What the UAW Ceded in Endorsing Biden

Union leaders have not only betrayed their ceasefire call, but also backtracked on their fight to redefine the labor movement as a truly political force.

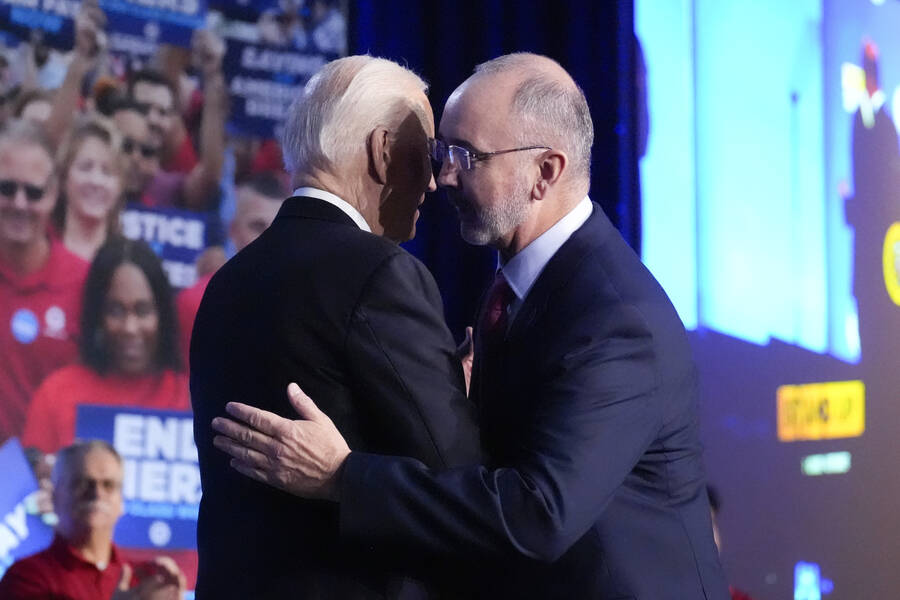

Shawn Fain, head of the United Auto Workers, embraces Joe Biden after endorsing him for president on January 24th.

On December 1st, nearly eight weeks into Israel’s genocidal war on Gaza, the United Auto Workers (UAW) became the largest US labor union up to that point to call for a permanent ceasefire in Israel/Palestine. The announcement—which came on the heels of the UAW’s most successful strike in generations—was celebrated across the left, especially because the union combined it with the creation of a “Divestment and Just Transition Working Group” that promised to not only investigate the union’s financial ties to Israel, but also consider how UAW members working in the weapons industry could be supported in transitioning to peaceful jobs, a shift referred to as “peace conversion.” As the months passed, UAW leaders, including union president Shawn Fain—the winner of the union’s first-ever direct election, who had recently come to office on a platform of internal democracy—continued reiterating these anti-war statements, appearing at ceasefire events alongside Reps. Cori Bush and Rashida Tlaib and touting the union’s position in the press. According to labor historian Jeff Schuhrke, this approach differentiated the UAW from other unions, “which had put out ceasefire statements but then avoided talking about them.” The UAW, he said, “seemed to be running towards the issue, not away from it.”

But on January 24th, just as observers were beginning to hope that the union’s aggressive messaging would translate into concrete action, Fain announced that the UAW would endorse President Joe Biden for reelection. For many rank-and-file members, Fain’s surprise decision, which promised the UAW’s considerable electoral might to a politician being tried for genocide, signaled a complete betrayal of the union’s own ceasefire call. Indeed, members affiliated with the rank-and-file formation UAW Labor for Palestine (of which I am a member) responded to Fain’s endorsement by disrupting the Biden ensuing speech with chants of “ceasefire now!”; three workers were subsequently dragged out of the venue by the Secret Service. Despite these protests, UAW leaders have stood by their decision, which they say was the only way to defend the US labor movement from its most pressing existential threat: a Trump presidency. “Donald Trump stands against everything the UAW stands for,” Fain said, adding that in contrast, Biden had “earned” the UAW endorsement by taking more pro-union stances. In a statement, UAW regional leader Brandon Mancilla similarly held that while he had “deep reservations” about Biden’s policies in Gaza, “ultimately, [UAW leadership] is united behind our belief that a return of Donald Trump . . . would devastate much of the hard-won progress labor is beginning to make in recent years.”

A Trump presidency would certainly be disastrous for unions: His dismal track record on labor—including the appointment of anti-union judges and tax cuts for union-busting corporations—makes this clear, even to UAW members dismayed by the Biden endorsement. “Donald Trump needs to be opposed,” said UAW member and UAW Labor for Palestine organizer Adithya Gungi. “But this does not mean a full-throated endorsement of a Democratic president who has been actively supporting a catastrophic genocide in Palestine.” Members like Gungi take issue with the timing of the Biden endorsement, which unwisely concedes all the UAW’s leverage over the president—leverage which had grown due to the union’s successful 2023 strike in the Rust Belt states, where Biden faces dire electoral weaknesses. In conceding this power over the president, the UAW also appears to have backed away from a radical horizon conjured by its own ceasefire announcement. For decades, US unions have concerned themselves with winning incremental improvements to working conditions while ceding broader production and distribution decisions, as well as questions of policy, to bosses and governments. But in recent months, the UAW was so persistent in its anti-war statements that observers predicted the union might buck this longtime arrangement and become the vanguard of a new working-class foreign policy. The union’s mentions of peace conversion were particularly powerful in this regard, as they gestured to a world in which workers who make weapons could instead push to produce socially useful goods: in other words, a world where workers could exert power not only over their own pay and benefits, but over political—and even geopolitical—decisions about what their labor is used for, and what kind of economy it serves.

These hopes were high in part because, under Fain, the UAW had recently wielded its political capital to intervene in economy-wide production decisions on another front: climate. Throughout last year, the union used its significant leverage over Biden to push him to support its workers in the car industry’s transition to green jobs. When Biden announced his entry into the presidential race last May—and was endorsed by several other national unions within hours—Fain vocally withheld the UAW’s support, “telling members, reporters and anyone else who’d listen that he wanted more help from the White House” prior to backing the president, as a recent cover story in Bloomberg Businessweek recounted. Fain emphasized even then that “another Donald Trump presidency would be a disaster,” but nevertheless said in a memo to UAW members that he “need[ed] to see an alternative that delivers real results” before throwing his weight behind Biden. Specifically, Fain was concerned that the Biden administration was incentivizing car makers to transition from making gas-powered vehicles to electric vehicles (EVs), but was not ensuring that the new EV jobs would be unionized. As a result, auto companies would be able to close down their unionized car plants, set up non-union EV ones, and benefit from government subsidies in the process. “The EV transition is at serious risk of becoming a race to the bottom,” Fain’s memo read. “We want to see national leadership have our back on this before we make any commitments.” According to Bloomberg, Fain said the same to Biden’s face in July 2023, responding to the president’s insistence that he “was doing his part to support autoworkers” by quipping, “We don’t agree.”

In this case, Fain creatively leveraged an endorsement—even in the face of the Trump threat—to advance the union’s most radical aims. He did so despite the fact that the UAW’s push for a just transition to climate-friendly jobs fell outside what many would consider unions’ purview. His strategy therefore claimed for the working class the right to influence climate policy and shape the coming energy transition. And his antagonistic approach to Biden got results. Just a month after Fain spoke directly to the president, the Department of Energy announced that it would distribute an additional $12 billion in subsidies to auto factories moving into making hybrids and EVs—and said that it would prioritize union shops with higher-paying jobs in disbursing the funding. Observers have widely attributed this shift to the UAW’s political pressure on the administration, with CNN saying the move was designed “to win over the powerful United Auto Workers union, which has thus far withheld its endorsement.” A month later, in an even more visible bid for support, Biden showed up to the UAW’s strike, becoming the first sitting president ever to walk a picket line. “If the UAW had endorsed Biden before the strike, I don’t think Biden would have shown up to the picket line,” said Schuhrke. “Fain had leverage, and he used it.” Biden’s visit increased the pressure on the auto companies, and they eventually settled a favorable deal with Fain in October.

Crucially, withholding the endorsement didn’t just make concrete wins possible for autoworkers and the climate movement—it also set the groundwork to move the Rust Belt away from Trump, who has tried to capitalize on autoworkers’ concerns that Biden’s green transition policies will impact their livelihoods. As Fain told Bloomberg, “our workers’ experience right now with this EV transition is not a good thing. So when somebody else comes along and says, ‘Get ready to watch your jobs disappear,’ that is gonna resonate.” In this situation, effectively shoring up support for Democrats means not simply declaring that workers should vote for Biden, but actually demonstrating that Democrats can protect workers’ jobs amid the mounting climate crisis. Even Biden advisors give the UAW credit for helping achieve this goal, with one telling Bloomberg that Fain’s recent campaign—which challenged both bosses and politicians to do more—might have given the green energy transition “fighting odds” with workers. Fain’s approach represents a significant departure from precedent: As Jacobin’s Alex Press has written, the labor movement “has long been tied hook, line, and sinker to the Democratic Party, with labor leaders rarely antagonizing the party’s leadership.” The UAW’s green transition campaign showed a different path forward: one where unions could go from rubber-stamping Democratic candidates to pushing them towards policies that deliver working-class wins and shore up an antifascist base.

To be sure, withholding a Biden endorsement in 2024—with the presidential election just under nine months away—might seem like a different proposition than doing so in 2023, especially with Trump winning decisive victories in early primaries while Biden’s popularity hits record lows. But these considerations need not have precluded the UAW from reprising its creative, and successful, use of leverage. Schuhrke pointed out that UAW leaders could have signaled “that they were prepared to endorse Biden as soon as he did more to push for a ceasefire”—a gesture that could still have been accompanied by strong anti-Trump messaging and campaigning. The UAW could also have leveraged its endorsement in ways that advanced internal union democracy, the signature issue Fain and his reform slate ran on last year. For example, the union could have asked the presidential candidate it was considering endorsing—that is to say, Biden—to participate in a town hall where he answered UAW members’ questions about his alignment with the union’s stances. “We missed the chance to get members and Biden face-to-face,” said New York-based UAW member and UAW Labor for Palestine organizer Zachary Valdez. Putting Biden alone in front of members would have signified that endorsing Trump was never a possibility while significantly pressuring Biden to move towards a ceasefire—which, in turn, might be the only way the president can win back lost votes in states like Michigan. However, instead of giving space to these complex considerations of leverage—a task they took on so well in 2023—UAW leaders defaulted to the same “lesser of two evils” messaging that forms the cornerstone of the Democratic Party’s flailing reelection campaign, and in doing so recommitted to a Democratic status quo they have themselves shown to be worth disrupting on moral, material, and strategic grounds.

In the process, UAW leaders have backtracked on their fight to redefine unions as a truly political force, vehicles with which the working class can exert its influence over the world its labor builds. In their most visionary iterations, US unions have repeatedly reached for this capacious understanding of their role, insisting that in a globally integrated system of accumulation, everything—even foreign policy—is a “bread-and-butter issue.” As historian Aziz Rana has shown, in the early 20th century, radical formations like the Industrial Workers of the World and the Socialist Party acted on this realization by “assert[ing] their own independent foreign policy,” which was staunchly anti-imperialist and anti-war, whether in its opposition to US involvement in World War I or in efforts to organize workers across national borders. In its most ambitious version, the UAW’s ceasefire call—and, especially, its gesture toward peace conversion—recalled this era of labor militancy, when US workers refused to pit their material interests against the common good of their class. By building on its own success in uniting climate and class demands, the UAW was well-positioned to continue expanding labor’s influence over political life while simultaneously protecting its members and actualizing solidarity with workers abroad. Instead, union leaders seem to have recommitted to labor’s Faustian bargain, under which US workers agree to narrow their ambitions in exchange for a slightly larger chunk of the imperial pie.

Aparna Gopalan is news editor at Jewish Currents.