Introduction: The Soviet Jewry Movement, Revisited

At its root, the struggle over the fate of Soviet Jews was a struggle over where in the world Jews belonged.

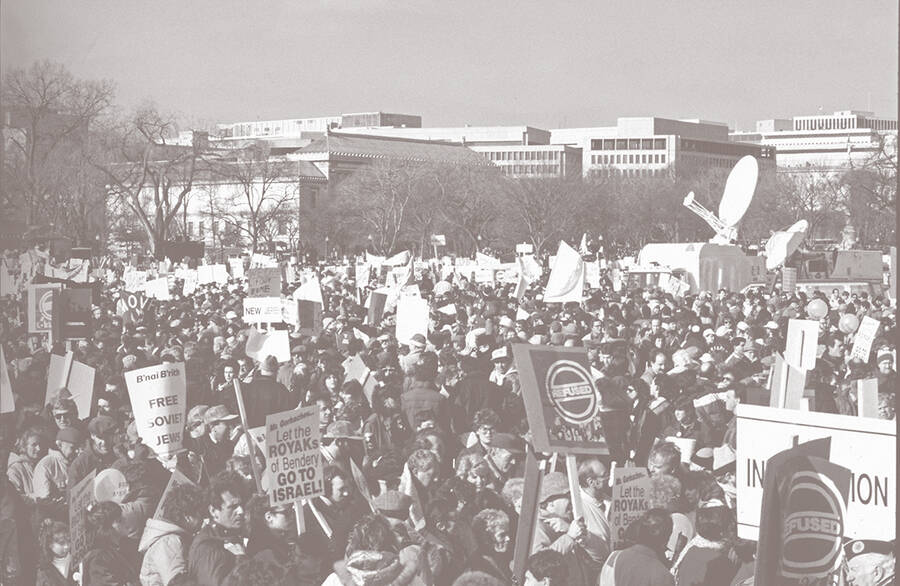

The largest Jewish political rally in United States history took place on a mild winter day, December 6th, 1987, when a quarter of a million people gathered on the Washington Mall for an event advertised as a “Freedom Sunday for Soviet Jews.” People of all ages arrived from cities across the US holding signs bearing the faces of “prisoners of Zion” and wearing pins with slogans like “Let Freedom Ring for Soviet Jews.” On the main stage stood a giant menorah and a large banner with the words “Let Our People Go” scrawled over red brick, invoking the biblical slavery in Egypt. Between speeches, the crowd sang inspirational songs, from the civil rights gospel tune “We Shall Overcome” to the movement’s Hebrew anthem “Am Yisrael Chai,” accompanied by guitar and tambourine.

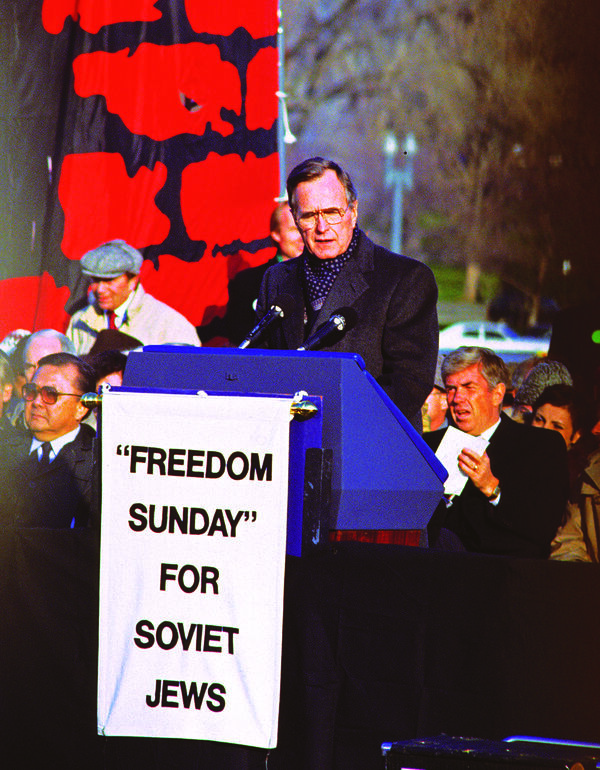

Kicking off a program of speakers that included Vice President George H.W. Bush as well as several members of congress, Morris Abrams—the chairman of the National Conference for Soviet Jewry (NCSJ), which had helped organize the event—reminded the crowd of the movement’s broad aims. “We are here to insist that [the Soviet government] comply with the human rights promises [it] made in Helsinki!” he declared, inviting cheers from the crowd, which waved American and Israeli flags overhead. “We are here to affirm our ties to Soviet Jews, cut off from their brethren, persecuted, and denied the right to practice their religion!” The memory of the Jewish genocide in Europe haunted the speakers’ appeals. When Nobel laureate and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel spoke, he addressed the rally’s subtext directly: “It is now clear that had there been such a demonstration of Jewish and human solidarity and concern in 1942, 1943, and 1944, millions of Jews would have been saved,” he said. “But too many of us were silent then. We are not silent today.”

The 1987 rally occurred at the peak of what has come to be known as the “Soviet Jewry movement,” or the “Save Soviet Jewry movement,” an international effort that brought together the world’s three largest Jewish populations—in Israel, the US, and the Soviet Union—during the years of the Cold War. From the 1960s until the collapse of the USSR in 1991, Jewish activists in the US and the new State of Israel lobbied for the right of Jews to leave the Soviet Union. Academics debate when the organizing began and whether it constituted a single, unified movement or many discrete ones. What is clear is that the effort gained the most momentum in the US, where a wide range of establishment organizations, militant Jewish student groups, and religious leaders devoted themselves to the cause, sometimes clashing in their aims and tactics. In its heyday, the movement’s rallies and protests attracted extensive media attention and touched virtually every aspect of American Jewish life.

Vice President George H.W. Bush speaks at the “Campaign to the Summit” rally for Soviet Jewry in Washington, DC, on December 6th, 1987.

Today, the movement is remembered in the popular imagination, by liberals and conservatives alike, as a unique moment when Jews across the world came together for human rights: “the last event that united practically all Jews, independent of their political interests and religious views,” in the words of Nati Cantorovich, an official involved in Nativ, the Israeli agency dedicated to Soviet Jews. Contemporary journalists and academics defer to activists’ characterization of their decades-long campaign as the “Jewish civil rights movement.” In a blurb for New York Times editor Gal Beckerman’s sweeping 2010 account, When They Come For Us, We’ll Be Gone: The Epic Struggle to Save Soviet Jewry, author Cynthia Ozick placed the movement “[a]mong the great liberation strivings of the twentieth century,” comparing it to struggles against apartheid in South Africa and British colonialism in India.

Central to this narrative is the idea that American and Israeli activists didn’t only rescue Soviet Jews, but also saved themselves along the way. Beckerman’s book in particular canonized this version of history, arguing that in the decades before the movement, American Jews were nearing spiritual extinction. In his view, the “tribal instinct to rescue their own” allowed American Jews to “stand tall as a community,” and heal from the “psychic scars” left by their ineffectuality during Holocaust. Like others who have explored this history, he traces the origins of the struggle for Soviet Jews to the resurgence of Jewish identity in the 1960s, when the civil rights movement, guilt over American complacency about the Holocaust, and Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War awakened Jewish national feelings across the globe. Beckerman approvingly writes that by the movement’s end in 1991, American Jews had learned how to organize effectively for Jewish interests, adopting a particularist approach that persists to this day—and which Beckerman credits for giving rise to the powerful Israel lobby.

This triumphant account convincingly shows how the movement helped to construct an American Jewish identity politics, but it takes for granted the activists’ own claim that they performed a mass rescue of passive Soviet Jewish victims, failing to interrogate the political contexts that gave rise to that narrative, or the political ends it has continued to serve. For decades, many in Jewish institutional leadership have made use of the movement as a vehicle for a Cold War rhetoric of American exceptionalism. Reflecting in a 2021 interview on his tenure as the CEO of the American Jewish Committee, David Harris, a self-proclaimed “foot soldier” in the Soviet Jewry fight, described his career as one of a “proud American, blessed to have been born in a land of freedom and opportunity,” who was “devoted to defending democracy and freedom against the ever present threats of totalitarianism on the left and fascism on the right.” Meanwhile, the false equivalency drawn by many student activists at the movement’s height between Nazi fascism and Soviet socialism still abounds today, fueling criticisms of the American left. The experiences of Soviet Jews were often invoked amid Bernie Sanders’s presidential campaigns to argue that socialism is not only “a conspiracy of losers against achievers,” as one Russian Jewish interviewee told The Atlantic, but also “fertile soil for hatred of Jews,” as Forward columnist Ari Hoffman wrote in early 2020. From Israel, author and former Jewish Defense League member Yossi Klein HaLevi compared British Jewry’s opposition to former British Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn and “the Jew-hatred emanating from the left” to the Soviet Jewry movement’s fight against Soviet socialism, arguing that, “by denouncing the Soviet Union as the ideological successor of Nazi Germany, the Soviet Jewry movement defined the enemy and left no room for equivocation.”

The popular story also foregrounds a Zionist worldview, framing Israel as the primary savior of Soviet Jews. Movement participants like Israeli politician Natan Sharansky, who rose to prominence as a Soviet dissident, speak of the flow of Jews out of the Soviet Union as a modern-day exodus tale. In his 2020 memoir, Never Alone, Sharansky connects the refuseniks—Soviet Jews who sought to emigrate to Israel but were refused exit visas—to “the chain of Jewish freedom fighters,” from “the exodus from Egypt, to the Maccabees in ancient Judea, to the founders of Zionism and the pioneers of modern Israel.” In a related vein, the researcher Izabella Tabarovsky has sought to undermine criticisms of Israel by equating Soviet antisemitism and contemporary anti-Zionism. The unique experiences of Russian-speaking Jews, she argues in Tablet, make them canaries in the coal mine, since the “experience[s] of antisemitism also gave Soviet Jews insights into the kind of left-wing antisemitism that comes under the rubric of ‘anti-Zionism.’”

While many American and Israeli Jews believed themselves altruistic saviors of their Soviet counterparts, they were also political actors whose activism advanced their own countries’ domestic political agendas.

This special section revisits the global Soviet Jewry movement by turning to the three domestic contexts where it was largest: the US, Israel, and the Soviet Union. Bringing together historians, researchers, and journalists, it challenges the usual narratives, raising questions about the unity of Jewish opinion on the subject of Soviet emigration and the accuracy of viewing the movement as primarily a struggle for human rights. This section reexamines the history in the context of Israeli and American national interests, painting a picture of Israeli activism motivated less by a commitment to human rights than by the country’s own demographic anxieties, and of a US movement driven not only by an attachment to Jewish identity, but also by an alliance with an emerging cohort of influential neoconservatives. Pushing back on the popular narrative’s tales of “rescue”—which tell us little about the complex manifestations of antisemitism in the late 20th century Soviet Union—the pieces about the USSR offer a more nuanced look at a Soviet Jewish population that was far from united in the desire to leave. As a whole, this section challenges the assumption that Jews inherently share interests across international borders. While many American and Israeli Jews believed themselves altruistic saviors of their Soviet counterparts, they were also political actors whose activism advanced their own countries’ domestic political agendas.

In the US, American Jewish activism on the Soviet Jewish cause reflected rightward political currents. Hadas Binyamini revisits the US movement’s major legislative victory, the Jackson-Vanik Amendment to the 1974 Trade Act, which conditioned trade between the US and the Soviet Union on the latter easing restrictions on Jewish emigration. While some scholars have heralded the amendment as the outcome of successful identity-based organizing, Binyamini shows that it owed at least as much to a rising neoconservative faction in the Democratic Party, which entered a long term alliance with Jewish institutions when both threw their weight behind Jackson-Vanik. Meanwhile, American Jewish leftists who had been Communists or fellow travelers kept their distance from the movement, struggling to grasp developments in the Soviet Jewish situation without joining the chorus of Cold Warriors—a predicament Jewish Currents’ editor emeritus Lawrence Bush explores in a look at the magazine’s own archives. In Israel, as Jonathan Dekel-Chen shows, a different set of national interests drove the movement. The country’s leaders were wary of stepping into the Cold War standoff between the US and the USSR, but keen to expand their Jewish population by absorbing Soviet émigrés. Their insistence that Jews leaving the Soviet Union come to Israel, even when the émigrés themselves wished to go elsewhere, created significant tensions with Jewish activists in the US—a situation very different from the established Israeli narrative in which Israel led the Soviet Jewry movement

around the world.

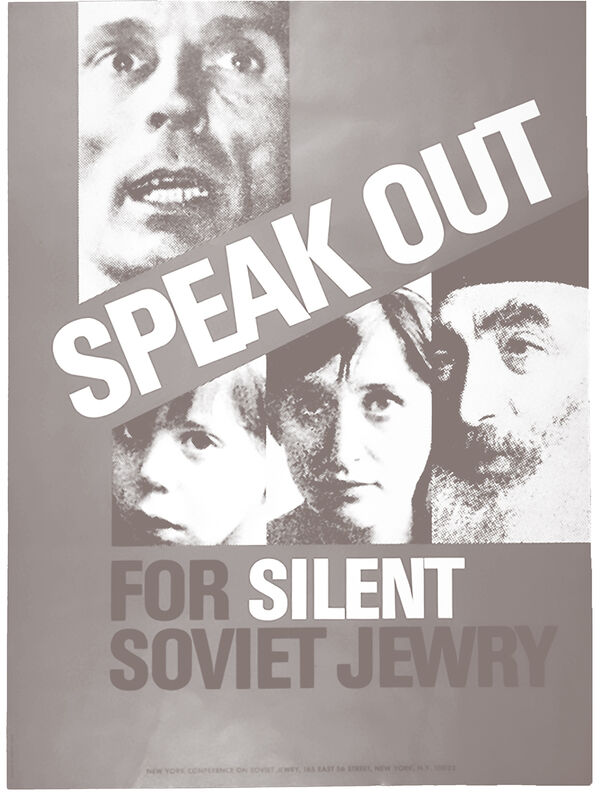

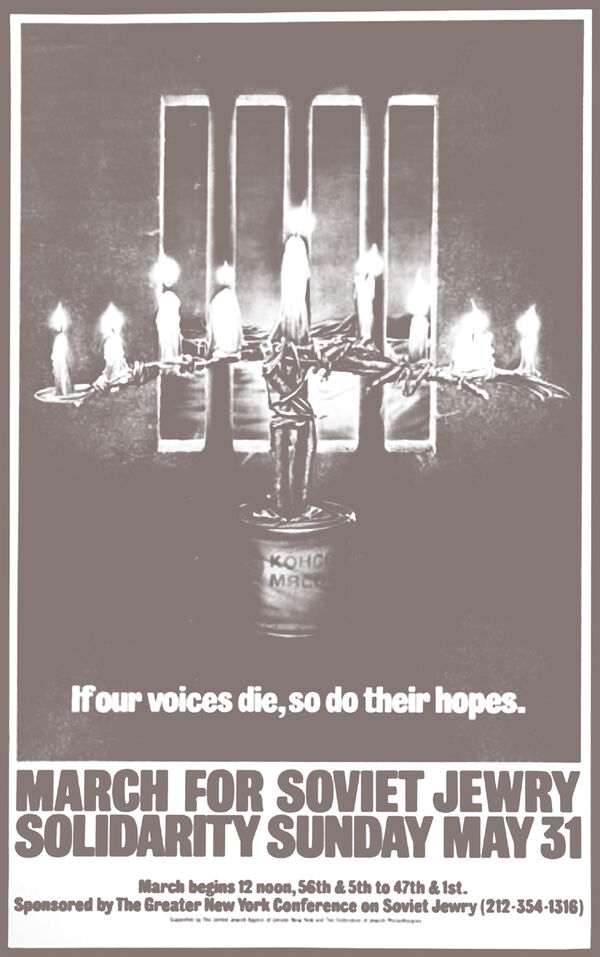

Protest posters from the Soviet

Jewry movement

Meanwhile, in the Soviet Union, Jews’ perspectives on their quality of life and their level of interest in emigration were complex and varied, a far cry from the monolithic desperation to leave posited by the global movement that advocated on their behalf. The refuseniks, who sought emigration to Israel, most often on ideological grounds, served as useful poster children for the Soviet Jewry movement, but they only numbered a few thousand in a Jewish population of over a million. In her piece revisiting the history of Soviet antisemitism, Anna Shternshis argues that though anti-Jewish sentiment remained common after its peak under Stalin, it did not necessarily dominate the way in which most Soviet Jews thought about their lives in the USSR; even many who sought to emigrate did not cite antisemitism as a motivating factor in their desire to leave. Other groups of Soviet Jews, as Emily Tamkin writes, did not wish to emigrate at all, including some who joined a legal dissident movement that fought to reform the Soviet Union from within. Still others, as Olesya Shayduk-Immerman discovered in extensive interviews with Soviet Jews, were transformed by a fledgling, informal movement of Jewish study, enabled in part by Soviet social provisions—a pattern of experience that complicates simplistic narratives about the impossibility of Jewish life inside the Soviet Union.

Taken together, these pieces suggest that we can read the Soviet Jewry movement as a debate about where Jews belonged, and which of the world’s three Jewish population centers—the US, Israel, or the USSR—presented them with the best home. This question has roots in an earlier chapter in Russian Jewish history: In the years leading up to the 1917 Russian Revolution, at the turn of the 20th century, most of the country’s Jewish population—then the largest in the world—was confined to the Western borderlands of a declining empire, facing a series of upheavals that began with a wave of anti-Jewish pogroms in 1881, and continued as Jews’ economic prospects in the Pale of Settlement dwindled. Historians argue that these crises gave birth to modern Jewish politics, as Jews faced the question of whether to stay in Russia, emigrate to America, or join the Zionist movement and resettle in Palestine. Global Jewish organizations were formed to help Russian Jews deal with these crises, such as the Jewish Colonization Association, founded in 1891, and the American Jewish Committee, established in 1906. But after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and tightened immigration restrictions in the US, the vast majority of Jews stayed in Russia and acclimated to their new political circumstances. In the 1920s, American Jewish organizations pivoted their fundraising to the cause of building Jewish life in Eastern Europe—the Soviet Union and Poland—rather than focus on emigration to the US or colonization in Palestine.

By the mid-20th century, however, the question of Jewish belonging seemed more urgent than ever. The purges of the Great Terror, the Holocaust, Stalin’s anti-Jewish campaigns, and persistent anti-Jewish sentiment thereafter had dramatically unsettled the idea that Jewish life would be stable in the USSR. By then, decades of mass migration, revolution, war, and genocide had redistributed the Jewish population into three global centers, each of which promised a very different kind of existence. With Russia’s Jews once again at a crossroads, their would-be rescuers’ visions of the Jewish future stemmed from differing interpretations of Jewish history. Those who perceived it as an unending litany of persecutions argued that Jews could only be safe in the Jewish national homeland in Israel. But many Jews in the US, buoyed by their own economic success, implicitly argued that the future of Soviet Jewry lay in American democracy and free market capitalism. Soviet Jews, for their part, were torn about whether to stay in a country where many enjoyed relative economic comfort even as they faced anti-Jewish discrimination, or whether to risk trading the familiar for the unknown.

One hundred years after the birth of modern Jewish politics in Russia, Jews looked at the three paths represented by Israel, the Soviet Union, and the US and seemed to ask: Who made the right choice?

Our retelling offers a different story of Jewish belonging. One hundred years after the birth of modern Jewish politics in Russia, Jews looked at the three paths represented by Israel, the Soviet Union, and the US and seemed to ask: Who made the right choice? American and Israeli Jews have long assumed that the answer was obvious; the collapse of the Soviet Union struck many as a form of confirmation. But as the pieces in this section argue, any story told through the lens of its outcomes has blind spots. An honest recounting of the long history of Jews in the Soviet Union reminds us that, until recently, their investment in American and Israeli projects was much more ambivalent than it is today.

Tova Benjamin is a PhD candidate at New York University, studying Russian and Jewish history. She was born in Chicago and lives in Brooklyn.