barbaric practice of isolating humans in cold concrete cells, the first experiment in a punitive practice now known as “solitary confinement.” They thought that isolation might sever those subjected to it from their deviant behaviors by giving them time to reflect, study, and pray. Cherry Hill’s administrators learned almost immediately that the practice did not reform men but instead drove them crazy. In 1842, upon visiting Cherry Hill, Charles Dickens said, “I believe that very few men are capable of estimating the immense amount of torture and agony which this dreadful punishment, prolonged for years, inflicts upon the sufferers.”

Yet today, solitary confinement persists as a common tactic in US prisons. It can be difficult to get an accurate sense of just how widespread this practice is, due to shortcomings in available data. But the numbers we do have are staggering. The most recent prison census, released in 2021 by Bureau of Justice Statistics, found that more than 75,000 people were being held in solitary confinement—defined as being confined to the cell for 22 hours a day—when the census was taken in 2019. (These numbers included state and federal prisons but not jails—which hold people awaiting trial or serving some short sentences—likely making the real number much higher.) A more recent study, released in 2022 and co-authored by the Correctional Leaders Association and the Arthur Liman Center for Public Interest Law at Yale Law School, suggested that the number of people held in solitary seemed to have declined to roughly 41,000–48,000 when they collected their numbers in July 2021. But clearly, tens of thousands of incarcerated people are still regularly forced to endure the grueling experience of solitary almost 200 years after it proved to be a failed experiment. The consequences are devastating: Just last week, newly released footage from an Indiana jail showed that 29-year-old Joshua McLemore died of malnutrition there during a schizophrenic episode in summer 2021 after being left in solitary confinement for 20 days without mental health treatment.

After spending years of my life caged in solitary confinement, beginning at age 12, I felt the stories of those subjected to solitary had to be shared. So I encouraged participants in the writer development program I created at the prison where I live in Washington State to write about it, with each of them examining different aspects of the experience. Our narrative takes you chronologically from the moment of being taken away to solitary, to the slog of bearing the isolation itself, to the aftermath of seeking healing amid persistent trauma. All of the men who participated in this piece have spent portions of their lives, some short and some long-lasting, in solitary confinement, some as adolescents and others as young adults. All of them have experienced life-altering moments while trapped behind that thick steel door. The process of constructing these short stories left each of the men in a troubled state, forced to dredge up some of the bleakest moments of their lives—times where feelings of hope, belonging, and love were pushed deep down and walled up, while feelings of depression and loneliness reigned. But they wanted to write about it anyway. Only through sharing our stories and educating the public can we work to end the practice that caused us all this harm.

– Christopher Blackwell

Before Solitary | Day One of Solitary | The Endless Middle | Juvenile in Solitary | Last Day of Solitary | After Solitary | Solitary’s Long Shadow

Aaron Edward Olson

“Cuff up!” demanded a raspy baritone voice. The eight member goon squad of guards clad in riot gear, fit with shock shields and batons, crowded outside my cell door in battle formation. I sat up on the cold steel bunk, slid into state-issued foam sandals, and shuffled over to my new nemesis. “Name’s Parkinson,” growled the lead guard, “like the disease! This is a cell extraction!” he barked. A glob of chewing tobacco hung from a front tooth, one of the few yellow survivors of a hard life.

Before this rude interruption, life at Stafford Creek Correctional Center in Washington State, where I had arrived 11 months earlier, seemed to be looking up after an awful start. I’d been attacked the day I arrived by another prisoner who had stopped taking his court ordered meds, and the brutal prison gossip mill had been passing around information on my criminal history, earning me derogatory nicknames. But now, my reputation was beginning to rebound, as more prisoners got to know me. Since the attack, I had been required to meet weekly with a mental health counselor—an elderly man with a long, silver beard whom I privately nicknamed Santa—and though he sometimes acted temperamental and angry with me for reasons I couldn’t understand, we’d just had our best appointment yet. On Super Bowl Sunday, the prison hosted an event selling pizzas to fundraise for veterans—a rare perk in an otherwise gloomy place. I splurged and bought a soda and large pizza. I’d have savored it more had I known what lay ahead.

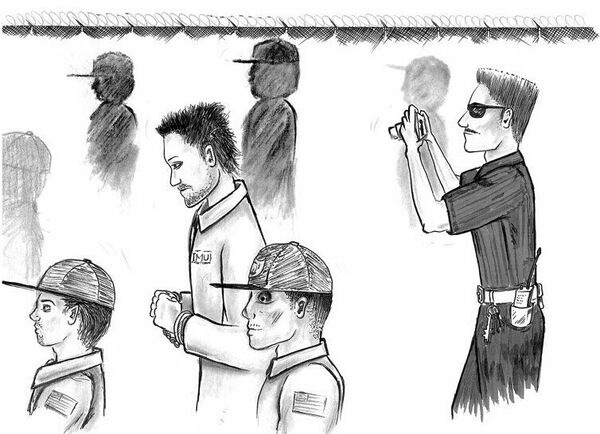

Being escorted from my cell in cuffs was humiliating. When I opened my cell door, the goon squad recoiled, all eight guards tensing into a slight crouch. “Face the wall, and stand for search!” barked the Disease. He leaned on my back with one forearm, his gut pushing against my waistline as he patted my side and legs. I could smell his body odor, a mix of stale tobacco, coffee, and tooth decay that he attempted to cover up with cheap aftershave. This was turning into a spectacle, with 120 men watching from the day room. Even though many of these men have endured similar cell extractions for various reasons, their faces said exactly what I would be thinking if the roles were reversed: What did he do? I was asking myself the same question, racking my memory for anything that made sense. As a prisoner, you are conditioned to believe you’ve done something wrong, but I could think of nothing. My routine was simple: work, school, exercise, and church. That was it.

It was a half-mile walk to solitary confinement, stretching almost the entire length of the compound from my living unit. One guard led the parade, with another in the back, holding a video camera. I was flanked by six others, three on each side. They could have just asked me to report to solitary, and I would have complied, knowing that refusal would only get me pepper-sprayed, gang-tackled, and tased. But the message intended by my perp walk was clear: We can crush you whenever we want.

Solitary confinement has many names: Officially it’s the SHU (Segregated Housing Unit) or IMU (Intensive Management Unit), but it’s also called The Hole or Iso or Lock-Up, among other unsavory terms. At this prison, The Hole was an entirely separate unit, and housed over 200 prisoners. As if the prison’s gun towers, razor wire, attack dogs, and army of guards is not enough, the process of entering the Hole involves passing through another set of sliding gates, and then half a dozen or more doors that must be buzzed open from some distant control booth.

I was placed in a holding cell, and told to strip naked as two guards I had never seen before stared at me, visibly irritated at my hesitation. First I had to open my mouth, swipe my gums, and wiggle my tongue, then hold my arms high, lift my testicles, spread my butt cheeks, and show the bottoms of my feet. I felt numb; it was hard to think. Only one thought kept piercing my delirium: This is your life.

The steel door slammed shut, and I entered my new home: a six-by-eight-foot concrete box, with none of my books, clothes, or basic personal items to soften the hard steel and concrete. The drab room, barely bigger than a closet, held a steel bunk on a bare concrete floor. The toilet was a hunk of metal, a hole, with no lid. The cell was musty, with wafts of mildew and urine.

I would wait there in suspense for the next ten days before I received a hearing. That day, I was ushered into the court by two guards; I wore a bright orange jumpsuit, belly chains, wrist cuffs, and leg irons, and a chain that swept the floor with every step. My attire could not hope to inspire an unbiased verdict. “Do you know why you are here?” asked the hearings officer. “No,” I replied. He proceeded to read a report and formal accusation: “Inmate Olson has become fixated on a female staff member, and exhibited predatory behavior.”

I was stunned. I scanned the room, seeing eyes of disgust and contempt. I was scum to them, and surely guilty of the accusation. I cleared my throat, and mustered a plea to every person present. “Please, investigate this. This is not true. I would never do this,” I said. “That’s not what your criminal history suggests,” smirked the case manager—the man appointed to advocate for my best interest.

When you’ve been guilty of something before, it’s not hard to believe you’ve done it again. The accusation had come from “Santa,” my mental health counselor, who now recommended I be referred for a six-month Intensive Management Unit (IMU) program, which included a facility separation requirement, meaning I had to serve the solitary time at a different prison and could never return to Stafford Creek. (I learned only much later, after I got legal help to investigate the charges, that Santa’s animosity toward me appeared rooted in his disagreements with other staff members over how best to treat me; I was a casualty of longstanding office politics.) I had thought he was trying to help me. Instead, he acted as an agent of modern slavery, an administrator of the plantation where I was being kept. He punished me for my past, and crippled my hope for the future.

Though Santa’s accusation was recorded in a note on my permanent record—meaning I am still dealing with the consequences over a decade later—I received no official infraction, and therefore no option to appeal. No accusation was ever made against me by any female staff member. Yet I was still sentenced to eight months in solitary confinement. So much for mental health treatment. The dark, cold, lonely concrete walls of isolation was my counselor’s “prescription.” With the judgment decreed, I was escorted back to my solitary cell, where I spent the next 50 days, until being transferred to another facility several hours away for another six months in the hole.

Antoine Davis

Boom, boom, boom! The loud noise echoed down the hallway as the two prison guards escorted me to the cell I had been assigned. It was a summer afternoon, and the sunlight coming through the gray-coated windows reminded me of the freedoms I couldn’t reach. The oversized orange jumpsuit draped over my body felt like a metaphor: This place didn’t fit; I didn’t belong there. As we moved past one cell door after another, I could feel the eyes of some of the men watching me through plexiglass windows behind paint-chipped bars. Solitary confinement felt like a place for animals.

I winced as the guards sped up, causing the steel cuffs to bite into the back of my ankles. As we passed another cell, a strong whiff of urine made me nauseous. “How long am I supposed to be here?” I asked the guard. “Don’t know—it depends,” he responded.

Boom, boom, boom! Somewhere toward the end of the tier, the stranger responsible for the noise kept pounding on what I later learned was the cell’s toilet. The man burst into maniacal laughter as if he had accomplished something he’d been working on for decades. The cell door in front of me slid open and the guard to my right tightened his grip to steady me. The other guard bent down to remove the cuffs from my feet before tapping my back as a signal for me to step in. With a humming sound the cell door slid closed and locked with a loud clank.

“Hey there’s no mattress in here!” I yelled. “We’ll get you one when we have time,” a guard snapped back. I let out a sigh, trying not to let my frustrations get the best of me. I’d never been in the hole before. I observed the room. The bunk was coated in dust and pieces of dry food. The corners of the frame were rusted. The walls were covered with gang-related and racist writings, including a drawing of a woman with swastikas all over her body.

Within 30 minutes the cell door slid open again and the guard handed me an old mattress. I tossed the plastic mat onto the steel bunk, in utter disbelief that I was to sleep on something so unsanitary. I asked for something to wipe down the bedding with, but the guard told me that cleaning supplies would have to wait. His tone implied I should be grateful for having anything to sleep on at all. When the cell door closed again, I stood there for a moment, leaning against the wall, wondering how many bodies this mattress had been subjected to. It was deflated. The cotton inside puffed through the countless cracks that lined it from top to bottom. The sheets and blankets were hardly in better condition.

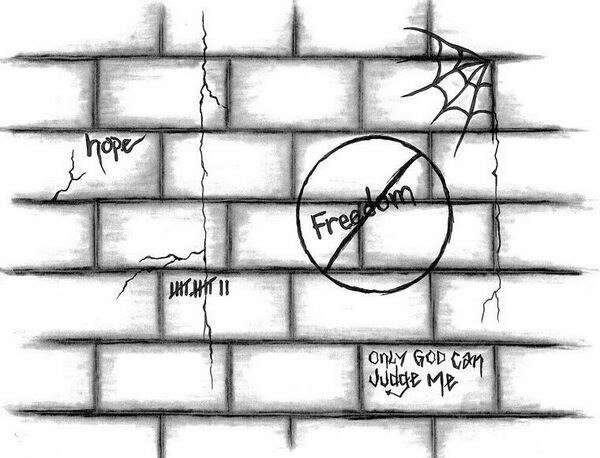

I wanted to cry. Left to myself, trapped in the filthy little cage, I had the perfect opportunity to do so. No one would know; no one would see; no one would hear. It was then that I realized that solitary confinement is designed to break our spirits. It’s an excuse for the system to treat us the way it truly sees us, unworthy of human dignity and unfit for society. If the following days were anything like today, this would be one of the lowest moments of my entire life.

Aaron Edward Olson

From the outside, the transport bus that carried me from one solitary unit to another at a different facility resembled a Greyhound, but the seats were hard plastic. In the back, in the place of where a seat would be, there was an open toilet that sloshed on every bump, filling the air with the pungent scent of urinal cake and pounds of ripe excrement. I was one of 40 prisoners wearing an orange jumpsuit, belly chains, wrists cuffed to the waist, and leg irons. None of us had seat belts. When I arrived at my new destination, it looked exactly like the Segregation Unit I had just left: another prison within a prison. Did they just drive in a big circle? I wondered.

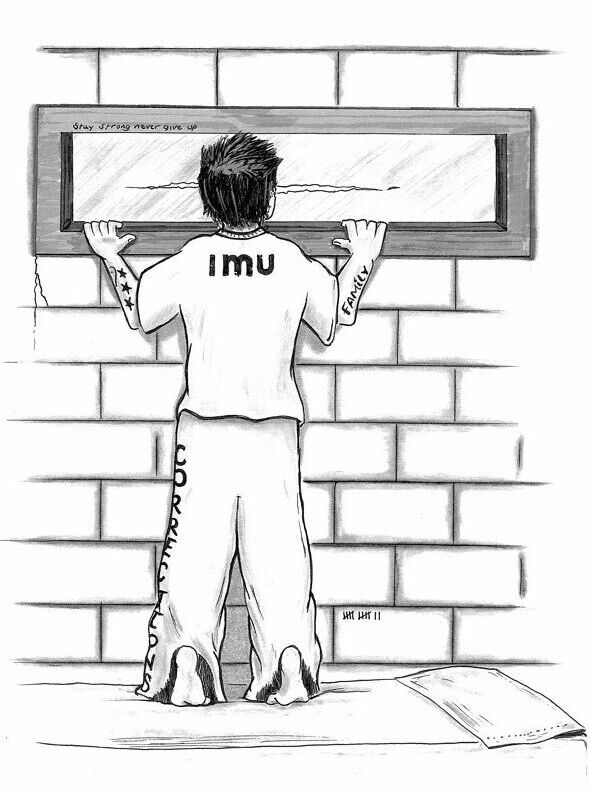

As I settled into my new cell, lunch arrived, according to the typical solitary mealtime process: The guard screams “mainline!” and if you’re not standing on a yellow line near the door as the meal cart goes by, it keeps going. Food portions were small, and I remained hungry from one tray to the next, waiting for my next meal like a starved dog in a kennel. One bright spot was that my window was not completely blacked out. A thick, long scratch in the exterior latex coating offered a glimpse of a different reality. Standing on tiptoes on my bunk, I could make out people walking to and from their cars in a distant parking lot. I imagined what their lives were like, and if they even knew I existed. Hours would pass, and my toes went numb.

Human contact was sparse. Each week offered five one-hour sessions of recreation, and three ten-minute opportunities to shower. I was placed on a leash by the guards and walked like a dog to my destination. Before the leash could be attached, I had to squat awkwardly, extending my arms straight back through the food port in the center of the door so they could handcuff me from the outside. Before escorting me to or from my cell, the two-man team would perform a dehumanizing strip search. “Show me the nasty,” they’d say, laughing.

Recreation involved being taken to another concrete box called “the yard,” which, despite its name, had no grass. The ’80s style payphone housed in a crude steel cage by the door was our only means of contacting the outside world. I spent most of my hour on the phone, or sometimes doing a few pull ups on a bar in the yard. All year round, an old dirty jacket lay on the ground, for use by all in case it got cold. A small mesh grate in the top corner of the room provided a peek at the sky, where I hoped to see a plane or bird. I never did. Occasionally, instead of recreation time, I might have a one-hour visit with my mom and little sister, separated by glass.

The screams and rants of other prisoners echoed into the night, accompanied by the pounding on their steel doors. Walkie-talkies crackled, keys jingled, a fluorescent light that never went dark hummed incessantly, and more and more often, I thought of killing myself. Maybe I was already dead and this was hell, I thought. At some point, I don’t remember when, I realized I needed a routine to stay alive and sane. So I created one. I woke up to guards slamming steel trap doors and yelling several pods away, giving me a 10-to 15-minute head start on a workout: pushups and sit-ups one day, and squats and calf raises the next. Afterwards, I would read the Bible, one of only two books allowed in my cell. I spent the next several hours writing, recording my dreams, ambitions, and thoughts, and periodically stretching. After lunch I would read the second book, a novel, which I got to switch out once a week: I usually picked a western, sometimes sci-fi if I felt like taking a risk. As I read, some men played chess from cell to cell, yelling the piece and space number back-and-forth. After recreation time, I spent my evenings with a disappointing dinner and my book. Then, I tried to sleep under the fluorescent lights.

My family doesn’t understand when I explain that my memories of that time are blurred. They have months or years of distinct memories. In solitary, I only had one. Each day was the same, and began with the worst part: waking up. “Nothing” happens each moment of every day. Yet in those moments of nothingness, the absence of life, happiness, and experience gives birth to misery and despair—the torture of knowing that your life is worth nothing, that it holds nothing: no casual conversations with a neighbor or coworker, no hugs from friends and family, no kisses from a spouse. There is nothing left but bare survival.

Raymond Williams

The door slammed behind me. I looked across the room in confusion. This wasn’t a cell; it couldn’t be. There was no bed, no sink, and no toilet. There was a mattress thrown on the ground at the far end of the cell. And there was a smell. Sewage?

I looked at the floor. It was different, covered in a rubbery material instead of the bare refined concrete I’d grown accustomed to in my cell. In the center of the room there was a barred grate over a hole in the floor. I realized with horror that the cell had a toilet after all. It was like something from medieval times.

There is no polite way to tell this story. Imagine defecating through that barred grate in the middle of a floor. As disgusting as you imagine it, it’s worse. Your waste doesn’t simply fall through. It rests on top of the grate leaving you with a choice no human should be forced to make: Take the small individual squares of toilet paper they give you and push the feces through the grate into the hole, or live with the stench and horror of a log sitting in the middle of your floor like some unholy shrine. If you choose the former, like I did, you will want to be extra careful not to get any on your fingers. There is no sink to wash with, and the squares of toilet paper are perilously thin. Do not worry too much about what’s left along the edges of the bars. Soon enough you will urinate, and if your aim is good enough, you can blast the remaining matter away.

This was solitary in the Thurston County Juvenile Detention Facility in Olympia Washington in the 1990s. I was 14 years old. I spent weeks at a time in that cell over the years of my youth. At the time, like other youth, I was seeking a sense of self, my place in the world and in society. The brutality of juvenile solitary diminished my self-worth, already fragile after an early childhood of abuse at home and in various foster placements. It set the stage for the adult I would become: #767974.

Christopher Blackwell

One day, around 8:00 pm, two guards finally came to my door. I was starting to lose hope that I was even getting out that day. As they looked in the tiny window, one of the guards asked if I was ready to be returned to mainline. I thought: What a stupid question. I didn’t say this out loud, for fear that they might change their minds and leave me trapped in the cold, dingy cell. “All my stuff is in the paper bag and I’m ready,” I told them.

The guards asked me to come to the door so I could be cuffed. You leave how you enter: tightly bound. One last reminder that they are in control. But I was just happy to be getting out. I would do what they wanted, willingly toss my humanity aside like an empty wrapper.

I was cuffed and brought to the solitary visit room, where I sat for a while. Finally, a guard arrived. He told me to strip; my body was inspected from top to bottom, not missing a crack or crevice. They had to make sure I didn’t take anything from the bare cell I had just left, as if there was anything to take. I got dressed and waited for an escort to take me back to the main prison. Twenty more minutes, then the escort arrived, and I was again cuffed tightly with my hands behind my back. The door opened and we proceeded through three sets of large steel doors. The last one exposed me to the fresh open air, crisp and inviting. Standing there, cuffed, in a bright orange jumpsuit many sizes too large, I pulled deep breaths into my lungs, as if the air would cease to exist at any moment. It felt like I hadn’t been outside for years, though it had only been weeks.

Still, the demonstration of power wasn’t over. Not long after we entered the open air, I was instructed by one of the guards to bend over and face the ground. Confused by this command, I ask the guard to repeat what he’d said. He repeated himself in a more aggressive tone, putting his large frame directly in front of me, eyes locked on mine. I quickly followed his directive. I was immediately surrounded by all three guards. Two of them placed their hands firmly on my back, making sure it was impossible to stand up straight. After a couple of minutes bent over like this, I was directed to return to an upright position. Unable to help myself, I asked why that was necessary. The guards told me not to worry about security procedures. I said nothing more.

We traveled through openings in a couple of towering fences laced with shiny razor wire. Everyone was quiet. All I could think about was how badly I wanted to be released from their company. Eventually, we came to a side gate, and I recognized the large concrete steps that led to the main prison. My heart started to race. This nightmare was finally about to end. I could go back to my regular program: school, visits, and phone time. I’d finally get a full night’s sleep.

We proceeded through the large gate; the cuffs were removed from my sore wrists, and I was instructed to return to my regular living unit. Just like that, I was released. I took the stairs two at a time, as if trying to escape capture. I had no clue why I was doing this, since the guards had no reason to grab me and return me to solitary. It just felt right to put as much distance between us as possible. My friends in the living unit were excited to see me. It felt good to see them. Some of these guys have been my friends for decades, and the reality is, in this world, when people go to solitary, they often never return. Friends simply disappear, and we’re left to wonder what happened—where they were sent, how much trouble they got in. All we have is rumors and speculation.

This time, though, I was lucky enough to return to where I‘d come from. As I settled in my cell that night, I took my shoes off and extended my legs across my bunk. The unit was silent: no screams from prisoners suffering from the isolation, no kicking of doors and yelling at taunting guards. I rolled over and quickly fell asleep.

Jonathan Kirkpatrick

I looked out my window. It was still early. I might have been able to see the sunrise, but my cell window didn’t have a view that far east; the trees were in the way. No one else was awake, only me. I had just been released from almost 18 months in solitary confinement.

Now that I was back in my general population unit, I was having a hard time sleeping. It wasn’t the noise; our tier was generally quiet. The problem was I was having a hard time winding down. The days were filled with so many sights and sounds that I wasn’t used to. When people tried to talk to me, I just heard meaningless babble, like the adults in a Charlie Brown cartoon. Everything seemed so large and oppressive: A walk to the chow hall was an ordeal that required the preparation of a road trip. I would lay in my bunk at night just trying to catch up with the day. A few minutes of conversation could take me hours to process, as I tried to figure out what everyone wanted. And so I couldn’t sleep.

In my mind, I knew I probably had some sort of post-traumatic stress disorder. A lot had happened: Two summers before, I had been brutally stabbed due to a gang conflict. My lung collapsed and my carotid artery nearly severed. I was airlifted from the remote prison in Clallam Bay on the northwest tip of Washington to Harborview Hospital in Seattle 100 miles away, where I underwent surgery. I spent the next year in solitary, which was the prison’s way of protecting me from my assailants. During that time I received no counseling to address what had happened to me, just dead time for my mind to race with negative thoughts. I spent all of that time nursing my grudge against the people who had stabbed me, promising myself some sort of retribution. Someone had to pay for the harm I suffered. When I returned back to the prison where I’d been attacked, I felt surrounded by enemies. As I sat up each night, looking out my window, I could sense that something was wrong with me, but I didn’t know how to fix it.

The high levels of stress began to take a toll; soon my body began to fail. I had been diagnosed with HIV in 1992. By 1999, before I was stabbed, my illness was under control, and I was in good health. I was no longer on any medications and I was physically fit. After almost a year in isolation, recovering from the stabbing wounds, my T-cell count began to drop. Medication stabilized me, but also came with frustrating side effects, like vomiting and headaches. Still, I strove to maintain a rigorous exercise regimen. By the time they released me from solitary, I was in excellent condition, given the circumstances.

But now, two weeks after leaving solitary, I had suddenly developed an extreme case of shingles, blanketing most of my body, and causing so much pain I had to be sedated with morphine. I began to lose weight at an alarming rate, ten pounds every few weeks. Prison health officials called it wasting disease. My muscle mass diminished and I came down with pneumonia, which seemed to fill my lungs with molasses. As each day passed and I became weaker, I felt more like the end was coming. Desperation and paranoia settled over me like a cloud that wouldn’t blow away. While I’d been unable to sleep just weeks ago, right after my release from solitary, now I could hardly find the energy to stay awake.

The doctors told me that I would be okay. They didn’t even keep me in the infirmary. I didn’t believe them. I was scared and tired and lonely. They tried to explain how stress could have a physical effect on the body. I followed the conversation but didn’t really understand at first. But when you can’t do anything else, sometimes the only thing left is self-reflection. I came to understand that I was killing myself—the hate I had spent so much time feeding on in solitary was now eating me from the inside out.

Raymond Williams

By age 17, I was out of juvie and in the adult prison system; I spent the year I turned 18 in solitary in the Washington Department of Corrections. When the guards placed me there, my first thought was how much nicer the cell was than the juvenile facility. I had a toilet, sink, a desk, a bed, and even a mirror. There was a small window looking outside. Everything was clean. But these impressions soon gave way to a colder reality, an isolation and loneliness no human being should taste.

It was hard to maintain sanity when the lights never shut off. I had a neighbor once who beat the metal toilet night after night with his sandal. Gong-gong-gong! All night long, night after night. Prisoners also banged on doors. I did too. Why? Stimulation. Attention. To prove I was alive. Three months into the madness I couldn’t sleep even on good days. I started hearing voices.

Six months in, the isolation and loneliness started to eat me. As a former foster youth, I had no family to call and no one to write me, and I grew desperate for support and friendship. When I gained access to a phone I started dialing random numbers collect. I hoped someone would answer and I would make a friend. But people rarely answered, and when they did, I didn’t find what I was looking for. Eventually I stopped calling out. I turned inward, and I have never been the same. I cannot forget the years in solitary I endured as a youth. I can’t shake the sense of loneliness that lingers to this day. The long term effects of solitary live on in me.

Christopher Blackwell is serving a 45-year prison sentence in Washington state. He is a contributing writer at Jewish Currents and contributing editor at The Appeal and works closely with Empowerment Avenue. He co-founded the organization Look2Justice.

Aaron Edward Olson is an author, journalist, and podcast host (listen at AaronEdwardOlson.com). Sentenced to life at age 19, Aaron chronicles 17 years of life behind bars and his hope for prison and sentencing reform.

Antoine Davis, 35, received his pastorate license at Freedom Church Of Seattle while incarcerated. He is a lead organizer of Look2Justice and co-chair of the Black Prisoners Caucus’s TEACH Program.

Raymond Williams is an incarcerated journalist who has spent over 20 years in Washington prisons.

Jonathan Kirkpatrick is an incarcerated writer at Washington Corrections Center. He does HIV/HCV harm reduction work inside.

Hector Ortiz is a Native American indigenous artist. He is deeply invested in his culture and is a seeker of life’s knowledge.