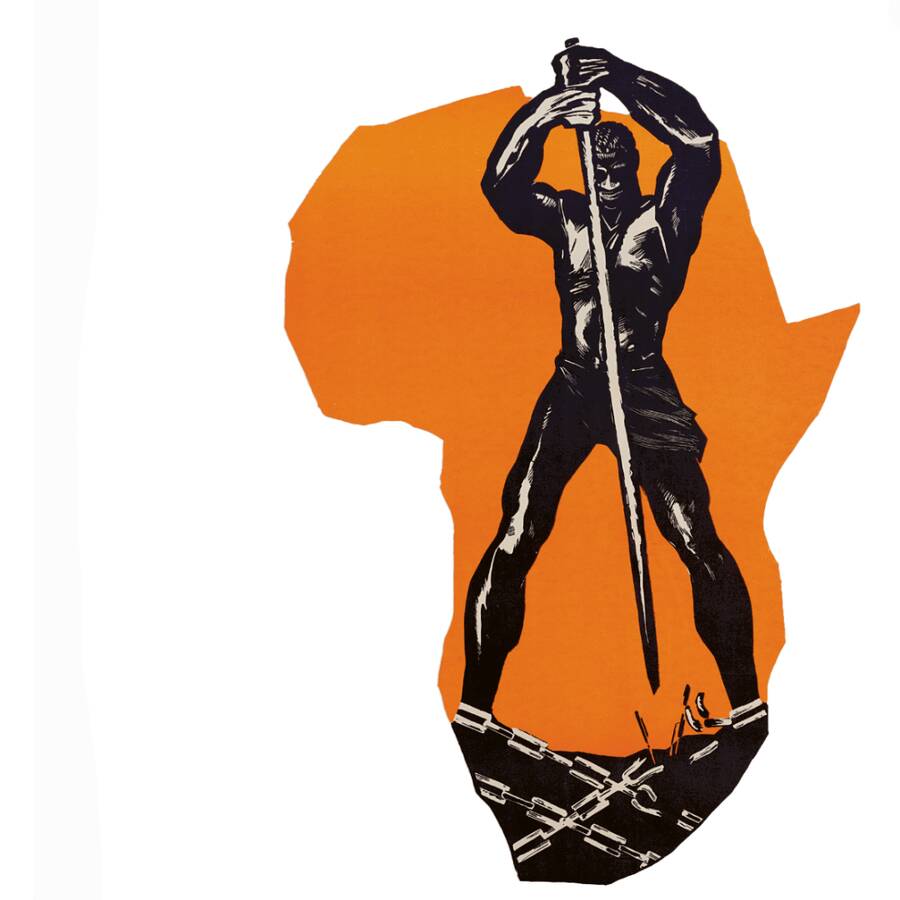

Art adapted from poster by Eduard Artsrunyan, 1966.

Discussed in this essay: The Wayland Rudd Collection, edited by Yevgeniy Fiks. Ugly Duckling Press, 2021. 264 pages.

THE MELODRAMATIC PLOT of the 1936 Soviet classic Circus revolves around a dark secret: The beautiful American circus artist Marion Dixon has a mixed-race Black son. Driven from her Jim Crow town, Dixon lives under threat of exposure by her dastardly German theatrical agent Franz von Kneischitz, who provides her a sinister refuge in his circus—and his bed—in exchange for his silence. The performer finds a real refuge only in the Soviet Union. There—unlike the racially segregated United States and von Kneischitz’s Nazi Germany, where moral panics around miscegenation eventually led to the sterilization of hundreds of Afro-German children—Dixon’s child is not a controversy. Instead, the entire circus audience, filled with people of various Soviet ethnicities, lovingly passes around the soothed and smiling child (played by James Patterson, himself the child of an African American immigrant to the Soviet Union and a Ukrainian theater actress) while singing a multilingual rendition of “The International Lullaby.” “In our country we love all kids,” the kindly state circus owner tells Dixon. The Soviet ethos, we are shown, is racial harmony.

Forty-nine years after Circus, the Hollywood dance drama White Nights was released. In it, a catastrophic plane crash brings together Nikolai Rodchenko (Mikhail Baryshnikov), a Soviet ballet dancer, and African American tap dancer Raymond Greenwood (Gregory Hines), who have defected to each other’s respective birthplaces. Initial conflicts stem from deep disillusionment with their countries of origin; Greenwood is especially disgusted by Rodchenko’s glorification of the United States. But the unfolding movie reveals that the Soviet project cannibalizes everything it purports to nurture, its native artists and political refugees alike. The two men and Greenwood’s pregnant wife successfully complete a tense escape from Leningrad and the stifling omnipresence of KGB surveillance. And despite his bitter recollection about the grinding racism in Harlem and the traumatic realization of his expendability as a US serviceman in Vietnam, Greenwood tearfully proclaims to his wife: “I’m going home. For better, for worse, I’m going home.” Anything, even the worst of American anti-blackness, is better than the Soviet Union.

The vexed memories of the relationship between the USSR and Black people as illustrated in both movies is at the center of The Wayland Rudd Collection, a new anthology edited by post-Soviet artist Yevgeniy Fiks. Based on a 2014 collaborative exhibition of the same name, the collection includes over 300 representations of Africans and African Americans in Soviet media—paintings, film stills, book illustrations, propaganda posters, stamps, figurines, and other ephemera—and the book assembles essays by scholars, writers, and artists examining these images and their political legacies. By setting fraught Soviet representations of blackness alongside analyses of contemporary writers and stories of Black people whose lives were bound up with the Soviet project (like MaryLouise Patterson, daughter of Communist Party USA leader William L. Patterson, and the famed actor and activist Paul Robeson), Fiks has compiled what he calls an “alternate archive of Soviet history” through which to “reflect upon and problematize the Soviet promise of universal equality.” Elsewhere, he has described his work as operating in a spirit of “critical nostalgia,” eschewing simplistic modes of condemnation or hagiography and instead attempting to “expos[e] repressed histories.”

For Fiks, the life and image of Wayland Rudd, a Black American actor who moved to and spent his adult life in the Soviet Union (and had an uncredited cameo in The Circus), exemplifies the need for such an approach. An up-and-coming theater actor from Lincoln, Nebraska—he was the first Black performer in the United States to be cast in the role of Othello—Rudd first visited Moscow in 1932 as part of a delegation of artists and performers, including Langston Hughes, who planned to make a film about American anti-blackness. The production failed to materialize, but Rudd stayed in the Soviet Union, working with theater director Vsevolod Meyerhold and playing a convict in Lev Kuleshov’s 1933 film The Great Consoler. In 1934, he returned to the United States with his white Russian wife and mixed-race daughter, flouting Jim Crow segregation to champion the multiracial Soviet productions in which he had featured at a time when blackface was still regularly used in lieu of Black actors. Rudd moved back to the Soviet Union permanently in 1936, finding success as an actor and playwright who, Fiks writes, “came to defin[e] in many respects the image of the ‘Negro’ for generations of Soviet people.” Rudd posed for paintings and propaganda images—his face is included in Viktor Koretsky’s 1937 poster in solidarity with the Soviet-supported Republican faction of the Spanish Civil War—and received full Soviet honors upon his death.

Poster by Viktor Koretsky depicting Wayland Rudd (second from the left) among a group of Soviet fighters, led by a Republican soldier in the Spanish Civil War, 1937.

Should we be celebratory or skeptical about a society that allowed Rudd to achieve a stature denied him in his country of origin, but perhaps also needed to circulate his image to conceal its own domestic failings on the front of racial justice?

What are we to make of Rudd’s legacy and his iconicity? Should we be celebratory or skeptical about a society that allowed Rudd to achieve a stature denied him in his country of origin, but perhaps also needed to circulate his image to conceal its own domestic failings on the front of racial justice—including, Fiks writes, “hypocrisy in the [Soviet Union’s] treatment of its own national minorities”? For Fiks, these questions are inevitably personal ones; in approaching them, he writes, “the Soviet believer in me was at odds with both the Soviet Jew in me and with the distrustful post-Soviet in me.” Inspired by the contradictions that constitute his own identity, The Wayland Rudd Collection finds Fiks turning his attention outward, entangling his Jewish subjectivity with histories of anti-blackness. The result advances his ongoing project of accounting for the diversity of registers of memory and experience within and about the Soviet Union.

FROM ITS FOUNDING IN 1917, the Soviet Union’s project of revolutionary internationalism aimed to undo what economist Oliver Cromwell Cox has described as the proletarianization of race, in which racialization is enforced and materialized through labor extraction and the withholding of resources from the dominated nonwhite peoples who comprise the global majority. During the Cold War, which was also the age of mass decolonization, this project took on its most pronounced expression. As The Wayland Rudd Collection chronicles, the Soviet Union began reaching out to developing countries after World War II, its relationship with the African continent deepening with the advent of successful national independence movements, beginning with Ghana in 1957. Soviet leaders hoped their assistance would help persuade the leaders of emerging African states that they shared a common struggle against global capitalism, and that these newly independent countries would ally themselves with the USSR against the Euroamerican interests likewise seeking to expand their sphere of influence into decolonized Africa. These ties deepened as many young African nationalists and intellectuals, drawn to Soviet Communism, went to study in the Soviet Union. The Peoples’ Friendship University in Moscow, later renamed after the Congolese independence leader Patrice Lumumba following his assassination, was established in February 1960 with the explicit intention of educating poor students from Asia, Africa, and Latin America; it became an important intellectual and cultural hub for African and Afro-diasporic revolutionaries.

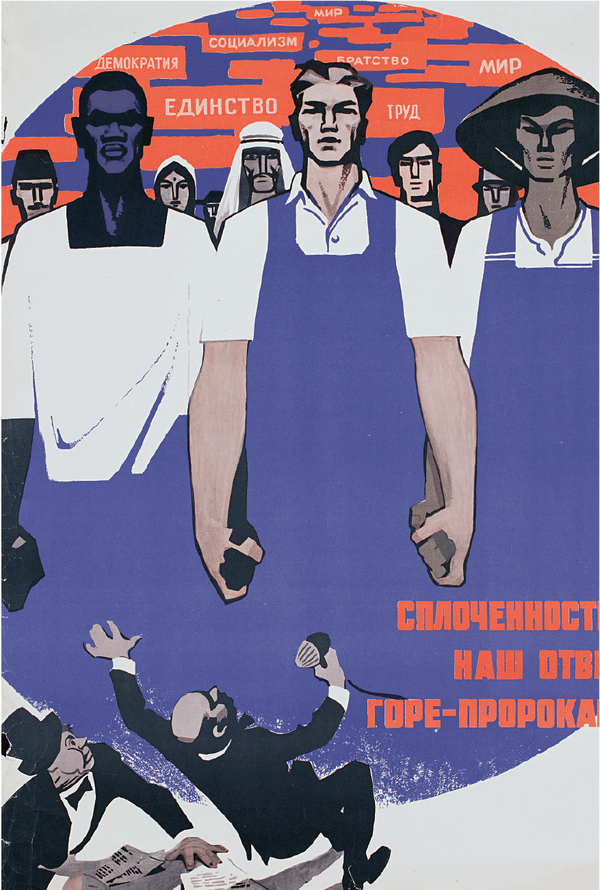

By exhibiting and analyzing images from Soviet archives, The Wayland Rudd Collection considers whether the USSR’s commitments to internationalist solidarity were genuine or rather an opportunistic means of undermining US hegemony. Fiks notes that in works of socialist realism, heavily ethnicized figures—stand-ins for the 14 non-Russian Soviet republics as well as the international proletariat—were often visually subordinated to a Russian man, an arrangement that evokes “a paternalistic relationship of tutelage” rather than the egalitarian ideals of communism. For instance, in a classic 1958 propaganda poster designed by Oleg Savostuk and Boris Uspensky, a blonde white man stands in the center holding a red flag that reads, “Raise the banner of proletarian internationalism!” while a brown-skinned Asian man and much darker Black man stand behind him. A nearly identical image appears on a 1969 poster by Vladimir Sachkov, and even in P.I. Vyuev’s more globally representative 1962 May Day postcard, a fair-haired white-skinned man still stands in the center. While these images advocated for the global Black cause, they nevertheless figured Black people primarily as empty vessels to be filled with political ideas. Poet Douglas Kearney’s “Hanged Posts or Rubbed Ruddy” reflects on this strategic instrumentalization of images of Black people in which support is paired with a denial of agency. “Do it feels this good being used?” he asks. “To be used thus is to be both propped up and prop. A prop that props while being propped is an object not meant to object.”

In works of socialist realism, heavily ethnicized figures—stand-ins for the 14 non-Russian Soviet republics as well as the international proletariat—were often visually subordinated to a Russian man, an arrangement that evokes “a paternalistic relationship of tutelage” rather than the egalitarian ideals of communism.

In addition to this literal sidelining of Black figures, Soviet imagery often represented Black people with stereotypically caricatured features. In her essay “Inventing an Aesthetics of Anti-Racism,” Christina Kiaer, a specialist in Soviet and Russian art, notes that early Soviet ethnographers’ “visual formulations demonstrated their ignorance of how to depict other races beyond colonialist stereotypes.” This same ignorance is on display in the work of later cartoonists. Anti-communist African leaders—such as Congolese President Mobutu Sese Seko, who deposed Lumumba in a US- and Belgium-backed coup—were often depicted naked, with ape-like features and motifs of “tribal” culture. A 1961 cartoon by the three-person collective Kukryniksy shows a saluting, simian Black man, naked except for gloves, a hat, epaulettes, and a belt of human skulls, mocking the traitorous Mobutu as a political puppet. (Given that Mobutu’s despotic regime was later marked by a campaign of “Authenticité,” an aesthetic and sartorial rejection of colonial influences, the cartoon also retrospectively reads as a racist joke about the “authentic” costume of the politically uncivilized—i.e., anti-communist—African indigene.)

Poster by Oleg Savostuk, 1958. The text reads: “Raise the banner of proletarian internationalism!”

Poster by Vladimir Sachkov, 1969. Foreground text: “Cohesion of our ranks is our answer to false prophets!” Background text: “Unity, Labor, Peace, Socialism, Democracy, Brotherhood.”

Poster by Kukryniksy, 1960. The text reads: “The Peoples of Africa will overpower colonizers!”

The most rousing and recognizable images in The Wayland Rudd Collection are of Black revolutionaries breaking their shackles—for example, Kukryniksy’s 1960 illustration of an African man using the length of the links to strangle a pith helmeted white colonizer holding a whip—which evoke Marx and Engels’s famous pronouncement that the proletariat has nothing to lose but their chains. The symbolic power in this particular representation lies in what historian Amanda Brickell Bellows, in her book American Slavery and Russian Serfdom in the Post-Emancipation Imagination, describes as the shared historical and political imaginaries around the abolition of chattel slavery in the United States and of serfdom in Russia. These images cohered a potent visual language that would later be deployed in gestures of solidarity from the Soviet Union to Black Americans and the decolonizing African continent.

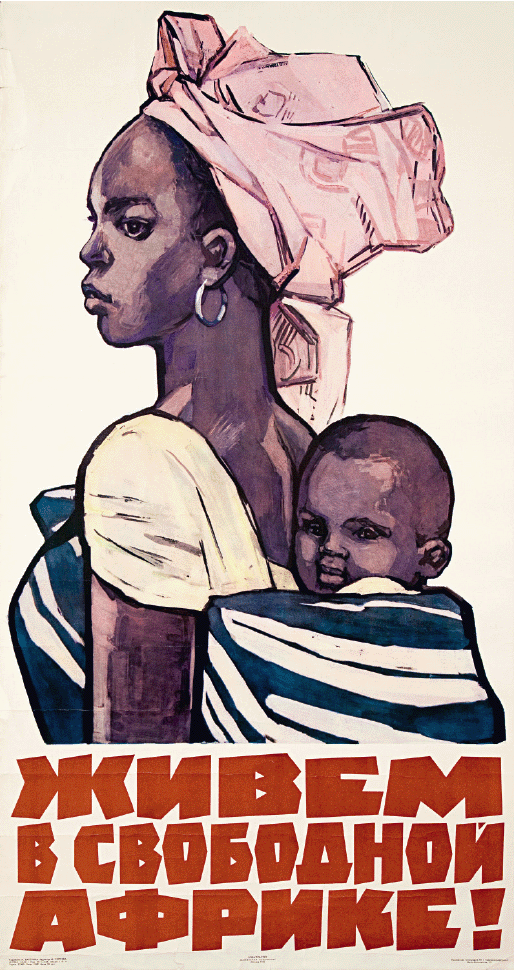

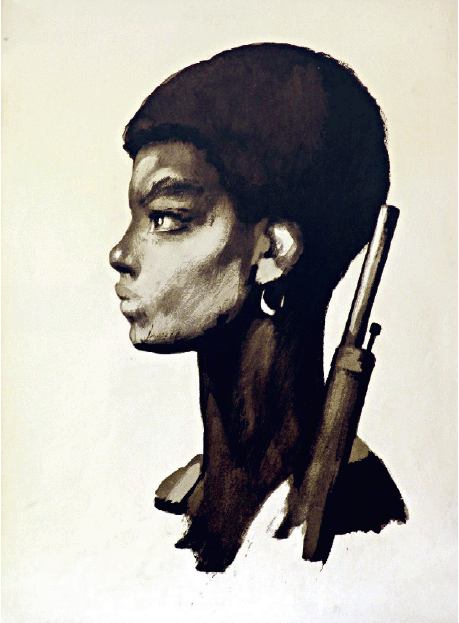

It’s no surprise, given the long-standing erasure of African women from the history of nationalist movements, that the representations available in this archive are overwhelmingly masculine. When portrayed at all, women almost always appear as mothers, as in Nina Vatolina’s 1965 poster of a beautiful, resolute woman with a baby on her back, accompanied by the text “We live in a free Africa!” In these images, African women are shown as proud supporters of freedom movements, rather than active participants in armed struggle. There are some notable exceptions: A striking postcard by Boris Prorokov captioned “Into the Struggle!” shows a steely-gazed woman alongside the barrel of her gun. But while leaders like Lumumba, Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah, Mozambican national liberation leader-cum-President Samora Machel, and freedom fighter Nelson Mandela appear frequently on stamps and posters, famous Black activists like Winnie Mandela and Angela Davis are nowhere to be seen.

Poster by Nina Vatolina, 1965. The text reads: “We live in a free Africa!”

Postcard titled “Into the Struggle!” by Boris Prorokov, ca. 1950s.

When portrayed at all, women almost always appear as mothers, as in Nina Vatolina’s 1965 painting of a beautiful, resolute woman with a baby on her back, accompanied by the text “We live in a free Africa!”

WHATEVER THE AMBIVALENCES of the Soviet Union’s relationship to the Black revolutionary imagination, the two were deeply connected not only in their aspirations but also in their defeats. Most of the infant states of decolonized Africa didn’t even end up with modest social democracies. Young revolutionary leaders were assassinated, and new countries got stuck with—and in many cases, enthusiastically embraced—neoliberalism. In Zimbabwe, for instance, just over a decade after gaining independence and less than a year before the Soviet Union’s dissolution in 1991, the government adopted a catastrophic Economic Structural Adjustment Program, which attempted to stimulate economic growth through neoliberal reforms such as privatizing social welfare and other public services. (Unsurprisingly, austerity spending and debt accumulation proved ruinous, eventually leading to hyperinflation and economic collapse.)

Considering the inescapability of the existential and material violence of anti-blackness in the West, it’s understandable that African and Afro-diasporan people would have found—or at least imagined—a safe haven in the Soviet Union. In his foreword to The Wayland Rudd Collection, philosopher Lewis Gordon describes how White Night’s “strange message of fleeing back to the United States offers Black audiences no solace,” because “what, then, is the conclusion but that socialism offers no more freedom for Black people than any other system so long as there is white domination?” The film depicted the ideological allure of the United States as so undeniable that, despite the “infrastructural guarantees” of Soviet socialism, it was preferable to be racially denigrated under the auspices of capitalist freedom at home. This was only punctuated by the Soviet Union’s collapse and the United States’ victorious emergence as the then sole global superpower. But even in the drastically altered political landscape of the present, the potencies of Soviet-era historical solidarities endure alongside the liberatory visions that decolonization sought to achieve. At the United Nations’ 75th General Assembly meeting, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa expressed solidarity with Palestinian and Western Saharan self-determination even while, back at home, he was enacting neoliberal austerity within his own country—a glimpse of the political resonances that powerfully endure even as they have been abandoned in practice.

Even in the drastically altered political landscape of the present, the potencies of Soviet-era historical solidarities endure alongside the liberatory visions that decolonization sought to achieve.

This fortifying political nostalgia that still defines geopolitical relationships in the present recalls what British historian Terence Ranger named “patriotic history”: the unassailable nationalist historiography that narrates continuations of a state’s revolutionary tradition, as well as its transnational solidarities. While it’s precisely this tradition that Fiks’s “critical nostalgia” means to complicate, for me, some of the most striking images in The Wayland Rudd Collection are the ones portraying decisive victory. In two posters by Eduard Artsrunyan, deep Black figures stand powerfully in the foreground bearing tools, as an orange sun (or the shape of the African continent) illuminate their figures—and their political horizons. In one, the Russian text reads, “Africa is building, Africa will win!”; the other declares, “Colonialism is doomed!” This anthology operates in the space between romantic mythologies and contemporary political realities, demonstrating the archive’s power to tell us not just what was lived, but what was hoped for.

Zoé Samudzi is a sociologist, art writer, and contributing writer for Jewish Currents.