Hide and Seek

Adam Liam Rose’s recent works on paper investigate the violence and vulnerability of structures built for “safety.”

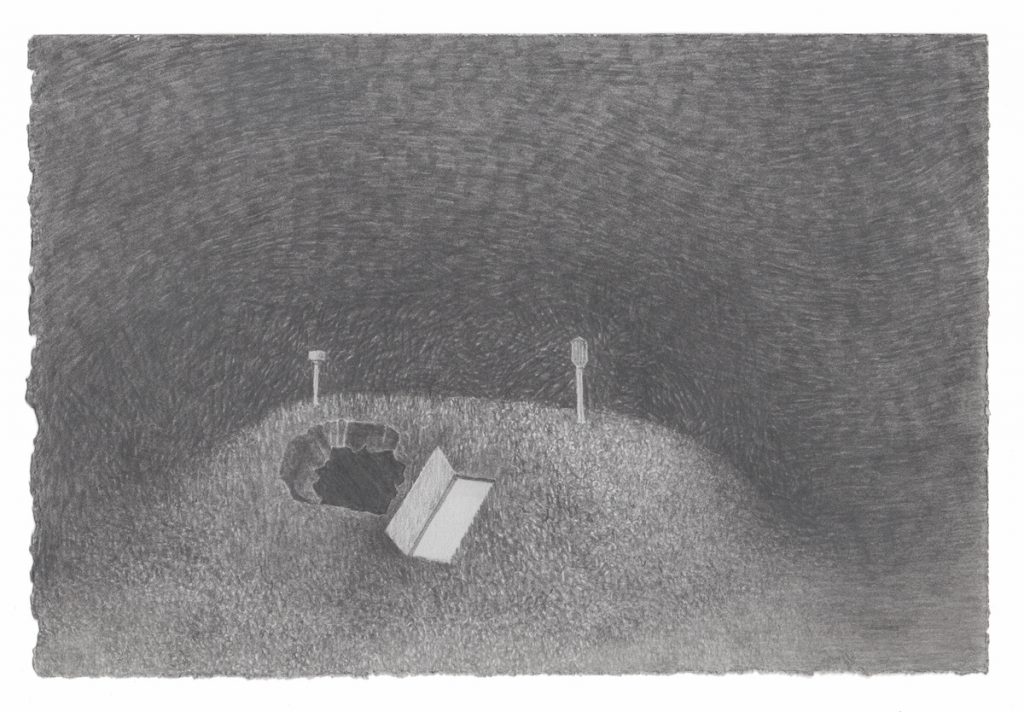

ON THE SLOPE OF A GRASSY HILL, an illuminated trapdoor sits ominously propped open. Beside the bright white doorway, a cutout reveals the built layers of this curious bunker. The hideout, punctured, begins to betray its inner infrastructure. The soft, organic exterior still suggests the secrecy of camouflage, but the streetlamps—uncannily out of place on the hilltop—not so discreetly mark the spot. The interplay of stealth and exposure invites us to ask: Whom do these structures protect, and whom do they exclude?

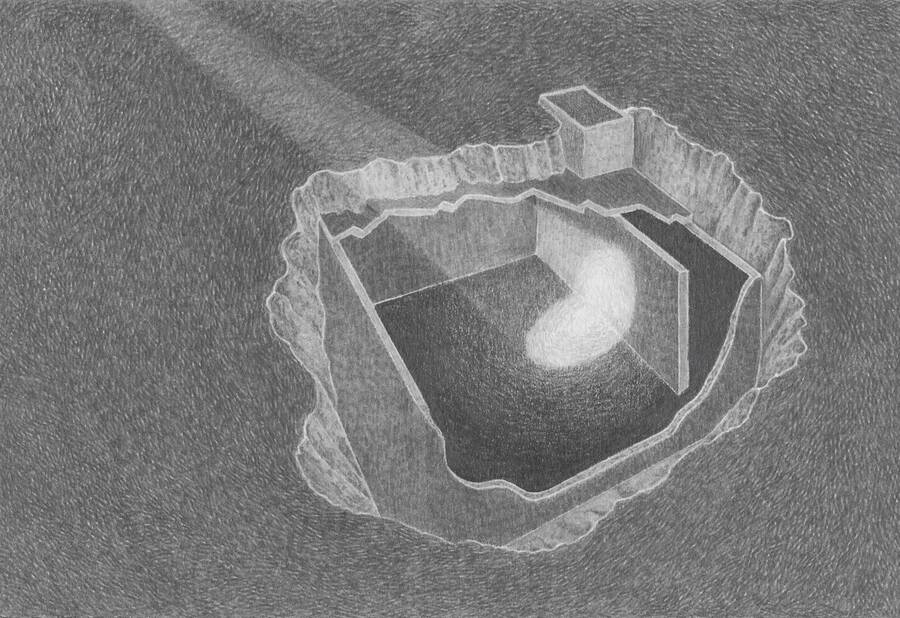

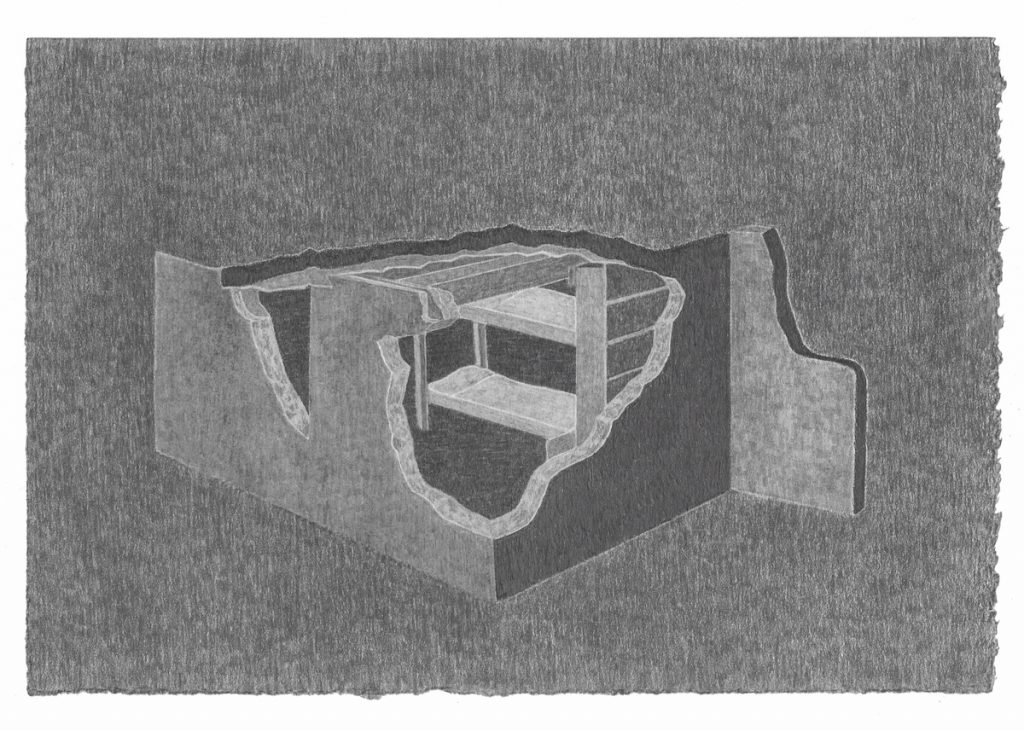

This chilling image, Stages of Fallout (portal) is part of “Stages of Fallout” (2019–present), an ongoing series of graphite drawings by Israeli American artist Adam Liam Rose. To date, the series comprises more than 40 pieces. Many, like (portal), depict fallout shelters—some based on illustrations from The Family Fallout Shelter, a booklet published by the United States Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization in 1959, at the height of the Cold War, which includes instructions for building five “basic fallout shelters.” (“One of the five,” the manual notes, “has been designed specifically as a do-it-yourself project.”) From these anodyne schematics, or pure invention, Rose produces playful grayscale images that render these wartime structures with a hand-drawn texture that recalls the graininess of an Etch A Sketch toy. In a handful of the drawings, Rose includes a spotlight shining down from above, as if to accentuate how these bunkers’ hollow cavities, like the nationalism that undergirds them, demand scrutiny. Read with the series’s title in mind, these overhead lights also suggest a stage for the theatrics of colonialism and occupation, illuminated by unrelenting surveillance beams.

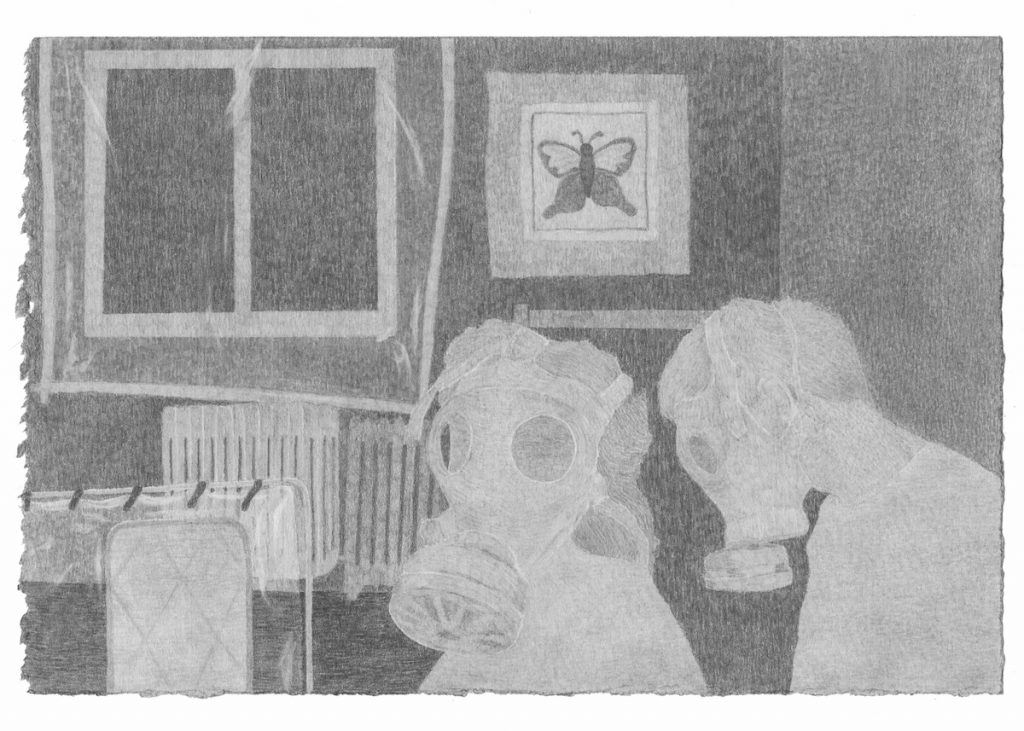

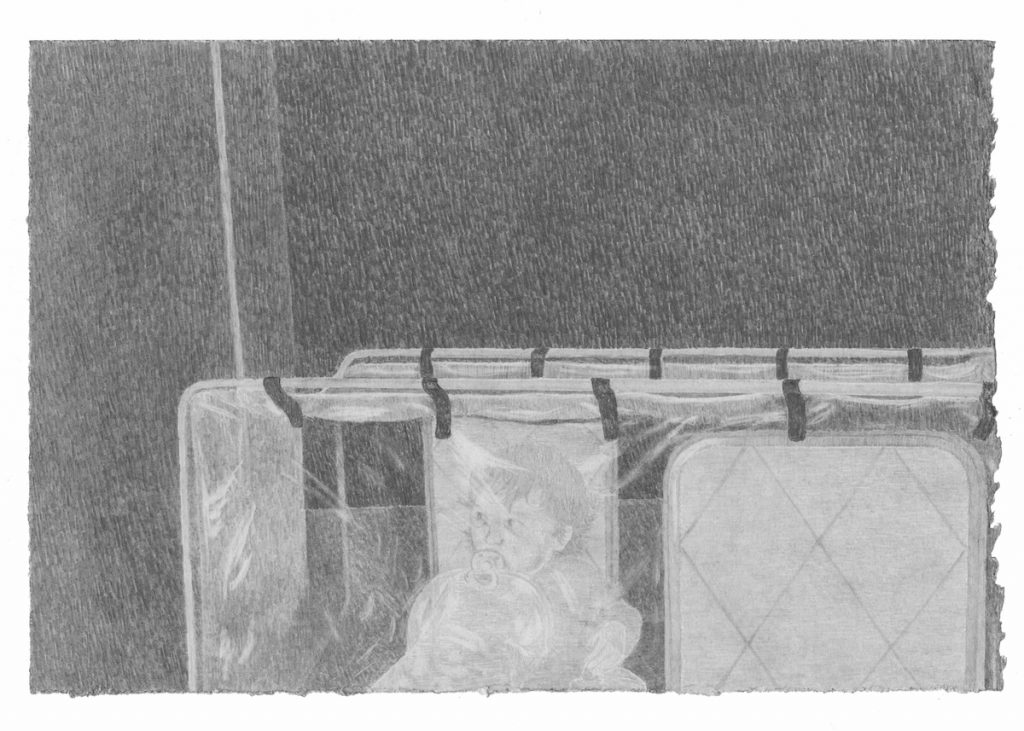

Absent from Rose’s floating shelters, though, is the mythic entity they exist to protect: the family. Rose’s own parents appear elsewhere in the series, in desaturated drawings based on family photos, to which Rose applies a similar style. In Stages of Fallout (mother & father with butterfly), the living room from Rose’s childhood home—in the Pisgat Ze’ev settlement of East Jerusalem—is transformed into a bunker; Rose’s parents are adorned in gas masks. Stages of Fallout (plastic protection), based on another photo, gives us an alternate view of this living room, in which Rose themself appears as an infant, quarantined in a plastic-encased crib. These transformed snapshots, which document the first Gulf War (1990–91) and foreground an Israeli family’s government allotment of protective military gear, ask how state hyper-militarization reverberates even in intimate spaces.

By putting scenes from Gulf War–era Israel in conversation with illustrations of Cold War–era American structures—in each case, depicting architectures and technologies deployed to protect those the state believes in protecting—Rose points to the relationship between the two militarized settler-colonial projects. Rose has an intimate familiarity with both nations. Born in East Jerusalem in 1990, they lived there until 2002, when they moved to the US. They’ve gone back to Israel annually to visit family. It was on one 2012 trip to attend their grandfather’s funeral that they began to pursue the line of inquiry that led them to “Stages of Fallout”; their grandfather’s passing had prompted a reckoning with their family’s history, and their implication in larger political narratives. On this trip, they started uncovering archives of family snapshots, and also taking new research photos. During a Zoom studio visit in May, Rose shared their screen to show me pictures, taken on this trip, of the view from their childhood backyard into the Shuafat refugee camp in Palestine; they told me they’d shyly knocked on their old apartment door to ask the current occupants if they could revisit the view.

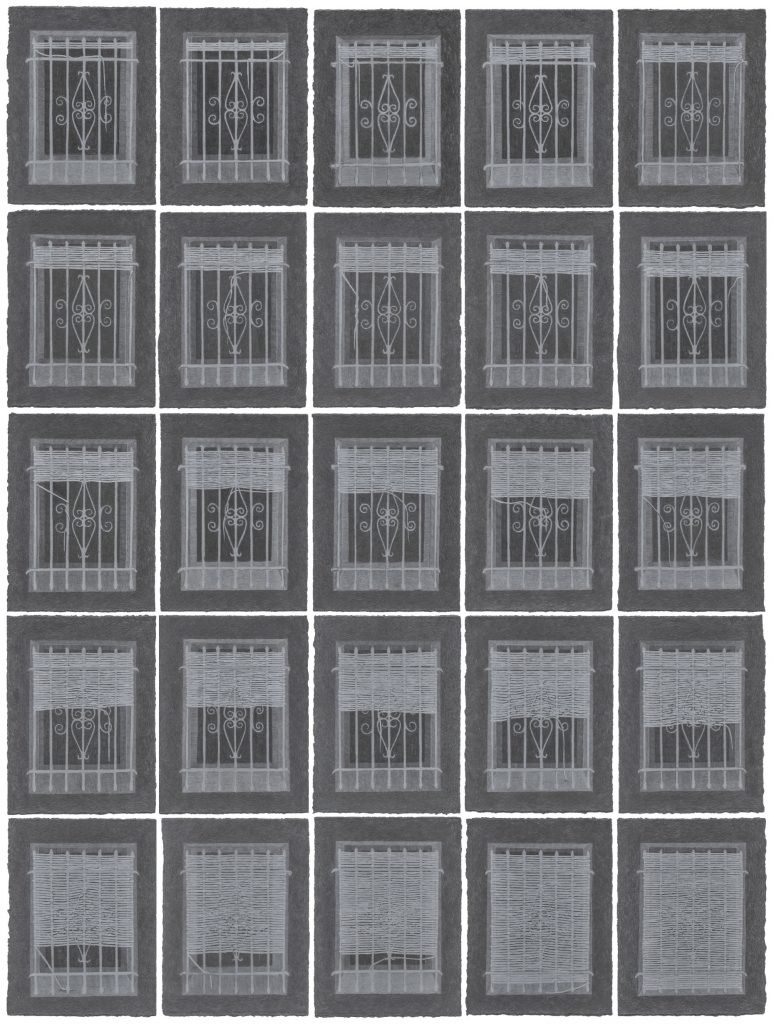

Rose continues their inquiry into the relationship between structures, safety, and exclusion in another recent series of graphite drawings also rooted in their childhood home, “Soragim (Between the Bars)” (2020). The project comprises a series of 30 illustrations of the same barred apartment window, progressively covered in yarn.The drawings are based on a 2013 installation and performance in which Rose wove yarn around a life-size, fabricated windowsill—an approximate reproduction of one from their childhood apartment. In a statement about this project, Rose explains why the window and its bars loom large for them:

As a young flamboyant child with two military-bound brothers, I was sometimes picked on as the younger and weaker in the herd. On one occasion, my brothers locked me between the window and bars of our home. While the act was short-lived, and I can hardly remember it myself, it has been a family story that [pops] up around the dinner table and at holiday gatherings. As an adult, I’ve considered this space in symbolic terms as a “queer” space; one that exists outside of, between the margins, and out of sorts.

In the new series, Rose revisits this scene and the earlier installation, reimagining it in two dimensions, as if scrapbooking a reference point in their life and work. Rendered in unassuming, accumulative flecks of pencil, much like in “Stages of Fallout,” the grays of these small-scale drawings set a somber tone. In an artist statement for the series, Rose notes that the title takes on the multiple contradictory meanings of the Hebrew word “soragim,” which can signify bars or a knitted structure. Rose tenderly softens the bars’ harshness as a way of processing the fraught experience of growing up queer in Israel’s heterosexist culture—a culture defined by the maintenance of boundaries. In their statement about the 2013 installation, Rose reflects that their interpretation of the window space as queer “made sense to [them] both as a queer person, and also as someone who grew up to question [their] ‘homeland.’”

In each of these two recent series, the drawings’ modest size—slightly smaller than sheets of generic printer paper—stands in contrast with Rose’s earlier work, which took the form of large-scale installation and performances (sometimes recorded on video). But much of the subject matter is continuous; previously, too, Rose explored questions of safety and structural violence. Paradise of Greenery (2016), for instance, riffs on a mural that decorates a segment of the Israeli side of the separation barrier with the West Bank with a tranquil pastoral scene—an image Rose suspects was commissioned by a government contractor. Rose’s moveable plywood recreation of this mural and the segment of the separation wall on which it’s painted features a lone aqueduct, a green hill, and blue sky. Rose’s reproduction disrupts the cartoonish abstraction of harm that the decoration attempts to communicate.

The drawings of “Stages of Fallout” and “Soragim (Between the Bars)” have been debuting on Rose’s Instagram feed, the bright colors of the effusive emoji responses disrupting the work’s own meditative tone. They’re full of melancholy and also resistant to nostalgia, in a mournful disavowal of both Israel and the US. Scrolling through the images, I wonder what catharsis comes from the devotional act of hand-drawn replication at play in both series. The slow, even calming process of repetition itself seems to evoke the tranquility promised by the armor of bunkers and window bars, while also subtly undermining the violence upon which these structures are premised. How, the work seems to ask, can such spaces be subverted to become true havens of meditation, which press against the nationalist logics of exclusion that define them? Rose’s graphite pencil softens its sharp tip against the page, again and again, modeling a continuous reflection on the ever-replicating forms of violence into which we’re variously born.

Ariel Goldberg’s publications include The Estrangement Principle (Nightboat Books, 2016) and The Photographer (Roof Books, 2015). They are a 2020 Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant recipient for their book in progress Just Captions: Ethics of Trans and Queer Image Cultures.