Structuring Voids: Jenny Yurshansky’s Malleable Monuments

Jenny Yurshansky’s work explores the search for clarity in the impossible face of trauma.

ILLUSTRATING THE WAYS in which political borders affect the landscape is a preoccupation of Los Angeles-based artist Jenny Yurshansky. Her multi-year project Blacklisted: A Planted Allegory explores how plants become “blacklisted,” deemed dangerous intruders on the landscape; it’s taken many forms, including audio, installation, and most recently, an artist book. In these works, fear around non-native plants as destructive to a “pure” national landscape is both a metaphor and a perspective historically intertwined with xenophobic anxiety towards outsiders. Yurshansky’s work asks us to consider how cultures of division impose themselves on the natural landscape, and how cultural and ecological landscapes regenerate across the violent scars caused by borders.

While her lived experience as a refugee is present in Blacklisted, Yurshansky foregrounds it in her most recent body of sculptural work, Crusted Memory, where she has turned directly to her family’s history of displacement. Yurshansky’s grandmother successfully fled a Nazi death squad in Moldova; her parents fled the USSR decades later. She was born in Italy en route to the United States, technically stateless at birth. She has only slivers of stories about her family’s life under antisemitic authoritarian regimes during WWII and Stalinism. Crusted Memory explores the search for clarity in the impossible face of trauma.

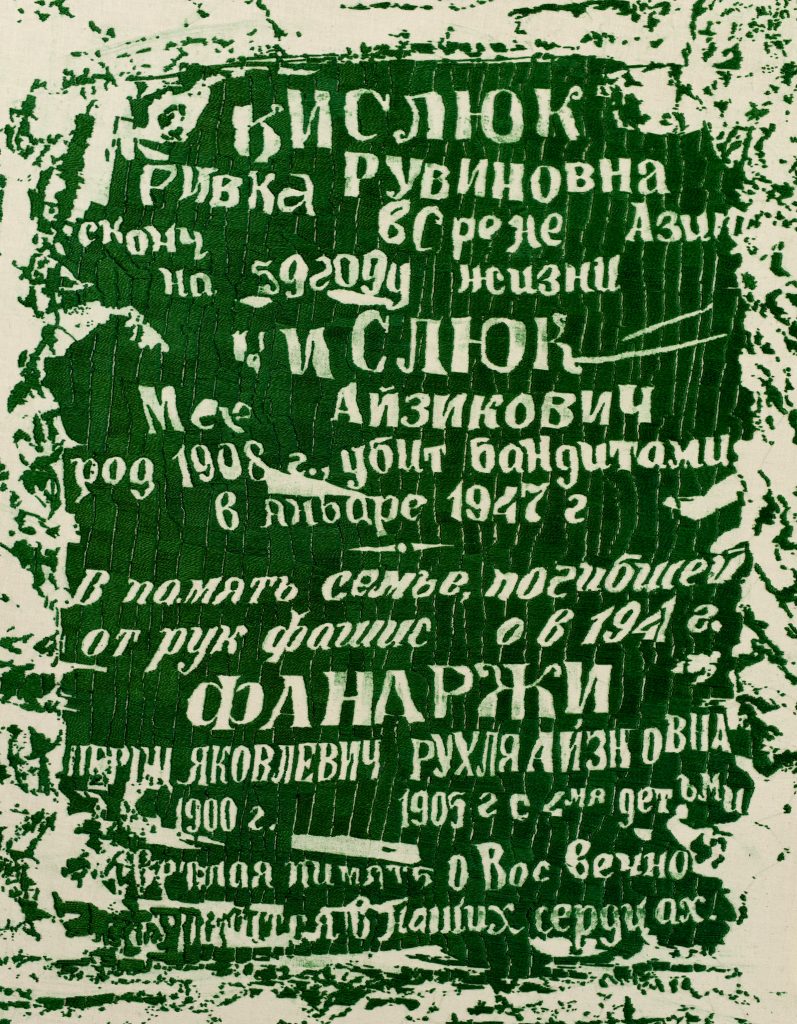

Knowing that much will remain unknowable, Yurshansky traveled to Moldova to research her family history. Her mother reluctantly agreed to accompany her. In visiting a cemetery where many Jews were buried, they discovered a 12-foot-tall headstone memorializing her great-grandparents and great-aunt and -uncles. But only her great-grandfather, who died before the war, is actually buried there. Her great-grandmother died in exile in Uzbekistan; her great-aunt and -uncle and their four children were all murdered by fascists in 1941, their bodies never recovered. The headstone, a limestone carving in the shape of a limbless tree, had been painted green and completely overgrown with wild vines. The groundskeeper explained it had been painted and untended in order to prevent vandals from looting the stone for building material, an explanation that did not sit well with Yurshansky’s mother. She assumed the overgrowth was a symptom of neglect. Like many aspects of her family’s story, the truth remains obscured.

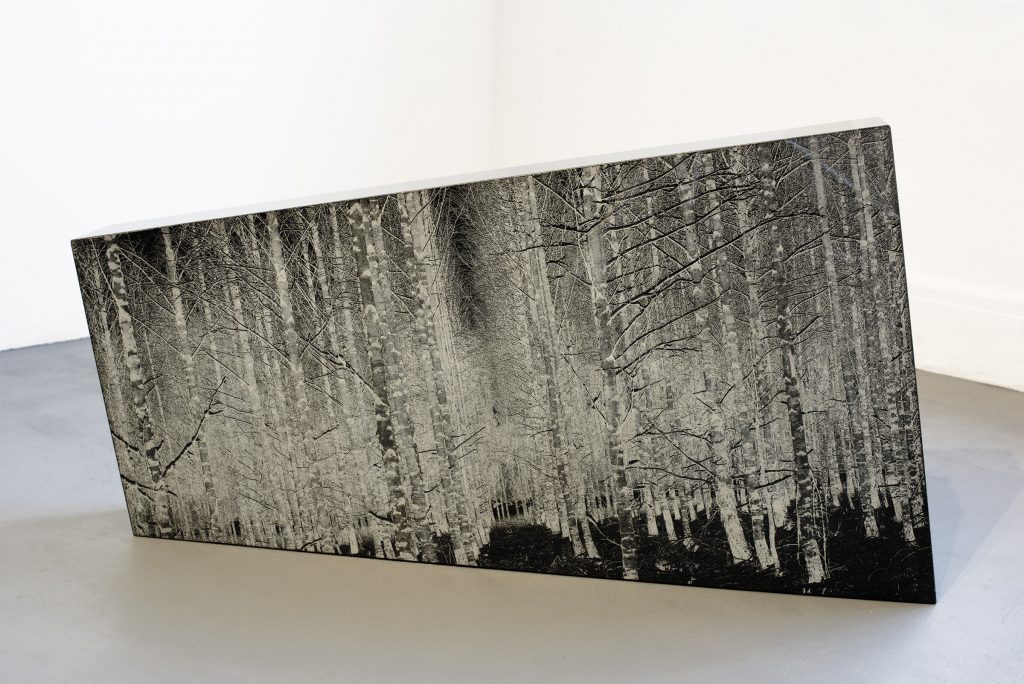

Encountering the headstone crystalized connections between the artist’s distinct bodies of work. The relationship she had been exploring for years, between ecological destruction and xenophobia, became visible in unexpected ways. In a place where borders had been drawn and redrawn multiple times in the course of her family’s history, the vines on the headstone served as a living reminder of earth as its own subject rather than an object to be marked up. And there were other uncanny discoveries. Prior and unrelated to her trip, she created a piece entitled Succession, a slanted headstone made of black granite and etched with a photograph of a forest. The work, which referenced the creation of single crop forests in Sweden for the express purpose of making ships for war, was intended to speak to the human desire to control nature. In the Moldovan cemetery, she learned that the shape of headstone she fabricated is actually typical to Jewish cemeteries there—the dramatic slash signifying a life cut short. She wrote in an artist statement, “It was a very unsettling discovery . . . feeling that somehow I had carried this knowledge in the recesses of my mind through someone else’s memories.” These connections surprised and confounded Yurshansky. She decided to return to the cemetery to make a scaled rubbing of the headstone. The laborious act of tracing the monument could not reveal what was lost, but created a surface for the artist to literally work through her cross-generational feelings of displacement.

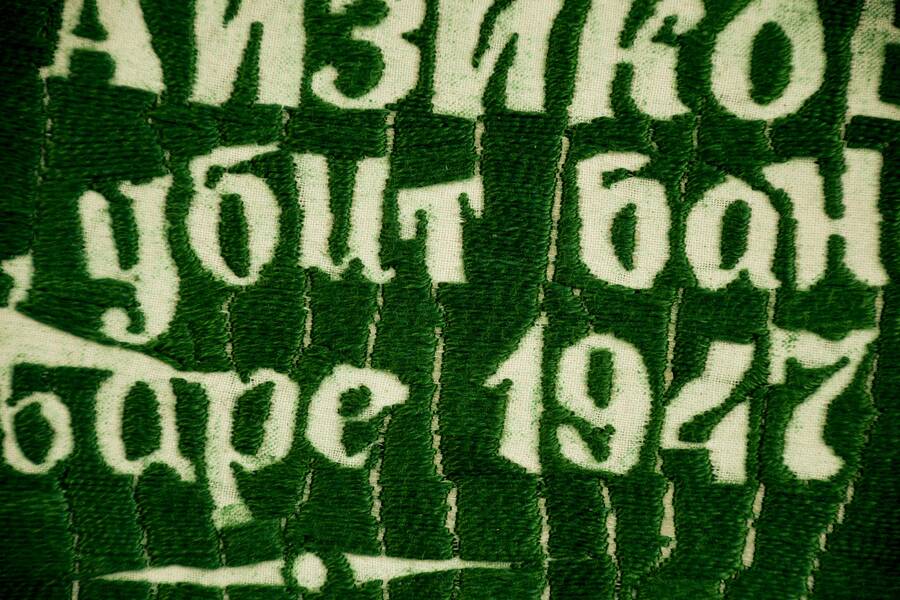

As Yurshansky told me, she owes her life to sewing. Fleeing almost 3,000 miles from Moldova to Uzbekistan, her grandmother was able to survive in part because of her sewing abilities. Inspired by this story, embroidery became the obvious medium for Yurshansky to treat the material from Moldova. The headstone rubbing was made on dressmakers’ muslin, a material not typically meant for public display, as an homage to her grandmother’s labor. Together with her mother, she embroidered the cloth with forest green thread. The thin fabric is heavily worked upon, a reference to her own experience of returning again and again to fragmented stories.

The headstone rubbing became part of a sculptural installation of Crusted Memory entitled A Legacy of Loss. In preparing for the installation, the artist discovered another material, which functioned as an ideal metaphor for her experiences—precision glass blanks, used mostly in the creation of prescription lenses. She writes, “the contradiction of a lens that is meant to help one see more clearly being precisely blank is a foil to the difficulties with memory that refugees have . . . the blank spots that exist in what is shared and remembered as a result of trauma.” Blank spots in Yurshansky’s history become structuring voids upon which everything else is built. The sculpture looks like a forest made of glass and wire: light passes through the glass and dances across the gallery. The headstone rubbing becomes sculptural, folded into the installation, creating an obscured and malleable monument. It seems almost as if it’s been swept up by a breeze and suspended in unreachable branches.

Photo: Alexandra Pacheco Garcia

Yurshansky is aware that her work is timely. What is most striking to her is that it always has been. In each iteration of Blacklisted, she’s been able to trace connections between her exploration of the landscape and ongoing anxiety about otherness, from the destruction of Palestinian olive trees in Israel/Palestine to the deeply felt impacts of the US-Mexico Border in California. Searching for her own roots through Crusted Memory has connected her more deeply to issues of displacement and forced migration happening in the United States and around the world. As her newest work demonstrates, historical memory is often obscured by the powerful psychic forces of trauma, but it lives on in the landscape and in our bones.

Martabel Wasserman is an artist, writer and curator living in Santa Cruz.