Reclaiming a Minor Literature

The editor of diasporic Hebrew journal Mikan Ve’eylakh seeks to recover the possibilities of Hebrew language not tied to the State of Israel.

Last October, the bestselling novelist Sally Rooney announced that she would not be selling the translation rights for her latest novel to an Israeli publishing house, in line with the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement’s call to boycott cultural institutions complicit in Israeli apartheid. Although Rooney made clear in her statement that she would be “pleased and proud” to publish her book in Hebrew if she could do so in a way that aligned with her support for Palestinian rights, her decision was initially misreported as a “boycott of Hebrew,” prompting accusations of antisemitism. Critics of Rooney’s decision rushed to collapse her careful distinction between language and state: The translator Yardenne Greenspan told The Forward that “since Israel is the lingual and cultural center of Hebrew literature, a decision to boycott Israeli publishers is, de facto, a decision to boycott Hebrew.”

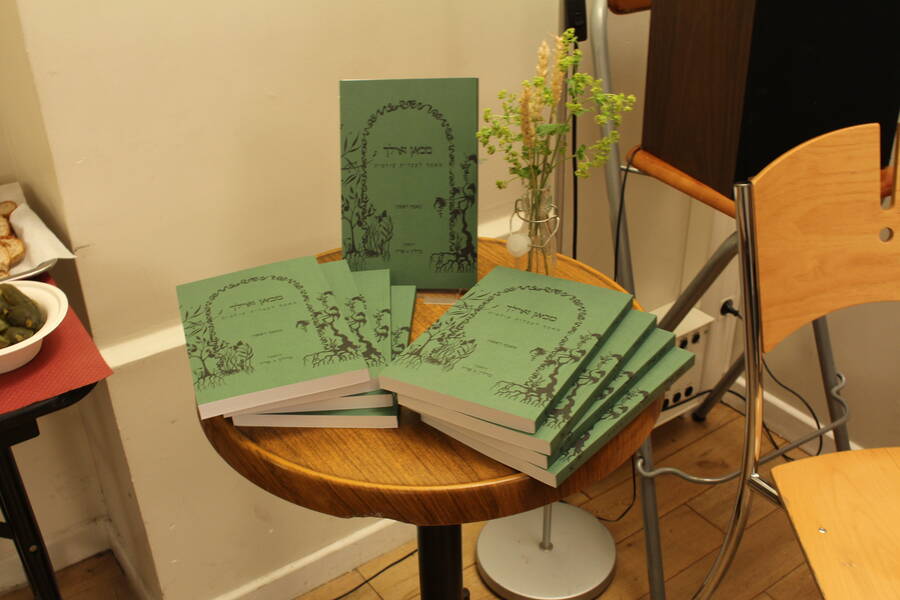

Greenspan is not wrong that the vast majority of Hebrew literature is currently oriented around the State of Israel, but alternate visions do exist. Reclaiming a “diasporic Hebrew” is the determined project of Mikan Ve’eylakh (“From Here Onwards”), a literary journal founded and edited by Tal Hever-Chybowski, director of the Paris Yiddish Center—Medem Library, the largest Yiddish institution in Europe. Mikan Ve’eylakh’s two issues (a third is in the works) are filled with Hebrew texts that conceptually, thematically, and politically look beyond the territorial constraints of the State of Israel, including articles, poems, and stories from a wide array of academics, intellectuals, and writers. The journal’s two issues, published in 2016 and 2017, have included, for example, an article on “Arabic World Hebrew” by the scholar Mostafa Hussein, a Hebrew translation of an Edward Said essay on intellectual exile, stories by the French historian Maurice Olender and the deceased Yiddish writer Avrom Reyzen, and poetry by Berlin-based poet and professor of Talmud Admiel Kosman. Hebrew, in Mikan Ve’eylakh’s pages, is not solely the language of an ethnonationalist regime or the idiom of occupation, but something far more capacious, rich, and multi-layered, described more accurately by its discontinuities than its continuities, its minority status than its might.

While much work has been done by the Jewish left to free Jewish practice, history, and texts from the grip of Zionism, the language that Jews have spoken, read, and written for thousands of years around the world sometimes falls by the wayside. For Hever-Chybowski, such an abandonment would be too great a loss to bear. I spoke with him about his vision for Mikan Ve’eylakh, his conception of diasporic Hebrew, and the relationship between Hebrew and nationalism. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Maya Rosen: When did you first become interested in diasporic Hebrew?

Tal Hever-Chybowski: I grew up in Jerusalem, and at the age of 21, I decided to leave the State of Israel and move to Berlin, because I didn’t want to start my life in Palestine-Israel. The first identity crisis I faced was the question of what to do with the language. Like so many other Israelis, I felt that Hebrew was so bound up with the State of Israel that I either had to come to terms with that or move on and find ways to create, write, and think in other languages. I realized that neither option was a price I could pay.

I began working on Mikan Ve’eylach in 2009, one year after my immigration to Berlin. It became clear to me very quickly that I was not inventing the wheel. Hebrew has been present in Europe for more than 2000 years. Everything that I know as Hebrew—modern Hebrew, modern Hebrew literature, modern Hebrew periodicals, Hebrew publishing houses—was invented in Europe. At the beginning, my research was about dispelling a lot of the myths that I grew up on: that Hebrew was somehow a dead language that suddenly was reborn or revived like Jesus, in Palestine. At least in the beginning, there was a lot of anger that there were things I was taught not to know.

In about 2011, I realized that to understand what it means for a Jewish language to be diasporic, I needed to learn Yiddish. I needed to ask what Yiddish could teach me about diaspora. Mikan Ve’eylakh came to fruition only in 2016, two years after I moved to Paris to direct the Paris Yiddish Center—Medem Library, which publishes Mikan Ve’eylakh. When Hebrew can consider Yiddish as its host, when Hebrew is hosted in Europe by a Yiddish publishing house, then you have diasporic Hebrew.

MR: Who was the intended audience of Mikan Ve’eylakh?

THC: The first audience was my future children. I don’t have children, but the project came into being with this idea that there aren’t any contemporary Hebrew texts that I would feel comfortable teaching my future children. All Hebrew literature being written today is written from the perspective of the negation of the diaspora. It’s written to a public that sits in a cafe in Tel Aviv; it’s written to a public that knows exactly what’s going on in the State of Israel. This is the starting point that Mikan Ve’eylakh tries to change by creating a different corpus.

MR: How do you choose what to publish?

THC: I was never interested in the question of where a writer is from. People can write from Tel Aviv. It’s a question instead of where the writing is directed. 99.99% of the texts that are written in Hebrew today, including the texts that are sent to me, were clearly written with an Israeli public in the State of Israel in mind. It’s almost impossible for writers in Hebrew to step back and to imagine a readership that is diasporic, that is scattered, that is not in the State of Israel. This is not to say that the Hebrew of Mikan Ve’eylakh is a non-Israeli Hebrew. It’s impossible to write in Hebrew and not be influenced by the idioms and syntax of where Hebrew is and has been for the last 80-plus years. There is no negation of where the center of Hebrew letters is; there is no make believe.

MR: What is the relationship between Israeli Hebrew and diasporic Hebrew?

THC: “Israeli Hebrew” and “diasporic Hebrew” are not antagonistic terms. Israeli Hebrew is within diasporic Hebrew—because diasporic Hebrew is eternal, and all Hebrew is diasporic. Diasporic Hebrew will never cease to exist, whereas the State of Israel will cease to exist at some time or another, and Israeli Hebrew will cease to exist at some time or another. And then the corpus that has been written and produced in the State of Israel will become a very big and important chapter of Hebrew at large.

There is also an anti-diasporic Hebrew. It too belongs to diasporic Hebrew, but ideologically, it tries to negate the diasporicity of Hebrew. For example, there is something that I call hay shlilat ha’galut—the use of the letter “hay” (the definite article in Hebrew) to negate the diaspora; for example, ha’aretz (“the land”), ha’tzava (“the army”), ha’tikshoret (“the media”). This “hay” conveys the idea that all the other armies in the world, all the other governments, all the media, all the countries, anything else you might want to speak about, need to be specified. If you don’t specify, you mean the only valid place in which Hebrew is a language, which is the State of Israel. And this is something very new and modern. To be clear, referring to the land of Israel as ha’aretz is indeed historically founded, and the land of Israel has been called the short form ha’aretz for centuries. The new thing is that it became impossible to talk about any other land as ha’aretz—which was not the case a hundred years ago, or even less. For example, for the audience of 19th-century Russian Hebrew newspaper Ha’melits, there would’ve been no question that ha’aretz could refer to Russia in certain contexts. So the new thing is not so much what Hebrew forces you to say so much as what modern Israeli Hebrew no longer allows you to say.

MR: In the Hebrew subtitle of Mikan Ve’eylakh, you use the term “Ivrit olamit,” (“world Hebrew”), which is not a direct equivalent of the English subtitle “diasporic Hebrew.” What is captured by the word “olami” that is not captured by “diasporic”?

THC: “Ivrit olamit” and “diasporic Hebrew” are not the same thing, but I think that they are complementary. “Olami” can be translated as “world,” and it can also be translated as “eternity.” Historically, the term has this duality of space and time. Simon Dubnov, maybe the greatest modern Jewish historian, translated the title of his history of the Jewish people into Hebrew as Divrei Yamei Am Olam, or the history of “the world people,” the people scattered throughout the entire world, and also “the eternal people.” Part of what I have tried to do with Mikan Ve’eylakh is to say that diaspora is not only in space; diaspora is also in time.

MR: What does it mean for there to be diaspora in time?

THC: The word “diaspora” is an intervention against the expectation of continuity. The simplest way to understand “diaspora” is in terms of national continuities—there are territorial continuities in, for example, a nation-state: This is Germany, a kilometer to the west is also Germany, a kilometer to the east is also Germany, and this territorial continuity makes this Germany. Diaspora, in terms of space, is defined precisely by the gaps between these points of continuity. If we think of diaspora as a situation in which language, culture, and people are scattered in many different spaces, there has to be a gap between the points; without gaps or discontinuities, it is not diaspora.

Diaspora refrains from imagining a unified or global continuum. Think of a chain or a net; chains and nets contain or connect things, but a chain is defined by the gaps between the links. No gap, no chain. These visual metaphors can also be applied to time: You have this ideological myth, according to which Hebrew simply died, and then Eliezer Ben Yehuda [who is often credited with reviving Hebrew for the modern Zionist movement] taught his son the language, and Hebrew was revived. And there is another myth that tries to argue precisely the opposite, that Hebrew has had historical continuity without gaps: In every moment in world history, Hebrew was not only written but also spoken. And I think that this extreme binary negation of the myth of death with a new kind of myth of organic continuity is very fragile. What I mean by diaspora of time is that we can accommodate gaps and discontinuities. We can accommodate even the narratives where Hebrew was spoken somewhere and then died out. Why don’t we accept that Hebrew can be scattered in time and adopt a more nuanced understanding of culture, literature, language, and civilization that is not based on this very fragile concept of an organic continuum?

MR: What do you see as the political stakes of separating Hebrew from sovereignty?

THC: The main vehicle of Mikan Ve’eylakh is reflection and deconstruction, making explicit things that are hidden and implicit. It’s an attempt to subvert this implicit connection that Hebrew and the State of Israel are one and the same. The main way to do this is historically, meaning understanding that, for centuries, the reality of Hebrew was different. In a way, I think Mikan Ve’eylakh is not so much trying to proclaim a new kind of Hebrew as it is trying to unearth previous paths that have been covered up and blocked.

I have blamed Zionism for quite a lot of things, but we should also speak about the khurbn, the Holocaust. The Nazis, first and foremost, were the ones who removed Hebrew from Europe. And to go back and say, “Wait a second, there was Hebrew here,” is also to defy violence. I’m most interested in the political statement that Mikan Ve’eylakh has vis-a-vis Europe, this place that rejected and killed its Jews. To recreate Hebrew culture, to recreate an opportunity for Hebrew literature in Europe, is first and foremost an intervention in this history.

MR: Elsewhere you have talked about Y.L. Peretz’s discussion of the “dialectics of liberation and oppression,” and you quote Peretz’s line, “you have to fight for the rights of the oppressed but I tremble the day that they will get power, the moment when the oppressed will become the oppressor.” How does this line relate to Mikan Ve’eylakh’s project?

THC: This is one of the key themes that interests me. I cited Y.L. Peretz, but it was also articulated even earlier, in 1904, by Vladimir Medem, the most important political thinker of the Bund, the socialist Jewish movement that was founded at the same time as the Zionist movement in 1897. This warning calls for a lot of care in any kind of political or cultural activism. How do you make an intervention in discourse, knowing that any kind of change in power structure can be co-opted and appropriated and lead to new oppression? I don’t have all of the answers, but one way is not to aim for victory, not to understand liberation in terms of seeking sovereignty, power, and the upper hand. From the very beginning, the project of Mikan Ve’eylakh was not just about reclaiming diasporic Hebrew but also reclaiming it within an understanding of Hebrew as a minor literature and as a minority language. There was no manifesto for Mikan Ve’eylakh; there was no “ten steps for how to liberate Hebrew.” These are all political strategies that tend to be co-opted and become instruments of oppression. The fact that Mikan Ve’eylakh is published under a Yiddish publishing house is also a way of articulating that there is no attempt here to reclaim Hebrew as powerful performance.

MR: What is your vision for Hebrew’s future?

THC: My vision for Hebrew’s future is very similar to Hebrew’s past. I do not fear for Hebrew. Aramaic, for example, is no longer spoken by Jews but will never cease to be a fundamental component of Jewish life because of its presence in some places in the Hebrew Bible and throughout the Babylonian Talmud. I speak Yiddish fluently, but I’m not afraid of the day when there are no fluent speakers. I think that Yiddish has such an incredible corpus of literature, both in quality and in quantity, that it cannot be discarded. And so I don’t think that Hebrew is in any kind of peril. Hebrew is an eternal language in the sense that all previous and future utterances of Hebrew continue to reside in it. It’s not like Hebrew exists in one time; Hebrew exists in many times in parallel.

There are of course differences between Biblical Hebrew, Mishnaic Hebrew, Medieval Hebrew, and the Hebrew that we speak now. And yet I am convinced that if the 11th-century rabbinic sage Rashi were to sit with us now in a cafe, it would take him only about two hours to fine tune his ear to be able to converse with us. I would know which words to avoid, and he would know which words to avoid, and we would be able to talk. I’m sure of it, because Hebrew is a language that is based on a shared literary corpus and because that literary corpus is cumulative. So the future of Hebrew is like the present: It will keep accumulating and never cease to exist.

Maya Rosen is the Israel/Palestine fellow at Jewish Currents.