Urgency and Compromise: Progressives Run for the World Zionist Congress

The liberal Zionist Hatikvah slate hopes to win big. But for some critics, participation in the “parliament of the Jewish people” is an unconscionable moral sacrifice.

THE WORLD ZIONIST CONGRESS (WZC)—an international parliamentary body comprised of Jews from Israel, the United States, and the rest of the diaspora—is in the final days of its weeks-long election to select US delegates. These delegates will represent US Jewry at the 38th WZC in October, where the self-described “parliament of the Jewish people,” which assembles twice a decade, will administer the disbursement of nearly $5 billion for Israel-related projects over the next five years. To participate in the contest—which is open to most adult Jews who are permanent residents of the US—voters must do two things: pay a small fee ($7.50, or $5 for those age 25 or younger), and click a button to affirm that they sign on to the Jerusalem Program, a platform of Zionist beliefs most recently amended by the congress in 2004.

Hadar Susskind gets why some people might not want to click the button. Susskind—who is coordinating the liberal Zionist Hatikvah slate’s efforts to turn out unprecedented numbers of progressive Jews to vote for them—acknowledges that the language in the Jerusalem Program makes some potential voters uncomfortable. For instance, the final principle that voters must stand by is “[s]ettling the country as an expression of practical Zionism.” Most progressive Jews are well aware that the primary “settling” effort in “practical Zionism” today is the further establishment of Jewish settlements in the occupied West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Golan Heights, in defiance of international law. Left-leaning Zionists—as well as non-Zionists and anti-Zionists—have railed against such settlements for decades. So how can these critics affirm the WZC’s platform in good conscience?

“Most people read that as a right-wing statement, right?” says Susskind. “They go, ‘Oh, my God. If I click this thing, I’m supporting annexation [of the West Bank].’ But it’s vague. It doesn’t actually say that.” In his eyes, the line could just as easily refer to development inside the UN-recognized borders of Israel. He thinks that nervous lefties should feel free to interpret it this way. “The concept of settling the land goes back to the kibbutz movement,” he says, which he sees as “very progressive.” “That’s been decades of work on [the right’s] part to own the narrative, to own the language, to own the institutions,” he says. “And that’s what we’re fighting back against.”

Alissa Wise used to believe that institutions such as the WZC could serve progressive ends, too. Though she is now a rabbi, activist, and organizer with Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP), which officially opposes Zionism, she ran for the WZC on a liberal Zionist slate a decade ago. “My thinking was along the lines of what this Hatikvah slate is doing,” she says. “I was like, ‘It’s worth a shot. Rather have our liberal voices in here than just let it go to the rightward masses.’” But now she sees the WZC as “limited at the very least and dangerous at the very most.” “The World Zionist Congress is only available and open to Jews,” she says. “It reifies the model of Jewish supremacy that dominates Israel today. What kind of change can happen through that medium?”

The struggle of Hatikvah in the WZC contest is, in many ways, the struggle of liberal Zionism everywhere today. Advocates of the ideology are attempting to remain a force within institutions increasingly dominated by the right, while alienated leftists say they cannot in good conscience participate in organizations like the WZC; for leftists, the moral dilemmas that liberal Zionists face today are emblematic of contradictions that have been present since liberal Zionism’s founding. After all, the kibbutzniks whom Susskind admires may have been egalitarian on their agricultural settlements, but there were many of them among the Jewish soldiers who spurred the Nakba—the mass expulsion of more than 700,000 Palestinians in 1948—and the kibbutzim themselves were often established on the sites of eradicated Palestinian villages. At the same time, the right, in its pursuit of a reactionary Greater Israel, derides liberal Zionists as anti-Israel or even antisemitic. Hatikvah stands wedged between these two ideological camps, making a desperate effort to prove that a compromise can still be found.

There has been no polling for the WZC election, so Hatikvah’s likelihood of success remains unclear. But there’s no denying that the slate has made a big splash in Jewish circles this year, largely due to its lineup. The slate boasts a number of well-known names from the American Jewish community, such as United Federation of Teachers (UFT) president Randi Weingarten, New Israel Fund CEO Daniel Sokatch, J Street president Jeremy Ben-Ami, and American Jewish World Service global ambassador Ruth Messinger. (Full disclosure: Jewish Currents editor-at-large Peter Beinart and contributing writer Elisheva Goldberg are both running on the Hatikvah slate, and the magazine has run paid advertisements for the slate.) Staple liberal Zionist organizations like J Street, Americans for Peace Now, and Habonim Dror North America have all endorsed the effort.

But even if Hatikvah’s bets pay off, and liberal Zionism carries the day, critics question whether the WZC actually has the power to impede Israel’s right-wing trajectory—and wonder whether participating at all legitimizes the exclusion of Palestinian voices. The question surrounding Hatikvah’s bid, then, is one faced by progressives the world over: Can you make change from within a system that does not share your values?

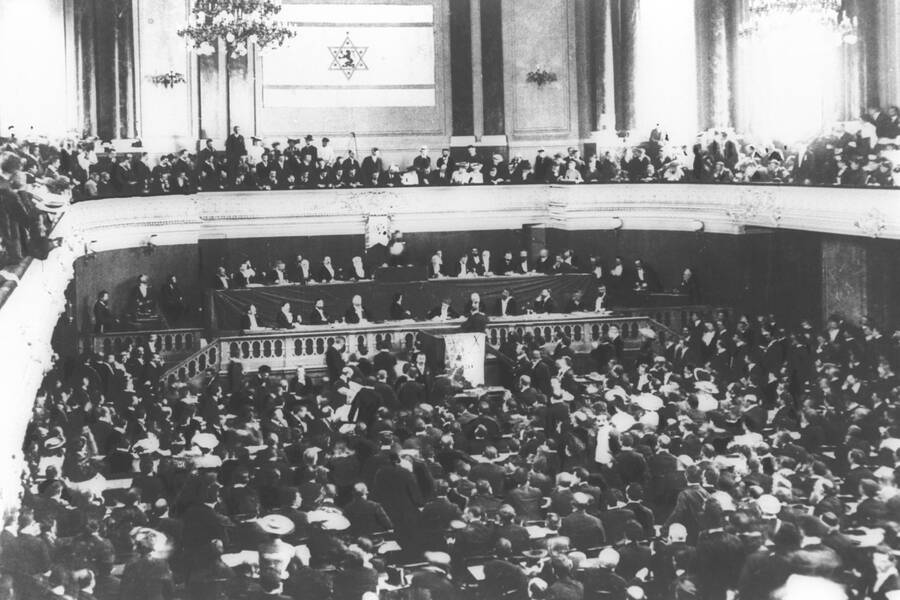

THE WZC WAS FOUNDED in 1897 by Theodor Herzl as the Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland, as the symbolic legislative authority of the Zionist Organization, which was created to determine and declare the Zionist movement’s intentions on a wide range of issues, from where they proposed to settle to what it meant to be a Zionist. The Zionist Congress met annually until 1901, then bianually until 1946—except for hiatuses during each of the world wars—and has convened every four or five years since the founding of the State of Israel. In 1960, the Zionist Congress became the World Zionist Congress, while the Zionist Organization became the World Zionist Organization (WZO). Today, the 525 seats of the WZC are allocated geographically: Israel gets 200 delegates, the US gets 152, and the rest of world Jewry gets the remaining 173. While US Jewry votes directly, and other diaspora communities generally agree on delegates through other means, Israel’s membership is determined by the party makeup of the Knesset.

The WZC’s power relies primarily on its ability to select the leadership of the WZO (now an NGO that promotes Zionist initiatives, and which has been known to funnel money into the settlement enterprise), the Jewish Agency for Israel (the office that handles Jewish immigration to Israel), and the Jewish National Fund (a public-benefit corporation that buys land in Israel/Palestine for exclusive Jewish use). Those institutions collectively control about $1 billion every year for various Zionist initiatives, from conservative causes like settlement expansion to liberal ones like funding for non-Orthodox religious denominations within Israel.

But when it comes to the big-picture policy decisions that truly shape Zionism and Israel, the WZC is a virtual nonentity. Some critics on the right mock its continued existence: “[T]he reason you probably never heard of this election until very recently is because it’s a totally meaningless organization with no real power,” Liel Leibovitz wrote in Tablet last month. But this assessment didn’t stop the right-wing Leibovitz from expressing concern that a revitalized WZC could achieve progressive change. In the same article, he wrote that the Hatikvah slate is “set to win” and must be stopped, lest Hatikvah turn the “run-down castle” that is the WZC into “a moneyed and weaponized bastion from which to attack the very thing it was supposed to defend.” The ultra-Orthodox Eretz HaKodesh slate, recognizing that its constituency is often turned off by secular Zionist institutions like the WZC, has run ads comparing participation in their elections to taking bitter medicine or running into a burning building to save a child—an unpleasant but necessary effort to prevent secularism from taking root and to protect religious education.

Hatikvah doesn’t take the openly cynical approach to the WZC that those conservative voices do, and slate members talk at length about wanting to achieve their dreams of a peaceful, Jewish, and democratic Israel that lives alongside a similarly envisioned Palestine. However, the implicit message of their pitch is still one of fear: the reactionary right is ascendant in the US and Israel, and liberal Zionists must cling to whatever power they can hold.

In the last election, a meager 56,737 votes were tallied, but officials say that this time around, more votes were cast in the first few days alone. Last time, Hatikvah drew only 3,148 votes, but they’re hoping that their increased organizing efforts and big-name slate members will give them an edge over their bloc partners—and the last congress’s largest American party—ARZA, the Zionist arm of the Reform Judaism movement, which earned 21,766 votes in the last election. From that perspective, the wind is at their backs. Yet the momentum in the Israeli government is moving in the opposite direction.

The continued rightward trajectory of Israeli politics is precisely why Hatikvah slate members believe that their voices are needed in the WZC now more than ever. “In an arena of this level of hate and divisiveness, we have to lean into hope and aspiration,” says Randi Weingarten of the UFT. “I’m not being Pollyannaish, but this is a real which-side-are-you-on moment, and I’m on the side of justice.”

Economist Mark Gold, who is also on the slate, echoes that sentiment. “There have always been differences of opinion in the Jewish community, but at no time in my adult life have those differences of opinion been set so sharply—I think there’s a lot at stake here,” he says, adding that annexation is “politically very real” and that “for moral reasons, for political reasons, for demographic reasons, this is a very dangerous thing for the democratic future of a Jewish state.” J Street’s Ben-Ami speaks in expansive terms about the importance of this election. “This election is a flashpoint in the story of Zionism as a whole,” he says.

This sense of urgency is what led to the creation of this year’s unprecedented Hatikvah coalition, which formed largely as a result last summer’s advent of the Progressive Israel Network (PIN), a coalition of groups that are enacting a desperate effort to shore up liberal Zionism in the face of both criticism from the left and overwhelming opposition and demonization from the ever-rising right.

“I think it does feel to a lot of people that we’re in a different situation than we were five or ten years ago,” says the New Israel Fund’s Sokatch. “The reveal of the Trump plan—which coincides with the series of elections [in Israel] and which is also coinciding with this rising ethnonationalist, populist, right-wing, neo-authoritarian moment—inspired the constituent parts of members of PIN to try to leverage their power in a different way.” The traditional core groups that formed Hatikvah welcomed a set of new partners like J Street and the rabbinic human rights organization T’ruah, and they hired Susskind—who had previously worked with Jewish advocacy groups like J Street and Bend the Arc—to do a campaign push.

Though there are other left-leaning slates on the ballot—and Hatikvah has historically made common cause with them on votes in the WZC—Hatikvah’s platform is the most staunchly left-wing, especially on the legal status of the West Bank: it states that the members “stand with Israelis that welcome asylum seekers” and seek “full legal and social equality for the LGBTQ community, including marriage rights,” among other declarations. Some of their most compelling arguments involve defending against potential conservative attacks on liberal gains. “Our people created the first ever office of LGBTQ equality in the WZO. [Conservatives] would certainly get rid of that,” says Susskind. “Instead of putting money into pluralistic education and sending shlichim [emissaries] of all genders and backgrounds, they would go back to having Orthodox men only, sharing right-wing views on Israel and religious issues.”

Some of the right-wing slates blatantly support the further entrenchment of the occupation and oppose a Palestinian state. The Orthodox Israel Coalition’ platform declares its intent to “[s]upport the settlement and development of Eretz Israel including the communities in Judea, Samaria, and the Golan Heights”—all areas that international law does not regard as belonging to Israel. The Zionist Organization of America’s eponymous slate urges voters to “[s]ay ‘No’ to an Iranian-Proxy Palestinian-Arab terror state!” While the Hatikvah platform demands an end to the occupation and the achievement of a two-state solution—at the top of their list of agenda items, it says that they “fiercely oppose the current policy of permanent occupation and annexation”—the WZC has no mechanism to stave off annexation, especially in the face of US and Israeli government support. Even if it wins in a landslide, Hatikvah can only declare its opposition and install institutional leaders who disapprove of it.

Some critics believe that Hatikvah is deeply misguided in thinking it can effect change from within an institution like the WZC. Writer and activist Amjad Iraqi, who is a Palestinian citizen of Israel, is among them. He says, “One of the big questions is: Can you reform—not necessarily reform, but even prod—the congress or the organization into a different direction?” Iraqi is skeptical that this is possible. Moreover, he believes that the WZC is oppressive by its very nature. It’s infuriating, he says, that the WZC gives the Jewish diaspora a say in what happens in his country, while the Palestinian diaspora has no equivalent voice. “The idea—regardless of whether it’s right-wing or left-wing Jewish slates in the congress—that they’re the ones having an influence and a say on what can be done is inherently exclusivist, inherently discriminatory, and inherently racist,” he says.

Members of the Hatikvah slate maintain that, whatever problems there might be with the WZC as an institution, progresive Jews should still participate. “There’s a million things that are wrong in Israel. There’s a million things that are wrong with the structure of the World Zionist Congress,” says Rabbi Jill Jacobs, executive director of T’ruah. “But my choices are either keep pushing really hard at building power or give up and let the other side win. Those don’t seem like very difficult choices to me.”

Hatikvah members believe that progressive Jews must participate in the WZC to prevent its full takeover by right-wing forces. When asked whether there’s a red line past which he could no longer participate in Zionist institutions like the WZC, David Dormont, political chair of J Street’s Philadelphia chapter, responded, “My answer is no.” A dozen slate members gave variations on this same answer.

“If we abandon these institutions,” Dormont says, “they’re going to be awful and really, really bad things will happen.” He cites the importance of moves like exposing covert donations to the settlement enterprise that are laundered by the WZO, something he couldn’t do if he weren’t on the inside of the WZC. “We can’t abandon the fight,” he says.

But in the eyes of Jews like JVP’s Wise, continuing to grant the WZC legitimacy means making a serious moral sacrifice. “Participating in Jewish supremacist institutions compromises our ethical and moral fibers in the Jewish community,” she says.

At the first Zionist Congress, Herzl celebrated the fact that Zionism had managed to, in his view, unite “the most modern elements of Judaism with the most conservative . . . without the need for either side to make undignified concessions or to make mental sacrifices.” Today, Hatikvah’s brand of liberal Zionism, caught in a fast-crumbling middle ground, requires a great many undignified concessions and mental sacrifices in order to enter the halls of power. Susskind recalls adopting a utilitarian mindset in order to click the button signing on to the Jerusalem Program. “I look at that and I interpret that to my beliefs,” he says. “To say, ‘Look, this is dusty old language. Signing it isn’t doing anything. It’s not putting money somewhere. It’s not voting for something.’”

But for Palestinians like Iraqi, that willingness to compromise matters, because it’s indicative of liberal Zionists’ refusal to confront the contradictions inherent in their ideology—a confrontation that he believes is necessary in order for people who care about Palestinian rights to regroup and make real change. “Liberal Zionism was still the original sinner for Palestinians on the ground,” he says. “The friction within that ideological framework of trying to ensure some privileges to one particular ethnic-racial-religious group and trying to create the system—or pretense—of democracy will always be a friction. And that friction means inherently that liberal Zionism is not democratic.”

A previous version of this story misstated the numerical breakdown of WZC delegates, based on out-of-date information offered by the WZO.

Abraham Josephine Riesman is the author of Ringmaster: Vince McMahon and the Unmaking of America and True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee. She is a freelance journalist and a board member of Jewish Currents.