MIDWAY THROUGH Avrohom Eliyohu Plotkin’s Yiddish short story “Kaddish Denied, or The Live Orphan,” a proletarian carpenter named Moshe “burst[s] out in protest,” upsetting what should have been a tranquil Shabbos table scene. Sitting with him are his wife and nephew—Sholem’ke, who has come to live with the childless couple after the “disappearance” of his father by agents of the Soviet state—but he doesn’t address them. Instead he argues “with the world itself, at-himself-with-himself.”

Moshe is immiserated by his double life, praying and celebrating Shabbos in private while publicly acquiescing to the erasure of religion from Soviet society. “Is this called living?” he demands. “This is forbidden, that is forbidden, going to shul induces fear, davening at home induces fear, the shoychet [kosher butcher] is afraid, the melamed [Torah teacher] is afraid . . . How can a person live in a world like this one?”

Moshe’s eruption comes in the wake of another speech on the subject of religious life, this one delivered by Berele, a member of the craftsmen’s cooperative to which Moshe also belongs. Moshe repeats his colleague’s proposal that the group celebrate the upcoming Pesach holiday “as a collective,” foregoing a traditional seder:

There’ll be a concert, with music and dance, and there we will be given a proper, enlightened understanding as to the true significance of Pesach in Jewish life, and likewise that all the laws of Pesach—eating matzah, maror, and the like—are all a product, a legacy, of the bourgeois religious world . . . They, they, the bourgeois and the religious, have tricked us and brainwashed us in order to advance their own ends.

Moshe is incensed by Berele’s characterization of the laws of Pesach as relics of bourgeois trickery. For Moshe, Torah is the ultimate source of all social and spiritual aspirations, and the practice of its precepts is a challenging and critical pursuit. The idea that the Torah might have “coddled and fallen in line with the bourgeois,” or that the bourgeois might have “supported and upheld” the Torah’s demanding ideals, strikes him as a bitter joke, and the politicized secularization of Pesach that Berele proposes seems a tragic emblem of the materialist reductionism being imposed all around him:

You understand? They’ve brought everything to an end, they’re finished with the rov [communal rabbi], with the shoychet, with the mikveh [ritual bath], with kosher meat . . . so smoothly does he make this shidduch [marriage]—coupling up these two—“the bourgeois and the religious.”

First published in a 2014 volume of Plotkin’s correspondence, articles, poetry, and stories, “Kaddish Denied” was probably penned in the short period between his escape from the Soviet Union in 1946 and his untimely death in 1949. It’s a semi-autobiographical tale: Plotkin was a rabbi in Ostashkov, a provincial town halfway between Moscow and Leningrad, from 1923 until 1928, when he went into hiding. In October of that year, Anatoly Lunacharskii—the Soviet commissar of education—delivered a speech in Leningrad declaring war on religious activists like Plotkin, whom he dubbed “Schneersohnovschina.” This term referenced their association with Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn (also known as “Rayatz”), the sixth rebbe of the Hasidic dynasty of Chabad-Lubavitch, who had been arrested and sentenced to death a year earlier. (An international pressure campaign secured a commutation and safe passage to Latvia.)

Unfolding in the aftermath of Rayatz’s arrest and departure, “Kaddish Denied” is an intimate dramatization of underground identity formation. One of its most sharply defined characters is Moshe the carpenter, who experiences the reductive “shidduch” between people of faith and the bourgeois as a glib farce and a disenfranchisement of the soul. Yet in the eyes of the Evsektsiia (the “Jewish Sections” of the Communist Party), a frum worker was regarded as an “enemy of the workers,” a charge given formal weight in Article 58 of the Russian Penal Code, which made anything that could be construed as “counter-revolutionary action” punishable by death.

A century separates us from the first decrees targeting religion in the aftermath of the Bolshevik revolution, yet the false dichotomy between commitment to progress and commitment to faith remains implicit in much ideological discourse and debate.

A century separates us from the first decrees targeting religion in the aftermath of the Bolshevik revolution, and decades have passed since the Soviet Union’s collapse. Yet the false dichotomy between commitment to progress and commitment to faith remains implicit in much ideological discourse and debate. Karl Marx’s caricature of religion as “the opium of the people” has cast a long shadow. A sociological study of 21 Western European countries from 1990 to 2008 published in the Journal of Contemporary Religion found that “on average, people with socialist political views are more inclined to hold negative views about religion than people with other political views.” Though there are important exceptions—especially in the Global South, which was notably excluded from this study and where Catholic liberation theology has long flourished—socialism has been generally understood as a secularizing force. Indeed, this magazine, which was founded in the orbit of the American Communist Party, is still published by the Association for Promotion of Jewish Secularism.

Soviet Yiddish propaganda poster titled “Religion is the Enemy of Workers of All Nationalities,” ca. 1929–1931.

Likewise, contemporary Chabadniks are likely to associate socialism with their inherited memories of Soviet persecution. Thousands can recount stories of grandparents and great-grandparents who were shot or sent to the Gulags for practicing and perpetuating their Jewish way of life. Those who evaded arrest lived in fear, in hiding or on the run. Their refusal to work on Shabbos usually meant that they couldn’t find official employment; often, they survived by laboring in home workshops and selling goods on the black market. The stories of this struggle, experienced not only by rabbis and kosher butchers, but also by laborers, homemakers, and artisans—ordinary men, women, and children—are the threads from which the collective story of the Chabad community is woven. Take, for example, the story of Sarah Katsenelenbogen (known among Chabadniks as “Mumme Sarah”). Her husband was disappeared in 1937, and she was left alone with five young children. She insisted on raising them as religious Jews, refusing to send them to government schools. After World War II, she helped mastermind the mass escape of Chabadniks (including Plotkin and his surviving family members) into Poland. She never made it across the border herself, and she died in 1952 while incarcerated by the Ministry of State Security, which conducted surveillance and repressed political dissent. Today, more than a hundred of her direct descendants serve in Chabad institutions all over the world.

Given this background, it is understandable that contemporary Chabadniks often respond to any invocation of socialism with suspicion, or even fear. This reflex is part of a broader matrix of factors that skews political inclinations among Hasidic Jews to the right, so that when it comes to the ballot they tend to be more aligned with political elites than with working people whose interests might appear much closer to their own. Last year’s Pew study of American Jews showed that those who identify as Orthodox tend to have lower household incomes than those affiliated with other denominations, suggesting that contrary to the pervasive stereotypes, many are workers, modern incarnations of Moshe the carpenter.

As a member of the Chabad community myself, as well as an academic who studies the movement’s intellectual, social, and literary history, one of the reasons “Kaddish Denied” grabbed my attention is the way it centers a character whose very identity is a rejection of the false bifurcation between working people and religious Jews. Plotkin’s story, it seems, might help us cast off this antiquated binary.

CHABAD EMERGED AS A DISTINCT STREAM within the wider Hasidic movement at the end of the 18th century, under the leadership of Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi. His classical work of Hasidic thought, Tanya (1796), demystified Kabbalah and made contemplative mystical practices accessible, empowering readers to overcome spiritual and material anxieties through the joyful alignment of thought, speech, and action with divine wisdom and will. Over the course of the 19th century, Chabad (centered from 1813 in the village of Lubavitch) became the dominant Hasidic group in the region that now encompasses Belarus and stretches south into the eastern parts of Ukraine, north into Latvia, and east into Russia. Chabad’s heady mix of cerebrality and spirit, combined with a rich tradition of literary and melodic production, was seminal to the development of Eastern European Jewish culture. Modernist figures like the artist Marc Chagall and the playwright and folklorist S. Ansky—famed for his play The Dybbuk—both emerged from the Chabad milieu.

In the first decades of the 20th century, Chabad-Lubavitch was led by Rabbi Shneur Zalman’s great-great-grandson, Rabbi Shalom DovBer Schneersohn (“Rashab”). Advocating for the primacy of traditional Torah authority in institutional Jewish life, he successfully competed with the Jewish aristocracy, who sought the acculturation and reform of Russian Jewry, and who had previously dominated representation of the Jewish community to the tsarist government. Rashab celebrated the tsar’s 1917 abdication, comparing it to the fall of Pharaoh, and in subsequent elections for a new All-Russian Jewish Congress, he mobilized a united religious front that captured a significant share of the vote. By then, however, October’s Bolshevik Revolution had ended Russia’s brief moment of emancipation and initiated a bloody civil war.

When Rashab died in the spring of 1920, the networks and institutions he had built had been all but decimated. In the wake of war, pogroms, famine, and disease, the Evsektsiia—aided by other agents of the new state—were beginning to systematically stifle traditional Jewish life. But the students of Rashab’s rabbinical school had internalized his vision, and his son, the aforementioned Rayatz, rallied them to resist the Evsektsiia’s campaign of compulsory secularization.

“Kaddish Denied” is set in the 1930s and ’40s, the darkest and most difficult period for Chabadniks who remained behind the Iron Curtain. Sholem’ke grows up in the shadow of his most vivid childhood memory—the night that uniformed men ransacked the dank apartment he shared with his parents (“halfway underground, halfway a grave”) and took his father away:

My small childish mind—I was seven years old at the time—doesn’t grasp what is happening: Who are they looking for? . . . and then they find a card, “the Rebbe’s portrait.” One of them, apparently a Jew, shows it to the others:

“Do you see? Schneersohn!”

They ordered Father to dress and to come with them. Father came over to my small bed, bent over, and kissed me; a powerful and final kiss. A few large tears—warm, hot, boiling like blood—tumbled from his deep black eyes onto my forehead. Then he gave my mother a fiery glance, his eyes now bloodshot. He kissed the mezuzah, opened the door and was swallowed up in the unending darkness of the night.

Sholem’ke remembers his father as an unhappy kaloshnik, a mender of old galoshes and rubber boots. But as he pieces together the “mish-mash of impressions and incomplete images” that survive this shattering event, he comes to understand that his father was actually a rabbi “forced to abandon his position” due to “the more recent circumstances.” The arrest and presumed murder of Sholem’ke’s father draws on real events with which Plotkin was intimately familiar. On a single night in 1938, 12 of his closest friends and colleagues were arrested, tortured, and later shot. The location of their communal grave, in the Levashovo Wasteland near Leningrad, remained unmarked until 2014.

Amid the horror of this repression, the light in the darkness was chassidus—Chabadniks’ term for their rebbes’ teachings. Reflecting on his own experience as a teenager and a young adult, Sholem’ke explains how the “rich and spirited conceptual forms” of chassidus endowed him and his friends with “a new life-meaning . . . a glorious inner world, fruitful and divine.” The new world that it conjured within gave them the ideological conviction to meet “all the difficult circumstances of life” with “courage, poise, and the capacity to endure.”

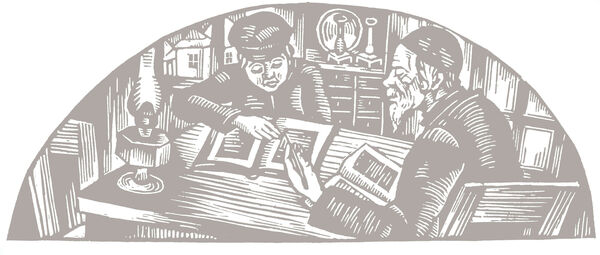

S. Yudovin: Melamed and a boy, 1921, woodcut

Crucially, the study of chassidus also enables Sholem’ke to attain a healing sense of togetherness with his father. He recounts a time, in the period before the arrest, when his father taught a chassidus class to a group of clandestine yeshiva students:

In that room about thirty young men had gathered . . . their eyes agile and darting, as if afraid, and their faces pale or yellowed, as if prematurely aged. Between them, however, there was a palpable spirit of friendship and brotherhood . . . They all sat down around the table; books appeared, and they began studying . . . My father studied with them. They asked. He answered. Soon an affectionate debate was underway; with heat, with intensity . . . Then, one by one, they took leave, slipping quietly and surreptitiously out the door.

For Sholem’ke, this experience was an initiation of sorts into the underground Hasidic brotherhood, and it leaves him with one of the few “complete and whole pictures” that he can return to and relive again. Plotkin’s tale shows us how countercultural ideology and camaraderie becomes the stuff of memory, of identity, of intergenerational continuity and community. During this period, historian David Fishman writes, Chabad activists “were infused with the passionate idealism and heroic spirit of Russian revolutionaries.” As the story comes to a close, Sholem’ke reflects on how he has now grown into one of those young men his father used to teach, a product of the clandestine yeshiva network, resisting the bounds of time itself. “The case is closed on me ever seeing my father,” he reflects, “but here I have found an internal bond, a soul bond . . . a balm for all my unhealed wounds.”

A similar sort of “soul bond” underpins the intergenerational development of Chabad into a global network in the post-Soviet era. The new Chabad centers in America, the United Kingdom, Australia, and France were all established by veterans of the battle for the preservation of Judaism in the USSR. The memory of their struggle against the Soviet regime has been built into the Chabad calendar—which designates annual commemorations of important historical moments—and into chassidus itself. The last teaching of Rayatz’s son-in-law and successor, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson (“the Rebbe”), studied anew each year by contemporary Chabadniks, explicitly casts the Soviet era struggle as a prefiguration of the contemporary fight against American secularization. In this 1992 treatise, the Rebbe argued that now that secularization was no longer enforced at gunpoint, but equably gifted by emancipation, Jewish identity could no longer be animated by confrontation with external antagonists, but must instead be constructed from within.

During this period of repression and underground study, historian David Fishman writes that Chabad activists “were infused with the passionate idealism and heroic spirit of Russian revolutionaries.”

This sense of cultural and ideological continuity is captured in a wry anecdote that circulates among Chabadniks today, originating with the Russian Israeli activist Betzalel Schiff and retold by the Chabad writer Tzvi Freeman. The story goes that following the Soviet Union’s collapse, a former KGB officer visited 770 Eastern Parkway, Chabad’s iconic Brooklyn headquarters. He was astonished to find that, even in America, his old adversaries still lived as they did in the old country, praying in a basement, sitting on hard wooden benches, and eating canned fish and vodka. Why did they live as if they were still underground? It was then that the former officer “realized that which I should always have known. You people are not just another religious sect . . . You are not bourgeois Americans! You are revolutionaries! You are partisans!”

FROM HIS OFFICE IN BROOKLYN, the Rebbe continued the struggle for religious freedom begun by his predecessors. He had left the USSR together with his father-in-law in 1927, and after spending the intervening years in Europe, he arrived in New York in 1941. His own father, Rabbi Levi Yitzchok Schneerson, remained in Ukraine, refusing to abandon the community whose rabbinate he headed. Under increasingly dire circumstances, he maintained a semblance of traditional Jewish life, teaching Torah and writing kabbalistic commentaries. In 1939, he was arrested and exiled to present-day Kazakhstan, where he died ill and emaciated in 1944. By that point, nearly 17 years had passed since he had last seen his son, and communication had been disrupted by World War II.

Beginning in the 1950s, the Rebbe’s operatives entered the USSR as visiting professionals, diplomats, or tourists to support a covert network that stretched from Leningrad to Samarkand. They smuggled in Jewish ritual articles and books that couldn’t otherwise be obtained in “yenner medinah” (“that country”), as well as clothing and other goods that could be resold on the black market to help provide for Jewish families. Detailed reports of these trips kept the Rebbe apprised of the circumstances of communities and individuals throughout the Soviet Union.

Critical of tactics championed by establishment organizations like the American Jewish Conference on Soviet Jewry, the Rebbe argued that public protests would antagonize Soviet officials and prove counterproductive. Instead, he advocated for a strategy of “quiet diplomacy” that depoliticized the plight of Soviet Jews and appealed to Soviet officials to live up to their own ideals by protecting and expanding rights to freedom of religion and freedom of movement. He didn’t want Jews to see themselves as bargaining chips in the international Cold War showdown, but as agents in their own right, bearers of Judaism’s own legacy and mission, which he believed transcended geopolitical distinctions.

One particularly memorable expression of the Rebbe’s approach came at the grand Lag B’omer parade held outside his Brooklyn headquarters in 1980. Looking out from a podium at the crowd of thousands on Eastern Parkway, the Rebbe suddenly began to speak in Russian to an audience thousands of miles away. Freedom of religion, he vehemently declared, was guaranteed by the Soviet Constitution, and the time had come for Soviet citizens and officials alike to recognize the rights of “the Jewish father or grandfather, mother or grandmother” to “teach their sons and daughters what the Torah says to do,” without disturbance. It was those who framed such activities as illegal, he charged, who were the real “propagandists” and “criminals.” Rather than vilifying the Soviet regime as inherently illegitimate and oppressive, the Rebbe highlighted the ideals that the regime itself had enshrined in law, and went so far as to argue that if only those laws would be properly upheld, “this will hasten the time when all of us . . . will go and greet the Moshiach with the complete redemption,” and “everyone will have true freedom in their everyday lives.” Within a few days, cassette recordings of the Rebbe’s 17-minute speech would be smuggled into the USSR, where transcripts were widely circulated as samizdat, or dissident literature.

The Rebbe’s speech is remarkable in its refusal to accept the reductive opposition between socialism and religion. Despite the decades of brutal and systematic oppression experienced by Soviet Jews collectively, by Chabadniks in particular, and by the Rebbe and his immediate family personally—and despite his central role in the ongoing struggle—the Rebbe did not condemn socialism as a whole. This attitude is also reflected in a Shabbos talk delivered in 1974, in which he rebuffed the claim that he was an anti-socialist and noted that as an abstract ideology, socialism encompasses “good elements” that derive from the Torah. He argued that existing socialist regimes had failed to put those ideals into practice.

In 1963, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson wrote, “I was never of the opinion that there must be a conflict between a Jewish-socialist worldview and a traditional religious ideology and lifestyle. In Russia, in the midst of the burning fervor of the Revolution, I personaly knew many socialists, including radicals, who were observant of Torah and mitzvahs to the fullest extent.”

One aspect of this failure stemmed from the very shidduch that had so vexed Moshe the carpenter. In a letter dating from 1963, the Rebbe wrote, “If there are still people who see a conflict [between socialism and Jewish observance] in terms of foundational ideals, this simply comes from ignorance.” He explained further in another letter written that very same day:

I was never of the opinion that there must be a conflict between a Jewish-socialist worldview and a traditional religious ideology and lifestyle. In Russia, in the midst of the burning fervor of the Revolution, I personally knew many socialists, including real radicals, who were observant of Torah and mitzvahs to the fullest extent, and were proud of it, and this did not hinder them from occupying leadership positions in the socialist movement there. Obviously, this was so only until the “true” [“emesser”] socialism arrived.

Notably, the Rebbe deliberately spelled the word for “true,” “emesser,” with Soviet Yiddish orthography, almost certainly a reference to the Evsektsiia newspaper, Der Emes, which was the Yiddish equivalent of Pravda.

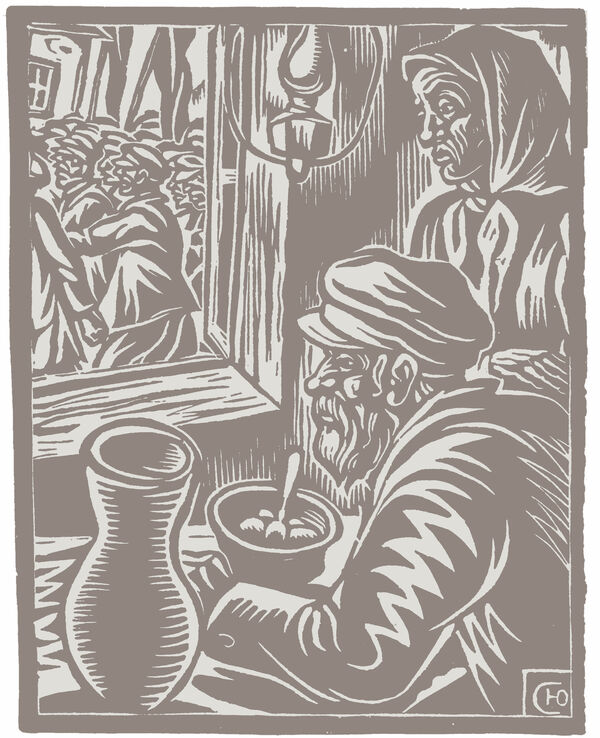

S. Yudovin: Untitled (Old couple looking through the window at a demonstration), 1929, woodcut

Indeed, there were prominent examples of religious Jewish socialists, as described by the Rebbe. Isaac Steinberg, a lawyer and political ideologue who wrote his doctoral thesis on criminal law in the Talmud, served as the people’s commissar for justice from December 1917 to February 1918. As the scholar Hayyim Rothman recently wrote, “anecdotal reports highlight the peculiarity of a high-ranking Soviet official donning tefillin each morning, or interrupting Lenin’s council meetings in order to recite the afternoon prayers.” Steinberg attempted to rein in political repression and stop “class enemies” from being outlawed en masse. His resignation marked the departure of one of the last dissenters in the Bolshevik regime, and with the dissolution of the Left Socialist-Revolutionary Party of which he was a member, he fled Russia in 1922.

THE ENDURING ASSUMPTION of a near synonymy between socialism and secularism is further complicated when we consider the oeuvre of the aforementioned commissar of education, Anatoly Lunacharskii. His 1928 attack on “the Schneersohnovschina” appeared in a speech on antisemitism, which he blamed on Jewish particularism. “The solution of the Jewish problem,” he proclaimed, “lies in the fusion of the Jews in the great melting pot of the peoples who inhabit the Soviet Union.” (Similar policies of assimilation and Sovietization were wielded against other ethnic and religious minorities. For example, Arabic script was banned in the Soviet Union, including in the five Muslim-majority Central Asian republics.)

Lunacharskii, in fact, had once been a serious student of religion. His two-volume Religion and Socialism—published in Russian in 1908 and in Yiddish translation in 1921—draws a line from Judaism to Christianity through to socialism. Although he was a materialist, he argued that the enthusiasm and warmth that animated religious life, together with its practical dimensions of prayer and ritual, should be transformed into a vehicle to rescue Marxism from the cold dryness of economic theory. In the words of the historian Dimitry Pospielovsky, Lunacharskii recognized that “a consistent regular atheist is a pessimist, because life becomes meaningless, ruled by death.” The solution he advocated was “religious atheism” according to which “you must love and deify the material world” and “the potentials of mankind.” For Lunacharskii, Marxism would not simply replace religion, but would actually become the religion of the future.

He rooted his ideology in Baruch Spinoza’s erasure of the distinction between God and nature, articulated in the excommunicated Jewish philosopher’s Ethics, published posthumously in 1677. “All the emotional power of Spinozism,” Lunacharskii wrote, “consists . . . in a deep, joyful giving up of one’s self to the world’s oceans.” Through contemplating the universe as a whole, the individual forgets everything that is particular to the self: “On the heights of pantheism all is turned into a single majestic chord, into one large sigh of an immeasurable all-blessed chest.” Spinoza’s collapse of God into nature provided Lunacharskii with a crucial element that could animate Marxist materialism with the spirit of religion.

At first blush, Lunacharskii’s Spinozist mysticism might appear to mirror Chabad teachings, which profess a profound vision of God as the singular reality, encompassing all things from the highest to the lowest. But Chabad’s theology relates to Spinozism only dialectically: As the scholar of Jewish mysticism Elliot Wolfson explains, Chabad’s erasure of the difference between divinity and nature entails the “divinization of nature,” which actually reverses Spinoza’s “materialization of God.” In the Chabad conception, God is not collapsed into the bounds of nature, but both fills the created cosmos and transcends it.

Still, the conflicting ideologies developed by Lunacharskii and by the rebbes of Chabad share a paradoxical intersection: In both worldviews, spiritual and material liberation are inextricably bound up with one another. Lunacharskii sought to turn religion into the handmaiden of Marxism’s materialist struggle for political emancipation. The Rebbe saw the ultimate significance of material and political freedom as the opportunity it provides for the emancipation of the soul and the sacralization of the world.

Riffing on a Talmudic aphorism that proclaims all Jews “believers sons of believers,” Moshe declares himself “a worker the son of a worker.” His faith and his proletarianism are intrinsically fused.

This intertwinement is captured, too, in the tragic figure of Moshe the carpenter, who finds himself trapped in the real-world crystallization of this ideological paradox. In his “eruption” in the aftermath of Berele’s speech, he sarcastically repeats the latter’s characterization of Pesach as “the freiheit [freedom] festival.” Indeed, Pesach celebrates the Jewish people’s emancipation from Egypt, traditionally referred to in Hebrew as “zeman chayrusainu,” “the occasion of our freedom.” But Berele’s term “freiheit” is no innocent translation of “chayrus.” It is, rather, an appropriation, transformation, and reduction of the religious quest for chayrus—“there is no chayrus but Torah” (Pirkei Avos 6:2)—into a political slogan. Berele doesn’t merely point to the resonances between traditional religious themes and the ideological fashion of the day. He instead advocates a political supersessionism, according to which “eating matzah, maror, and the like,” should be replaced with the generic rituals of “enlightened” secular culture (“a concert, with music and dance”). When Berele speaks of the laws of Pesach, it is not to inflect them with socialist significance but to belittle them and drain them of all meaning. Rather than facilitating chayrus, freiheit is weaponized to eradicate it.

For Moshe this is all an awful and incredible mistake. Chayrus and freiheit should complement each other rather than compete. Riffing on a Talmudic aphorism that proclaims all Jews “believers sons of believers,” Moshe declares himself “a worker the son of a worker.” His faith and his proletarianism are intrinsically fused, and he cannot abide the forced bifurcation of one aspect of his identity from the other: “I have always worked,” says Moshe. “I work now. And with God’s help I will continue to work from this moment onwards.”