Revaluing the Strike

Rather than viewing strikes as a last-resort bargaining tactic, the labor movement must embrace them as engines of political transformation.

United Auto Workers President Shawn Fain addresses striking auto workers as Joe Biden looks on at a picket line in Michigan on September 26th.

In the end, the strike of the summer never materialized. The 340,000 UPS workers represented by the International Brotherhood of Teamsters could have eclipsed even the star-studded Hollywood picket lines and the presidentially sanctioned United Auto Workers (UAW) strike if they had walked off the job, bringing an increasingly delivery-dependent American economy to a grinding halt. This prospect seemed all but inevitable when negotiations between the Teamsters and UPS broke down in early July—to the elation of labor radicals and the despair of just about everyone else, including the Biden White House and its allies. (Vox fretted that “a UPS strike would be worse than you think,” while Bloomberg speculated about the possibility that Biden might invoke rarely utilized presidential powers to crush the hypothetical strike.) But in a dramatic reversal, Teamsters leadership assented to a tentative agreement just a few weeks later, with days to go before the union’s August 1st strike deadline. Members overwhelmingly ratified the contract in late August, and UPS workers remained on the job.

Centrist and left-liberal commentators alike rejoiced at the outcome. Politico praised the deal for “sparing Biden another economic disaster.” CNN expressed relief that “the threat of a crippling strike” had lifted. Biden himself congratulated the company and the union for negotiating “a better deal for workers that will also add to our economic momentum.” And writing for MSNBC, the labor journalist Hamilton Nolan celebrated the Teamsters’ “spectacular nonstrike” as “a testament to the ideal of labor peace through labor strength.” “A union’s ideal victory comes not by winning a hard strike, but by pushing a company into backing down without ever having to strike at all,” Nolan wrote. He is not the only one to treat the episode as proof that one of the benefits of robust union power is an economy less frequently disrupted by strikes. For newly minted Teamsters president Sean O’Brien, too, “a strong settlement reached without a strike was [the] preferred outcome,” according to labor sociologist Barry Eidlin. “The rank-and-file Teamsters I have spoken to over the past year understood this,” Eidlin wrote in Jacobin after the tentative agreement was reached, “and none were expecting a strike, even after negotiations broke down.”

O’Brien is hardly an outlier in the American labor movement. “This is not a strike-happy union,” insisted SAG-AFTRA lead negotiator Duncan Crabtree-Ireland earlier this year. “This is a union that views strikes as a last resort but we’re not afraid to do them when that is what it takes to make sure our members receive a fair contract.” UAW leaders took a similar line in the run-up to that union’s strike deadline in its contract fight with the Big Three auto manufacturers. “Our goal is not to strike. Our goal is to bargain a fair contract,” said UAW’s president Shawn Fain, and as contract negotiations wore on without resolution, union organizers at auto plants around the country could be seen sporting buttons that read “I don’t want to strike, but I will.” This rhetoric signals to workers that union leaders understand the risk of economic hardship entailed in the decision to go on strike; it is also calculated to maintain the goodwill of consumers and politicians likely to be frustrated by the consequences of a protracted work stoppage. But the Teamsters’ recent choices suggest this is not just talk. Even after building an extremely credible strike threat—credible enough to entice UPS back to the bargaining table as the deadline grew near—the union’s leaders ultimately preferred the certainty of a good deal without a strike over the chancier possibility of a great deal won on the picket line.

In the labor press, much of the debate about the Teamsters contract has revolved around this trade-off. How good was the deal, exactly, and how much better could it have been if UPS workers had gone on strike? It’s hard to be sure. There were real wins: The new contract provides raises for all UPS union workers; restricts the company’s ability to mandate overtime work; guarantees air conditioning in new vehicles and a program to retrofit older trucks with fans and air induction vents; and moves to close the gap in wages and benefits between UPS’s full-time and part-time workers, including the creation of 7,500 new full-time union positions and the elimination of a classification system introduced in the last contract that kept some workers paid at part-time rates no matter how many hours they worked in reality. On the other hand, the new floor for part-time workers’ wages, set at $21 per hour, lags well behind the $25 per hour demanded by the reform caucus Teamsters for a Democratic Union (which enjoys particular strength among part-timers, whose interests O’Brien’s predecessor James P. Hoffa habitually disregarded). Furthermore, coming as it did amidst an apocalyptically hot summer, the fact that the agreement guarantees air conditioning only in new vehicles, and only starting in 2024, has drawn the ire of drivers, who are skeptical that fans and induction vents will really be able to keep them cool during the extreme temperatures poised to become our new normal. In addition to concerns about wins left on the table, there is also the question of optics. Allowing an employer to avert a strike can appear cowardly to workers dissatisfied with the deal: If UPS was that scared when all we had done was threaten a strike, the argument goes, imagine what we could have won if the strike actually got underway.

Even those who have questioned the Teamsters leadership’s decision to avert a strike have rarely challenged their underlying logic—that strikes are, at best, a necessary evil, a tool whose sole purpose is to extract better collective bargaining agreements from employers.

These critiques deserve to be taken seriously, and O’Brien will have to grapple with the limitations they highlight during the next round of UPS contract negotiations. But even those who have questioned O’Brien’s decision to avert a strike have rarely challenged his underlying logic—that strikes are, at best, a necessary evil, a tool whose sole purpose is to extract better collective bargaining agreements from employers. Yet historically, strikes have not simply been instruments for negotiating better compensation packages. Rather, in periods of militancy, striking has served as a way to refuse managers’ absolute authority over the labor process, enabling unions to serve as engines of political transformation in the workplace. In recent months, reformers like O’Brien and Fain have invoked this latter vision of what unions are for. “It’s the Teamsters who actually run this company,” O’Brien said in July. UAW’s Fain has expressed a similar sentiment, recently declaring that his union was fighting for a world where “no one forces others to perform endless, backbreaking work just to feed their families or put a roof over their heads.”

Despite their ambitious understanding of unionism, however, these leaders—like many in the reform movements that helped elect them—still retain an instrumental view of the union’s most powerful tool, treating strikes as a last-resort negotiating tactic rather than as the creation of a space, however evanescent, where the bosses cannot compel work. But strikes challenge capitalists’ unilateral decision-making power—their authority to decide the who, what, when, and where of work. In doing so, they not only allow workers to confront existing structures of governance in the workplace, but also call into question the balance of class power in society as a whole. To create a world where no one is forced to do “backbreaking work,” and to realize the vision of workplace democracy at the heart of today’s union reform movement, labor activists must reclaim this inherently political understanding of striking—not as a necessary evil but as a positive good.

Union workers in the United States used to strike for all kinds of reasons. They struck to improve their pay and hours and to redress on-the-job safety concerns—not through protracted bargaining sessions, but through concessions that the boss granted in order to end the strike. They struck to make bosses recognize their unions, before there was any formal legal infrastructure for certifying union elections, and to demand legislative change, as in the Eight-Hour Day movement of the late 19th century. They struck in opposition to technological and organizational “improvements” imposed by management that threatened to kill jobs or degrade the condition of labor, as in the famous 1911 strike at the federal arsenal in Watertown, Massachusetts—which led to congressional hearings on Frederick Winslow Taylor’s dehumanizing “scientific management” system—or the 1913 strike of silk workers in Paterson, New Jersey, which pushed back against new technology that required weavers to work on multiple looms simultaneously. Most fundamentally, workers struck in order to create a labor movement: to politicize, energize, and empower the nascent industrial working class. “Doubtless even more important than the specific objects realized by strikes, has been the permanent impression produced upon the minds and the temper of both employers and employed,” wrote Francis Amasa Walker, inaugural president of the American Economic Association, in his 1887 textbook Political Economy. “The men have acquired confidence in themselves and trust in each other; the masters have been taught respect for their men, and a reasonable fear of them.”

In the decades after Walker’s observation, the masters’ fear of strikes intensified feverishly. In the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, bosses struggled with mixed results to suppress labor unrest with newfangled management schemes, and with military and paramilitary violence. The counterinsurgency helped to break the power of craft unions, which were limited to workers in a single trade—but a new generation of even more strike-ready “industrial unions,” which sought to organize all the workers in a given sector, rose up in their place. Finally, in the depths of the Great Depression, and threatened by a wave of successful strikes that swept the nation in 1934, the capitalist state found itself willing to consider a new approach: creating a legal right to strike—for certain workers, in certain circumstances—in an effort “to diminish the causes of labor disputes burdening or obstructing interstate and foreign commerce,” per the text of the 1935 National Labor Relations Act (NLRA). The passage of the act was met with bitter opposition from many corporate executives—and, as they feared, its immediate consequence was to invigorate new labor organizing. But as the historian Nate Holdren points out in his critical study of the NLRA, there is no reason to assume that capitalists are infallible in assessing where their best interest lies, especially in situations where long-term benefit requires short-term sacrifice.

In the case of the NLRA, capitalists sacrificed the ability to use state or private violence to crush most kinds of strikes, but in return, they obtained the codification of a tightly circumscribed conception of what striking was: a necessary evil, only legitimate in the context of ongoing collective bargaining. The act states that union activities deserve state protection insofar as they are “fundamental to the friendly adjustment of industrial disputes arising out of differences as to wages, hours, or other working conditions.” While asserting a right to strike, then, the framers of the NLRA envisioned the incorporation of striking into a “friendly” pattern of collaboration between employers and unions, as a mechanism for keeping greedy employers in check and securing collective bargaining agreements sufficiently generous to avert more drastic forms of unrest. Labor peace through labor strength, in Nolan’s words. As the legal scholar Diana Reddy argues, “with the enactment of the NLRA, the strike became lawful as a bargaining tactic of last resort, not as a political right, necessary for co-determination.”

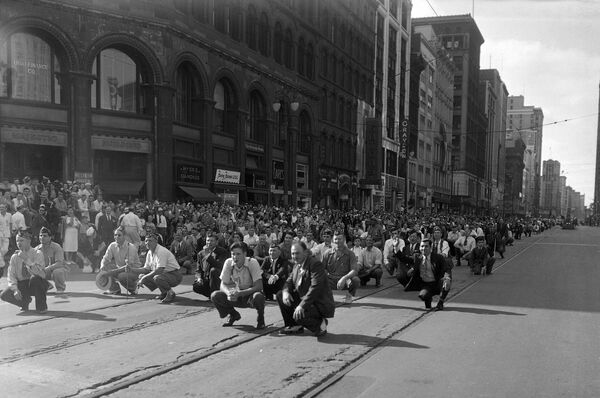

CIO members stage a sit-down strike during a Labor Day parade in Detroit, Michican, date unknown.

Even after the NLRA, workers did not immediately abandon the older conception of the strike as a political act. In 1945 and 1946, workers responded to the end of World War II with a massive surge of strike activity. These work stoppages, in which some 4.3 million people participated, were animated not merely by the desire to reach more favorable collective bargaining agreements with specific employers, but by the sense that the shape of the postwar economic order was up for grabs. Not to say that pay was unimportant: The prospect of the end of wartime price controls raised the specter of rapid price hikes, while industrial workers had for years largely forsworn wage increases for the sake of the war effort. But workers were disturbed as well by a more diffuse sense that management was going on the offensive: imposing production line speedups and implementing new labor-saving (or job-killing) technologies developed during the war, as well as beating the right-to-work drum with renewed zealotry (taking advantage of the demise of the National War Labor Board, which required workers at unionized workplaces to pay union dues). There were general strikes in Lancaster, Pennsylvania; Stamford, Connecticut; Rochester, New York; and Oakland, California. By their very nature, these general strikes exceeded the confines of individual contract fights. In Oakland, 100,000 workers in 142 unions walked off the job to protest the city’s department stores’ ongoing union-busting. In Stamford, incited by the use of state police to crush a picket line at a lock-making factory, the strikers’ placards read: “We Will Not Go Back to the Old Days.” It was, in the words of the historian Philip J. Wolman, “a rebellion,” with strikes being deployed in service of an expansive working-class political project.

Faced with such unrest, capitalists were eager to restrict the scope of legitimate striking even more explicitly—to more rigidly define the strike as a last-ditch tactic in contract disputes or a form of protest against employer lawbreaking. They achieved this by passing the infamous Taft-Hartley Act of 1947, which amended the NLRA with a rash of new pro-management provisions. In labor circles, the act is often remembered as a counter-revolutionary overthrow of New Deal labor law reform. But to some extent it can also be seen as a clarification of what was always implicit in the NLRA: a distinction between good unionism, which sought to negotiate fair collective bargaining agreements about bread-and-butter issues, and bad unionism, which saw itself as the nucleus of a more radical democratization of economic life. Under Taft-Hartley, Communists were banned from union leadership, and states were empowered to enact right-to-work laws that made it the prerogative of each individual worker to decide whether membership in their workplace’s union was in their private interest.

Most significantly, Taft-Hartley dramatically limited the right to strike. Among many other restrictions, the act required unions to give 80 days’ notice before striking to obtain a new collective bargaining agreement, and outlawed “wildcat strikes” undertaken under unexpired contracts and without the authorization of union leadership. Unions were also forbidden to strike on behalf of a “political” cause or in solidarity with another striking union. Moreover, the law prohibited strikes by federal employees altogether, since their industrial activity was thought always to be troublingly “political.” Indeed, following Taft-Hartley, federal labor law came to recognize only two legally protected categories of strikes: so-called “economic” strikes, which seek “to obtain from the employer some economic concession such as higher wages, shorter hours, or better working conditions,” and strikes over legally proscribed “unfair labor practices.” Employers could now legally fire workers who struck for any other reason. Of course, that was true before the NLRA was enacted in the first place, but Taft-Hartley cemented a hierarchy between different kinds of strikes that has led, over time, to the virtual eradication of legally unsanctioned strike activity, without any compensatory increase in legally protected striking. Following the passage of the act, the rate and magnitude of striking in the US began a long-term decline that continues to the present day.

Crucially, this decline was not just a spontaneous reaction to the new legal landscape; it was actively enforced by a generation of union leaders who, as a condition of their ascent to power, agreed to implement the purges of Communist organizers prescribed by Taft-Hartley and the Red Scare state. These leaders were committed to what scholars call “business unionism,” a model of union leadership patterned on corporate management that emphasized the financial health and institutional durability of the union. Sometimes called “pure-and-simple unionism” by its proponents, business unionism focused on securing steady improvements in members’ wages (and, especially after World War II, in their benefits) while eschewing a more ambitious vision of class struggle and marginalizing the use of strikes. In the early Cold War era, business unionists increasingly agreed to long-term collective bargaining agreements in which they committed not to strike for the duration of the contract. While in the late 1940s, union members had to at least prepare for the possibility of a strike each year when annual contracts came up for renewal, by the ’50s contract durations had begun to increase and it had become common for unions to go years without an official strike. As a result, the officially sanctioned strikes that did transpire during the ’50s meant something different than the strikes of prior decades, becoming signs that collective bargaining was not working as it should; that there was friction in what was supposed to be a frictionless machine.

As Mario Tronti, the late Italian intellectual and politician whose work was a major inspiration to left-wing American labor activists in the ’60s and ’70s, has argued, unions that do not strike serve merely to rearticulate “capital’s own needs” as “working-class demands,” negotiating the conditions for the smooth reproduction of the labor power with which capitalists generate surplus value. The strike, on the other hand, entails “a refusal of capital’s command, its role as organizer of production.” No wonder, then, that those union leaders who were willing to concede the political supremacy of capital in exchange for the redistribution of a greater share of profits were so uncomfortable with striking. Striking was a strategy of “refusal,” but business unionism relied on acquiescence—on workers doing what they were told, by both management and their union leaders.

The strike entails “a refusal of capital’s command, its role as organizer of production.”

On its own terms, business unionism worked—for a time. For much of the 1950s, American unions consistently scored better wages and benefits for most of their members. Contemporaries typically understood this success as proof that collective bargaining really was a win-win for workers and employers. But in reality, the hegemony of business unionism was dependent in material terms on the postwar economic boom, the so-called “Golden Age of Capitalism.” When the money was flowing, it made sense for companies to divert some of it to irrigate their workers’ goodwill—to purchase labor peace with raises, pensions, and health care benefits. On the whole, however, union leaders drastically overestimated the extent to which their collective bargaining partners had actually accepted the legitimacy of unionism as a political principle. This was a catastrophic miscalculation. When profits dried up, beginning at the end of the ’50s and accelerating in the late ’60s, corporate management launched a veritable blitzkrieg on unions and union workers. The number of unfair labor practices and illegal discharges spiked abruptly in the ’60s (unconstrained by the toothless National Labor Relations Board), at the same time that employers imposed increasingly aggressive production speedups and put new automation technology into operation.

Radical activists and intellectuals tried to resist these developments. In preceding decades, the wildcat strike had become the rank-and-file’s most important tool of protest against the new status quo, “the ever-present reminder of what the American workers think of the economic system under which they live,” as Detroit-based radical organizers and theorists C.L.R. James and Grace Lee Boggs wrote in 1958. And amid an employer offensive that business unionists were poorly equipped to resist, workers’ frustrations boiled over into an unprecedented wave of wildcat strikes in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Black workers, for example, struck against many of the largest unions’ recalcitrant accommodation of racial discrimination in hiring and job assignments, while rank-and-file movements in a variety of public-sector unions produced strikes in defiance of state and federal law. The push for union militancy and the push for union democracy were thus united by their embrace of the strike.

While such rank-and-file pressure pushed some business unionists to embrace a more militant posture—founding UAW president Walter Reuther, for example, gave at least verbal support to radicals’ positions on anti-racism and other issues—others, including Reuther’s successors at UAW, helped bosses to suppress the revolt. In the end, business unionism maintained its grip on the American labor movement, in what proved to be a pyrrhic victory. After the ’70s, the productivity improvements that employers won through speed-ups and new technology did not translate to higher wages but to fewer jobs, creating a climate of fear that, alongside the Reagan administration’s semi-official anathematization of unionism, laid the groundwork for the decertification campaigns and profligate union-busting of the ’80s and ’90s. Meanwhile, negotiators across the American labor movement agreed to round after round of concessions, in keeping with the business-unionist belief that workers’ best interest ultimately lay in juicing corporate profits.

Union reformers have been working to dig us out of this hole for decades, and recently it has felt like the tide might be starting to turn. In the spirit of the wildcat strikes of the ’60s and ’70s, the recent push to reinvigorate the labor movement has gone hand in hand with both the struggle for union democracy and a revaluation of the strike. One of the most important early skirmishes in this campaign was, fittingly enough, the Teamsters’ 1997 strike at UPS, organized by a leadership team backed by Teamsters for a Democratic Union (TDU). The caucus emerged out of a ’70s-era reform group whose slogan summed up rank-and-file activists’ frustrations: “READY TO STRIKE.” After two decades of waiting, they finally got a chance to prove it. Even as a tool in contract bargaining, the 1997 strike was successful, winning raises for part-time workers and restrictions on subcontracting. However, it did more than just facilitate a new contract; it laid the groundwork for the further growth of the reform movement within the Teamsters. Although James P. Hoffa, the son of legendarily autocratic longtime Teamsters leader Jimmy Hoffa, subsequently wrested back control of the union, the 1997 strike was a crucial episode in the growth of TDU, activating many of the organizers whose efforts led to the election of Sean O’Brien in November 2021. “For 12 years I was pretty much apathetic, quiet, I didn’t go to union meetings,” future TDU executive board member Ken Reiman later recalled. “Being on the picket line made me a union activist.”

The recent push to reinvigorate the labor movement has gone hand in hand with the struggle for union democracy—and a revaluation of the strike.

A more recent inflection point for the union reform movement came with the wave of teachers’ union strikes that began with a 2012 work stoppage in Chicago and swept across Republican-controlled states in 2018. In many cases, these strikes were illegal; many legislatures ban state employees from striking, in concurrence with the Taft-Hartley logic that public worker strikes are inherently political and therefore illegitimate. For decades, union leaders’ acquiescence to these restrictions had left the public-sector labor movement moribund even as state employees accounted for an ever-increasing fraction of the United States’ unionized workforce. While the recent teachers’ strikes were often galvanized by the desire for higher pay, more school funding, and other tangible “bread-and-butter” issues, striking teachers, like their predecessors in the upheaval of early American industrialization and the rank-and-file revolt of the ’60s and ’70s, were also seeking to build a new kind of labor movement—militant, empowered, fearless. This labor movement would embrace the kinds of battles long stigmatized by business unionists as “political,” combatting austerity and underfunding, and seeking without apology to influence local, state, and even federal policy. Today’s teachers’ union movement, according to United Teachers Los Angeles president Alex Caputo-Pearl, has rediscovered “the strike not only as the last resort, but as something you do to build a social movement.” One 2018 rank-and-file strike organizer in Charleston, West Virginia, testified to the labor scholar Eric Blanc about the transformative experience of going out on strike: “I’m excited, I’m thrilled, I feel like my life won’t ever be the same again.”

Strikes change people. They allow workers to experience, at least temporarily, a total overturning of the normal order of the workplace, a space unburdened by the countless ordinary coercions built into the structure of the capitalist labor process. On the picket line everything seems possible. This experience of collective freedom breaks through the resignation to necessity enjoined, in different ways, by both union bureaucrats and corporate bosses. A plausible strike threat, of the sort that the Teamsters built during their negotiations with UPS this summer, might be as good as the real thing when it comes to obtaining wins at the bargaining table. But it is no substitute for this more intimate experience of throwing off, even if just briefly, the despotism of capital. “There’s just a mentality in this company,” explained UPS driver and TDU board member Greg Kerwood to In These Times. “It’s something that, as a UPS employee, you find yourself struggling to describe to anyone who hasn’t worked there . . . That’s part of the reason that some folks, including myself, thought it was an absolute necessity that we strike this company, because it’s all about power.” The habitus of disempowerment that the authoritarian structure of the capitalist workplace inflicts, even on many union workers, is not something that a collective bargaining agreement can obviate. Individual workers must shake it off for themselves, and there is no better way to do so than through the collective act of refusal represented by a strike.

The point of reconceptualizing striking as a positive good rather than a necessary evil is not to suggest that union organizers can simply ignore tactical considerations such as timing, member enthusiasm, financial resources, and the possibility of managerial retaliation. But rather than seeing these challenges as a reason not to strike, unions can address them by experimenting with the form of the strike itself, as the UAW is demonstrating with its ongoing action against the Big Three automakers. Earlier this year, the UAW became the setting for one of the most dramatic success stories of the contemporary union democracy movement when reformer Shawn Fain won its presidency, unseating a management-friendly regime whose decades-long dominance had kept the union’s leaders rich while rank-and-file members fell further and further behind. Like O’Brien’s Teamsters, Fain’s new-look UAW has signaled from the beginning of its tenure that it is not afraid to strike even its biggest employers, despite continued rhetorical fealty to the “necessary evil” conception of striking. Now Fain, unlike O’Brien, has actually taken the plunge. His leadership team has designed an innovative strike strategy, which they’re calling the “stand-up strike” to hearken back to the 1936 Flint, Michigan, sit-down strike that helped to forge UAW—a nod to the ability of strikes not merely to win stronger contracts but to create a more powerful and militant labor movement. The stand-up strike builds over time: Only one plant at each of the Big Three walked out on the first day of the strike, 38 more joined them one week in, and still more might go dark as the strike continues. Part of the consideration is purely tactical. If all 146,000 UAW workers at the Big Three went on strike simultaneously, they would rapidly deplete even UAW’s formidable strike-benefits fund. The stand-up approach also creates a mechanism for escalation, something that can be hard to come by in a conventional strike.

The greatest value of the stand-up strike lies in the way that it transforms the factory floor into a battleground for those workers who are not yet on strike—or perhaps more accurately, the way that it helps to reveal the factory floor as the battleground it was all along.

But the greatest value of the stand-up strike, as its first two weeks have shown, lies in the way that it transforms the factory floor into a battleground for those workers who are not yet on strike—or perhaps more accurately, the way that it helps to reveal the factory floor as the battleground it was all along. “There’s a million ways you can stand up for the membership and stand up for yourselves” while still at work, Fain said last week. UAW organizers have instructed workers at plants still in operation to work to rule, which means refusing to do any work that they are not explicitly mandated to perform. As Labor Notes reports, workers at plants across the country have refused voluntary overtime, to the great consternation of their managers. In turn, workers and their shop stewards are scrutinizing their frustrated bosses closely and filing unfair labor practice complaints at the first sign of indiscretion—changing voluntary overtime to mandatory without adequate notice, for instance “One very positive thing that can come out of this strike and out of refusing overtime,” reports Tennessee GM worker Kenneth Larew, “is it will ignite discussion on the floor that will help teach new people that ‘union’ and ‘solidarity’ are actions, not words.”

The outstanding question right now is how long UAW will be able to sustain this level of politicization at the plants that remain active—and how many workers, ultimately, will have the chance to actually walk off the job before UAW reaches new agreements with the Big Three. Without rapid escalation and ongoing shop-floor activism, the form of the stand-up strike risks reinforcing the “necessary evil” conception, especially given top leadership’s genuflection to that view even under the Fain administration. Indeed, there are real limits on the new leadership’s ability to openly champion striking as a positive good, especially given how many UAW locals remain under the control of the old business-unionist regime despite Fain’s presidential victory (which came by a razor-thin margin). But so far the reformers have largely succeeded in walking this strategic and rhetorical tightrope: The strike they’ve designed has appealed to those members and staffers who believe that striking should be kept to the minimum degree necessary, while nonetheless opening up new modes of everyday worker resistance that have the potential to seed more radical forms of consciousness and collective action. If the stand-up strike reacquaints rank-and-file autoworkers with their ability to confront managerial power on their own initiative—weaving creative, bottom-up resistance into the fabric of everyday union life—it will help ensure that militancy remains the animating principle of this new era for UAW, not just an instrument put back into the toolbox when negotiations conclude.

“During the strike,” Mario Tronti wrote, “the working class confronts its own labor as capital, as a hostile force, as an enemy.” While its ultimate outcome remains uncertain, UAW’s stand-up strike has already shown that strikes have the power to produce this experience even for workers who are not at that moment on the picket line themselves. That is no small victory, because the tragedy of every strike—for now—is that it ends. Work returns. The question is how to retain, after the return of work, the ultimate horizon made visible by the strike: the substitution of workers’ own will for the will of capitalists in the governance of the labor process. Any union that wishes to fully honor this democratic aspiration must understand any “Yes” it offers to an employer at the bargaining table as ephemeral, a temporary departure from its underlying “No” to the tyranny of capital—the “No” of the strike.

Erik Baker is an American historian, an associate editor at The Drift, and a former UAW staff organizer.