This Is Not a Secret Jewish History of Stan Lee

The comics creator barely thought of himself as a Jew. What does it mean when fans and critics claim him as one?

IN HIS RECENT BOOK Stan Lee: A Life in Comics, the conservative columnist Liel Leibovitz proposes a skeleton key for understanding the life and work of Stan Lee, the legendary Marvel Comics creator, who died in 2018. In Leibovitz’s telling, the superheroes of the Marvel pantheon that emerged in the early 1960s must be read “as characters formed by the anxieties of first-generation American Jews who had fought in World War II, witnessed the Holocaust, and reflected—consciously or otherwise—on the moral obligations and complications of life after Auschwitz.” At length, he compares Spider-Man to Cain, the Thing to a golem, Mr. Fantastic to a dybbuk; he even goes so far as to argue that the Incredible Hulk and his alter ego are akin to the two versions of the biblical Adam theorized by the rabbinic scholar Joseph Soloveitchik. Leibovitz is not alone in his pursuit of Marvel’s Jewish undertones. In Lee’s twilight years and after his death, Jewish writers have repeatedly attempted to situate his work in the context of his Jewish background. In books and articles, speeches and seminars, Lee and the characters he is credited with creating are held up as icons of Yiddishkeit and extensions of the long Jewish textual tradition.

Given the existence of this mini-genre of Marvel exegesis, one might expect it would be possible to excavate a textured portrait of Lee’s Jewish identity. I know I did: When I began research for my book True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee, a biography out this month, one of my primary concerns was investigating Lee’s relationship to Jewishness. My motivations were perhaps not so different from those of the aforementioned scribes: Like many of my people, I have a perhaps unhealthy fixation on any famous Jew’s Jewishness. And so—through genealogical research, an investigation of the cultural milieus in which Lee and his family lived, close readings of the rare comments he made about Jewishness, and a long and revealing set of conversations with his brother, Larry Lieber—I attempted to suss out the true story of Stan Lee the Jew. What I found instead was an artist who spent much of his life trying—with apparent success—to distance himself from Jewish practice, Jewish communal life, even from the designation “Jewish.”

Stan Lee, I’ve come to realize, is an exemplary subject of a genre of writing, common in contemporary Jewish letters, that we might call the Secret Jewish History. Secret Jewish Histories take on a wide array of mainstream cultural objects—Easy Rider or James Bond or the music of Dolly Parton—fixating on the roles that Jewish people or institutions had on their creation or popularization. Criticism in this vein posits that the presence of Jews in the creation of a non-explicitly Jewish event or work is a crucial vector for understanding it. There’s an element of rabbinic interpolation involved, not unlike the process of explaining that some heroic character in the Torah who seemed to act immorally—Jacob stealing his brother’s birthright, King David committing adultery with Bathsheba—was, in reality, secretly enacting the will of God. The approach suggests that, if a Jewish artist says they didn’t put Jewish themes and motifs into a work, they are merely lying to themself.

Such revelations of crypto-Judaism induce a thrill in no small part because they allow Jews to claim someone or something as distinctively ours. There is some truth to be found in this approach—who you are really does have an impact on what you do—but all too often it betrays a deep cultural chauvinism and parochialism. This is especially the case when it comes to Jews who, like Lee, almost or entirely walked away from Jewishness. And yet, for related reasons, Lee is irresistible Secret Jewish History fodder for many of his Jewish admirers. Millions of fans have found succor and meaning in the Marvel legendarium since the 1960s; Lee both helped to create the company’s American myths and lived out his own as an avatar of upward mobility and moral uprightness. But myths work precisely because you can read into them nearly anything you want. And who wouldn’t want Stan Lee on their team?

SOME CLAIMS ABOUT LEE’S JEWISHNESS are indisputable. Stanley Martin Lieber, as he was originally known, was born to Romanian Jewish immigrants in Manhattan in 1922. He was raised and bar mitzvahed in Jewish communities in uptown Manhattan and the Bronx; some of the Yiddishisms he presumably learned in childhood would later make their way into his comic book dialogue and narration. Crucially, too, he entered the comic book industry around 1940, when it was dominated by Jewish businessmen and creatives, including his most significant collaborator—the comics writer and artist Jack Kirby, né Jacob Kurtzberg—a fellow New York Jew, and one whose Jewish identification ran deep.

Yet over the course of my research, I found virtually no instances of Lee publicly invoking his Jewishness. Late in life he told an interviewer, “Jewish people—and I include myself—I think we think a certain way.” In private correspondence, he sometimes jokingly invoked bar mitzvahs or peace in the Middle East, and there’s an anecdote about him once yelling at a bird that was bothering him, “For the Gentiles, you sing!” But those examples are the exception to the rule. In his co-written 2002 memoir Excelsior!: The Amazing Life of Stan Lee, Lee fleetingly identifies his forebears as Jewish—but never himself. Describing his and his wife’s struggle to adopt a child in the 1950s, he wrote, “My parents were Jewish and Joan is Episcopalian, and in those days it was more difficult to adopt in a mixed marriage.” The problem, in his telling, wasn’t his Jewish identity—it was others’ perception that he had one at all.

Those aforementioned Jewish parents, unsurprisingly, are central to any understanding of Lee’s Jewish identity, or lack thereof. His parents, Jack (born Iancu Urn) Lieber and Celia Solomon, each escaped horrific antisemitism in Romania as young people. In New York City, neither was Orthodox in their practice, but they were openly and distinctively Jewish: Celia lit candles and prayed every Shabbat; Jack attended synagogue and became an ardent Zionist who often ranted about the struggles of the Jewish people. Jack was a difficult man: removed, judgmental, and possessed of a dourness that only grew more intense as he struggled to find work during the Great Depression. As Lee himself admits in Excelsior, much of his own career was built on an effort to distinguish himself from his unhappy, unsuccessful father. He became the opposite of Jack, at least in public: a cheerful, relentlessly optimistic raconteur who deracinated himself to the point where anyone could think of him as a beloved relative. After Lee had found steady work and some modicum of fame within the comics industry—and had adopted the distinctly non-Jewish pen name “Stan Lee”—Jack would chastise him for abandoning the community. “He’d send him letters all the time, drive him nuts,” Lee’s brother Larry recalled to me in an interview. “‘Be more Jewish,’ ‘Observe the holidays,’ that kind of thing.” The letters became more plentiful after Lee married a gentile and, a few years after Celia’s death, had their newborn daughter baptized. As Larry put it, the act of telling Jack that his grandchild was a Christian amounted to “cruelty.” By the time Jack died in 1968, there was little love lost between him and Lee, in large part thanks to these divisions over Jewish identity.

How should we read the comics Lee was credited on, in light of this ambivalent inheritance? (I say “credited on” rather than “wrote” because there is another complicating factor here: The Marvel stories to which Lee signed his name were in fact written collaboratively, and it seems likely that Lee’s underlings were in fact their primary writers.) It is reasonable to speculate, as the writer Michael Chabon did in his popular 2000 novel The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay, that mid-century Jewish comics artists poured their own anxieties about assimilation into superheroes who, paradigmatically, had to hide their identities to make it in a world hostile to their true natures.

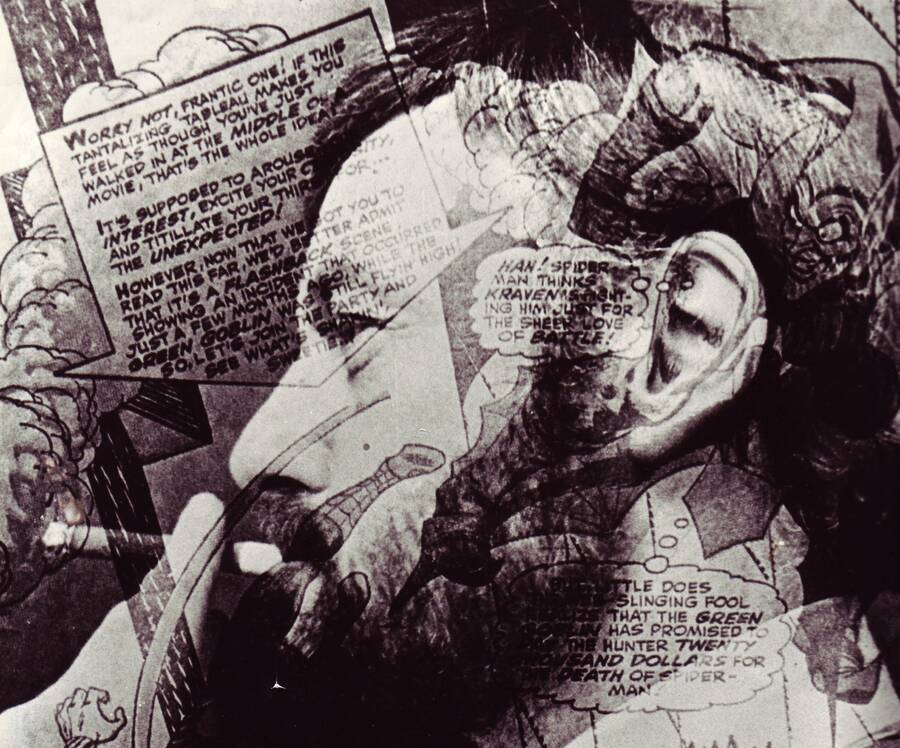

But some critics and fans have made wild leaps of logic, employing a sort of Talmudic exegesis of the comics attributed to Lee—a variation on the critical mode of philosopher Leo Strauss, long influential in conservative circles, in which great works harbor secret teachings, with exoteric meanings available to anyone and esoteric meanings available only to a chosen few. Spider-Man is an alienated neurotic who lives in Forest Hills, Queens, so these fans hold him up as a crypto-Jew—in fact, one recent Spider-Man movie features an alternate-universe version of Spidey who is implied to be Jewish. But there were a lot of alienated neurotics in 20th-century Queens, plenty of them non-Jews. It’s likewise true, as Leibovitz points out, that the intellectual Silver Surfer grapples with the godlike Galactus in a manner not wholly unlike Abraham arguing with the God of the Hebrew Bible. But attempting to negotiate with divinity is in no way a solely Jewish endeavor. The closest hit in this search for Lee-era Marvel’s Jewishness is the rocky-carapaced Thing, who spoke in a Lower East Side brogue and, many decades later, was canonically identified as Jewish. But in the days when Lee was working on the character’s stories, none of that was explicit, and any streetwise social reject could conceivably find themself in him. Yes, Lee’s Jewishness may have informed these tales; no, we should not fall into the trap of an overly literalist reading of these comics.

All of this suggests we should be careful about any attempt to map out the Secret Jewish History of Lee’s work—or, for that matter, anyone’s. I have already confessed that I understand the temptation to indulge in Jewish mythmaking. Indeed, when first mapping out this essay, I had planned to identify Lee’s distance from Jewish identity with the figure of the echad rasha, the Wicked Son of the Pesach seder, who frustrates his elders by remaining aloof from his heritage. But would that not have been just another attempt to embellish the Jewish bona fides of someone who didn’t want them? I maintain that Lee’s Jewish saga is crucial for understanding how he developed, but I have had to resist the temptation to read the influence of that Jewishness on his work as though I were among a chosen few who could decipher it. There were, to be sure, secrets of Lee’s Jewish history, but not, in fact, a Secret Jewish History.

To posthumously conscript Lee into a Jewishness he did not want is to play an intellectually dangerous and narcissistic parlor game. Let him dwell in the liminal spaces of Jewishness in death, as he did in life, joining all the other fascinating Jews of assimilation who have come before and since. Even if Lee was, in some ways, one of us, he does not really belong to us.

Abraham Josephine Riesman is the author of Ringmaster: Vince McMahon and the Unmaking of America and True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee. She is a freelance journalist and a board member of Jewish Currents.