I DIDN’T COLLECT THE BOOKS. Kate did. Decades earlier, she had gathered volumes of Yiddish literature and magazines from the elderly in Chicago and its nearby suburbs, and stored them in her living room. Now Kate was among the elderly. We became friends my first year as a teacher at the synagogue, where she also taught. I could rely on her messages late at night, the day before class. She thought of me, the newcomer to the congregation, when there was a death in the community, or when a student we shared was having difficulties, or when a shooting happened at a synagogue in another city. Once, we sat at her kitchen table for hours, surrounded by dusty boxes, while she gossipped about the Chutzpah collective, a leftist Jewish group she belonged to in the 1970s. I took notes. I returned what small favors I could. When I made kimchi, I brought her some. When she had a blocked artery, I prayed. When she asked if I could take the books off her hands, I said yes. It wasn’t urgent, she said, there were only a few.

Kate lived in an old red brick building a few blocks from me on the far north side of Chicago, near the lake. Two capacious apartments shouldered each other, stacked in triplicate. Carol, who’d been involved in radical Jewish groups in the 1970s and ’80s before moving to Chicago, lived upstairs. The building used to be a sort of cooperative; now just the two of them were left. One day, Kate called to tell me it was time for the books to go. She was renovating, and there was a building inspection coming up. I recruited a friend, Aviva, who also taught at the synagogue and owned a car. She drove a small, powder blue Honda, which I imagined had more than enough room.

A few days before the deadline, I ran into Carol at the University of Chicago. Irena Klepfisz, a poet and feminist critic, was giving a reading. I slipped in late. Soon, I was nodding along with her reading—the Yiddish sections of her bilingual poems sonorous and beyond my comprehension. I recognized Carol sitting a few rows ahead of me. I had sat at her kitchen table too, self-conscious about talking too much, sipping tea to slow my racing thoughts. Around Passover, she had given me her collection of Haggadot—all left-wing and homemade, spanning five decades. I found her when the reading was over. We had to talk about the books.

“You know it’s more than can fit in one car,” Carol said. I hadn’t known.

A few days later, I met up with Aviva and we drove together to Kate and Carol’s building. Kate’s apartment was unlocked. I’d described the place to Aviva on the way there, but I couldn’t really have prepared her. Dust and the smell of urine clogged our throats. Wallpaper peeled off the walls. On a bookshelf, a row of vinyl records had deteriorated, shedding cardboard pulp. Boxes were stacked in a pile in the living room. I called for Kate but heard no answer.

A minute later, she emerged from the backyard with a teenager from the neighborhood who was helping her straighten up her things. It was March, which in Chicago means snapping winter cold, punctuated with days of warmth. Outside, clumps of snow had begun to melt, revealing patches of muddy grass.

Aviva and I got to work. There were 16 boxes. I shoved a heavy one onto a small patch of uncluttered floor, tore through brittle newspaper stuffing, and held my breath. A rank cloud of yellow particles escaped into the air. I did this repeatedly, identifying which of these boxes were stuffed with Yiddish books. After two car trips, our throats were filled with phlegm. We talked about burning our clothes. The boxes themselves were disintegrating. One had kitty litter in it. We stashed them in the basement of my apartment building, then stood in my backyard breathing in fresh, cold air.

A MONTH WENT BY. My landlord threatened to throw out the “crappy books” in the basement if they weren’t cleared out in a matter of days. I made an arrangement. Another friend, a Slavic studies professor who sat on the board of the Chicago branch of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, agreed to take them. On a day when the ground was dry and the sun was out, I hauled the boxes into my backyard to dust off the books.

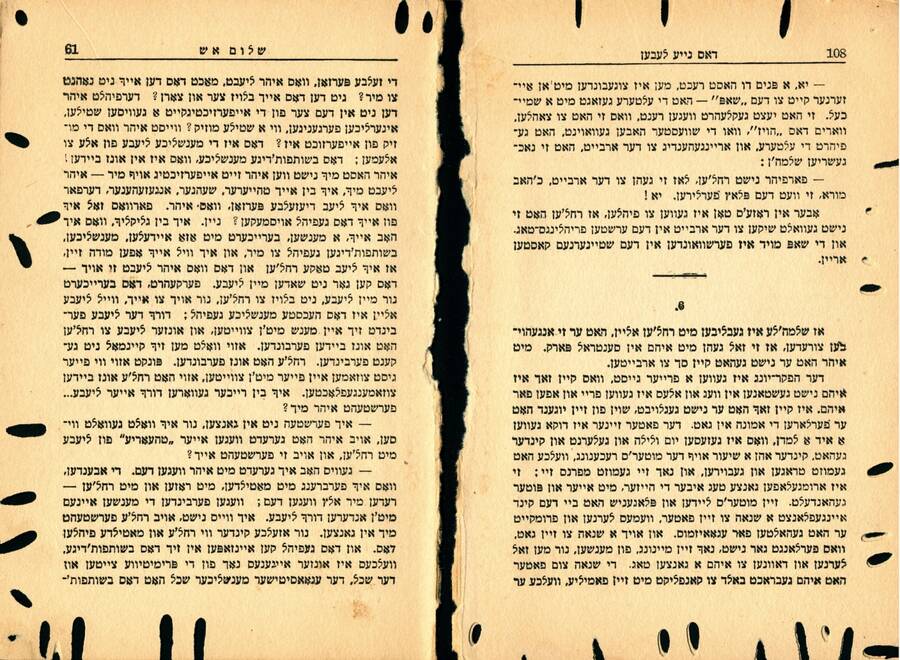

Yellow dust tumbled out of the pages; small clouds formed as I smacked each of the covers with my palm. White letters shaded with gold, almost every title in its own unique font. This was a literate language, I thought to myself, deep in the flow of stacking the books into fresh cardboard boxes and flattening the old, pulpy ones while holding my breath. At the poetry reading, Irena Klepfisz had quoted Czesław Miłosz: “Language is the only homeland.” I muttered the phrase now. If it was true, then I was certainly a stranger here. Often I puzzled over the titles, able to sound out the words, without making any sense of them. From a patch of grass nearby, a robin eyed the books.

One black book was covered in a chalky dust. Its sides were pockmarked with holes, like someone had taken a drill to its pages. I opened it up. Insects. Gray, rolly little dump trucks, nestled in the holes they had munched out of the margins. I poked one. It wriggled with life. I recoiled. Bookworms are real? I flipped through the pages, the strange, ovular holes cut symmetrically on either side. A few pages, a new hole, little incisions with insects tucked inside. Fascination overwhelmed disgust. The robin hobbled closer. I left the book, home to many insects, open on a bench. I got back to work.

For an infestation, the bookworms were respectful. They never ate very far into the text of the pages that they could not read. Most of the books were left unchewed, or only nibbled. Instead of bugs, I often found letters, stamps, and receipts between the pages. When my roommate wheeled their bicycle outside, I asked if they wanted to see the bookworms at home in the black book. We discovered two fern leaves, still bright green, pressed between the chewed up pages.

I DIDN’T KNOW IT at the time, but I had become a zamler, a book collector. Thousands have existed before me, both famous and nameless. Perhaps the most famous zamler of Yiddish books in the United States is Aaron Lansky, who went on to found the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Massachusetts. In his memoir, Lansky describes the night in the 1970s he received a phone call informing him of an emergency: in New York City, someone had discovered thousands of Yiddish books in a dumpster, as storm clouds gathered. Lansky scrambled from Western Massachusetts to the city. Rain had soaked the top layer of books. In the end, with the help of friends and strangers, five thousand books were saved. The dye from the covers stained the rainwater, which pooled at the bottom of the dumpster. In the world-saving act of collecting Yiddish books, there are hundreds, if not thousands, of stories like this. Some who save the books, like Lansky, are Yiddishists, and many others are not. Kate collected Yiddish books throughout her life that, like me, she could not read.

A zamler belongs to the world of books. In his essay on book collecting, Walter Benjamin illuminates the desires of such a person. “Every passion borders on the chaotic, but the passion of the collector borders on the chaos of memory,” Benjamin writes, inspired by the act of unpacking his library. He promises the reader he won’t bore them with stories about collecting books, but will dwell on the meaning of collecting itself. He can’t help himself, though; describing the way he acquired a prized book at an auction, he sounds like a person possessed. “Unpacking My Library” ends with a reference to an image from a German painter, Carl Spitzweg. In Spitzweg’s painting, a collector in his library looms precariously over a bookshelf from a ladder, books under each arm and tucked between his legs, others held open before his eyes. On the surface, the collector is a paunchy pedant. But Benjamin sees this hauteur as a mask: the collector poses as a snob in order to “carry out his disreputable existence” as a man who has decommodified his possessions by burrowing into them. There are spirits within him, “little genii”; or more precisely, Benjamin says, “it is he who lives in them.” Spitzweg’s painting is called The Bookworm.

A WEEK AFTER Aviva and I had rescued the books from Kate’s apartment, my grandfather passed away. His death was sudden, though his dying had been gradual. Before he was transformed by Alzheimer’s, he saved everything. I thought about him whenever I struggled to throw out a newspaper or clear the papers that cluttered my desk. Once, crawling around his study as a little kid, I was surprised to discover a sofa hidden underneath stacks of paper that seemed to almost reach the ceiling. As his Alzheimer’s worsened and he forgot who we were, he would still find hours of entertainment in a stack of old mail. I would put it in front of him, and he would sort through it again and again. Even after he lost his ability to read, he retained his love of paper.

My grandfather died in Florida. He was cremated, with a memorial service that followed after a hygienic gap of several months. When he died, I’d become briefly hysterical, appealing to my family in vain for a traditional Jewish burial for him: his body lowered into the ground within days of his death. It’s possible I’m a sentimentalist, that others more bluntly confront the hard facts of entropy, able to discard traditions and old books alike.

What happens when a collector dies? Or when a collection is buried in the trash, undiscovered in a dumpster? What part of the world relies on those Yiddish books not being destroyed? I still do not know. They could be thrown out, and no one would miss them. Almost no one knew they were there in the first place, except for the bookworms, who lost their homes when the books were saved.

I brought Kate’s books—cleaned off and packed into fresh boxes—to a storage facility with the husband of my friend from YIVO. We arrived at his locker and stacked the boxes alongside others, no doubt also containing books. He pulled the retractable door closed. The echo from its shriek reverberated then sunk into silence.

Dedicated to Kate Kinser, who passed away on the 29th of Tevet, 5780 (January 26th, 2020). Her memory is a blessing.

Isaac Brosilow is a contributing writer for Jewish Currents and an independent researcher from Chicago, currently based in Brooklyn. His work has appeared in Protocols and Graylit.