World With No Escape

In his final novel, Last Times, Victor Serge achieved the ethical vision that sometimes eluded him in life.

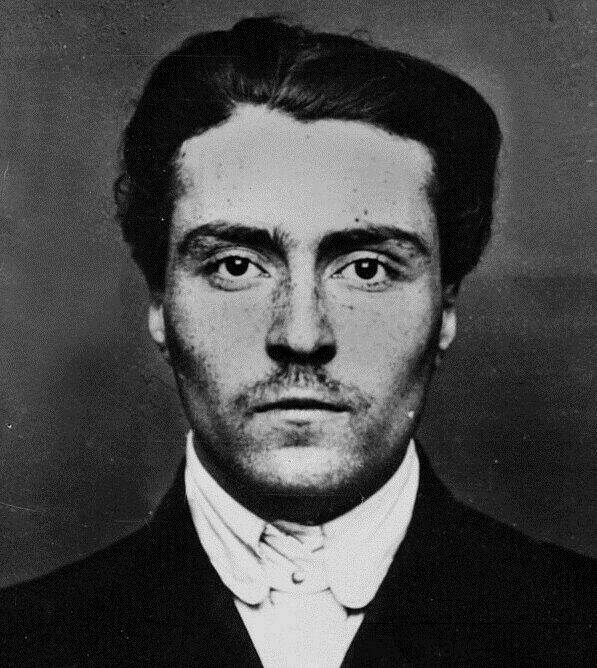

Victor Serge after his arrest in France, 1912.

Discussed in this essay: Last Times, by Victor Serge, translated by Ralph Manheim with revisions by Richard Greeman. NYRB Classics, 2022. 416 pages.

With the arrival of Last Times, we now have full English versions of all seven novels by the great Belgian-born writer and revolutionary Victor Serge. Of these, five have been translated from the French by the Marxist scholar and activist Richard Greeman, who—in addition to translating his novels and Notebooks (the latter in collaboration with the author of these lines)—has spent more than 50 years garnering widespread recognition for Serge. Once all but forgotten even in the French-speaking world outside of small radical circles, Serge is now an international icon of independent, anti-Stalinist leftism. There is no more striking proof of his intellectual stature than Susan Sontag’s laudatory 2004 essay “Unextinguished,” which lamented Serge’s “obscurity” while celebrating him as “one of the most compelling of twentieth-century ethical and literary heroes.”

Though Memoirs of a Revolutionary, an account of his life from his beginnings in Belgium to his final home in Mexico City, has become his best-known book, it was his fiction that Serge valued most highly. Their guiding ethos is perhaps best captured by a title Serge used for a chapter of his memoirs: “World With No Escape Possible.” His novels repeatedly trace the collapse of hopes and societies, from the disabused vision of revolutionary Russia in Conquered City (1932) to the rise of Stalinism in The Case of Comrade Tulayev (published posthumously in 1948). Last Times—his final book, written in exile in Mexico City—takes place against the backdrop of France’s military, political, and moral debacle in the face of the German invasion and occupation in June 1940. Serge lived through most of the period described in the novel in Paris and Marseille, where he endured the harrowing wait for a visa to flee France. (He finally obtained one in 1941, thanks to the work of the American journalist Varian Fry and his refugee aid organization.) Originally published in Montreal in 1946, Last Times appeared in English the same year—the only English translation printed in the author’s lifetime—but this edition was something of a botch; the text was disastrously edited by the publisher. As he did with Serge’s memoirs, which had been translated into English in mutilated form, Greeman completed the work others began, in this case returning to the original text to correct and amend the work of Ralph Manheim, the initial translator.

Last Times is a broad fresco of France in 1940 and 1941, told through a range of characters spanning every strata of French society and centered largely on one Paris street, the fictional Rue du Roi-de-Naples, with its residents, shopkeepers, police, soldiers, foreign political exiles, and Jews threatened by the Nazis’ arrival. Serge, as history’s witness, splits himself among a few characters: There are pieces of him in the opposition communist Kurt Seelig, the aging Russian revolutionary Dr. Ardatov, and the poet Felicien Murier, whose openness, intelligence, and insight echo Serge’s own. The novel’s large cast allows Serge to paint an expansive portrait of contemporary reactions to the disastrous events engulfing the country.

But while Serge’s gaze is panoramic, his sympathies are not equally distributed. His distaste for the shopkeeper mentality, and its resentments both petty and grand, is clear. The petite bourgeoisie understood the quick crumbling of the army, much of it positioned behind the supposedly impregnable Maginot Line, as a result of France having been weakened by social measures implemented by the socialist-led Popular Front. In the minds of the shopkeepers, the French, made soft and spoiled by basic worker protections, were unable to stand up to the unbridled energy of hard, disciplined Nazi Germany. As one of them says, “It serves us right . . . We were taking it too easy, the forty-hour week, paid vacations, the Ministry of Leisure Time—why not a ministry of pleasure, if you please, and free whorehouses for the working class?” Serge sees this form of French self-flagellation for what it is: the entering wedge of fascist ideology. Accordingly, this tendency also finds expression in the desire to purge France of the noxious elements that supposedly brought the invasion about. Last Times describes how squealing was a national plague under the German occupation and the compliant Vichy regime. Leftists and foreigners and Jews were denounced to the police—and, as Serge makes clear, so were totally innocuous individuals who had done nothing but annoy a vindictive neighbor.

Last Times also functions as a gimlet-eyed portrait of the internal workings of the left and the life of a political exile, both of which Serge knew in his flesh. These themes come to the fore in the novel’s depiction of a concentration camp based on those the French maintained even before the German invasion; the camps held foreigners of various kinds, including leftists, Jews, and Spanish Republicans and their allies from around Europe who’d fought in the civil war of 1936–1939. Upon the Germans’ arrival, those held in camps such as Gurs—the infamous site near the Pyrenees where the philosopher Hannah Arendt was detained—were in grave danger. The Vichy government ultimately turned them over to the Nazis by the thousands. Rare in reality were cases like the one in Last Times where an army officer decided to turn a blind eye to the mass escape of a group of political prisoners. Sadly, as Serge shows, the leftist prisoners organized themselves against one another as well as against their shared enemies. In the novel, the Communist leaders plot underhandedly to kill an opposition leftist even as independent revolutionary socialists gather their forces as they prepare to carry on the fight.

If Last Times exemplifies the virtues of Serge’s writing—his shrewd historical insight and his knowledge of the hearts and minds of even those for whom he has little sympathy—it also features many of the weaknesses that can be found elsewhere in his fiction and Notebooks, appearing here in especially magnified form. His prose suffers from verbosity, a refusal to let nouns stand without an accompanying adjective that seldom adds anything. In a description of a ship moving across the sea toward the novel’s end, for instance, he writes: “The universe was all oscillating immobility, airy glow, torrid.” This prolixity belongs not only to the book’s narrator, but also to its characters. The novel is rife with tedious longueurs, set pieces in which characters give themselves over to sermonizing. In these moments, what passes for profundity is really intellectual triteness that leads nowhere. Serge was a novelist of ideas, but not all of them were brilliant.

Serge arrived in Mexico City, where Last Times was written, in 1941. It was not the first time he’d found himself a political refugee. He left Belgium in 1909 under circumstances that are still not clear, was expelled from France to Spain in 1917 after serving five years in prison for his marginal role in the case of the anarchist Bonnot Gang, and returned illegally to France, where he was again imprisoned, before leaving for Soviet Russia in 1919 as part of a prisoner exchange. For a period he served as a right-hand man of Grigory Zinoviev, the head of the Communist International. But his political positions ultimately put him at odds with the Party, and by 1933 he wound up in a Soviet prison camp, from which he was eventually freed thanks to an international campaign. His later exile in Mexico was likewise arduous. He was poor and isolated: While he was part of Mexico City’s exile community—which included French, Spanish, German, and Austrian leftists—these comrades lived in a closed world, isolated from Mexican political reality. Serge and his fellow anti-Stalinist radicals daily confronted irrelevance, threats from the Mexican Communist Party (which directly participated in one of the assassination attempts against Leon Trotsky), and serious internal rifts.

In his Notebooks, which span Serge’s final days in Europe as well as this period, he expressed strong views on these internecine disputes. He was frustrated with his comrades, whom he felt viewed events in Europe too dogmatically. They believed that just as World War I led to the Bolshevik Revolution—and other, failed revolutions—World War II would inspire a wave of leftist revolts. But Serge saw that fascism and war had demoralized the working class, and that the most radical and politically energized workers were under the sway of the Communists and therefore the USSR, which he understood as having become irredeemably totalitarian. (His anti-Soviet sentiments notwithstanding, according to the unpublished accounts of other Mexican exiles, Serge did not hold back from boasting about his former contacts at the center of Soviet power.) Revolution, Serge believed, was simply not in the cards, and much to the chagrin of his fellow exiles, he did not hide his frustration about this state of affairs. In early October 1944, Serge wrote in his Notebooks:

I’m in conflict with many comrades, with the most active who, it is true, are also the least educated . . . Their fidelity to formulas I consider out of date, and from which I think socialism will die if it doesn’t succeed in renewing itself, makes them hostile to me. To such a point that in debates they cease to understand me.

But Serge’s comrades felt that, whatever his past accomplishments, whatever his sufferings under Stalin, and however astute and courageous he was, his situation differed little from their own. They, too, had been forced to abandon their homes, had been imprisoned and faced torture; what gave Serge any right to dictate to them? Because of his tendency to pontificate and condescend to others, they referred to him behind his back as “The Pope.” The conflict came to a head on October 13th, 1944, at a meeting of the exiles’ International Socialist Commission, when the Polish Jewish writer and far-left activist Jean Malaquais rose and expressed his opinion of Serge’s political line. “It seems to me,” he said, “that Victor places his hope in English Tories and liberals.” Serge shouted in response, “You are of a rare dishonesty.” When the meeting was adjourned and the two men reached the street, Malaquais angrily responded, “You accuse me of rare dishonesty while you, in your relations with the comrades . . . ” Before he could finish, Serge seized Malaqauis by the lapels. The dispute escalated from there, until Serge grabbed Malaquis’s wife Galy, who had also attended the meeting, and shouted: “If you weren’t a woman I’d slap you.”

While Serge could be forgiven for acting inappropriately when provoked, it’s harder to excuse the way he responded in the weeks that followed. After a letter from Malaquais sent the next day accused Serge of “hav[ing] become a right reformist,” he requested that Malaquais be sanctioned by the International Socialist Commission. In mid-November Serge wrote a letter to the leadership of the émigré group alleging that “Malaquais does not belong to any socialist organization and isn’t active in any serious circumstance” and, most damning of all, that he “is an Israelite refugee rather than a political refugee.” A left-wing group, Serge implies, has no reason to take seriously someone driven from his home only for being a Jew. On Serge’s request, a commission was set up to arbitrate the dispute; when it failed to condemn Malaquais, Serge resigned from the organization, but not before sending it a letter accusing it of “continuing the demoralizing customs of the Comintern”—that is, of Stalinism. (A harsh charge to level against people whose lives had been threatened by Stalinists just as Serge’s had.)

The callousness toward Jewish refugees that Serge exhibited in the aftermath of his fight with Malaquais is all the more shocking in light of the sympathy on display in his work. Indeed, Serge, whose second wife was the daughter of a Jewish anarchist, distinguished himself for his sensitivity to the plight of the Jews, which he wrote about often. (A whole collection of his writings on European Jewry was recently published in France.) In Last Times, which he was drafting at the same time that this contretemps unfolded, the brutality and precariousness of the Jews’ condition is a constant note: The novel’s Jewish characters are held hostage and executed as they struggle to do everything possible to escape the Germans. In his writings Serge was able to achieve an ethical vision that, as the Malaquais affair demonstrates, he couldn’t always live up to in his personal life. And if revolutionary unity proved elusive in reality, Serge could at least grasp it in fiction. Last Times concludes with a group of characters standing up against oppression and joining the Resistance. Their resolve is palpable. “Jacob, Jacob, will you believe it?” one comrade says to another on the final page. “Today is a day of joy for me. We’ll get through.” “A day of joy,” comes the reply. “Yes.”

In November of 1947, just a few years after he wrote these words, Serge died of a heart attack in the back seat of a Mexico City cab. Only 56 years old, he was so poor he had holes in the soles of his shoes. He died stateless, which was how he lived almost his entire life, and was buried among Spanish Republican exiles. Because his cemetery plot wasn’t purchased in perpetuity, his remains were later dug up. It’s oddly fitting that this eternal exile continued his wanderings after his death.

Mitchell Abidor, a contributing writer to Jewish Currents, is a writer and translator living in Brooklyn. Among his books are a translation of Victor Serge’s Notebooks 1936-1947, May Made Me: An Oral History of My 1968 in France, and I’ll Forget it When I Die, a history of the Bisbee Deportation of 1917. His writings have appeared in The New York Times, Foreign Affairs, Liberties, Dissent, The New York Review of Books, and many other publications.