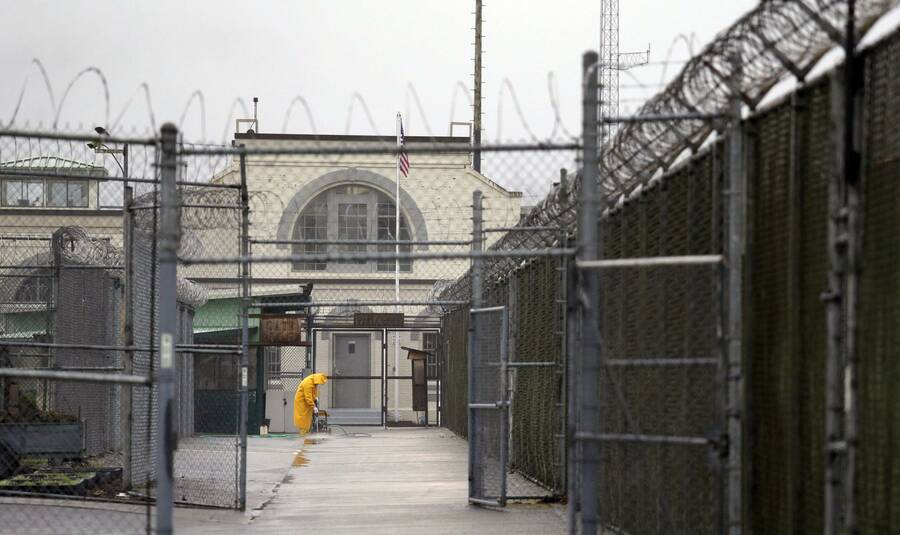

My Prison Is Still Flouting Public Health Guidelines

In a Washington State prison, masks are scarce, and guards don’t follow the rules.

MY MASK HANGS just below my nose, elastic worn and stretched out. Frequently, I pull it up, but it refuses to remain in place. I soldier on toward the dining hall with the rest of the prisoners. We’re herded in large clusters to our meal pickups in narrow corridors where social distancing is impossible. Once we get there, a guard at the entrance confronts me. “You need to have your mask on at all times, in a proper manner, no exceptions,” he says.

I don’t bother to argue or waste time trying to explain that the mask is worn out, has deteriorated beyond usefulness. I hold it above my nose until he is out of sight. I look over to see three guards sitting merely a foot or two apart from each other. Two have their masks resting on their chins, mouth and nose fully exposed while laughing and joking around. I wonder why the guard hasn’t reminded his co-workers to wear their masks properly. I’m annoyed as I continue toward the long line to receive my meal, bunched tightly against other prisoners.

Prisoners at the Washington State Reformatory (WSR) have been wearing the same cloth masks since September 1st. Since then, we have been offered nothing new. Prisoners have no ability to buy new masks, and when we ask the administration for masks, we are brushed off. Guards are furnished with new masks each time they enter the prison, whether they wear them or not. (On December 10th, after I discussed this article on a prison-monitored payphone and sent a draft of the piece using prison-monitored email, everyone on my unit was issued one disposable mask.) While the Washington Department of Corrections (WDOC) has urged prisoners to follow pandemic safety practices in memos, it has consistently failed to provide the necessary materials and conditions for us to follow those practices, and has allowed guards to flout the guidelines, even though they are a prime vector for passing the virus to prisoners.

Even prisoners deemed “high risk” by the WDOC’s own medical staff have been forgotten and left to fend for themselves. Tony Penwell, a prisoner at WSR, received a letter from the medical staff in March informing him he was on the list of prisoners considered to be “high risk” and that he would be receiving several masks a week. But since then, he has only received a couple of masks. When he contacted the medical staff to inquire about why he wasn’t receiving his weekly allotment of masks, he received no response.

“I’m scared,” he told me. “I have been told I’m high risk, that I should stay in my cell, wash my hands, and wear a mask, but where do I get a new mask? Mine is all worn and falling apart. I can’t stay in my cell all the time. I have to get food, shower, and call family.”

On November 25th, paper memos—similar to one issued in June—were once again posted around the prison mandating face coverings for all incarcerated individuals. The memo went on to say that “[s]everal messages have been shared with [the population] . . . regarding the importance of face coverings and their proper use.” It also reminded us what social distancing is and that we are responsible for maintaining six feet around us at all times, when “able to do so.” The problem is that we are pretty much never “able to do so.” When social distancing is deemed an inconvenience to staff—like when they are herding us to the dining hall or recreation areas—they never seem to worry about safety; they’re more interested in just getting us there as quickly as possible.

The missive failed to mention that prisoners haven’t been provided new masks in months; nor did it reveal why the WDOC’s own staff struggles to observe proper mask use and social distancing. In fact, the memo did not discuss staff at all—it only focused on prisoner behavior, though we have little ability to actually follow policy due to the DOC’s own actions. The memo included a threat to give prisoners infractions if they failed to comply with the rules of the mask mandate and the requirement to practice social distancing. Given that social distancing is nearly always impossible, anyone at any time could be in violation of these mandates and receive an infraction. This means they have set up a system which allows guards to target and punish whomever they choose.

(In a statement to Jewish Currents, a representative for the WDOC disputed many of these allegations, stating that prisoners can receive face coverings at any time from staff on their unit if they ask, that “facility management” regularly walks through facilities to encourage “both staff and incarcerated individuals to comply with Covid-19 protocols,” and that that when prisoners are transported between various settings, “facilities are staggering movements as much as needed, discouraging physical touching, and consistently encouraging individuals to continue maintaining physical distance whenever possible.”)

When prisoners have told the administration that guards refuse to wear masks, we’ve been instructed to write down dates and times that guards were observed not following rules, putting prisoners in a very dangerous position. If guards find out who reported them, they will no doubt retaliate. WSR has hundreds of cameras. If the administration truly cared about uncovering these infractions, they could watch the footage to see which staff members refuse to follow their directives, rather than put prisoners in a compromising position.

These contradictions leave many prisoners wondering if the memos are nothing more than an attempt for the WDOC to create a paper trail to protect itself as it continues to ineffectively run prisons during Covid-19. Stephen Sinclair, secretary of the WDOC, concluded the November memo with a line that prisoners have become accustomed to seeing on signs and memos around the prison throughout the pandemic: “Our top priority as an agency has been, and will continue to be, the safety of our incarcerated population, our staff, and our communities.” Many behind these walls, along with our loved ones, see this as a blatantly false statement. If anything, the WDOC’s actions show just the opposite.

If the WDOC really wants to keep prisoners safe, it should stop all transfers between prisons and county jails; punish staff who refuse to wear masks and social distance; stop doubling and tripling up prisoners in small cells; and regularly give prisoners much needed protective products including masks, soap, cleaning supplies, and alcohol-based hand sanitizer. Until this is accomplished, everything department representatives say about pandemic safety is nothing more than talk.

Christopher Blackwell is serving a 45-year prison sentence in Washington state. He is a contributing writer at Jewish Currents and contributing editor at The Appeal and works closely with Empowerment Avenue. He co-founded the organization Look2Justice.