For the Sake of Truth

Poet and activist Mohammed El-Kurd discusses his debut collection, the vexed meanings of visibility, and the long history of Palestinian freedom struggles.

In October 2020, the Israeli magistrate court of Jerusalem, a fixture of its apartheid legal system, ruled that half of the Palestinian families in the East Jerusalem neighborhood of Sheikh Jarrah would be dispossessed of their homes. Among them was the family of writer and activist Mohammed El-Kurd. When the ruling came down, Mohammed, who is now 23 years old, joined with his twin sister Muna and other community members to mount the #SaveSheikhJarrah campaign, which broadcast the conditions of Palestinian life under occupation and galvanized support for resistance against settler land theft. The movement ignited a flame. As protests flourished on both sides of the Green Line and across the globe, Israeli violence escalated, culminating with the bombing of Gaza in the spring of 2021. This tremendous horror laid bare the entrenched logics of the occupation, and El-Kurd gained international recognition, regularly making media appearances to translate the situation on the ground for audiences around the world.

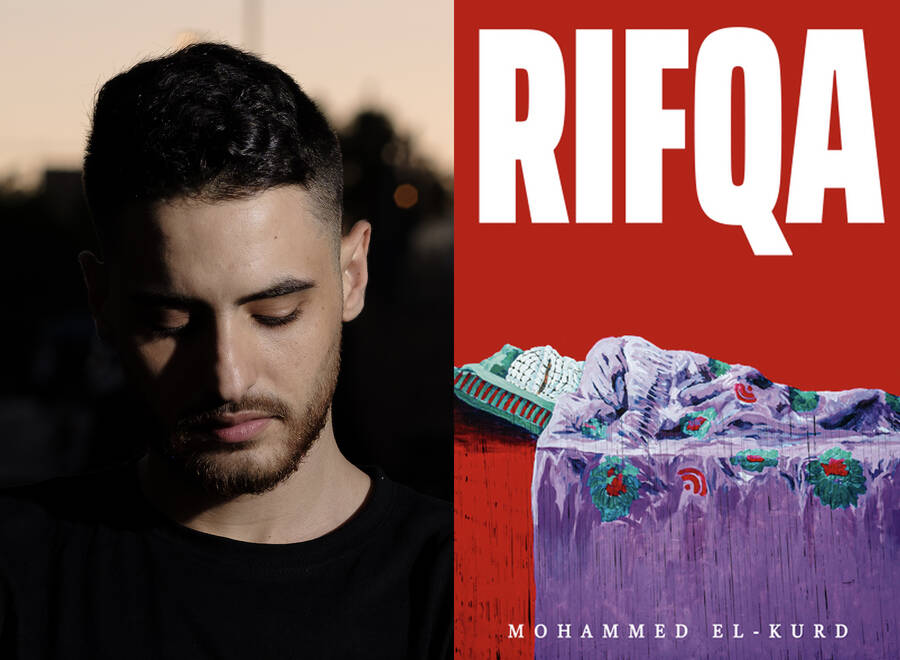

For his critical role in mobilizing global solidarity with Palestine, El-Kurd was named, alongside his sister, as one of Time’s 100 most influential people of 2021, and he recently became The Nation’s inaugural Palestine correspondent. But long before the confluence of spectacular violence, freedom struggles, and his own writing practice catapulted him into a particularly bright spotlight, El-Kurd, who is currently an MFA candidate at Brooklyn College, was honing his craft as a poet. His debut collection, Rifqa—named for his grandmother, whom Israel made a refugee in 1948 when she was forced to flee her home in Haifa, and who fought for Palestinian liberation until her death in June 2020 at 103—was published by Haymarket Books last week. As he told me: “I feel like had I known there was going to be this much of an audience for this book, I would have had an urge to self-censor. I didn’t do that. All my truth is in here.”

El-Kurd’s poems are attuned to language as a terrain of struggle. Refusing the myriad euphemisms that conceal and authorize Israel’s ongoing violence, he insists on a clarity that emplots each act in a field of history. “It’s the same killing / everywhere. / Seventy-two years later / we haven’t lived a day,” he writes in a poem entitled “1998/1948.” But if El-Kurd’s poems witness the relentless reiterations of settler colonial violence, they also document the rebuttals and tendernesses—Mahfoutha Ishtayyeh chaining herself to a tree, “olive skin on olive skin,” in the face of an Israeli bulldozer; Rifqa El-Kurd welcoming her grandson home from school each day with jasmine wrapped in Kleenex—seeds of other futures nestled within the present.

I spoke with El-Kurd about the vexed meanings of visibility, the coercions of English, and the long history of Palestinian freedom struggles.

Claire Schwartz: How are you feeling, given your visibility at the moment?

Mohammed El-Kurd: It’s complicated. People have worked for many years for Palestinians to have access to large public platforms, and the Time 100 is a positive indication of the way that Palestine has become central to global discourse. But the creation of icons—which reduces the struggle of an entire people to one or two faces—is not the most helpful thing to our cause. And for the individual, this degree of visibility robs you of your privacy.

But I am very excited about the position at The Nation, because more than visibility, I would like to see structural change in the media, and I hope this will inspire more outlets in the United States to start their own Palestine departments.

CS: You’ve been negotiating visibility for a long time. In a piece first published last year and reprinted at the end of Rifqa, you write: “Because the Israelis moved into half of the house, separated from my family only by drywall, our home’s 2009 confiscation was highly publicized. The house became an international hub to which solidarity activists and curious liberals alike made pilgrimages.” What was it like to grow up in that kind of spotlight? How has that experience informed your relationship to the possibilities and limits of representation?

MK: The fact that our home became an international hub offered me ten years of training in talking to the media. But why—as an 11-, 12-, 13-year-old—was I put on a podium? There’s something incredibly nefarious about how children are positioned in those situations.

Just yesterday I received this note from someone who lobbies on the Hill: “Five senators’ offices have scheduled the week ahead to meet a Palestinian child, who will present their dream of what peace means. Would a Sheikh Jarrah child like to be the guest speaker along with their parent or relative to translate?” I thought that was the most outrageous request. Because American policymakers are too racist to meet with adults who can form coherent analyses and make actual demands, they fly in children—who are heavily influenced by the people around them—put them under the spotlight, and call that representation. That is exploitation.

CS: In your poetry, you write about divergent meanings of age, of time, as a form of imperial violence. In the poem “Boy Sells Gum at Qalandiyah,” you write: “The boy is eight, which is twenty-two for Americans.”

MK: I hope I said “white America”! Childhood is robbed from Palestinian children growing up under military occupation in many different ways. There’s no point in me showing you a picture of a child and saying, “Look. He’s just a child.” Anyone who is able to see the picture can see that this is a child. Why are we talking about that? The way you restore that stolen childhood is not by pointing out that these are children. That’s just a way of misdirecting the conversation so the occupation can continue unchecked. We should be asking about the machine that continues to rob children of their childhoods. If the Israeli colonial system is not dismantled, then there will always be children without childhoods.

CS: In an interview with the Israeli poet Helit Yeshurun, the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish, who was six in 1948, said in Adam Yale Stern’s translation: “Childhood was taken from me at the same time as my home . . . The question is whether it’s possible to restore the childhood that was taken by restoring the land that was taken, and that’s a poetic quest that gives rhythm to the poem itself.” This idea that the poem’s music—its ongoing present—arises from the enmeshment of past and future made me think of your line from “The Biggest Punchline of All Time”: “I assign imagination to memory.” How do you think about the relationship between memory and imagination, or history and futurity?

MK: So much of our collective memory as the Palestinian people has centered around victimhood. We have in fact been victims since British colonization and even before then; that victimhood is not internationally recognized and we have not been offered reparations, so there is an urgent need to assert that we are victims in a context of an extreme power imbalance. But what gets lost in that story is the years and years of Palestinian political agency and resistance. Growing up immersed in this collective history of victimhood, you grow up unaware of your capacity. That’s why I think it’s important to study our history in a way that also reminds us of our ability to imagine, and of the ways in which we were able to say no, to fight back.

Last month, six Palestinian prisoners broke free from an Israeli prison referred to as “the safe” because of how tight security is there. This is a system that I have thought of for many, many years as impenetrable. To hear about these six men digging a tunnel with primitive tools and breaking through to their freedom—and reveling in that freedom for more than a week—was a reminder of why it’s critical, even as we acknowledge the power disparity of Israeli settler colonialism, to remember that nothing is infallible.

CS: In Rifqa, you invoke a broad geography of freedom struggles. For example, you use epigraphs from Toni Morrison and Nina Simone. In “Laugh,” you write: “Atlanta showed me / my first pig carriage in flames.” How do you understand the entanglement of the movements for Black liberation and Palestinian freedom?

MK: I am deeply influenced by Black liberation struggles. I don’t think our campaign this year—the global shift in rhetoric, people taking to the streets all around the world—would have been possible had it not been for the uprisings following the murder of George Floyd. That was the first time I’d seen abolition discussed repeatedly on TV, or widely inside American households. I think that emphasis on the need for a total shift prepared the world for the idea of decolonization from the river to the sea.

CS: You explicitly refuse models of change that require negotiating with the powers responsible for the status quo. In the book’s afterword, you write that, ultimately, the collection’s “merit relies on negating the politics of appeal.” You then talk about writing against “humanization.” Can you say more about how these regimes of representation reproduce settler colonial orders?

MK: The root of a politics of appeal, or of “humanization,” is the idea that Palestinians innately are not enough. We’re innately scary, bad, evil. And so instead of reporting on the atrocities that Palestinians experience, people are reporting on the humanity that we have to attain by saying, “I, like you, believe in this and this and this. I just wanted to go to school. My sister is young, and my father is old. This is why I shouldn’t be thrown out of my home.” Humanization is a white, Western industry of selling perfect victims—toothless, grateful victims who are not going to act. But if we’re actually going to humanize Palestinians, it would look like this: The Palestinian is human because they, like everyone else, would slap a person who slapped them.

The fact of the matter is, I am a stateless person with a settler from Long Island backed by billionaire organizations in my home. There’s a lethal army that surrounds my community and bombards us every day with tear gas and sound bombs and skunk water. Yet I am the one interrogated about my hostility. I am the one interrogated about this slippery slope of hypothetical violence that’s being assigned to me—only to ignore the real material violence that we face every day. Palestinians need to remember that we are not the defendants here. We are the ones who are oppressed, and we have the right to back our oppressors into a corner and interrogate them, not the other way around.

CS: How do you think about violence and nonviolence in relation to the struggle for Palestinian liberation?

MK: I believe wholeheartedly that if you resist colonial violence, you will be met with more colonial violence. This has been a fact of our experience in Palestine. Whenever we resist the barrier, they erect 16 more. But even if you stand against the wall blindfolded and silent, and try to let the storm pass by you, it will take you with it. I think about Audre Lorde saying, “Your silence will not protect you.” That is certainly true in the Palestinian case. You will inevitably get that paper in your mailbox saying that your house is up for grabs. You will get that paper saying that you should leave the country. You will get that paper calling you into the Shabak investigation room. You are going to pay the price for simply being Palestinian. So it is better to resist. Because when you resist, it means you believe you’re deserving of a future. If you’re fighting off something, if you’re burning tires, that only attests to how much you value your peace. You believe in your right to ambition, your right to dream.

CS: In the poem “Autobiography,” you write: “I’m bored with metaphors.” Palestine is so often abstracted to signify something beyond itself—be it freedom or violence. And yet metaphor is the province of poetry, and your book is filled with them. What does metaphor mean for you?

MK: I am bored with this culture of metaphorizing Palestine. I’ve spent so much of my time dilating and dissecting and dissolving my struggle into bite-sized metaphors to communicate something that I could have just said explicitly. I’ve repeated the same metaphors over and over again—the olive trees as resilience—in the hope that people will finally start listening. And most of the time, it doesn’t work that way. That’s not to critique the beautiful tradition of Palestinian literature, which is full of potent metaphors. I certainly do not shy away from them in this collection. As you said, it’s intrinsic. It’s part of who we are. But at the same time, I wanted to question: Why does the Palestinian need to be communicated through other vehicles in order to be understood? Why can’t the Palestinian just be a Palestinian?

CS: The poet M. NourbeSe Philip talks about the need to put English—which has been used as a technology of extraordinary violence—through a “decontaminating process.” I’m thinking about how some of the routes of appeal you’re rejecting might be structured into the English language itself. What does it mean for you to write in English?

MK: “Decontaminating” is a perfect word. There is not much writing about Palestine done by Palestinians in English, especially compared to the amount of Zionist writing. And there’s not much writing in English authentic to the Palestinian streets. We’re not allowed to say it the way we want—the publication won’t run it, the graduate school advisor would panic. For many years, I noticed in myself a shift that happens between Arabic and English. In Arabic, you are assertive, certain, even militant. In English, you are tentative, appeasing, performing. I hope to write in English in a way that remains authentic to the Palestinian experience.

It’s not just the language itself that’s contaminated, but also the structures of anglophone media. For decades, Palestinians have been confronting this media industry of red herrings. Somebody is killed, a house is stolen, somebody is shelled, but instead of focusing on the violence, you’re backed into a corner—“No, that’s not what we mean”; “No one said this. Stop putting words in my mouth”; “Actually, I’m not this way, and I don’t hate this group of people”—and then your time on air is up. It comes off as a petty fight that’s too complex to care about.

In late 2020, when we were about to start a second wave of advocacy for Sheikh Jarrah, I went through dozens and dozens of articles that were written about the neighborhood a decade earlier. I was shocked at how inaccurate, how racist, how anti-Palestinian they were. Entire articles from well-respected publications talk extensively about Sheikh Jarrah without mentioning a Palestinian, let alone interviewing one.

I’m a better writer in Arabic than I am in English, but when people are researching Sheikh Jarrah ten years from now, I want my voice and other Palestinian voices to be present. Not for the sake of representation, but for the sake of truth.

CS: The poet June Jordan said, “Poetry is a political act because it involves telling the truth.” What does poetry offer you alongside your other ways of moving toward truth and toward freedom?

MK: The idea of truth-telling has been so plagued with bureaucracy. There are all these systems in place to say that you cannot tell the truth unless it’s in a certain format, in a certain genre, in a certain tone, according to certain conventions created by people of a certain race and class. But in a poem, any person can say what they want how they want. When I was 13 or 14, I didn’t know how to write articles. But I could write poems. I could name the villain, the victim, the solution, the disease, the symptom. Naming these things, defining them for myself, has limited my confusion about the world.

Claire Schwartz is the author of the poetry collection Civil Service (Graywolf Press, 2022) and the culture editor of Jewish Currents.