Matrilineage

In “Matrilineage,” Susannah Sharpless makes clear that inheritance is not linear. Trauma propels anxiety unevenly across generation and circumstance. This is manifest in the line breaks, where meaning shifts sharply, an expression of both precarity and possibility. “I learned that not only birth could name,” Sharpless writes. Her forked statement registers harm’s indelible marks, even as it testifies to the ways that destruction and creation can share a root.

– Claire Schwartz

Matrilineage

I was in New York that week, in a lobby,

waiting to speak to someone

about one day being paid for what I was willing to do for free.

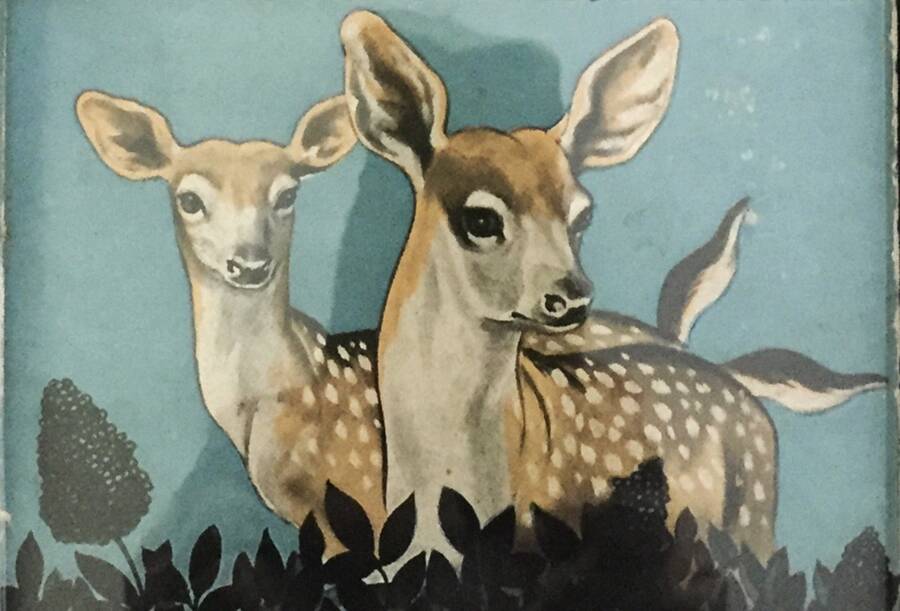

Behind the front desk was a book about Bambi’s Jewish roots.

I knew just from the font that meant the Holocaust,

the letters red against a black background.

Later, mid-sentence, in the middle of the interview,

something gray began worrying my left eye:

panic, that birthright.

I had thought I was full up with fear

but I guess I will always have to make room for the ancestral

or it will make itself a room in me,

like my grandmother insisting that I was hungry

when she saw me, pulling from the freezer

tubs of chicken soup choked with spikes of golden ice.

If my grandmother had seen me in that room

she would have thought I was so skinny,

would have thrown up her hands in despair.

But I was too anxious to eat back then,

and it was only because I was too anxious to eat

that I could wear the skirt I did while listening to a man tell me he would think of me

if an opening ever appeared. The room we were in was so small

and there was a window but I couldn’t see it from where I was sitting,

there was light somewhere but I couldn’t see it from where I was sitting,

somewhere the wind was blowing fresh and the ceilings were high

and the walls soared up so tall that to sit beneath them seemed an act of grace,

and though I couldn’t see it, from where I was sitting,

New York was hurtling its gray wealth against the light.

Afterwards I googled the book and learned

the author says what makes Bambi essentially Jewish

is persecution at the hands of strangers.

I thought then of the time a friend’s father

offered us the meat of a deer he’d killed and called venison

and I learned not only birth could name.

I’ve never seen Bambi but I know hunters shoot the mother

and I can feel the spasm of the dark wood,

the watchful yellow eyes of the spared.

I once expressed an adolescent spiritual indecision

between the faith of my mother and the faith of my father

and my grandfather said, “The Nazis didn’t let your cousins choose.”

When I finally moved from Indiana to New York,

I wasn’t half-and-half anymore: the devout told me

I was Jewish, everyone else heard

I was nothing. They all knew too much

about inheritance.

Susannah Sharpless is a writer from Indianapolis, Indiana.