The Radical Case for the Traditional Haggadah

Leftist seders often use versions of the Passover text that articulate contemporary political commitments—but the classical haggadah allows us to make our politics our own.

THE HAGGADAH I’M HOLDING is an unpublished version created by a friend of a friend, home-printed and stapled and dotted with purple stains. Comprised of excerpts from other political haggadot of the last decades, it opens by instructing seder participants to drink the first glass of wine “in honor of the long history of Jewish women and men fighting against capitalism.” When the karpas is introduced, we are invited not only to say a blessing while we dip the green vegetable in the salt water representing the Israelites’ tears, but also to reflect on contemporary human rights catastrophes: “As we dip, we recognize that, today, there are more than 65 million people still making their treacherous journeys away from persecution and violence in their homelands.” The ritual handwashing is accompanied by original commentary: “We sanctify our hands to remind ourselves that tikkun olam is the task to which we, and our hands, are called.” This haggadah is but one of the many handmade Passover texts I’ve held over the years, lovingly created by organizers and radicals to guide their own seders. And yet as Passover approaches this year, I find myself wanting something quite different for my table.

I should say from the outset that I understand and appreciate the intention behind these contemporary reinterpretations of a very old text. Naming the grotesque injustices of the world in which we live is part of a long and painful process of coming to understand just how wrecked that world is, how much harm has been done to us, and how much harm we have caused in turn. I also know well how many American Jewish communities are deeply inhospitable to socialists and feminists, to queer people and people of color, to critics of Zionism and the modern state of Israel. Embracing rewritten haggadot that make visible the people and injustices often ignored or maligned in communal Jewish life can offer a form of solace or even function as a subtle act of resistance. By contrast, more traditional haggadot—like the classical Jewish tradition more broadly—might seem to belong to an entirely different world than the one we inhabit and the one we wish to build.

But from another perspective, the distance between the traditional haggadah’s world and our own is not a problem but a gift. In the absence of a fixed political script, we have the opportunity to be surprised anew by the ancient text and rituals, by one another’s insights and humor, by moments of connection between past generations and our own. In this light, contemporary leftist haggadot are, perhaps, attempting a shortcut: By committing a particular set of issues and phrases to the page, we avoid the more spontaneous, creative, and sometimes vulnerable act of generating commentary amongst ourselves. In offering us an opportunity for more open conversation, the traditional haggadah invites us to expand our political imaginations beyond what’s given to us on the page.

WHAT I’M CALLING the “traditional” haggadah did not, of course, emerge fully formed. While classical rabbinic literature describes many of the familiar seder elements—cups of wine, bitter herbs, charoset—the haggadah as a distinct Passover text did not emerge until the 9th or 10th centuries, when instructions for the evolving set of rituals were joined with biblical verses and extended rabbinic commentary. The wording of the haggadah itself underwent relatively few dramatic changes over the next millennium, though medieval and early modern Jewish haggadot reflected regional variations not only in ritual practice but also in aesthetics, as the text evolved to include elaborate illustrations. The haggadah’s famous account of four sons and their Passover questions, for instance, provided illustrators with a way to express cultural expectations and values, as in one early modern European haggadah that portrayed the wise son as a Torah scholar bent over his book, while the wicked son was drawn as a soldier armed for battle.

The 20th century, however, saw the rise of a new kind of haggadah, one that significantly expanded upon or departed from the text itself in order to comment explicitly on contemporary struggles. A widely-circulated 1919 haggadah created by the Jewish Labor Bund, for instance, recast the Israelites as exploited workers liberated by their own collective resistance instead of God’s mighty hand. In the US, radical haggadot came into their own with a text created by rabbi and political activist Arthur Waskow for the 1969 Freedom Seder, an event held on the first anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. for a racially integrated crowd of Jews and Christians. Waskow’s mimeographed booklet included quotes from civil rights agitators, political theorists, and theologians as well as song lyrics, stories, and passionate demands for justice. The friend-of-a-friend’s haggadah I’m holding now contains excerpts from both the Bund Haggadah and the Freedom Seder in addition to an array of more recent haggadot, like those from an Occupy Wall Street reunion seder and the Palestine solidarity organization Jewish Voice for Peace, and provides the contemporary script for an exemplary leftist seder.

The question, then, is what we are getting out of these scripts. Many contemporary leftists—I am among them—frequently worry about expressing ourselves badly, saying the wrong thing, or revealing our ignorance of something everyone else seems to know. We worry both because we don’t want to offend or harm our comrades and because we fear being judged for our own unprocessed ideas. This emphasis on precise expression of belief is not unique to the left: Philosophers use the term “propositionalism” to describe the idea that, within any community, convictions, intellectual mastery, or social acceptability can be measured by clear assent to a set of statements, or propositions. And indeed, in its broadest form, this is uncontroversial: Someone who extols the virtues of capitalism, for instance, should probably not be called a socialist.

It can become a problem, however, when this dynamic starts to crowd out other priorities, creating communities overly preoccupied with the enforcement of rules about who may speak, and when, and what may be said. And in settings dedicated to political justice, it often suggests that a deeper misunderstanding of politics is afoot. The work of building collective power requires that people begin talking openly with one another in our own (often quite imperfect) words, and hearing one another’s stories. This is always a long process: of coming slowly to trust one another, of maintaining relationships and alliances, of structure tests and strategy sessions—and of many, many errors, some with significant consequences. Anyone who has done any kind of organizing knows that there is no other way; we learn by doing, by listening to others with more experience, by erring, and by hoping that our record of errors will be helpful to those who come after.

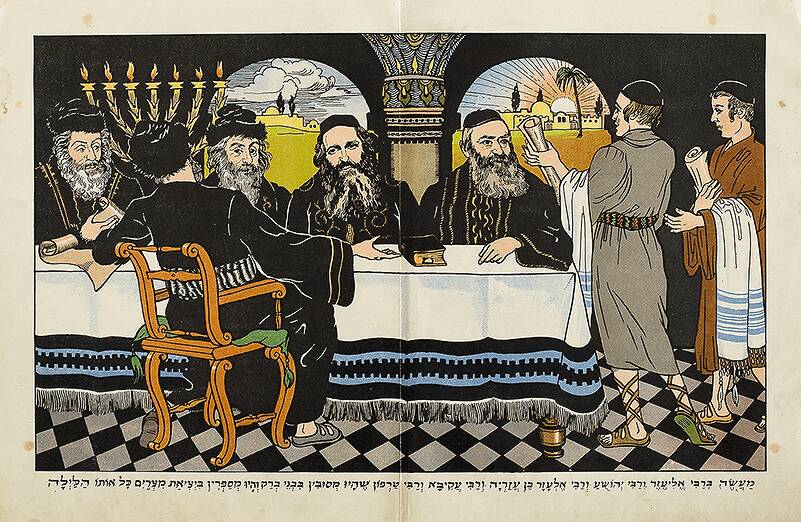

When we make impeccable ideological expression the basis of our politics, we limit our ability to trust one another with our questions or concerns. I have come to think that the preference for haggadot that strive to put our contemporary political commitments on the page in black and white contains a similar error—or, we might say, misses an opportunity. Among the various roles the haggadah might fulfill, it is clearly intended to be the foundation for sustained off-book conversation. The traditional text establishes this early on with a striking image of people lost in conversation: “It is told that Rabbi Eliezer, Rabbi Joshua, Rabbi Elazar the son of Azariah, Rabbi Akiba, and Rabbi Tarfon sat all night in Bene-Barak [Bnei Brak] telling the story of the departure from Egypt. Toward morning their students came to tell them that it was time for morning prayers.” I am not a rabbi, and I’ve never set foot in Bnei Brak. But I love this opening story because even in its foreignness, it seems so familiar: I know well the experience of staying up very late recounting past injustices, celebrating moments of liberation, and strategizing for another, better world. This image sets the tone for the whole seder. We are invited to sit back—literally, as participants are encouraged to recline at the table—and settle into the maggid, the story, in all its colorful and communal drama.

Perhaps the haggadah’s most explicit invitation to emulate the rabbis in this kind of freewheeling conversation comes in the form of the Four Questions traditionally recited by the seder’s youngest participant, who begins by asking, “Why is this night different from all other nights?” The storytelling that follows is the process of “answering” these questions—not through a straightforward reading of the biblical narrative, but through a variety of approaches: a series of food rituals that ask us to literally experience the “taste” of injustice; a recitation of the ten plagues while we spill drops of wine; and ancient rabbinic commentary on the meaning of the whole experience, like the allegory of the four sons trying to understand the Passover story. The seder’s goal, we might gather from these tactics, is not simply to read a predetermined script at one another, but to talk to one another. With the dramatic biblical narrative as backdrop, we can speculate about the motivations of the chief actors, debate the meaning of Pharaoh’s “hardened heart,” or add our own list of modern “plagues” to the traditional ten. We can ask each other questions about what we find funny or interesting or terrible in the haggadah, and listen hard to the answers. Without fixed contemporary commentary on the page, we have the opportunity to discuss what we want, unconstrained by the political choices of a given haggadah. How we make sense of the distance between the Israelites’ world and ours is up to us.

Perhaps most fundamentally, the seder is a practice of traversing this distance. Although the ritual happens year after year, and the story we tell always ends in the same way, the haggadah is designed to walk us through the journey to liberation each time. As the haggadah instructs us, “In every generation one must look upon himself as if he personally had come out of Egypt.” In the biblical moment, the rank-and-file Israelites’ assurance of their victory was by no means certain; when the people approach the banks of the Red Sea, the water rising up before them and the Egyptian charioteers at their backs, the Israelites exclaim to Moses, not without reason, “Was it for want of graves in Egypt that you brought us to die in the wilderness? What have you done to us, taking us out of Egypt?” The mandate to look upon ourselves as if we personally had come out of Egypt creates an experience of communal suspense and cooperation: Every year we hope we will end up safe on the other side.

In other words, we can experience Passover, like the Israelites, as a communal journey undertaken with great hope but without complete certainty of how it will go, or where exactly we will end up. This is the possibility the traditional haggadah presents: of being surprised by what we say and hear and experience, and thus coming to know our tradition and one another differently. It offers a vision of politics, too: one that recognizes how building power and demanding justice begin not with a set of political propositions, but with cultivating relationships and asking questions, like the rabbis of the haggadah who stayed up all night telling one another the story until morning.

Emily Filler is assistant professor in the Study of Judaism at Washington and Lee University, and co-editor-in-chief of the Journal of Jewish Ethics. She lives in Charlottesville, Virginia.