There’s No Such Thing as “Free Speech”

Writer P.E. Moskowitz discusses how the left can take back the “technology” of free speech.

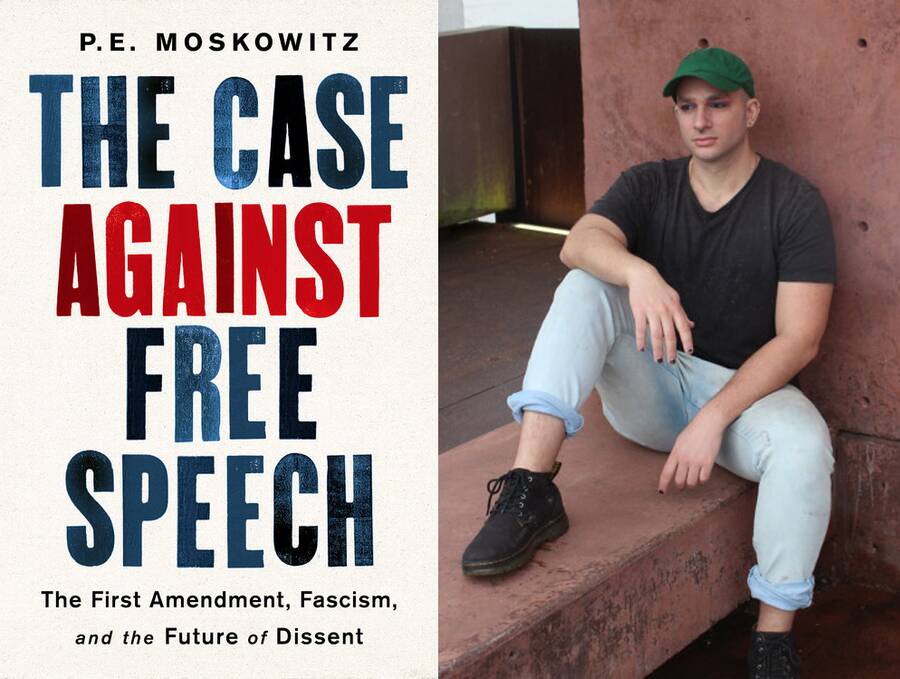

In their first book, How to Kill A City: Gentrification, Inequality, and the Fight for the Neighborhood, P.E. Moskowitz—journalist, writer, and co-founder of the Study Hall media collaborative—looked at the corporate and political forces of gentrification that are causing housing crises throughout the country. The book was widely praised for its integration of investigation with firsthand accounts of the human impact of gentrification. Moskowitz accomplishes a similar feat in their new book, The Case Against Free Speech: The First Amendment, Fascism, and the Future of Dissent. Through discussions with people on the front lines of the national debate about so-called “free speech” in places like Charlottesville and Middlebury College, Moskowitz reveals what this debate obscures and whom it serves. These accounts—alongside tenacious reporting on the history of the First Amendment, political dissent, and the ACLU—also provide us with a jumping-off point for a new, leftist framework for understanding free speech.

Sophia Steinert-Evoy: In the introduction to The Case Against Free Speech, you write that the book is exploratory, rather than prescriptive. What inspired this exploration?

P.E. Moskowitz: I’ve had trouble answering that question for myself! I’m realizing that both of my books have come from the same place, of being someone who reads a lot of mainstream media coverage and sees the insufficiency of the main national dialogue. With the first book, it was like: everyone is talking about gentrification, but really superficially. In the same way, this book came out of seeing all of these op-eds saying, “Oh, these college students are stupid” or, “If we have a trigger warning in a classroom, then free speech will end in the United States,” or whatever, and then seeing all the Twitter dunking on those people, and feeling that no one was actually talking about what was happening in a deep way.

SSE: The book’s title is obviously provocative. But you clarify that even though the right is in favor of “free speech,” and lately couches a lot of political ideas in terms of that concept, that doesn’t mean that it should be the left’s position to be against freedom of speech, exactly.

PEM: Right. If you wanted to add a couple more words, the title could be The Case Against the Concept of Free Speech. I’m not against people speaking. I think that would be a fascistic stance to take. I’m against the idea that there’s such a thing as “free speech,” especially for dispossessed, oppressed people in the United States. Speech that leads to good things—working-class justice, equal rights, etc.—often comes at a very high cost: death, imprisonment, or other forms of government repression. It could be argued that truly free speech exists for no one, because we already universally accept limitations on our speech (for example, you can’t walk into someone’s house and yell at them, because private property rights trump free speech rights). But speech is freest in this country for people with more money and power. Basically, the ability to speak—and maybe more importantly, the ability to be heard—falls along the usual lines of everything else in this country: race, class, gender. And our insistence on the US as a place with “free speech” masks all that.

SSE: In the book, you talk a lot about the ACLU—famously, an organization on the left focused on the defense of free speech. Did your feelings or thoughts about the ACLU change as you were writing it?

PEM: You can’t write this story without talking about the ACLU, because for more than 100 years they’ve been at the forefront of that ever-moving line of what speech is protected. And writing it really did change how I thought about them. In some ways, it helped me understand their current stance of defending reprehensible people—like being on the side of the Nazis in Charlottesville, pushing for their permit. If you look at the ACLU’s caseload, like 99% of the causes they’re taking on are progressive, and then 1% are these things they always get yelled at about. I did some interviews with people there, even though I ended up not including any of them in the book, and the argument they made to me was that they’re not just willy-nilly taking on conservative causes—they take on causes where they think if a law is passed or a decision is made to block something, even a reprehensible cause, that will come back and be used against leftists for the foreseeable future. So that did change my thinking. Before I was just like: How could you defend a Nazi? Now I get how it’s more complicated.

I don’t want to sound like a libertarian, but that’s why I came away feeling like there is no easy legal answer to some of these questions. I don’t want to encourage laws like they have in France and other places, for instance, where people can be jailed for being antisemitic. Because you can see in Europe now, these laws are often used against supporters of BDS. In another world, maybe those restrictions would make sense. But in this world, no matter what the law is, who most often gets prosecuted? Poor people, leftists, etc.

Still, in other ways, writing the book made me a lot angrier at the ACLU in its current form. Because back when they first started, they were so much more radical, and so much more willing to take a stand on more complicated issues of speech. They were right in line with unionists who were protesting and often destroying the property of factory owners. They were more willing to defend the definition of speech as not only speech, but as working class revolutionary action in general. Now they’re much more of a middle-of-the-road organization, where they’re generally not going to take on a case that involves violence, or even a strike. It makes me think that in order to be effective at ensuring that people who have a really big problem having their voices heard—workers and poor people—do have their voices heard, they’ll have to support more radical causes and a more radical definition of speech.

SSE: You spend a lot of the book on campus politics. Why is the right so obsessed with the college campus?

PEM: The reason the right is so focused on college campuses isn’t just about protecting Milo Yiannopolous’s right to speak. It all goes back to the ’70s and ’80s, when the Koch brothers and other shady billionaires were putting money into influencing how professors thought, how college administrations thought, how students thought. The Koch Brothers’ policy advisor for 30 years, until 2015, was a man named Richard Fink, and he theorized that the Kochs and other billionaires should invest in the “raw materials” of discourse—funding scholarship, student groups, entire professorships and centers at universities, in order to achieve their policy goals. Fink and other right-wingers settled on this idea that you can’t be too honest with your goals, because then you’ll confuse the American public (or they’ll just have such a distaste for your actual goals—deregulation, lower taxes for the rich, etc.—that they won’t accept them). So instead, they pushed universalist terms like “free speech” and “market freedom.” These efforts slowly introduced the idea that money was speech, that millionaires were oppressed, that college kids and the left were a threat to freedom and democracy. There’s a reason that the Koch brothers care about free speech, and it’s because they are trying to convince us to have a certain definition of free speech that benefits them financially.

You can see a direct correlation between this strategy and the crisis of political correctness on college campuses in the early 1990s. Books like Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind and Dinesh D’Souza’s Illiberal Education sold millions of copies, and were profiled fawningly by the mainstream press—including in a Newsweek cover story that claimed college students were “thought police.” Basically, that same discourse has continued today, but the money has ramped up even more, with those same conservative groups funding a plethora of student groups (Young Americans for Liberty, TPUSA, etc.) that use free speech rhetoric to hide what they’re actually trying to do: infiltrate campuses with right-wing and fascistic thought that benefits their billionaire funders.

SSE: There are several times in the book when you say things like, “this isn’t a question about free speech, it’s about our unsettled history of racism” or “it’s a lot easier to have a debate about free speech than it is to talk about the violence that trans students face on campus.” How do we move beyond the terms of the conversation set by the right and instead center our own ideas in these debates?

PEM: First, we can begin to ignore the right’s claims to be defending free speech, because they’re propaganda, and their purpose is essentially to dissuade us from taking the action we need to take. It’s so sad to me that liberals have fallen for that ploy—the ploy created 30 years ago by a few billionaires explicitly intended to sneak conservative ideas into our discourse—and that they’ve started defending it, especially in the pages of newspapers, without really understanding what they’re defending. Meanwhile, they’re ignoring, in my opinion, other things that should be understood as free speech issues, like the fact that millions of imprisoned and detained people in this country literally aren’t allowed to talk to the outside world. That’s a much bigger free speech issue than some conservative not being able to talk on a private college campus.

Second, we can start thinking about free speech as a technology; in the same way it’s worth thinking about how we can use the technologies of capitalism to our advantage—like how you can organize on the internet—we can take free speech and make it a tool for the left. That’s not new—it’s what the left did in the 1920s, when the more radical unions were agitating for people to think of free speech not just as the freedom to speak, but also as the freedom to enact your desire: in their case, the freedom to have a working-class-controlled democracy and economy.

I think the unions of the early 1900s were onto something, because they argued that freedom of expression was not just about being an individual, but about class revolution. Leftists 100 years ago argued that freedom of expression for the working class meant the ability and freedom to enact their desire—i.e., revolution. That’s pretty cool to me, and seems correct: What is freedom if you don’t have power? What is free speech if your words and actions can’t change anything?

Sophia Steinert-Evoy is an audio producer and Master’s student in American Studies at Columbia University.