Comic / “To Hell with This Depressing Atmosphere”

Amid the height of the 1960s counterculture, underground comix offered an unprecedented space for free expression—if you were a man. Artists like Robert Crumb, Gilbert Shelton, and Kim Deitch drew their way to notoriety, pontificating, hallucinating, and (figuratively) masturbating on the page. These weren’t the newspaper strips or kids’ comic books of the preceding decades, with their long-running gags or moralistic stories about superheroes. The new comix were experimental, sexual, political, and weird—as suggested by the “x” that hung on the end, like a rating or warning. They were also—at least at times—openly misogynistic. Women were more likely to appear in their pages as the bare-breasted objects of someone’s desire than as full characters, let alone creators.

That began to change in 1970, when the cartoonists Trina Robbins and Barbara “Willy” Mendes compiled It Ain’t Me, Babe, the first comics anthology devoted entirely to women. The cover, drawn by Robbins, featured beloved female pop-culture characters like Olive Oyl, Wonder Woman, and Sheena, Queen of the Jungle, marching angrily beneath the words “womens [sic] liberation.” It Ain’t Me, Babe opened the door for more efforts to follow, including the long-running and critically acclaimed Wimmen’s Comix, another Robbins collaboration that launched in 1972.

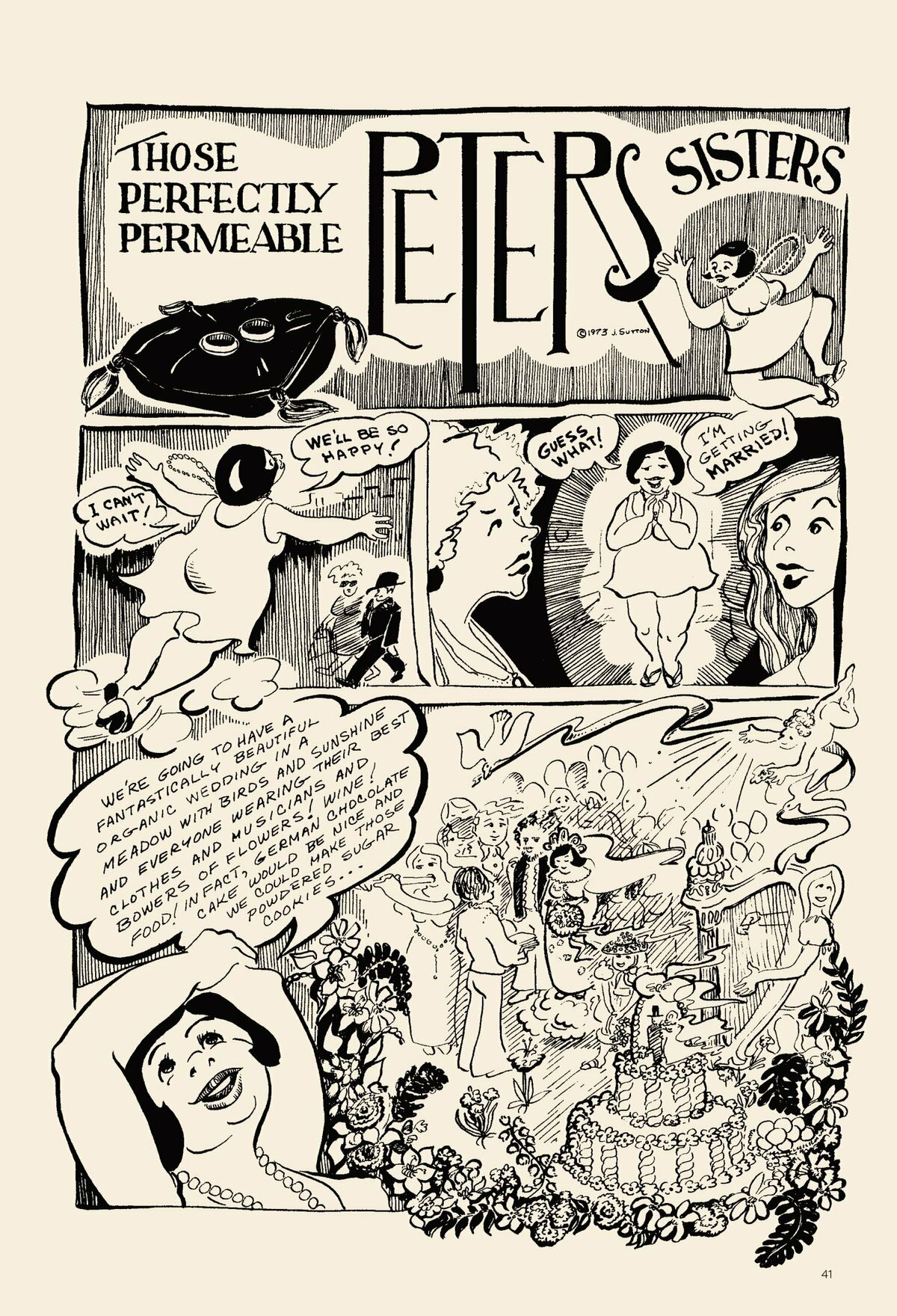

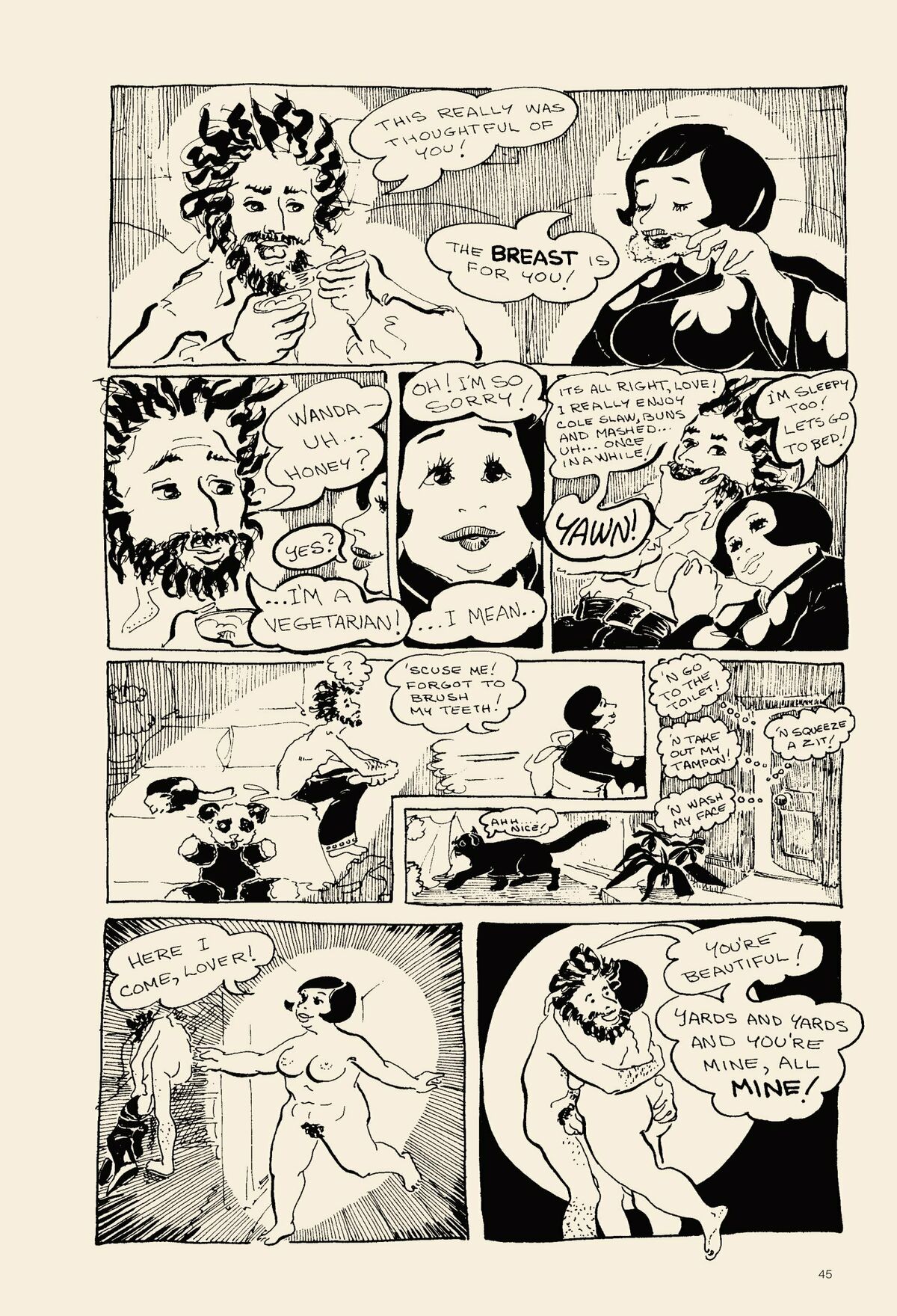

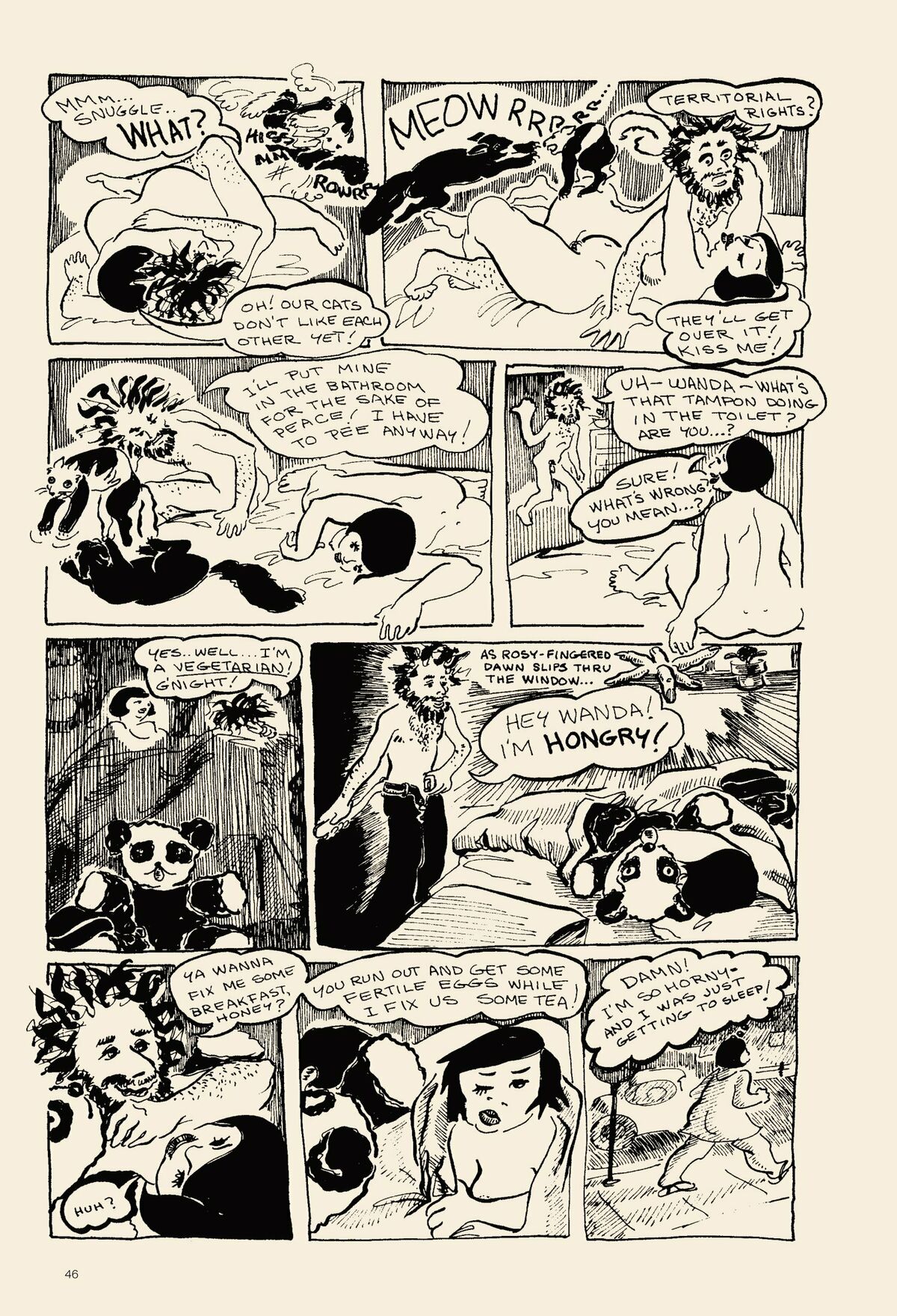

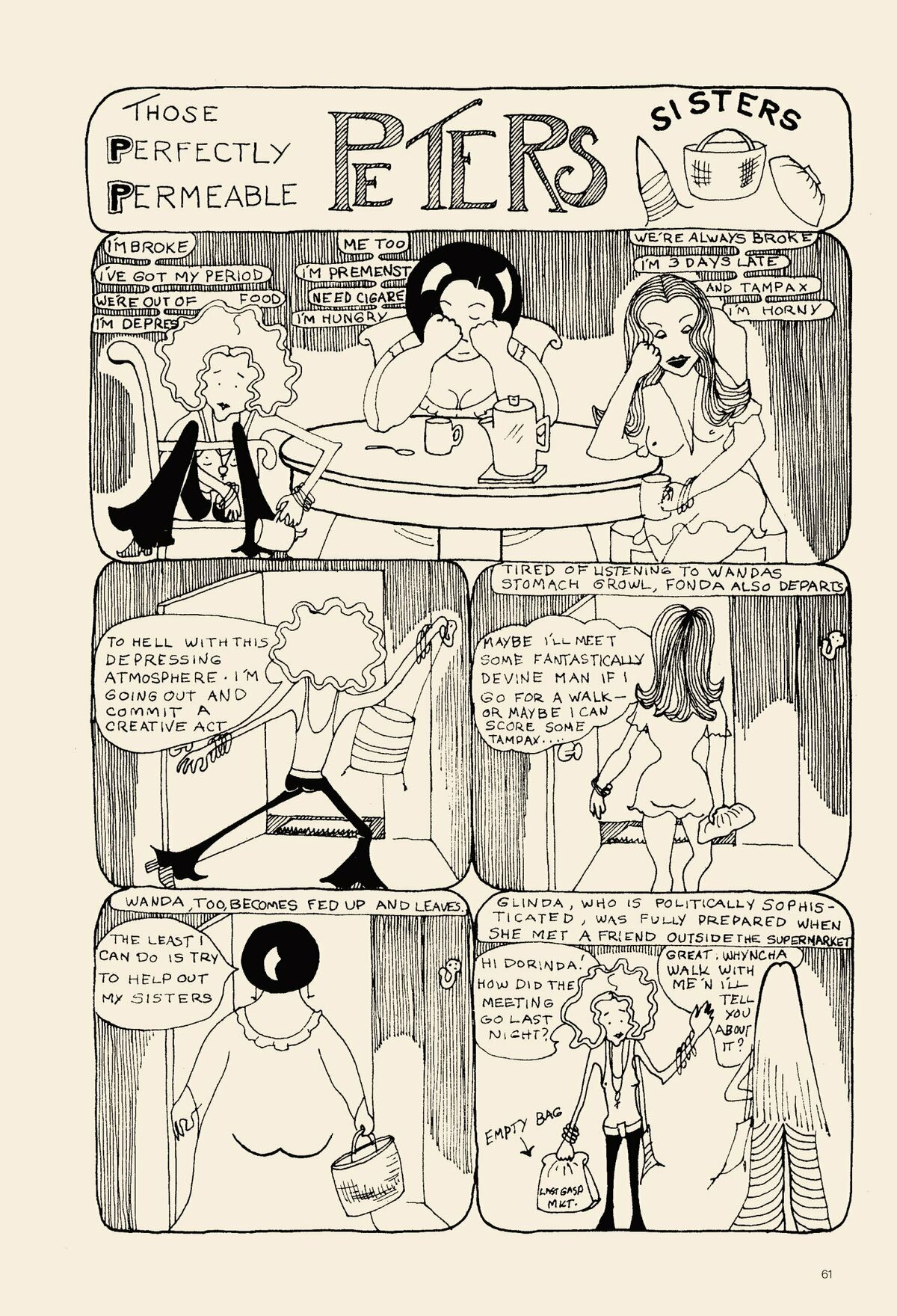

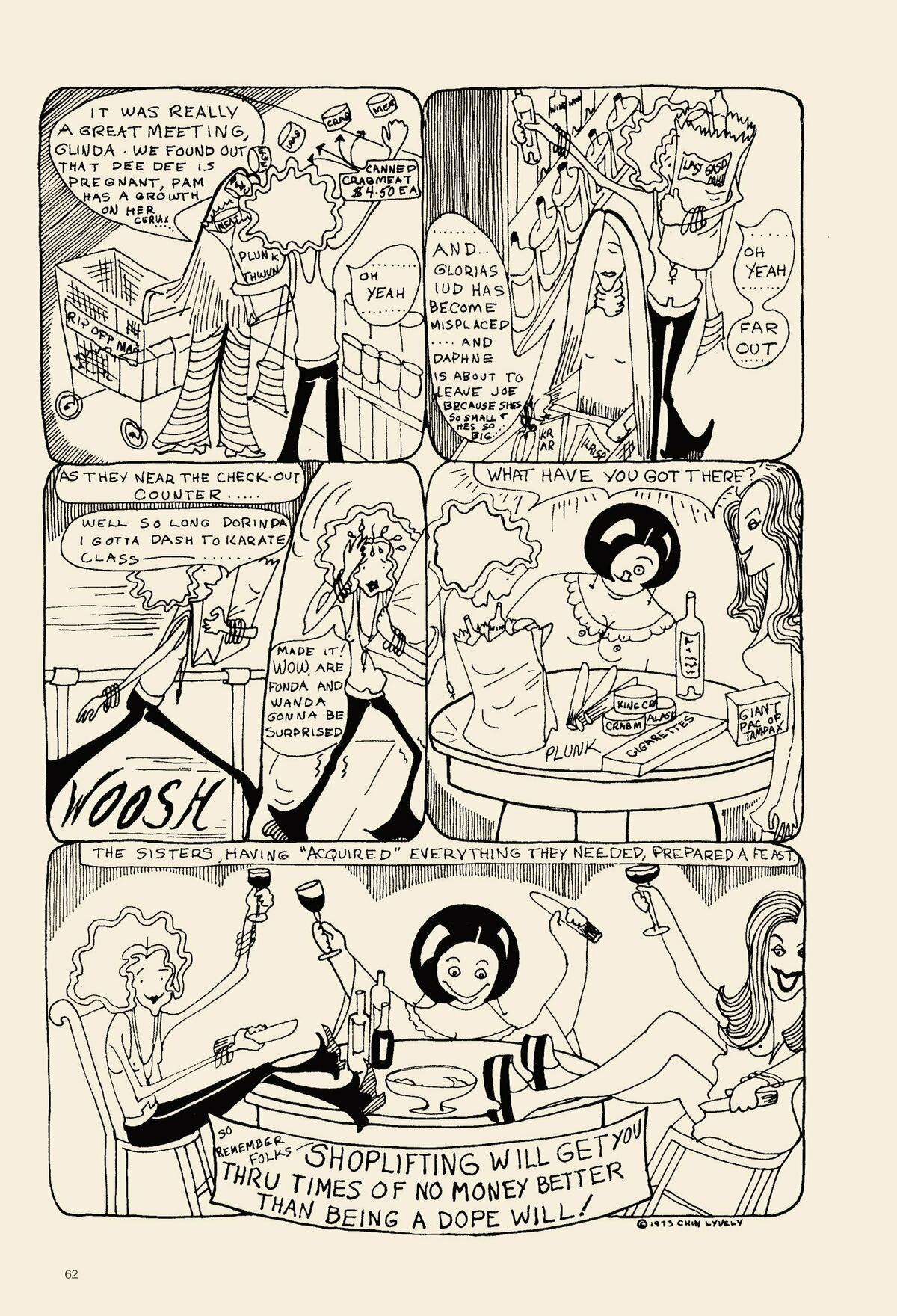

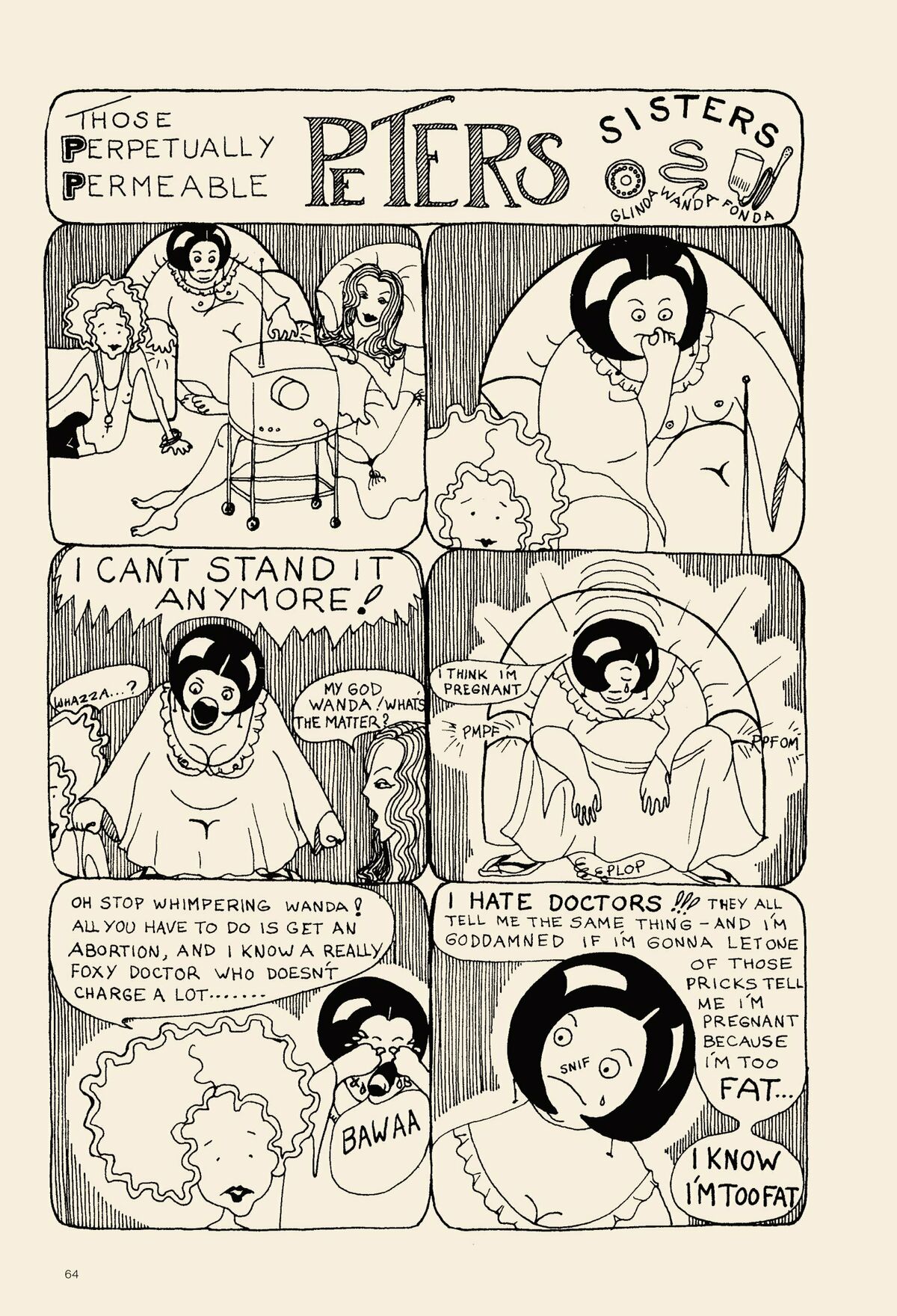

Perhaps the most risqué of the new women’s anthologies was Tits & Clits, released the same year and edited by Lyn Chevli and Joyce Farmer. Chevli and Farmer were newcomers to the underground scene, but like Robbins they saw a void, not only of women’s comix generally, but also of frank discussions about women’s bodies and sexuality. Tits & Clits sought to fill that space with comix that tackled subjects ranging from menstruation to masturbation. In its pages, women had psychedelic pleasure sessions with plants and raucous orgies with attentive partners; hijinks ensued as mothers tried to find private time to get off or let their kids borrow their vibrators. The anthology could be serious, as with an educational issue titled “Abortion Eve,” but its recurring characters were just as often fantastical, like the mischievous, medieval “Sisters of Barrow,” or absurd, like “The Bosomic Woman,” a parody superhero with impossibly large breasts.

The anthology ran for seven issues, with two additional standalone releases, over the course of 15 years. It was a resolutely DIY project, moving forward in fits and starts while dealing with a chronic lack of funding, government anti-obscenity crackdowns, and condemnation from the anti-pornography wing of the women’s movement. (Chevli also left the partnership in 1980 due to creative differences, and Farmer went on to edit the final issue with Mary Fleener.) The work was both propelled and limited by the way that Chevli and Farmer, at least initially, took the model of men’s underground comix and flipped it. To them, “male portrayals of sexual fantasy and sexualized violence in underground comix were more or less equally offensive,” Samantha Meier writes in the introduction to Fantagraphics’s recent collection of all the issues of Tits & Clits. “Yet they also represented expressive possibility.” The results of the pair’s efforts to claim space in the genre were not always feminist in readily legible ways. The quality of the content was also mixed—the duo’s lack of experience showed in the early editions. And, as is true of much material that came out of the second-wave feminist movement, the series tended to represent the perspective of cis, straight, white women, which constrained its depth and appeal.

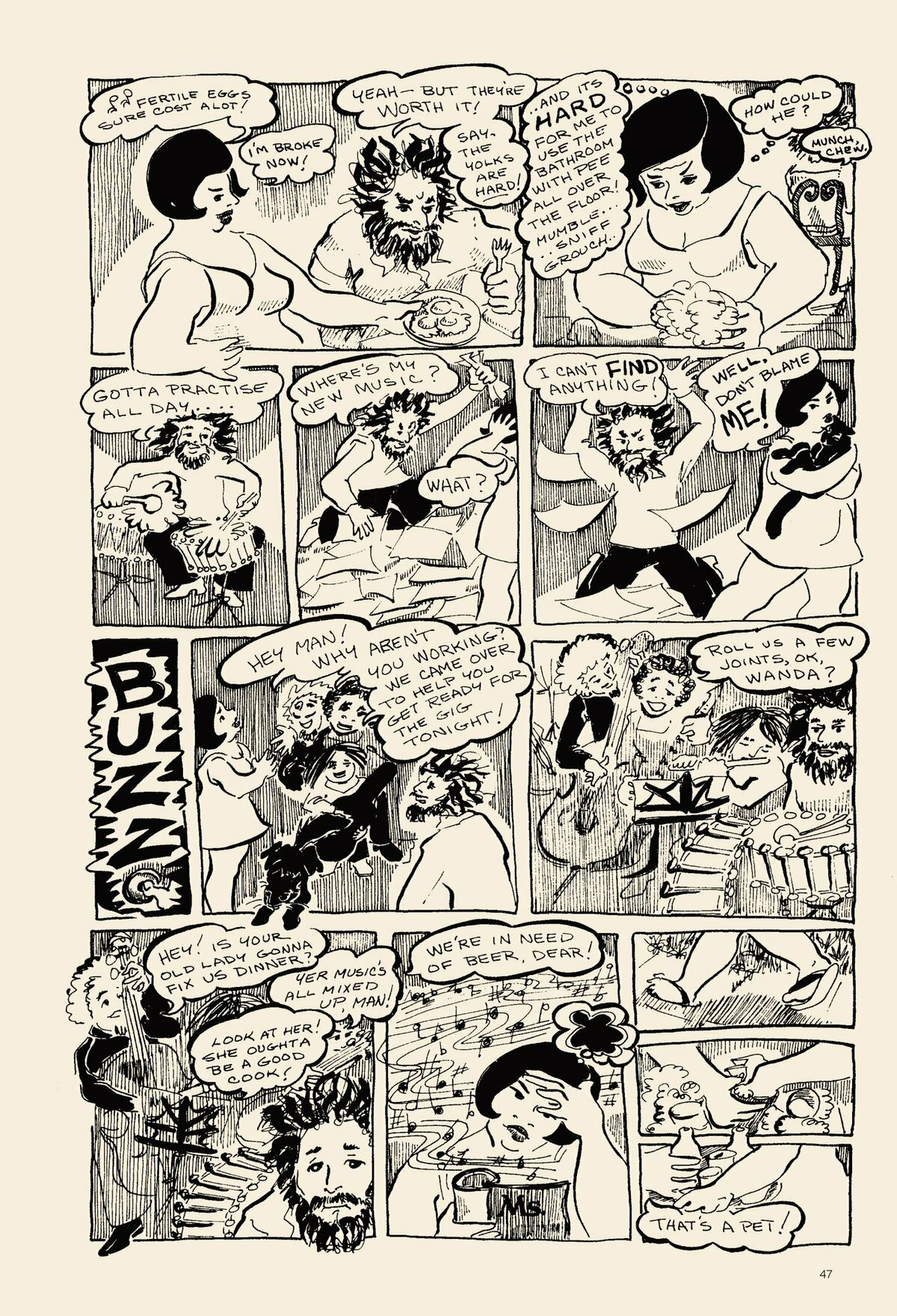

And yet, reading Tits & Clits today, I find its inventiveness and unabashed commitment to dirtiness exhilarating—there’s liberation in being unafraid of bad taste or taboos. It’s hard to imagine many of these comics being published now, when personal experiences have become a more valuable cultural currency than fantasy, the stakes of giving offense have gotten higher, and society seems more concerned with the uses and abuses of sexual power than with pleasure. The gratuitous sex and transgressive attitude of Tits & Clits also stand out starkly against a backdrop in which women’s bodies—and the bodies of trans and gender-nonconforming people—are subject to an even more punitive social and legal regime than they were in the 1970s.

One of Chevli and Farmer’s more down-to-earth creations was “Those Perfectly Permeable Peters Sisters,” a recurring feature about a sibling trio who struggle with deadbeat men, late periods, and being broke. Below, we’ve reprinted three “Peters Sisters” comics from 1973, alternately drawn by Farmer and Chevli in different styles. Like many of the female characters who appear in the pages of Tits & Clits, the Peterses have real, relatable problems, which are recounted candidly but with a light, witty touch. In the face of their travails, they remain irreverent. One sister captures the anthology’s spirit on her way out the door to shoplift some food. “To hell with this depressing atmosphere,” she announces, resolving to go out “and commit a creative act.”

—Jillian Steinhauer

Jillian Steinhauer writes about the politics of art and comics for publications like The New York Times, New York Magazine, The Nation, and The New Republic. She was a recipient of a 2019 Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers grant.