The Hindu Nationalists Using the Pro-Israel Playbook

Inspired by Jewish groups that cast criticism of Israel as antisemitism, Hindu American organizations are advancing a concept of “Hinduphobia” that puts India beyond reproach.

Attendees at the “Howdy Modi” summit in Houston, September 22nd, 2019. Photo: Todd Spoth

Every August, the township of Edison, New Jersey—where one in five residents is of Indian origin—holds a parade to celebrate India’s Independence Day. In 2022, a long line of floats rolled through the streets, decked out in images of Hindu deities and colorful advertisements for local businesses. People cheered from the sidelines or joined the cavalcade, dancing to pulsing Bollywood music. In the middle of the procession came another kind of vehicle: A wheel loader, which looks like a small bulldozer, rumbled along the route bearing an image of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi aloft in its bucket.

For South Asian Muslims, the meaning of the addition was hard to miss. A few months earlier, during the month of Ramadan, Indian government officials had sent bulldozers into Delhi’s Muslim neighborhoods, where they damaged a mosque and leveled homes and storefronts. The Washington Post called the bulldozer “a polarizing symbol of state power under Narendra Modi,” whose ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is increasingly enacting a program of Hindu supremacy and Muslim subjugation. In the weeks after the parade, one Muslim resident of Edison, who is of Indian origin, told The New York Times that he understood the bulldozer much as Jews would a swastika or Black Americans would a Klansman’s hood. Its inclusion underscored the parade’s other nods to the ideology known as Hindutva, which seeks to transform India into an ethnonationalist Hindu state. The event’s grand marshal was the BJP’s national spokesperson, Sambit Patra, who flew in from India. Other invitees were affiliated with the Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (HSS), the international arm of the Hindu nationalist paramilitary force Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), of which Modi is a longtime member.

A wheel loader decorated with photos of BJP leaders appears at Edison, New Jersey’s India Day Parade, August 14th, 2022.

Residents watch as a bulldozer razes storefronts and homes in Delhi’s Jahangirpuri neighborhood, April 20th, 2022.

Initially, New Jersey politicians—including Senators Cory Booker and Bob Menendez and Edison mayor Sam Joshi—decried the parade. In September, the Teaneck Democratic Municipal Committee, a local wing of the New Jersey Democratic Party, passed a resolution condemning the event and calling for a crackdown on what they described as Hindu nationalist groups’ operations in the state. The resolution alleged ties between several Hindu organizations—including a prominent Washington, DC-based advocacy group called the Hindu American Foundation (HAF)—and the RSS, and called on the FBI and CIA to “step up [their] research on foreign hate groups that have domestic branches with tax-exempt status.” It also called for the revision of anti-terrorism laws to “address foreign violent extremists with speaking engagements in the US.”

But soon after the Teaneck resolution was adopted, nearly 60 Hindu American groups released a statement that shifted the conversation away from rising Hindu nationalism toward fears of Hindu victimization. The signatories—who made no mention of the wheel loader, Modi, or the RSS—claimed that the “hate-filled” Teaneck resolution “[demonizes] the entire Hindu American community.” A couple of weeks later, Hindu activists sponsored ten billboards in north and central New Jersey calling on Democrats to “Stop bigotry against Hindu Americans.” Before long, lawmakers began to denounce the resolution. Teaneck mayor James Dunleavy and New Jersey Democratic Rep. Josh Gottheimer came out against the “anti-Hindu” Teaneck resolution; the New Jersey Democratic State Committee soon followed. In the coming weeks, Booker and Menendez both released statements condemning “anti-Hinduism.”

The Teaneck incident is one of many in which Hindu groups have worked to silence criticism of Hindu nationalism by decrying it as anti-Hindu or “Hinduphobic.” In 2013 and again in 2020, a coalition of such groups used allegations of “anti-Hindu bias” to prevent the passage of House Resolutions 417 and 745, both of which criticized Modi. In 2020, when progressives objected to then-presidential candidate Joe Biden’s decision to appoint Amit Jani, a close supporter of Modi, as his director for Asian American Pacific Islander outreach, the HAF denounced these criticisms as an example of “Hinduphobia.” (Biden retained Jani despite the protests.) “The Hindu right wants to distract from India’s catastrophic human rights record,” Audrey Truschke, a South Asia historian at Rutgers University, told Jewish Currents. “So there’s a lot of value in portraying Hindus as victimized people.”

“The Hindu right wants to distract from India’s catastrophic human rights record. So there’s a lot of value in portraying Hindus as victimized people.”

The HAF, the most influential Hindu American advocacy group, has spearheaded a number of these campaigns. Since its founding in 2003, the organization has been known for its work on Hindu civil rights issues; it has pushed for workplace religious protections, school holidays during Hindu festivals, and immigration reform for skilled professionals. But in recent years, it has increasingly sought to raise awareness about what it describes as a new form of anti-Hindu bias. HAF executive director Suhag Shukla told Jewish Currents in an email that while anti-Hindu sentiment in the US used to be animated by “anti-immigrant xenophobia or rooted in colorism, rather than specifically being about Hindus or Hinduism,” recent manifestations of anti-Hindu hatred are “paralleling political tensions arising in India,” and include “terminology and tropes” that originate in sectarian conflict in South Asia.

“What the HAF is trying to do is to conflate Hindutva with Hinduism—to prove that a criticism of Hindutva is an attack on Hinduism,” said the Kashmiri American journalist Raqib Hameed Naik. “There is no doubt that the HAF subscribes to the ideology of Hindutva.” Asked to respond, HAF senior communications director Mat McDermott repeatedly called the allegation “nonsense.” “HAF does not, either officially or unofficially, ‘subscribe’ to Hindutva as an ideology,” he wrote in an email to Jewish Currents. At the same time, he allowed that the organization sometimes finds itself at odds with critics of Hindutva, who “regularly use the term as a slur against people they disagree with and at times against anyone who simply stands up for Hinduism, regardless of that person’s actual political beliefs.”

To counter what they view as a rising tide of prejudice, the HAF and other Hindu American groups have turned to American Jewish organizations, which they have long seen as “the gold standard in terms of political activism,” as Maryland State Delegate Kumar Barve said in 2003. Since the early 2000s, Indian Americans have modeled their congressional activism on that of the American Jewish Committee (AJC) and AIPAC; Indian lobbyists have partnered with these groups to achieve shared defense goals, including arms deals between India and Israel and a landmark nuclear agreement between India and the US. Along the way, these Jewish groups have trained a generation of Hindu lobbyists and advocates, offering strategies at joint summits and providing a steady stream of informal advice. “We shared with them the Jewish approach to political activism,” Ann Schaffer, an AJC leader, told the Forward in 2002. “We want to give them the tools to further their political agenda.” Shukla told Jewish Currents that the HAF continues to work closely with the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) and the AJC, whether by “being co-amici curiae on briefs to the US Supreme Court,” or by “lending our support to one another’s letters to Congress.”

Faced with rising scrutiny over India’s worsening human rights record, Hindu groups have used “the same playbook and even sometimes the same terms” as Israel-advocacy groups, “copy-pasted from the Zionist context,” said Nikhil Mandalaparthy of the anti-Hindutva group Hindus for Human Rights (HfHR). Hindu groups have especially taken note of their Jewish counterparts’ recent efforts to codify a definition of antisemitism—the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) working definition—that places much criticism of Israel out-of-bounds, asserting that claims like “the existence of a State of Israel is a racist endeavor” constitute examples of anti-Jewish bigotry. In April 2021, the Rutgers University chapter of the Hindu Students Council (HSC)—which the RSS has referred to as its “torch bearers abroad”—held a conference to generate a “robust working definition” of the term “Hinduphobia.” (The HSC did not respond to questions.) In an email to Jewish Currents, the HAF’s Shukla wrote that the effort was “similar to members of the Jewish community coalescing around the IHRA working definition of antisemitism.” The resulting definition refers to Hinduphobia as “a set of antagonistic, destructive, and derogatory attitudes and behaviors towards Sanatana Dharma (Hinduism) and Hindus that may manifest as prejudice, fear, or hatred.” Its examples of Hinduphobic speech—which were reiterated at an event in December by HAF managing director Samir Kalra—include “calling for the destruction and dissolution of Hinduism” and using ethnic slurs (Kalra cited examples like “cow-piss drinker,” “dothead,” and “heathen”). Although the definition never names India or the political project of Hindutva, its examples also include “accusing those who organize around or speak about Hinduphobia . . . of being agents or pawns of violent, oppressive political agendas”—a characterization that is regularly applied to efforts to call out Hindu nationalist activity, such as the Teaneck Democrats’ resolution.

Although the Rutgers definition of Hinduphobia never names India or the political project of Hindutva, its examples include “accusing those who organize around or speak about Hinduphobia . . . of being agents or pawns of violent, oppressive political agendas”—a characterization that is regularly applied to efforts to call out Hindu nationalist activity.

Volunteers of the Hindu nationalist paramilitary group the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) take a pledge during an event at their headquarters in Nagpur, India, June 7th, 2018.

On the HAF’s website, a glossary of Hinduphobic terms includes the word “Hindutvavadi,” or “someone who espouses or promotes Hindutva,” which the HAF says is “intended to demonize Hindu Americans and delegitimize the causes they advocate for.” It also contains the epithet “Bhakt,” or “devotee,” slang in India for die-hard supporters of the BJP, which the glossary says “presents Hindus through a simplistic, political binary of for or against,” adding that the term’s use “in conjunction with portrayals of Narendra Modi and his political party as supremacist or fascist” are “particularly egregious.” Naik called this logic “absurd”: “How can one take a criticism of a hateful ideology and conflate that with a religion?”

Despite such contradictions, the concept of Hinduphobia has enjoyed a meteoric rise in usage in the wake of the Rutgers conference, gaining ground against terms like “anti-Hindu” or “anti-India” in the US. “I saw it grow over the past three or so years,” said anti-Hindutva advocate and journalist Pieter Friedrich, whose activism has recently been labeled “Hinduphobic” by the HSS and its affiliates. Before the Rutgers conference had even ended, the university’s student government became the first in the country to adopt the working definition as part of the guidelines for the school’s existing grievance process. In the past two years, the student group Hindu on Campus has used the definition to target “Hinduphobic” individuals at universities across the country, even launching a Campus Hinduphobia Tracker in collaboration with conference organizers. In September, the Coalition of Hindus in North America (CoHNA)—a new Hindu advocacy group involved in publicizing the term Hinduphobia—organized a congressional briefing on the subject. The event, which advanced the argument that labeling Hindus pro-Hindutva amounts to persecution, was attended by Georgia’s Republican Rep. Drew Ferguson, a supporter of Donald Trump. In September, Rep. Raja Krishnamoorthi, a pro-Modi Hindu Democrat from Illinois, spoke about Hinduphobia on the floor of the House of Representatives; CoHNA celebrated the term’s entrance into the congressional record as a “boost” for their organizing.

These efforts are redefining the terms of the discourse about India at a moment when the country’s image as the world’s largest democracy is in jeopardy. An October 2022 report from Georgetown University’s Bridge Initiative warns that the country is heading toward a full-fledged genocide of its 200 million Muslim residents. Since 2020, the US Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) has repeatedly asked the State Department to recognize India as a “country of particular concern” due to its “egregious” human rights violations against religious and caste minorities and their supporters, including “surveillance, harassment, demolition of property, arbitrary travel bans, and detention.” While the US has not yet heeded the USCIRF recommendation, Secretary of State Antony Blinken said last April that he is monitoring the rise in human rights abuses. If the State Department were to act, India could face sanctions, including the loss of its ability to buy weapons from the US. This is why Hindu nationalist groups in the US are “targeting the critics of Modi’s discriminatory policies and fighting to give the Indian government a free pass for all its violations of human rights,” said Naik. “The Hindu far-right are fooling their community. They are telling them that they’re fighting for Hindu Americans. But what they are fighting for is Hindutva.”

“The Hindu far-right are fooling their community. They are telling them that they’re fighting for Hindu Americans. But what they are fighting for is Hindutva.”

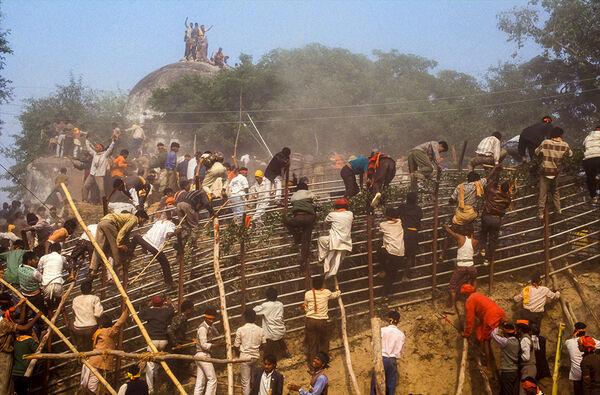

On December 6th, 1992, a mob of 150,000 Hindus, many of whom were affiliated with the paramilitary group the RSS, gathered at the Babri Masjid, a centuries-old mosque that is one of the most contested sacred sites in the world. Over the preceding century, far-right Hindus had claimed that the mosque, located in the North Indian city of Ayodhya, was built not only upon the site where the Hindu deity Ram was born but atop the foundations of a demolished Hindu temple. The RSS and its affiliates had been campaigning to, in the words of a BJP minister, correct the “historical mistake” of the mosque’s existence, a task the mob completed that December afternoon. “They climbed on top of the domes and tombs,” one witness told NPR. “They were carrying hammers and these three-pronged spears from Hindu scripture. They started hacking at the mosque. By night, it was destroyed.” The demolition sparked riots that lasted months and killed an estimated 2,000 people across the country.

The destruction of the Babri Masjid was arguably Hindu nationalism’s greatest triumph to date. Since its establishment in 1925, the RSS—whose founders sought what one of them called a “military regeneration of the Hindus,” inspired by Mussolini’s Black Shirts and Nazi “race pride”—had been a marginal presence in India: Its members held no elected office, and it was temporarily designated a terrorist organization after one of its affiliates shot and killed Mohandas Gandhi in 1948. But the leveling of the Babri Masjid activated a virulently ethnonationalist base and paved the way for three decades of Hindutva ascendance. In 1998, the BJP formed a government for the first time; in 2014, it returned to power, winning a staggering 282 out of 543 seats in parliament and propelling Modi into India’s highest office. Since then, journalist Samanth Subramanian notes, all of the country’s governmental and civil society institutions “have been pressured to fall in line” with a Hindutva agenda—a phenomenon on full display in 2019, when the Supreme Court of India awarded the land where the Babri Masjid once stood to a government run by the very Hindu nationalists who illegally destroyed it. (Modi has since laid a foundation stone for a new Ram temple in Ayodhya, an event that a prominent RSS activist celebrated with a billboard in Times Square.) The Ayodhya verdict came in the same year that Modi stripped constitutional protections from residents of the Muslim-majority region of Kashmir and passed a law that creates a fast track to citizenship for non-Muslim immigrants, laying the groundwork for a religious test for Indian nationality. Under Modi, “the Hinduization of India is almost complete,” as journalist Yasmeen Serhan has written in The Atlantic.

To achieve its goals, the RSS has worked via a dense network of organizations that call themselves the “Sangh Parivar” (“joint family”) of Hindu nationalism. The BJP, which holds more seats in the Indian parliament than every other party combined, is the Sangh’s electoral face. The Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) is the movement’s cultural wing, responsible for “Hinduizing” Indian society at the grassroots level. The Bajrang Dal is the project’s militant arm, which enforces Hindu supremacy through violence. Dozens of other organizations contribute money and platforms to the Sangh. The sheer number of groups affords the Sangh what human rights activist Pranay Somayajula has referred to as a “tactical politics of plausible deniability,” in which the many degrees of separation between the governing elements and their vigilante partners shields the former from backlash. This explains how, until 2018, the CIA could describe the VHP and Bajrang Dal as “militant religious organizations”—a designation that applies to non-electoral groups exerting political pressure—even as successive US governments have maintained a warm relationship with their parliamentary counterpart, the BJP.

Hindu militants destroy the Babri Masjid in Ayodhya, India,

December 6th, 1992.

As the Indian American diaspora has grown—from 9,000 people in 1960 to a million in 1990 to 4.2 million in 2022—similar groups have cropped up in the US, as journalist Azad Essa documents in his book Hostile Homelands: The New Alliance Between India and Israel. The earliest were branches of Indian organizations, such as the VHP-America (VHP-A), which was founded in 1970, and the HSS USA, an arm of the RSS, established in 1989. Their goal was to support their Indian counterparts with funds and political connections—which proved especially crucial when the RSS was banned in India in the mid-’70s and the HSS stepped in to spearhead Sangh organizing from abroad. Energized by the demolition of the Babri Masjid, the groups grew rapidly in the ’90s. Political scientists Christophe Jaffrelot and Ingrid Therwath see this as the moment when “Hindutva gained respectability” in the diaspora, inspiring a surge in donations to Hindu American groups that funneled the money to their Indian counterparts. Hindu right organizations also began working to manage India’s reputation in the US: In April 1992, six months before the Babri Masjid was demolished, then-BJP president Lal Krishna Advani officially launched a US wing of the party, the Overseas Friends of the BJP (OFBJP). According to early OFBJP leader Adapa Prasad, the group worked to counteract “bad press” in the international media, which regularly referred to BJP-adherents as “Hindu militants” and “extremists.” (The group claims it has since played a key role in supporting the BJP’s electoral victories, sending thousands of volunteers to India to campaign for Modi in 2013 and organizing a phone bank of half a million Indian voters from the US.)

As Hindu groups gained their footing in the US, they began to collaborate with their Jewish counterparts, which many Hindus saw as “a model for their own attempt not simply to gain respectability in mainstream America, but to gain power in Washington,” as Vijay Prashad, a prominent left-wing historian of South Asian history, wrote in his 2005 paper “How the Hindus Became Jews.” According to Essa, these relationships took shape in the mid-’90s—when, for example, AIPAC lobbyist Ralph Nurnberger was recruited to head up the new Indian American Center for Political Awareness, which emulated Jewish groups by placing Hindu interns in congressional offices. The alliance grew closer after 9/11, when both Hindus and Jews joined the chorus demanding US military action against Islamic terrorism. The most extreme figures in the Hindu nationalist and Zionist movements were especially frank about the nature of their partnership: “Whether you call them Palestinians, Afghans, or Pakistanis, the root of the problem for Hindus and Jews is Islam,” Bajrang Dal affiliate Rohit Vyasmaan told The New York Times of his friendly relationship with Mike Guzofsky, a member of a violent militant group connected to the infamous Jewish supremacist Meir Kahane’s Kach Party. Members of the political mainstream took a similar view. In 2003, Gary Ackerman—a Jewish former congressman who was awarded India’s third-highest civilian honor for helping to found the Congressional Caucus on India—told a gathering of AJC and AIPAC representatives and their Indian counterparts that “Israel [is] surrounded by 120 million Muslims,” while “India has 120 million [within].” Tom Lantos, another Jewish member of the caucus, likewise enjoined the two communities to collaborate: “We are drawn together by mindless, vicious, fanatic, Islamic terrorism.”

Driven by that sense of shared purpose, the AJC and AIPAC helped train new Indian American political groups—such as the Indian American Political Action Committee and the United States India Political Action Committee—to achieve their aims in Washington. The AJC hosted seminars on political activism in DC and New York; it also brought several delegations of Indian Americans to Israel to meet with members of the Israeli government and military. “We’re fighting the same extremist enemy,” the AJC’s capital region director Charles Brooks told the Forward in 2002. “We want to help them become more effective in communicating their political will.” With the help of their Jewish allies, Indian American organizations pursued goals such as trying to block US aid and weapons sales to Pakistan. While that effort did not succeed, the groups secured other victories, including sales of Israeli and US arms to India and a historic India–US nuclear deal, which essentially exempted India from global nuclear nonproliferation efforts and granted it access to US nuclear technology. Jewish groups were particularly instrumental in the case of the nuclear agreement: Ackerman met repeatedly with President George W. Bush to advocate for the deal, and the AJC pushed members of Congress to support it. The “Indian-Jewish solidarity forged and bolstered over the last quarter-century in the United States,” AJC chief policy and political affairs officer Jason Isaacson argued in a 2017 op-ed for The Jerusalem Post, was an “essential” factor in “the emergence of the trilateral alliance” between India, Israel, and the US.

Driven by a sense of shared purpose, the AJC and AIPAC helped train new Indian American political groups to achieve their aims in Washington.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Hindu American activists also founded a new cohort of organizations focused less on “matters in the ‘homeland’” than on “the terrain of Indian-American life,” as Prashad and the activist intellectual Biju Mathew have written. Many of these new groups were modeled on the ADL, founded in 1913 to oppose discrimination against Jews by monitoring their portrayal in US society. In 1997, the VHP-A established an anti-defamation arm, American Hindus Against Defamation (AHAD), which launched successful campaigns against demeaning uses of Hindu iconography in perfume branding, yoga gear, a Sony commercial, and a Simpsons episode. AHAD’s victories inspired other US-based anti-defamation groups, including the Hindu International Council Against Defamation and India Cause. Focusing on the politics of representation helped Sangh-aligned activists recruit immigrants frustrated by racism and social isolation, according to Prashad and Mathew’s 2000 paper, allowing the Hindu right “to go among the multitude of Indian Americans and attract a few into its organizations and more into its general world-view.”

The most important organization established in this era was the HAF, which consciously drew inspiration from the dual structure of the ADL. The ADL boasts an active civil rights division—focused on racial justice, immigrant rights, LGBTQ equality, and other liberal causes—alongside a lobbying arm devoted to Israel advocacy. The HAF, too, holds liberal positions on domestic civil rights issues while advancing what Shukla characterized as “center-right” positions on “foreign policy, especially security and counterterrorism.” But even though it spoke in what religious studies scholar Shana Sippy calls “a decidedly American register,” the HAF traced its roots to Sangh networks. Several of its early board members had ties to the VHP-A, the HSS, or the RSS-linked Hindu Students Council (HSC): Shukla, for example, began her career in the HSC, which another co-founder, Mihir Meghani, had helped to establish in addition to serving on the VHP-A governing council. Naik, the Kashmiri American journalist, has reported that many of HAF’s donors are leaders in Sangh groups; McDermott called the reporting “categorically false.” In 2019, a member of the HAF’s board, Rishi Bhutada, served as chief spokesperson at the OFBJP-led “Howdy Modi” event featuring Donald Trump and the Indian prime minister. (McDermott noted that Bhutada was acting in a private capacity.) More recently, the HAF joined groups including the HSS, VHP-A, HSC, and CoHNA to host Dattatreya Hosabale, the sitting general secretary of the RSS, at a Hindu Heritage Month event in 2022. (The event web page has since been updated to note that the HAF “is being targeted by several individuals and organizations with a record of anti-Hindu activism . . . to that extent, it should be noted that HAF was not part of the committee that invited the speakers.”)

Although McDermott emphasized that the HAF is “not a supporter of any political party in India nor the United States” and “does not think in terms of right [vs] left in the positions we take,” the group has staked out right-wing positions on Indian politics that align closely with those of the BJP. On Ayodhya, the group “[denounces] the violence that arose in the tearing down of the Babri Masjid and its aftermath,” but supports “the re-establishment of a Hindu temple on the site.” On Kashmir, the HAF declares that the region “always has been and always will be an integral part of the Indian civilizational state,” a line almost identical to that of BJP defense minister Rajnath Singh. And though it professes to focus on Hindus in the US, the HAF’s annual human rights reports exclusively cover Hindu oppression in Muslim-majority places like Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Kashmir; there are no equivalent reports tracking, for example, domestic incidents of racism. McDermott defended the reports, writing that their entire purpose is “to focus on areas where Hindus are a minority and face serious human rights challenges. That many of these places are Muslim-majority shows the very challenges Hindus face in these countries.”

Mandalaparthy argued that the HAF’s “robust track record on LGBTQ, environmental, and reproductive rights” granted the organization “credibility,” even as it “veers into right-wing, foreign policy-focused projects.”

US President Donald Trump and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi greet crowds outside Houston’s “Howdy Modi” event, September 22nd, 2019.

HfHR’s Mandalaparthy argued that the HAF’s “robust track record on LGBTQ, environmental, and reproductive rights” granted the organization “credibility,” even as it “veers into right-wing, foreign policy-focused projects.” Indeed, the HAF is a member of prominent civil rights coalitions such as the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights that includes Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. Truschke argues that the HAF’s legibility as a civil rights organization has allowed it to gain political influence that it can use in its Hindu advocacy: “Politicians who would probably be wary if the HSS walked into their office look at HAF and think, ‘This is a nice Hindu American group.’”

In 2021, more than 70 departments at 53 universities around the world came together to organize a conference about Hindu nationalism, “Dismantling Global Hindutva.” In the weeks leading up to the September event, the HAF and other groups—including the HSS and the VHP-A—agitated their supporters against it. Claiming that the conference promoted anti-Hindu hate and sought to “oppose and ‘dismantle’ the Bharatiya Janata Party, a democratically elected party in India,” the HAF sent letters to 41 universities asking them to “remove” their “names and logos from the event website and promotional materials.” It provided templates that students, parents, and alumni could employ to protest the use of university resources “to promote a partisan event” that “targets an ethno-religious minority,” and drew up a template to help Indian nationals express concern to the minister of external affairs; CoHNA posted similar templates on its own site. In the end, the HAF claimed that “approximately 1 million emails were sent to university administrators through our grassroots campaign.” At Drew University in New Jersey, servers crashed after more than 30,000 emails arrived in a matter of minutes.

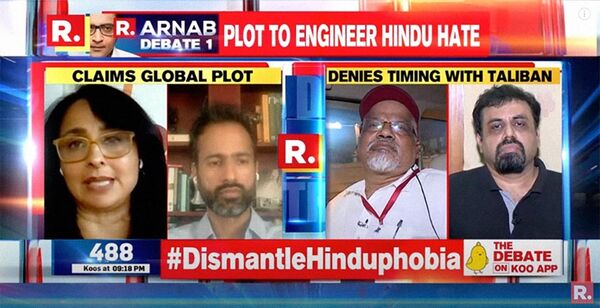

HAF’s Suhag Shukla (far left) appears on the right-wing Indian television network Republic TV in a program discussing whether the “Dismantling Global Hindutva” conference was part of a global Islamist plot, August 24th, 2021.

The conference also became a topic of concern in India: The Hindu Janajagruti Samiti, whose members have been linked to the murder of an Indian journalist critical of the Modi government, wrote letters to Indian ministers seeking action against India-based speakers. When the event was featured on a debate program on one of the country’s most prominent right-wing news channels, Shukla joined the camp claiming that the conference was part of a “global plot” to distract from the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan by attacking Hinduism instead.

Ultimately, the conference went forward, though several speakers pulled out after receiving a barrage of rape and death threats. The following month, the HAF—which recently referred to the event as an “all-you-can-eat-buffet of Hinduphobia”—filed a Title VI complaint against the University of Pennsylvania, one of the event’s co-sponsors. The HAF disputes the way news reports characterized its involvement in opposing the conference. “We never once called for the conference to be stopped,” McDermott wrote to Jewish Currents. “Our efforts were focused on the nature of the statements made about Hinduism.”

The same groups that decried the academic conference have also wielded accusations of Hinduphobia against unfavorable media coverage. In 2021, for example, the HAF sued HfHR, Truschke, and the advocacy organization Indian American Muslim Council for defamation over their critical comments in an Al Jazeera article written by Naik. (The suit was dismissed.) The HAF and the HSS also called Friedrich “Hinduphobic” for attacking Krishnamoorthi’s Sangh ties. The criticisms were picked up by civil rights leader Jesse Jackson, who condemned Friedrich for “making threats against non-white people, especially because of the color of their skin, their religious affiliation, or their country of origin.” As Chicago Sun-Times journalist Rummana Hussain noted, while Friedrich sometimes hurt his own cause with his “brash” style, it was clear that he was “speaking out against oppression in India.” She added that Jackson’s tweets echoed Hindu groups’ talking points.

Some of the organizations’ Hinduphobia campaigns have been directed against opposition to the Indian caste system—which often comes from Dalit activists from that system’s lowest stratum. Downplaying caste oppression is central to the Hindu nationalist project. Historically, some anti-caste leaders have argued that caste-oppressed people should reject Hinduism, which has long relegated them to its margins. Dalit journalist Suprakash Majumdar notes that such anti-caste struggles have the potential to threaten Hindus’ claim to majority status in India, which is foundational to the Hindutva ideology. Hindu nationalist leaders also tend to come from the dominant castes and continue to benefit from the entrenched hierarchy both in India and in the diaspora.

In facing off against anti-caste activists, such Hindu groups generally position themselves as the victimized party, arguing that the critiques in question “scapegoat” Hindus and Hinduism. In 2006, Sangh-affiliated organizations began a months-long campaign to cut mentions of caste discrimination from sixth grade history textbooks in California; that same year, the HAF sued the state in an attempt to get the textbooks thrown out altogether (allied organizations pursued a similar suit in 2017). Asked for comment, McDermott said the HAF supports education about caste discrimination as long as the subject is “taught accurately,” which means not “placing the blame” for the existence of the caste system on Hinduism—a move the HAF has long argued leads to the bullying of Hindu students. But anti-caste activists point out that the HAF and its partners sought not only to remove stereotypes about Hinduism, but to erase acknowledgment of caste altogether. In 2022, the HAF also sued the state of California for pursuing a case about workplace caste discrimination against the tech giant Cisco, arguing that the state was “seeking to define what Hindus believe and decide how they practice their religion, in violation of the First Amendment.”

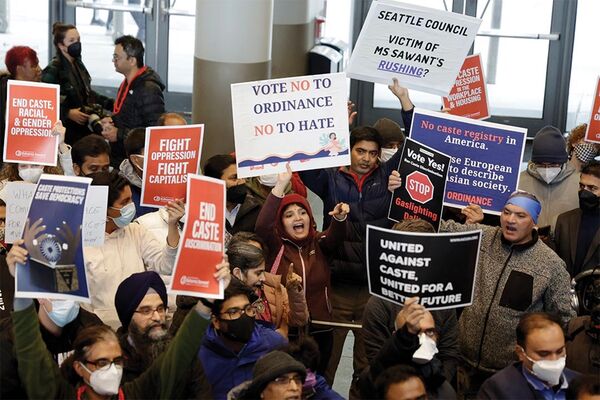

Supporters and opponents of a proposed ordinance to add caste to Seattle’s antidiscrimination laws during a rally at Seattle City Hall, February 21st, 2023.

In February, the Seattle City Council—led by Indian American politician Kshama Sawant—passed an ordinance establishing caste as a protected category, making the city the first US jurisdiction to essentially outlaw caste discrimination. In response, Pushpita Prasad, a board member for CoHNA, told Jewish Currents, the group organized supporters to send 20,000 emails to the Seattle City Council, convinced over 100 mostly Hindu organizations to sign a letter opposing the ordinance, and put together an in-person protest. Prasad called the ordinance “racist and discriminatory” and “classic Hinduphobia.” For its part, the HAF has said it is “investigating all avenues of response to this facially discriminatory policy.” Groups like HAF and CoHNA are also mobilizing against a policy banning caste discrimination that recently passed the California Senate Judiciary Committee. Such efforts frame “the diasporic Hindu community and future generations of North American Hindus [as] the injured,” Sippy writes in a forthcoming book on the collaboration between Jewish and Hindu diasporas.

The HAF has also worked to mainstream the notion that “Hinduphobia” is running rampant in American society. It argues that the present upsurge in anti-Hindu bias is driven in particular by the “international spillover of domestic Indian political sentiment”—which is why, HAF executive director Shukla emphasized, its perpetrators are increasingly of Indian or even Hindu origin. Indeed, each of the Hindu groups I interviewed for this story pointed to the same few instances of this new, politically inflected Hinduphobia, such as an August 2022 altercation in which a Sikh man spat and shouted at a Hindu man in Fremont, California, combining racist comments with references to India’s history of anti-Sikh violence, which has ramped up under the BJP. In September 2022, another man was charged with a hate crime for destroying a statue of Mohandas Gandhi at a Queens, New York, temple; security footage shows that he also referenced the Sikh independence (“Khalistan”) movement. Progressive Hindu leaders oppose such attacks but question whether all of them truly constitute anti-Hindu hate crimes, noting that Gandhi is a regular target for pro-Khalistan activists. “I think it was more anti-Gandhi, not so much as anti-Hindu,” Uma Mysorekar, president of the Hindu Temple Society of North America, told Gothamist about the Queens statue vandalism—a view supported by anti-Gandhi statements made by the perpetrator.

Indeed, the data on anti-Hindu hate crimes undermine the contention that bigotry against Hindus is on the rise. In a recent article, HfHR co-founder Raju Rajagopal points out that of the 35 groups included in the FBI’s hate crimes database, Hindus were less likely to experience hatred than all but Jehovah’s Witnesses. “Muslims are eight times more likely [to experience hate than Hindus are], Jews are 12 times more likely and Sikhs are 128 times,” Rajagopal wrote. (The HAF see this as evidence of underreporting, which they hope to solve by working with law enforcement and “empowering the Hindu American community to recognize, confront, and report Hinduphobia,” Shukla told Jewish Currents.) HfHR notes on its website that though “Hindus globally face varying levels of discrimination,” the data categorically do not support “the notion of systemic Hinduphobia in the United States.” Truschke agreed that the very concept of Hinduphobia seemed “designed to take individual cases and assert a structural problem.” The goal, Sippy argued, is to “cultivate a narrative of Hindu victimization that is robust enough to justify contemporary atrocities.”

Despite efforts to publicize examples of Hinduphobia—and a marked increase in usage over the past few years—the term has yet to enter widely into circulation. Even as Hindu groups described the Fremont incident as a textbook instance of Hinduphobia, for instance, the Hindu man targeted there did not use that language in interviews. “Like most Indian Americans—or most people—he was not even aware of this word ‘Hinduphobia,’” CoHNA’s Prasad told Jewish Currents. Nikunj Trivedi, the president of CoHNA, agreed: “Unfortunately, our own community has certain trauma and denies Hinduphobia because of misinformation they have imbibed.”

Hindu activists support their claim that anti-Hindu persecution is on the rise by pointing to a report on “Hinduphobia on social media” from the Network Contagion Research Institute (NCRI), which studies online hate and manipulation. The report’s principal investigator is antisemitism researcher Joel Finkelstein, whose previous work arguing that anti-Zionism is a form of antisemitism has been spotlighted by groups like the AJC; two of the report’s other authors, Prasiddha Sudhakar and Parth Parihar, are members of the RSS-linked HSC. Published in July 2022, the report concluded that online activity suggested an impending anti-Hindu hate crime surge. In cataloging examples of anti-Hindu hatred, the report makes no distinction between memes that depict Hindus being gassed or decapitated and tweets criticizing Hindu nationalism and warning against an ongoing Muslim genocide in India. Truschke compared it to reports by Israel-advocacy groups, with their “classic jump from, ‘Here’s some real antisemitism’ to ‘Never say anything bad about Israel.’” (The NCRI did not respond to questions from Jewish Currents.)

In cataloging examples of anti-Hindu hatred, the NCRI report makes no distinction between memes that depict Hindus being gassed or decapitated and tweets criticizing Hindu nationalism and warning against an ongoing Muslim genocide in India.

The NCRI report has proved useful to Hindu groups seeking to bring new attention to Hinduphobia: CoHNA highlighted its findings in three separate congressional briefings and a Hindu advocacy day on Capitol Hill, as well as in conversations with individual lawmakers—an effort that culminated in the remarks by Krishnamoorthi that entered the term into the congressional record. Trivedi told me that academic research like NCRI’s is the solution to Hinduphobia’s credibility gap. “What was missing was the institutionalization of the research,” he said. “The idea is to first introduce the topic, then institutionalize the topic, and then popularize it in government bodies and education.” The strategy seems to be bearing fruit: In April, CoHNA spearheaded a resolution condemning Hinduphobia that was approved by the Georgia state legislature; a similar measure recently passed in Fremont, California, the city where the HAF was founded.

The targets of these Hinduphobia campaigns say that their purpose is to create a durable chilling effect. “Part of the goal is intimidation,” said Truschke, who in addition to being sued by the HAF was also targeted by the student group Hindu on Campus, which demanded that she no longer be allowed to teach about Hinduism or India. “Making life difficult for people often dissuades them from certain courses of action.” In her view, this is why Hindu groups mobilize even in situations where criticism doesn’t pose an immediate risk to the Indian government, or to the diaspora groups’ own operations—as in the case of the Teaneck resolution. McDermott called the accusation that the HAF chills anti-Hindutva speech “false. We’ve never once set out to do that.” But the organization’s campaigns appear to have made an impression, even where they have failed to achieve their policy aims. The only city council member who voted “no” on Seattle’s anti-caste law, Democrat Sara Nelson, cited the HAF’s lawsuit against the state of California in a statement explaining her decision. “Speaking as a steward of our public resources, the last thing we need is yet another costly lawsuit,” she said, adding that “singling out Hindus as the perpetrators and victims of caste discrimination will only generate more anti-Hindu discrimination.”

On December 8th, the HAF hosted a webinar with the Israel-advocacy organization StandWithUs, the first event in a three-part series titled “Shine a Light on Antisemitism & Hinduphobia: What Hindus and Jews Can Learn from Each Other.” StandWithUs national director of special programs Peggy Shapiro greeted the audience with a “Namaste.” Shukla followed with a “Shalom.” The exchange kicked off a call-and-response structure that carried through the next 75 minutes, with Shapiro presenting a piece of information about antisemitism, and Shukla following with a sound bite about Hinduphobia. The speakers presented even their personal histories in parallel: After Shapiro introduced herself by saying, “I was born in a refugee camp in Germany. My parents were Holocaust survivors,” Shukla followed with, “I was born in California to parents who had left dire situations in India.” (The HAF did not provide answers to a follow-up question about the conditions under which Shukla’s family emigrated.)

As Shapiro and Shukla traded the mic back and forth, some of their examples sat awkwardly within the event’s parallel structure. Shapiro mentioned the ancient trope of “blood libel,” referring to the medieval belief that Jews used the blood of Christians in their religious rituals; in turn, Shukla pointed to the anti-Hindu bias evident in “a special hatred for . . . Brahmins,” the minority group that dominates India’s caste hierarchy. Other exchanges unintentionally highlighted differences in scale. Shapiro described the Nazi propaganda that depicted Jews as a “menace to the white race”; Shukla mentioned an NPR journalist’s tweet accusing Hindus of “piss drinking.” Shapiro raised the age-old specter of the greedy Jewish merchant; Shukla followed with a 4chan meme in which a Hindu is likewise depicted as avaricious. When Shapiro spoke about synagogue shootings and other acts of violence against Jews in the US, Shukla paused to acknowledge that “the scale of Hinduphobia crossing the line into violence is nowhere close to what the Jewish community faces in the United States.” Nevertheless, Shukla maintained the event’s rhythm, emphasizing that the number of religiously motivated hate crimes against Hindus had risen from eight in 2019 to 11 in 2020.

The event is part of a broader collaboration between the Israel-advocacy group and its Hindu counterpart. In an email to Jewish Currents, Shapiro described Hinduphobia as “a recycling of stereotypes and slurs used against Jewish people,” pointing to caricatures of both groups as devil-worshippers and to “dual loyalty” tropes that accuse both Jews and Hindus of maintaining an allegiance to a foreign homeland. She emphasized that these parallel biases call for parallel solutions. Although the Hinduphobia definition “was created independently of the IHRA Definition, the overlaps are quite remarkable,” she wrote. “We are committed to help [sic] raise awareness [of] Hinduphobia. Our lines of communication are open.” (Asked to respond to the criticism that both the IHRA definition and the concept of Hinduphobia are used to shut down legitimate political speech, Shapiro wrote in an email, “We don’t silence any speech, even hate speech or stupid speech. We use our own rights to speak out against hateful speech.”) In addition to more formal meetings like the joint webinars, Shapiro mentioned that she has hosted Hindu American allies at her home for dinner and conversation. CoHNA’s Trivedi recalled similar gatherings where he laughed with Jewish activists about their mirror-image experiences with Hindus who oppose the term “Hinduphobia” and Jews who “deny” antisemitism.

In the 2010s, as longtime humanitarian activist Sunita Viswanath watched her community lurch rightward in tandem with Modi’s rise, she wondered: Where are the anti-Hindutva Hindus?

Meanwhile, Hindu and Jewish progressives are collaborating as well. In the 2010s, as longtime humanitarian activist Sunita Viswanath watched her community lurch rightward in tandem with Modi’s rise, she wondered: Where are the anti-Hindutva Hindus? In the eyes of her partner, Stephan Shaw, Viswanath was wandering “in the desert of a faith where no one would speak out against the injustice” as Hindus. Shaw recognized the experience: As a Jew who opposed Israel’s occupation, he had spent years in a desert of his own before joining the anti-Zionist group Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP). Finding a “political and spiritual home” in JVP was “liberating and transformative” for Shaw, Viswanath told me. “I resolved to either find or make a similar spiritual community for Hindus of conscience.” She turned to Alissa Wise—former deputy director of JVP—for advice on establishing what Shaw calls a “JVP for Hindus.” Wise agreed to coach the new leadership of what became Hindus for Human Rights, training staff and board members and facilitating retreats—a relationship that recalls the HAF’s decades of collaboration with the ADL and AJC.

Former deputy director of Jewish Voice for Peace Alissa Wise leading a workshop with members of Hindus for Human Rights. Photo courtesy of Hindus for Human Rights.

Since its founding, HfHR has joined a small circle of anti-Hindutva groups in organizing against the Hindu right. To do so, they must contend with the emotional power of the new Hinduphobia strategy. In interviews for this story, sources spoke constantly about their fear. Vamsee Juluri, a University of San Francisco media studies scholar whose work has been used to define “Hinduphobia,” called it an “existential” threat. CoHNA’s Prasad called the NCRI report on online anti-Hindu activity “a foreshadow of real-life violence to follow.” When Seattle passed its ordinance banning caste discrimination, CoHNA board member Sudha Jagannathan told me she would now feel uneasy driving into the city, while Prasad argued that the new law rendered Dalit activists “judge, jury, and executioner” for Hindu Americans, claiming that any complaint of real or perceived discrimination could now deprive Hindus of their jobs, turn their children against them, and, over time, escalate into a full-fledged genocide. Trivedi emphasized that the Hindu American community was not responding with enough alarm to the writing on the wall. “It took a decade for the Nazis to do what they did,” he said. “It wasn’t an overnight thing; it developed slowly.”

Anti-Hindutva groups are debating the best approach to combating what Sippy calls this “affective politics of fear.” Some progressive scholars and journalists—including Essa, Friedrich, Naik, and Truschke—argue that it is important to continue poking holes in the idea that Hinduphobia is a real phenomenon; others, like Sippy, wonder if that “ship has sailed.” “Strategically, I don’t know if it serves us to say, ‘Hinduphobia isn’t real,’” Sippy said, noting that critics might instead benefit from clarifying “what is not Hinduphobia . . . it is definitely not the recognition of caste discrimination, or the criticism of India’s treatment of Muslims.” The question of which strategy to invest in is especially pressing given that anti-Hindutva groups are at a steep material disadvantage—HfHR’s staff, for example, is half the size of the HAF’s.

Left-wing Jewish groups like JVP and IfNotNow have sought to navigate a similarly asymmetrical landscape—and combat a similar politics of pervasive anxiety—in part by disentangling Jewish identity from Zionism, insisting in the process that criticism of Israel need not threaten Jews. Now, anti-Hindutva groups like HfHR, Sadhana, and Students Against Hindutva Ideology are experimenting with reclaiming Hinduism itself from the Hindu right. HfHR hosts events that reinterpret Hindu tradition through a liberationist lens, such as “Holi against Hindutva,” a gathering that transformed the Hindu “festival of colors” into a day of political education. The group has also retrieved an expansive pantheon of Hindu deities traditionally patronized by queer communities, Dalits, women, and others excluded by the Hindutva project. HfHR has even reinterpreted the idea of Ram rajya, or Ram’s kingdom—a mythological time of divine justice, which the Hindu right has long used to denote the coming of a purely Hindu India—to symbolize something similar to Martin Luther King Jr.’s “beloved community,” a vision of a just, anti-racist society. Hindutva organizations may have positioned themselves as the representatives of the US Hindu diaspora, but Mandalaparthy said that groups like HfHR are contesting for space: “We have intentionally tried to go wherever the Hindu right groups are, so that there’s not just one Hindu voice.”

Support for this article was provided by a grant from the Puffin Foundation.

This piece has been updated to reflect that the advocacy organization Indian American Muslim Council was one of the parties sued by the Hindu American Foundation in 2021.

Aparna Gopalan is news editor at Jewish Currents.