What Happened to IfNotNow?

The close of the Trump era finds the millennial anti-occupation group at a crossroads.

ONE FRIDAY AFTERNOON in June 2019, the anti-Israeli-occupation group IfNotNow sent its roughly 2,000 members an unusually candid email. “First and foremost: we owe you all, the leaders and members of IfNotNow, an apology,” it began. Part strategy document, part confessional, the email—signed by IfNotNow’s full-time staff—responded to discontent that had been brewing for months. IfNotNow had become too hierarchical, many members said, leaving local chapters unsupported while paid national staff pursued projects in which the rank-and-file had little say. The staff email committed the group to a process of teshuva, or repentance, borrowing a Jewish religious concept that requires an offending party to repair, to the degree possible, the damage they have done. But for many disgruntled IfNotNow members, it was too late to fix an organization that had veered off course. Nearly two years later, the group remains in the throes of an identity crisis.

Founded in 2014 by young Jews who opposed American Jewish institutions’ support for Israel’s invasion of Gaza that summer, IfNotNow has become one of the best-known Jewish organizations opposing the Israeli occupation of Palestine. Its early, rapid growth—from 13 trained members in fall 2015 to over 1,300 two years later—enabled high-profile protests and national media coverage. In confrontational actions against establishment Jewish groups, from local federations to “pro-Israel” politicians to programs like Birthright Israel, IfNotNow forced debate on once-marginal policy ideas—like imposing conditions on American aid to Israel—that are gaining support among progressive politicians. It also created a community that was unabashedly Jewish, progressive, and anti-occupation.

Alongside these forceful stances, however, the group also decided early on to prioritize the cultivation of a big tent over the adoption of polarizing policy positions. Hoping to bring together liberal Zionists, anti-Zionists, and those poised somewhere in between, the group declined to take positions on questions of binational statehood, the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement, or the idea of Zionism itself. But in the six years since IfNotNow’s founding, the discourse on Israel/Palestine has changed dramatically. For many Jews who came of age in the Trump era, such neutral stances seem out of step with political reality. “I’m a fucking reformist compared to these kids,” said Max Berger, a co-founder of IfNotNow who served last year as an aide to Senator Elizabeth Warren’s presidential campaign. As a result, the organization’s attempts to create a broad base of support have sometimes backfired: When IfNotNow launched an electoral arm ahead of the primary season last summer, for instance, some members derided the move as a capitulation to Democratic party politics and the Washington lobbying game. Such dissatisfactions coincided with attrition. Last winter, chapters in Pittsburgh and Austin disaffiliated from the organization. Three senior staff members—including two founders of the organization—have moved on in the past year. Even before the pandemic, new member growth had been declining, with fewer members being trained than at any time since the organization’s founding.

Last summer, the organization began questioning its own raison d’être through what it calls a “frontloading” process, in which a committee of IfNotNow members is reevaluating not only goals and tactics, but the very mission of the organization.

Last summer, the organization began questioning its own raison d’être through what it calls a “frontloading” process, in which a committee of IfNotNow members is reevaluating not only goals and tactics, but the very mission of the organization. Should Jews defer to Palestinian leadership in the anti-occupation struggle? To what extent should IfNotNow center Israel/Palestine in its work rather than the domestic fight against white supremacy? Does it even make sense to be organizing within the Jewish community instead of focusing on multiracial coalition building? The way IfNotNow answers these questions will decide the future of the organization—and whether it should exist at all.

“There’s still more work to be done,” said Berger. “Whether or not it’s still called IfNotNow is a separate question.”

AS ISRAELI AIRSTRIKES pummeled Gaza in December 2008, the “pro-Israel, pro-peace” lobbying organization J Street issued a statement condemning the assault as “counterproductive . . . damaging long-term prospects for peace and stability.” The organization—founded earlier that year by a Clinton administration policy advisor—worded its critique of Israeli military actions in the mildest possible terms, yet the response from the American Jewish political establishment was scathing: Writing in The New Republic, conservative columnist James Kirchick dismissed J Street as “politically marginal amateurs,” while even the relatively liberal rabbi Eric Yoffie, then-president of the Union for Reform Judaism, lambasted the new organization as “morally deficient . . . and also appallingly naive.” Fearing marginality, J Street tacked to the center over the following years, distancing itself from Palestinian demands while growing its influence in the Obama administration. When Israel began airstrikes against Gaza in July 2014, J Street joined the ranks of AIPAC in affirming the country’s “right to defend itself.”

J Street’s support of the 2014 attacks was particularly jarring for some members of J Street U, the organization’s college arm, which leaned further to the left than its parent group. As the airstrikes escalated into a war, several of them—including Simone Zimmerman, a recent college graduate who had been the National Student President of J Street U while a student at UC Berkeley, and Carinne Luck, who had led J Street’s field and campaigns team for several years—gathered with Jewish alumni of Occupy Wall Street, a group that included Berger, in a Brooklyn apartment to mourn both the human toll of the conflict and the demise of a vision of a just American Jewish community. On July 24th, a week after Israeli ground troops invaded Gaza, the group assembled in front of the Manhattan offices of the Conference of Presidents of Major Jewish Organizations to read the Mourner’s Kaddish for Palestinians and Israelis who had died in the conflict. They carried a sign that read “If not now, when?,” an excerpt from a saying commonly attributed to the first-century BCE rabbi Hillel the Elder: “If I am not for myself, who will be for me? And when I am only for myself, what am I? And if not now, when?”

Over the next few weeks, hundreds of people joined similar protests across the country, organizing under the hashtag #IfNotNow. They said the Mourner’s Kaddish and sang songs of peace in Hebrew. In some cases, participants publicly shared their experiences confronting the bigoted views of family members and friends. By the time Israel and Hamas announced a cease-fire at the end of the summer, the organizers of the original action believed they had tapped into a powerful current of intra-Jewish dissent that lacked a sufficient outlet. The small but active group Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) had been organizing for Palestinian rights for nearly two decades, but many of its members were older radicals estranged from mainstream Jewish communal life, making it an uncomfortable fit for young Jews raised in the establishment and often just beginning to question its politics. Seeking to draw in their own demographic, Zimmerman, Berger, and several others spent the following year developing the strategy and organizing principles of what would become IfNotNow. In the process, they confronted thorny foundational questions: How could a small but motivated group of progressive American Jews affect meaningful change in Israel/Palestine? And how could such a group grow, when many American Jews critical of Israeli occupation remained nervous about committing to Palestinian demands?

The group’s approach to these questions drew on an organizing framework developed by Berger and other former Occupy leaders, which would later become the foundation for the activist training institute Momentum, best known for incubating groups like the youth-led environmentalist group Sunrise Movement and the immigrant rights group Cosecha. The framework was inspired by Otpor, a late-1990s Serbian protest movement that grew rapidly from a small student group into a national movement that helped topple Slobodan Milošević—a success Momentum’s organizers believed could be replicated in other contexts by following certain precepts: Rather than wait for protest opportunities, it created them through targeted disruption; it set broad goals in order to capture as wide a base as possible; and, crucially, it allowed for massive growth and local chapter autonomy through the broad adoption of a core set of movement principles. Momentum called these principles “DNA”—the guiding essence of a movement that, embedded in each chapter, would allow it to rapidly broaden its scope while preserving aspects of the professionalized, outcome-oriented approach of much progressive organizing since

the 1970s.

By rallying opposition to the occupation, rather than advocating for positions more controversial in the Jewish community, like a binational state or BDS, IfNotNow aspired to formulate a message that would go beyond liberal finger-wagging at settlement construction, but still unite the broadest possible camp of American Jews.

IfNotNow’s DNA positioned the group first and foremost against the occupation. “[We were] in the place of needing to create a moral crisis around this problem,” Berger said of the team’s thinking at the time. By rallying opposition to the occupation, rather than advocating for positions more controversial in the Jewish community, like a binational state or BDS, IfNotNow aspired to formulate a message that would go beyond liberal finger-wagging at settlement construction, but still unite the broadest possible camp of American Jews. This was, in part, a strategic decision. IfNotNow’s founders understood the occupation as supported by several “pillars,” including settlers in Israel, evangelicals in the United States, and oil despots in the Gulf. The group set its sights on the pillar it saw itself as uniquely positioned to attack: the American Jewish establishment and the politicians, particularly in the Democratic Party, who used claims of Jewish support for Israel as an excuse to prop up the occupation diplomatically and militarily. “We’re not taking responsibility for ending the occupation—that’s beyond our control,” Berger said. “What we’re taking responsibility for is ending our community’s support of the occupation.” At the same time, the decision to focus on American Jewish institutions was never solely tactical. For IfNotNow, communal support for the occupation was a moral stain on all Jews; rallying against it was thus in the self-interest of American Jewry, the very soul of which was compromised by support for such a heinous crime. “What IfNotNow said is, ‘We feel this in a special kind of way because it’s being done in our name,’” said Ben Case, a former IfNotNow member. The occupation “had to end for our own sake, for Jews ourselves.”

Many IfNotNow founders were heavily involved in Conservative, Reform, and Reconstructionist Jewish organizations (the Orthodox movement, which makes up about 11% of the American Jewish population, has had little overlap with the group). By organizing the next generation of mainstream American Jewish leaders, they conjectured, they could establish a new anti-occupation consensus within the wider American Jewish community. At the same time, they hoped to create a space where all members, including those without preexisting communal ties, could embrace a Jewish identity through—rather than in spite of or apart from—their progressive values. “As someone who went to Jewish summer camp and Jewish youth group, who got to experience joyous Jewish community, connected to songs and stories and ritual, it’s been a huge loss in my life to be exiled from those communities that raised me,” said Zimmerman, who now serves as director of the US arm of the Israeli human rights group B’Tselem. “Pro-occupation and pro-apartheid politics has poisoned so much of the Jewish world today. For people who value Jewish tradition and Jewish community, there’s huge value to building youth spaces and broader communal spaces that aren’t tainted by that.”

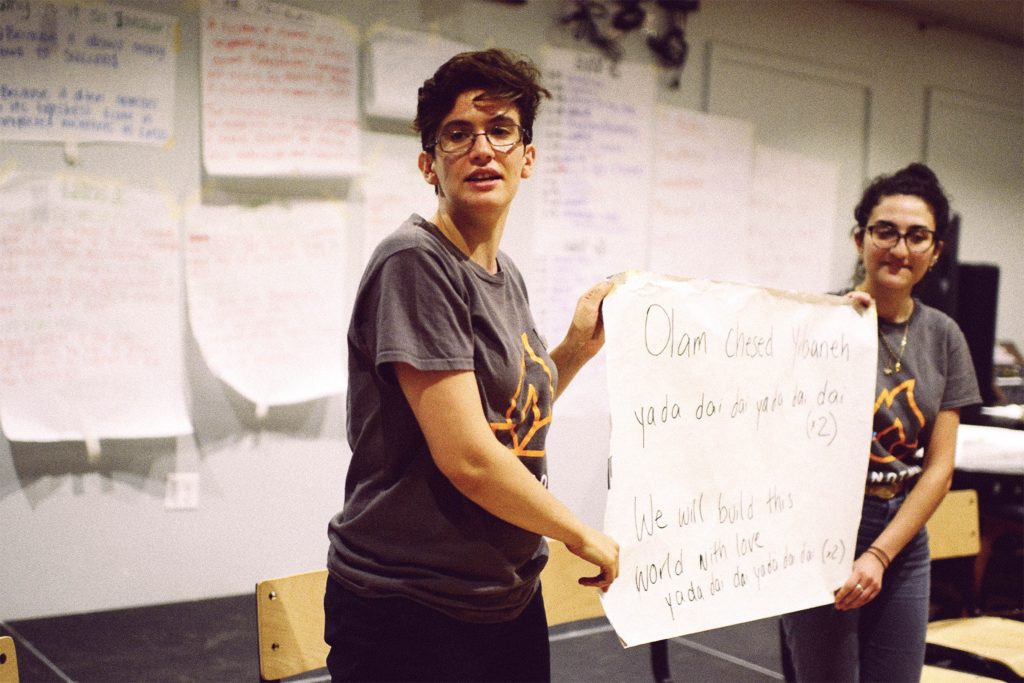

In keeping with the Momentum organizing model, new IfNotNow members were required to attend a weekend-long training session. Run by IfNotNow volunteers in a number of cities, these trainings covered organizational strategy and some background about Israel/Palestine, but their most crucial element was community-building. As part of a practice called “storytelling and resonating,” trainees were asked to tell stories about their relationship to their Jewishness and their reasons—often very personal—for joining the group; others were asked to respond with affirmations. The trainings focused unabashedly on Jewish historical trauma as a necessary site of political engagement; in visualization exercises, trainees imagined conducting a supportive exchange with an ancestor, and learned to identify the often violently jingoistic attitudes circulating in their own families as a post-traumatic response. At the end of a training, facilitators encouraged trainees to imagine the endpoint of the movement—not what the end of the occupation would mean for Palestinians, or even Israelis, but for themselves. “Visualize what it feels like to go to the local synagogue and know they support Palestinian liberation unequivocally,” one former trainee remembered being told at a Bay Area training. “What it’s going to feel like when the public perception of the Jewish community isn’t about Israel.” In interviews, some members described the process as manipulative, while others said they found it revelatory. Nearly every IfNotNow member interviewed for this story described crying at their first training.

IFNOTNOW’S GOALS AT THE OUTSET were wildly ambitious: Within five years, the organization aspired to grow to 30,000 members and end the American Jewish community’s support for the occupation. These metrics were always more aspirational than realistic. In 2016, however, a series of events drew attention to the group. First, that April, the Bernie Sanders presidential campaign announced it had hired Zimmerman—then a 25-year-old IfNotNow activist—as its Jewish outreach coordinator. When the conservative Washington Free Beacon published a Facebook post Zimmerman had written deriding Netanyahu, an outcry from the Jewish establishment led the Sanders campaign to suspend her—giving free publicity to IfNotNow in the process. But it was Donald Trump’s election that November that vaulted IfNotNow to national prominence. Shortly after Election Day, Jewish Insider reported that Trump advisor Steve Bannon was expected to attend the annual gala of the Zionist Organization of America (ZOA), a right-wing advocacy group. IfNotNow organizers saw an opportunity: Bannon was not only an architect of Trump’s racist campaign and a peddler of white nationalism at the helm of Breitbart News, he also had a history of making specifically antisemitic statements. The organization teamed up with several other progressive Jewish groups to protest the ZOA gala. Hundreds of protesters showed up; Bannon never did. For IfNotNow, this small triumph marked a new level of clarity, highlighting the connections between white supremacy, antisemitism, and Jewish communal support for the occupation. A week and a half later, the group held a “Jewish Day of Resistance” against Trump and Bannon that included protests in over 30 cities; early the next year, IfNotNow bussed hundreds of young Jews to Washington to protest the AIPAC Policy Conference, garnering extensive media attention and the full notice of American Jewish institutions. By May 2017, IfNotNow had over 1,200 trained members—a quintupling in just one year.

Over the following year, as Trump made a full-throated embrace of Benjamin Netanyahu and the Israeli right—exemplified by his administration’s announcement in December 2017 that it would move the American embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem—it became easier for IfNotNow to tie unconditional American support for Israel to a right-wing Republican agenda. The pageantry of this right-wing alliance forced many liberal Jews to reconsider their kneejerk defenses of Israeli policy. “The extent to which liberal Jews hate Trump,” Berger said, is “impossible to reconcile with how well Netanyahu and Trump get along.” This presented an opening to move beyond the tame tactics of liberal Zionist groups like J Street, which denounced Trump and Netanyahu but declined to endorse policies that would put pressure on the Israeli government.

But despite this newfound traction, growth started to level off. From May 2017 to May 2018, only about 450 additional members were trained; over the following year, fewer than 250 joined the movement. At points, the group itself seemed ambivalent about stimulating growth through member trainings: After the AIPAC protest, Case, who had founded the Pittsburgh hive (the term used for IfNotNow local chapters), said IfNotNow staff had declined to run a training in Pittsburgh, reporting that they were having trouble strengthening existing chapters amid rapid expansion. Meanwhile, the small pool of trainers who ran the training infrastructure, some of whom had been with the movement since its inception, were beginning to burn out after several years of running intense, weekend-long affairs across the country. The Trump administration was radicalizing young American Jews at such a rapid pace that IfNotNow was having trouble keeping up. Trump’s support for the annexation of West Bank settlements—an unprecedented stance for an American president—had stripped away the mythology that the occupation was a transitional period on the way to Palestinian statehood, making it easier for American Jews to see the conflict from a Palestinian perspective, said Marjorie Feld, a scholar of American Jewish history. If IfNotNow’s leaders had initially worried that centering Palestinian experiences and demands would alienate American Jews, now it was their reluctance to do so that pushed some members away. The group made it easy for new members to join without much knowledge about Israel/Palestine, but it provided few resources for those who wanted to learn more or build deeper political alliances. Gabi Kirk, a lapsed IfNotNow member, remembered wondering, “Is Palestine just a thing that gets people in the door, and then we don’t talk about it?”

“Is Palestine just a thing that gets people in the door, and then we don’t talk about it?”

In early 2020, in response to these concerns, IfNotNow hired its first director of political education, who helped to develop a new training model: One- or two-hour sessions instead of a full weekend, with a focus on the history and politics of Israel/Palestine rather than personal storytelling. But IfNotNow’s anti-annexation campaign last summer continued to sideline key elements of the Palestinian narrative of the conflict. The right of return of Palestinian exiles, for instance—a core demand of the international Palestinian liberation movement—is mentioned nowhere in IfNotNow’s public statements. The group has rarely mentioned the Nakba. And only in the last few months has it used the term “apartheid” to refer not only to what Israel/Palestine would become after annexation, but what it already is. “How do you move beyond this occupation framing when this issue is obviously much larger than the occupation?” asked Yousef Munayyer, a Palestinian American writer and the former executive director of the US Campaign for Palestinian Rights. “The only people who think the Green Line [between Israel and the Palestinian territories] still exists are American Jewish organizations.”

The organization’s “big tent” was often internally split on how to address such questions. One conflict arose in February 2019, when Rep. Ilhan Omar came under attack for tweeting that Washington’s support for Israel was “all about the Benjamins,” a comment conservatives interpreted as an antisemitic slur. After Omar apologized, IfNotNow’s leadership issued a statement expressing support for Omar while affirming that the tweet “played into an anti-Semitic trope.” In the organization’s Facebook group, many members expressed concern that a progressive organization would lend credence to a right-wing pile-on against a leading progressive politician and Muslim woman. A subsequent statement signed by three small chapters (Austin, Northeastern University, and the University of Chicago) and 15 individual members from across the movement apologized for the official IfNotNow statement, saying that it was “based on an uncharitable and incorrect reading of [Omar’s] words,” and affirming a commitment to “forging and maintaining strong relationships with those who share our goals of justice and liberty.”

Another internal conflict erupted within IfNotNow a few months later, this time over its #NotJustAFreeTrip campaign, which called on Birthright to educate participants about the occupation, offer Palestinian perspectives, and take trips to see divided Hebron—all in an attempt to provoke confrontation with the organization. Actions associated with the campaign, like walk-offs from Birthright trips and showdowns with Birthright trip leaders, earned the group a prominent feature in The New York Times. But many IfNotNow activists expressed frustration with the campaign, which had been launched in the summer of 2018 largely by staff and national leadership, and was run with minimal input from members. For some in the organization, the issue was that, up until spring 2019, IfNotNow had not called for an outright boycott of Birthright. (JVP, by contrast, had been running a “Return the Birthright” campaign for years.) “I don’t have an issue with the Birthright campaign tactics per se,” Kirk said, “but the issue is with the analysis. What is this for?” Was undermining Birthright—or any other Jewish institution—really going to help end the occupation, or was it only about making the American Jewish institutional landscape a little less shameful?

This was not the first time a progressive American Jewish organization was faced with these existential questions. “The trajectory of IfNotNow feels very familiar to me,” said Rebecca Vilkomerson, the former executive director of Jewish Voice for Peace. When JVP started in the ’90s, Vilkomerson said, the group focused its efforts on changing the institutional Jewish community’s position on Israel/Palestine from the inside, even applying to be part of San Francisco’s Jewish Community Relations Council. “It was only after many years of outright rejection of those institutions that we decided we could build our own independent Jewish organizations,” Vilkomerson said. JVP has supported BDS since 2015, and became an officially anti-Zionist organization in 2019. “We orient ourselves to being good partners to our partners”—referring to Palestinian activists—“rather than [having] good standing in the Jewish community.”

Zimmerman admits that this question of positioning is a fraught one. “People like me who grew up in institutional Jewish communities are often shaped by seeing how the establishment is reacting, and want to transform it,” she said. But IfNotNow’s leaders came to see the upheaval within the organization as a sign that it was time for a reevaluation. IfNotNow’s Birthright campaign came to a close in June, with the teshuva email to members. “We are not immune from the patterns of tunnel vision,” the staff wrote.

THE BIRTHRIGHT CAMPAIGN—with its focus on the experience of young American Jews on a free trip, rather than Palestinians on the ground in Palestine—was a breaking point for members of IfNotNow’s Austin hive. Liana Petruzzi, a leader of the chapter, said that IfNotNow felt at first like a beacon: She had grown up in a town with few Jews and felt like an outsider in other Jewish communal spaces. But she quickly became disillusioned with what she saw as the group’s sidelining of Palestinian experience. Other members she spoke with felt similarly. During her time in the organization, she said, “the biggest critique I heard was, ‘I want to learn more about the history of the conflict.’”

IfNotNow Austin eventually started its own “Palestine 101” trainings in conjunction with a local Palestinian activist group, but frustrations with national leadership continued. In January of last year, Petruzzi and the rest of IfNotNow Austin wrote an open letter to the national membership announcing their hive’s disaffiliation, citing a “top-down structure” and the fact that “the promise of decentralization contrasted with an increase in centralized decision-making.” Since disaffiliating, many of IfNotNow Austin’s members, including Petruzzi, have joined the local chapter of JVP.

Around the same time, the Pittsburgh hive arrived at the same course of action for different reasons. Case, the once-enthusiastic founder of the chapter, said that the Tree of Life shooting in 2018 called into question whether IfNowNow’s core tactic of public protests at establishment Jewish institutions was the right strategy for a community reeling from tragedy. IfNotNow members in Pittsburgh, unlike those in cities with larger Jewish populations, often had close ties with Jewish establishment organizations and figures, even those who opposed them—a situation that presented opportunities to work within the community’s structures, rather than positioning themselves on the outside: A member who worked in a local Hebrew school, for instance, could help in the shaping of curriculum. But working with local Jewish leadership would have gone against one of IfNotNow’s binding principles: no closed-door negotiations with mainstream leaders. IfNotNow Pittsburgh formally disaffiliated last February, reconstituting itself as Jews Organizing for Liberation and Transformation (JOLT). Their disaffiliation letter embraced “the vital work of building toward community safety and solidarity in Pittsburgh.” In place of protests, JOLT has emphasized both internal Jewish community-building and the deepening of ties with other marginalized communities—a project that has centrally involved, as JOLT member Hana Uman put it, reckoning with the ways in which “white Jews have aligned with white supremacy.”

The hive disaffiliations have exposed the ways that the organization’s DNA, developed only six years ago, has been eclipsed by the events of the Trump era. Like the former members of the Pittsburgh hive, many Jewish activists I spoke with said that their desire to work on domestic issues and in multiracial coalitions has broadened and intensified in the wake of last summer’s Black-led uprising; some said they believe they can have the biggest impact fighting racism in the US. “Many people I know are not focused on Israel anymore, myself included,” said Sarah Turbow, who was director of J Street U from 2014 to 2016. “I am far more concerned with how Israel affects our domestic politics than the actual Israel politics,” she said, adding that “the situation seems so far gone there, but not as far gone here.” At the same time, Jewish activists who do want to fight the occupation have increasingly adopted a more radical anticolonial framework—a tendency on display in the Austin hive. Atalia Omer, a professor of religion, conflict, and peace studies at the University of Notre Dame, said that a new generation of young American Jews, coming of age amid the Black Lives Matter movement and its critique of the racist, carceral state, is adopting an understanding of Israel/Palestine “refracted through the racial history of the US.”

“Many people I know are not focused on Israel anymore, myself included. I am far more concerned with how Israel affects our domestic politics than the actual Israel politics.”

These two shifts—toward a focus on domestic issues, on the one hand, and unapologetic Palestine solidarity work, on the other—have benefitted existing Jewish groups that work in these areas, like Bend the Arc and JVP, respectively, and have led to the creation of entirely new organizations. In many cases the people leading and joining these new fronts are alumni of IfNotNow. “I’m really proud of the ways that IfNotNow has brought folks together who’ve gone on to start new projects like [the immigrant rights group] Never Again Action or Jews Against White Nationalism,” said Emily Mayer, IfNotNow’s former political director, who left the organization in late February. “I think the Trump era has helped, in a sort of twisted way, for Jews to see themselves as a minority in this country that wants to band together with other minorities under attack to create a truly multiracial democracy.” It’s apparent that IfNotNow is in no small part responsible for the Jewish left’s movement over the last few years from the sidelines of Jewish communal life to a highly visible and growing minority within it. And yet, as these alums—armed with new organizing skills and a new understanding of their role in the Jewish community—go elsewhere, they drain IfNotNow of its energy. In this way, IfNotNow has become a victim of its own success.

AT THIS POINT, the core tenet of IfNotNow’s theory of change—that reshaping American Jewish opinion could help bring down the occupation—appears dubious at best. The American Jewish establishment, and the donor class that sets its agenda, have proven adept at maintaining a posture of openness while refusing to yield to left pressure. With annexation looming, all pretense is falling away; the Jewish National Fund, for example, is planning to begin openly purchasing land over the Green Line, after a long history of disguising its support for settlements. “The mainstream Jewish community is so, so far away from understanding why we need to end the occupation,” said IfNotNow co-founder Dani Moscovitch.

This has thrown into question the organizing philosophy upon which IfNotNow was founded. The group was originally based on a “consent theory of power,” Max Berger told me, which holds that no matter how brutal and oppressive a system may be, it can be toppled by massive resistance. But while that strategy was well-suited for the student protesters of Otpor, who made Serbia ungovernable for Milošević, it has been less suited to the demands of a couple thousand young American Jews, with or without whom the Israeli occupation can continue unimpeded. IfNotNow also borrowed tactics of nonviolent civil disobedience from the American civil rights movement, but this strategy, too, was ill-fitting: Unlike Black people in the South, American Jews are not the prime victims of the oppression they were protesting, and so images of young white Jews getting arrested outside the ADL failed to provoke mass outrage and did nothing to challenge the foundation of Israeli power in the West Bank and Gaza. “Our ability to cripple this infrastructure was limited,” Berger said.

As a result, IfNotNow has, since June of 2019, embraced a new strategy: electoral work. It lent support to efforts by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and other progressive lawmakers to condition US aid to Israel, and endorsed a slate of anti-occupation candidates, including Jamaal Bowman, who scored an upset win last June against House Foreign Affairs Committee Chair and Israel hawk Eliot Engel in a heavily Jewish New York congressional district. “There’s only so much you can do by challenging the Jewish establishment on their turf,” Moscovitch said. “There’s another way to demonstrate what leadership is, and that’s to be it.” But Mayer cautioned that the group won’t be turning into a lobbying organization, stressing that elections are only one “site to build the movement.”

Over the course of our conversations, IfNotNow founders shared a range of possible paths forward for the group: it could prioritize international antifascist movement-building; become a forceful advocate for “one person, one vote” in Israel/Palestine; or, like the Sunrise Movement, work more dedicatedly in the realm of electoral politics, with conditioning aid to Israel as a chief legislative goal. But the decision, at this point, is somewhat out of their hands. A frontloading team primarily made up of volunteers nominated by IfNotNow membership has been tasked with determining what IfNotNow’s role and purpose should be moving forward.

The first stage of the frontloading process, which began last September, focused on historical inquiry, investigating topics from the origins of Zionism to the Nakba to the development of American Jewish communal life. The next stage—which will be completed this spring—will examine gaps in the “movement ecology” that IfNotNow could fill: in other words, what it could bring to a Jewish left that doesn’t exist elsewhere, in a landscape far larger and more vibrant than it was when IfNotNot was founded. The team doesn’t know yet what the outcome of the process will look like—but they are open to the possibility that IfNotNow, at least as we know it, may cease to be. “IfNotNow as a movement has never intended to exist just for the sake of existing,” said Becky Havivi, the frontloading team’s coordinator. I asked if there was a possibility the process would end in IfNotNow disbanding. “Definitely,” she said. “It’s not the intention at the outset, but in order to do a strategic process with integrity, the possibility of closing down shop needs to be on the table.”

More than a year later, IfNotNow’s path forward is no clearer than it was when the staff sent their post-Birthright campaign teshuva email. But in the long run that may not matter: While its inward-focus ultimately limited IfNotNow’s relevance in Israel/Palestine, it also ensured that its activist cadre, forged in a crucible of identity-creation, could live on long after the group’s possible end. IfNotNow’s legacy may turn out to be the generation of young people it brought into a Jewish community built around values of solidarity and struggle rather than parochialism or fear.

A previous version of this article overstated the causal link between attrition and dissatisfaction with IfNotNow’s electoral strategy.

The previous version also referred to burnout experienced by all

trainers, rather than by those who ran the training infrastructure.

The

previous version also misstated the IfNotNow principle that forbids

closed-door negotiations with mainstream leaders and the timeframe

during which the movement began doing electoral work.

Aaron Freedman is a writer based in Brooklyn, NY.