The Gaps in Our Stories

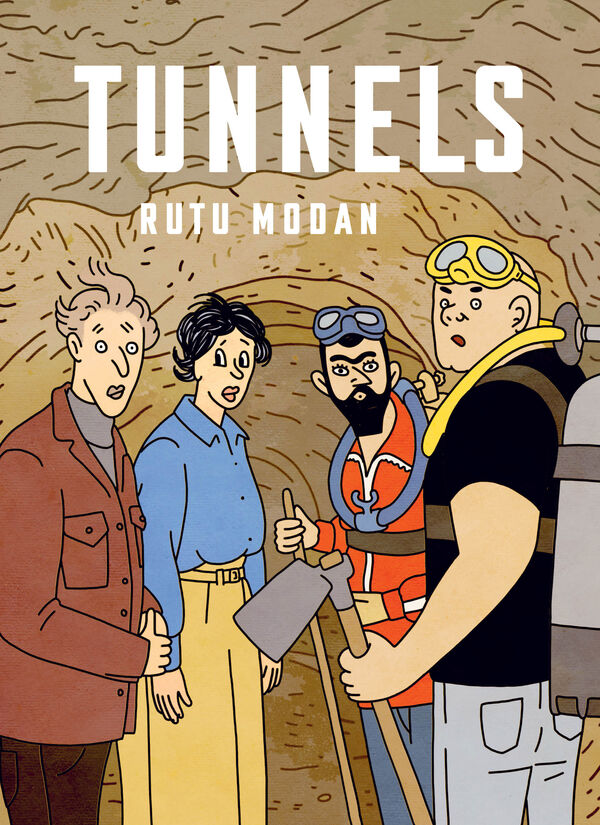

A conversation with Israeli cartoonist Rutu Modan on her new graphic novel, Tunnels.

Nature, as they say, abhors a vacuum, and the human mind abhors a gap in knowledge. The historical and archaeological record of Jewish civilization is filled with such gaps. But what would happen if one of the biggest gaps of them all could finally be filled? What would happen if someone found the Ark of the Covenant?

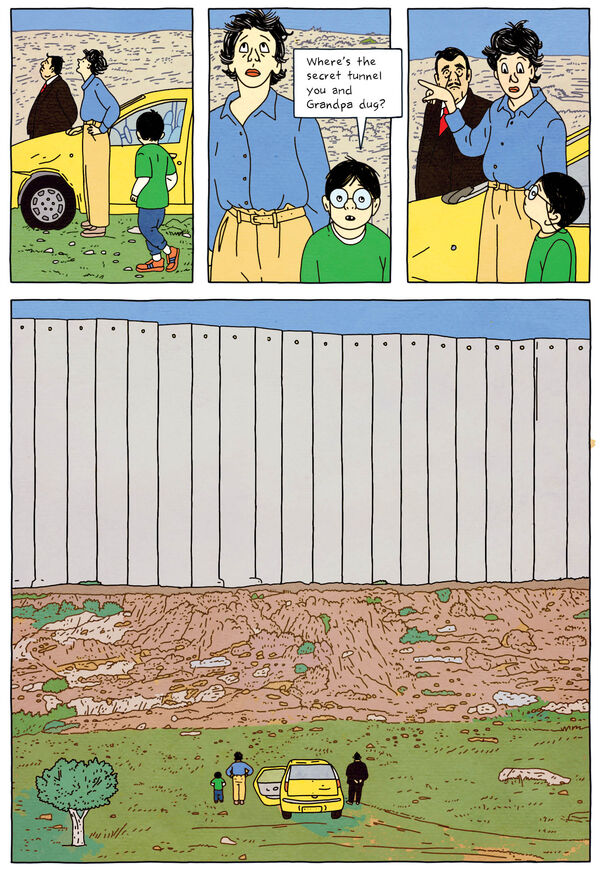

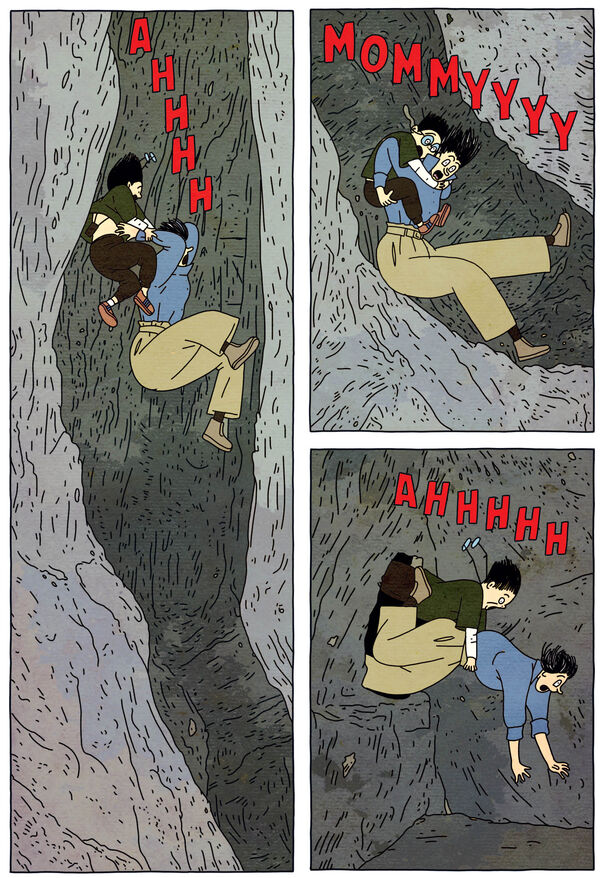

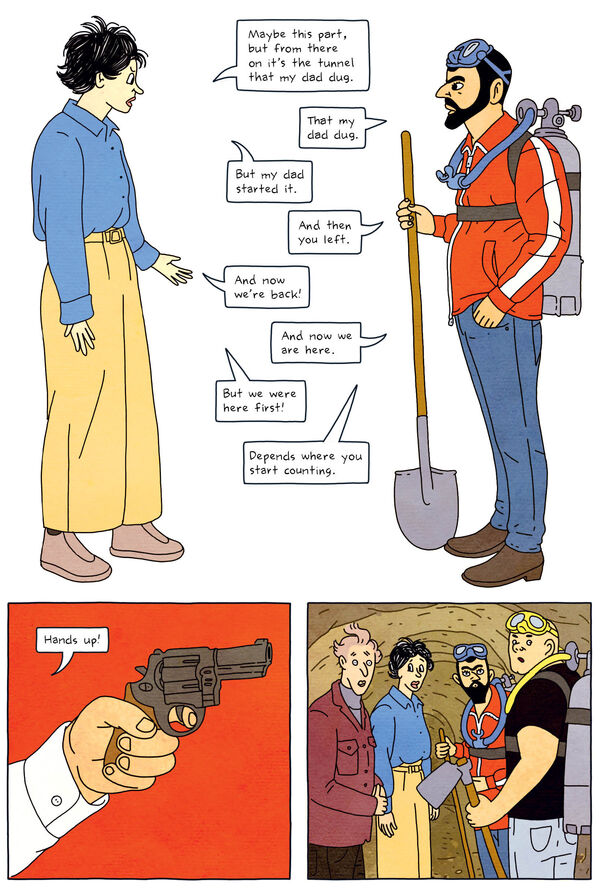

That’s the question explored in Israeli cartoonist Rutu Modan’s new graphic novel, Tunnels. The Bible tells us that the Ark contained the tablets brought down from Sinai by Moses after the revelation of the Decalogue. Infinitely more sacred than the Herod-built Western Wall—and allegedly able to make its possessors invincible on the battlefield—it has been sought for millennia. In Modan’s heavily researched story, the daughter of a renowned Israeli Jewish archaeologist attempts to excavate the Ark, only to discover that it’s on the other side of the Separation Wall, in the West Bank. The woman enlists an unlikely group of allies from across the social spectrum in Israel/Palestine, and adventure ensues.

I caught up with Modan to discuss the topic of gaps and the delight and danger of filling them. Our conversation has been condensed and edited. It originally appeared yesterday in the Jewish Currents email newsletter, to which you can subscribe here.

Abraham Riesman: What were some of the major gaps in your knowledge that this book helped you to fill?

Rutu Modan: When I write comics, I always have a question in mind that I want to answer for myself. If I know everything, then it’s not an adventure.

I had the idea to write a book about this woman who is going to dig illegally for the Ark of the Covenant. I knew a guy who used to do that with his father between the ages of 14 and 17. They actually dug a tunnel, looking for the Ark, back in the 1980s. Years later, we became friends as students, and he told me about it. At the time I just thought it was funny. By then it had been about four or five years since they stopped, because the First Intifada was happening and they had been digging in the West Bank, near Jerusalem. I forgot all about it.

I finished The Property [ed. note: Modan’s first graphic novel, published in 2013, about a Jewish family traveling to Warsaw to reclaim property they were forced to give up during the Holocaust] and I was looking for a story. I was talking to another friend, an interactive designer who worked on the Israel Antiquities Authority, and I remembered this story. I asked myself, Why did they do it? I knew the family, and they were not more crazy than any other family. They were not really mystical people. So why did they do such a crazy thing? To me, it sounded like a treasure hunt. So I said, Okay, this can be a story.

I went to talk with the older friend and I learned about archaeology, and then questions started to arise. Why would regular, non-religious people do this? Zionism was supposed to throw away all these mystical things! But the roots of Zionism are in the Bible, in these old stories! That’s what the connection is between Jews today: It’s not genes, it’s stories. Zionism took those stories and used them practically: Based on the story, you do things in the world. So the mystical thinking is still there and it influenced everything here.

But it’s not just a treasure hunt; there’s something to explore behind it. I studied in the secular part of the Israeli education system, but still, every week for years, I studied the Bible in school. In first grade, I studied it as a legend from the past, as a set of stories that were our culture. And then, around fifth grade, it started being taught like history. The message was, “It really happened.” It starts around Exodus, and then especially when the Jews enter Israel and conquer the land. It’s the same as the story of Zionism. But they don’t tell you it’s history. If you asked the teacher, she wouldn’t lie to you and say it’s history.

So one of the first things I did to prepare for Tunnels was to study, for the first time in my life, the actual ancient history, and figure out what we know is true and what are just stories. Nobody really knows. It’s all based on archaeology and what you are able to find. Maybe there are things you never find. Maybe there are things that were never there. So I took an Open University course about this exact question. The lecturer was a very famous archaeologist, Israel Finkelstein. He reads the Bible, looks at what has been found, and tries to understand what really happened.

I also spoke with archaeologists and collectors. I started to see how archaeology is connected with crime and money and history and politics. I’m ashamed to say—it’s not that I didn’t know it, but I didn’t think about it before.

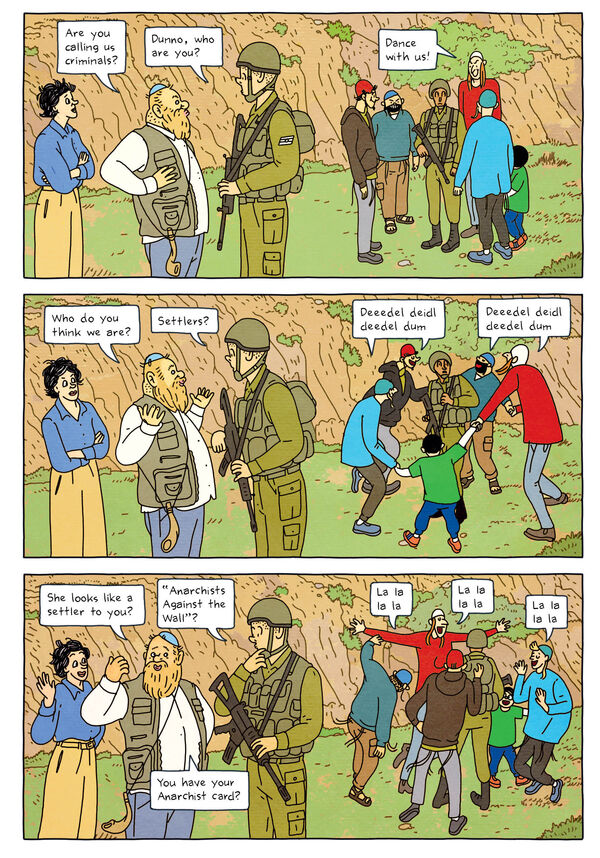

The ancient kingdom of Israel was actually in the West Bank; it wasn’t here in Tel Aviv. What I realized is that in Israel, if we have any right based on ancient history, it’s in the West Bank. This was shocking and tragic to think about, because the settlers really believe this story and it’s important to them. They would never give it up.

I went to the West Bank a few times to speak to people. In the progressive lefty circles I belong to, you avoid the West Bank. There’s even a phrase: “I’ll go there with a passport.” But I had to give this up, because if I wanted to do this book, I felt that I had to see it with my own eyes. I hadn’t been there in more than 20 years. Now I think it’s good to go; not going is not knowing. I learned a lot. It’s so near!

AR: If you’re trying to see Area A, the Palestinian population centers, the government won’t even let you in. They’ve got those big red signs at the entrances.

RM: I can’t go. I went once with a guy, a fearless journalist I know who has many friends in the West Bank. There were all these gaps to fill, and it wasn’t only politics. I am an atheist, but I didn’t want to write religious settler characters who are stupid. Maybe, deep down in my mind, I think I am right and they are wrong, but I cannot write like that. To write them, I have to put all these stereotypes aside. So I spoke with religious people I know who are intelligent and whom I adore. I tried to understand how they think.

I took a year to do research, and I learned so much. There were so many things I had to put into the text, including the stories from the Bible that I mentioned. And I found that the Palestinians have their stories, too. I had a similar experience when I did The Property—like, the Poles have a very different story than I have. So I already knew that you can’t change the story of others.

I was more or less convinced that the events of the Book of Exodus didn’t really happen, at least not the way they’re described. I don’t think there’s a serious archaeologist who will say otherwise. At first, that was a little bit shocking, but then I realized that it just doesn’t matter for me. The story is so important and embedded in my identity that the fact that it’s just a story doesn’t change it. The idea of Exodus is really what matters.

Of course, it’s more complicated than that. I’m not saying that the only important thing is what you believe in, if it really didn’t happen. But I think it’s interesting, especially for me as a storyteller, to think about how stories shape us and how old stories from thousands of years ago affect our daily life.

AR: And how we tell stories to fill in the gaps where we don’t have something more concrete than a story. I’ve been reading Chaim Potok’s Wanderings, which is a history of the Jews; it’s not very historically accurate, but he has these parts where he talks about gaps in the historical or archaeological record, and he’ll have little teases of his ideas about what might have happened. It’s thrilling. But, of course, filling in a gap with a story can be dangerous if you lose sight of the fact that it’s fiction.

RM: I have another example, based on the title of that book, “wandering.” After the Roman exile, the burning of the Second Temple, and another rebellion, you have almost 2,000 years of wandering Jews. But when I was studying for the book, I realized that the idea of the wandering Jew is much, much older. Abraham was a wanderer. He came to Israel and he was told not to mix with other nations and to be a stranger. You are not part of the place, and yet you are part of the place. It’s the same story with Jacob in Egypt, and then there’s the exile in Babylon, which is actual history.

Then there’s Zionism and this idea of Jews as people who don’t want to belong, who come to a place that is both theirs and not theirs, and stubbornly stay outsiders. Who are the settlers, if not people living in a place that is theirs and not theirs, and who try to ignore that they live around people who don’t want them there? What is the impact of us sticking to these stories?

AR: The elephant in the room here is Steven Spielberg’s first Indiana Jones movie, Raiders of the Lost Ark, which, of course, features the most famous hunt for the Ark.

RM: I love this movie. I’ve seen it a million times.

AR: Spoiler alert for readers of this interview, but the two-page spread that ends the book—the last “shot,” if you will—feels like a deliberate riff on Raiders. The Ark has been found, but it ends up in the possession of people who don’t value it much and put it in a semi-anonymous pile alongside other miscellaneous junk. However, in Raiders, the unappreciative owners are the US government, while here, they’re the Islamic State. That was a deliberate echo, right?

RM: It’s one of the most perfect endings in cinema. It’s so ironic and so wonderful. It also has this double meaning. One interpretation is that the Ark isn’t important—you put it there, and nobody notices it, and it’s lost again forever. But, on the other hand, Spielberg is an American patriot, and he leaves the Ark in the hands of the Americans. Maybe it protects them and makes them the strongest nation on Earth.

I wanted to find an ending to compare with this. But I couldn’t come up with anything strong enough.

AR: But it works! With Raiders, Spielberg is an American Jew trying to talk about the ambiguity of Jewish civilization’s Middle Eastern origins and who that history belongs to. But he’s an outsider and it’s not a very subtle take. Your book, on the other hand, was written by a Jew in the Middle East who has no patriotic attachment to America. So you end up with this ending where you’re pointing out that the US and ISIS have more in common than they’d like to think, when it comes to what they’ve done to the region, its people, its treasures, and its history. The whole book is about taking the thought experiment of finding the Ark and asking how it would actually play into the politics and divisions of the place. Do you think we’ll ever find it?

RM: No, no, although there’s no reason to think it didn’t exist. It was common to have a movable Temple to take to battlefields. The Ark was made of wood and covered with gold, but probably the gold was taken away and used. Some scholars think it was destroyed because it was a statue that you worship, an object, and when true monotheism took over, there was a king who destroyed all the sacred objects because God was supposed to be abstract. So maybe he destroyed it. But nobody knows. This is why I could imagine whatever I wanted.

AR: Exactly!

RM: I tried to imagine it according to my

values. One of the questions was what it would look like. There are

descriptions, but now, the image is these two angels with wings covering

it. In the text, it’s written that these are cherubs facing each other.

I learned that “cherubs” are what are usually described in the ancient

world as figures that are half-man, half-animal. It’s an Akkadian word.

But to draw these figures on the Ark would be too much of a statement;

it would say that the Ark was pagan. I didn’t want to take this point of

view, because nobody really knows. So I said, okay, it broke and

disappeared through the years.

But I kept the measurements. I’m very rigid, so I used exactly the measurements in the Bible and drew it according to that size. I needed it, in my head, to be real.

Abraham Josephine Riesman is the author of Ringmaster: Vince McMahon and the Unmaking of America and True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee. She is a freelance journalist and a board member of Jewish Currents.