The Kremlin Ball

Ex-fascist diplomat Curzio Malaparte’s masterpiece blends the real, the improbable, and the impossible in Soviet Russia.

Discussed in this essay: The Kremlin Ball by Curzio Malaparte, translated by Jenny McPhee. NYRB Classics, 2018. 223 pages.

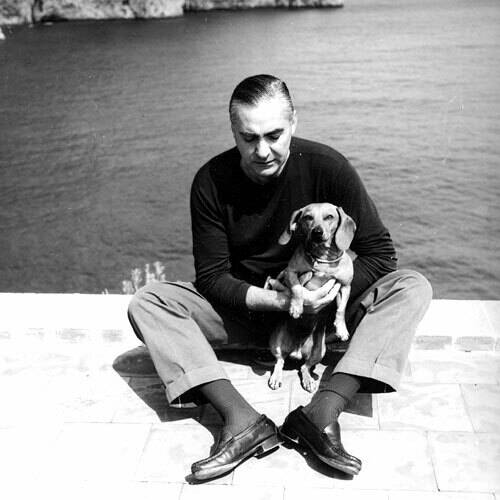

THE ITALIAN WRITER Curzio Malaparte (1898-1957) is best-known for his two semi-documentary novels, Kaputt, which covers the period the author spent as a journalist embedded with the Italians fighting alongside the German army in Russia, and The Skin, a portrait of post-war Naples. Many of the events he seemingly witnessed have struck some as so outrageous as to cast doubts on their veracity, though the charge is meaningless when leveled against works presented as fiction. Like his earlier novels, The Kremlin Ball, an unfinished work by Malaparte that only appeared in 1971, is presented as a true account of actual events. In fact, the novel is a fascinating mix of the real, the improbable, and the impossible.

It follows the doings of several Soviet figures in 1929, men like Soviet People’s Commissar Anatoly Lunacharsky, Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky, and diplomat Maxim Litvinov. But The Kremlin Ball’s air of veracity is heightened by its biting depictions of those characters who certainly are not center stage in accounts of this period of Soviet history, but who, for Malaparte, are exemplary of the state of Soviet Russia. These characters include Marina Semyonovna, the first great Soviet-trained ballerina, Lev Karakhan, supposedly the “most handsome man in Russia,” and Dimitry Florinsky, the gay Soviet Chief of Protocol, and Lunacharsky’s scandalous wife, a beautiful actress and unfaithful spouse who is guilty of wearing expensive gowns intended only for use in the plays she performs in.

It is this odd and disreputable beau monde that serves as the backdrop for Malaparte’s searing and unforgiving portrait of a new society that has already failed. Malaparte saw nothing but falsehood and hypocrisy around him, “and in a revolutionary society corrupt habits are a sign of corrupt ideas.”

As an observer—or imaginer—of Soviet Russia and its elite, Malaparte sees things few else did. “In Moscow,” he claims, “one spoke far more frequently of [the designer] Madame Schiaparelli than of Stalin—and it was no less dangerous to speak of Madame Schiaparelli than to speak of Stalin.” The sheer perversity of this observation is the essence of the Malapartean style.

And so one reads The Kremlin Ball more for its unique and off-kilter vision of the Soviet Union and the beauty of its writing than for any serious analysis of the collapsing revolution. Nevertheless, Malaparte is on to something when he says that, “What mattered to me was the manifest emergence of a new revolutionary class and I was astonished by the Trotskyists who had deluded themselves into believing that they could entraver, or impede, the rise of the new puritanical, cruel, hard, inflexible, monstrous class.” Not that those around him care about the Stalin-Trotsky split— “that boring story about Trotsky and his squabbles with Stalin,” as a diplomat describes it.

Translator Jenny McPhee gets Malaparte exactly right in her excellent introduction, saying that Malaparte’s truth “is inevitably accompanied by an aura of the incredible,” as when he represents as absolute fact Soviet experiments that involved a woman having sex with an orangutan. Malaparte, she says, writes “with a sneer and a leer, and in doing so takes the unreliable narrator to a new level.”

This is precisely how Malaparte should be read. Nothing he reports should be taken at face value, but in his death-and-decay-obsessed vision, it all could and should be true.

MALAPARTE, who served as a fascist diplomat, is supposed to have abandoned fascism and indeed to have moved to the left after World War II. Nevertheless, The Kremlin Ball demonstrates the fascination with death that was so important a part of the attraction to fascism for a certain type of intellectual, writers like the French fascist Pierre Drieu la Rochelle and like Malaparte himself, and leads one to wonder if he ever truly freed himself of it.

Death is the subject for a kind of mini-essay that closes the book. Malaparte theorizes that “Christ introduced into the classic world the horror of death. Communism took it further by introducing into the Christian world the shame of death. As such, communism was a characteristic of modern life.” He is obsessed with corpses, asking Litvinov to visit a morgue, and being met by blank stares. Do the Soviets even have morgues? “Communism returned Christianity to its deep, programmatic, fundamental contempt, not of death, but of the corpse.”

But if for Malaparte “Communism replaced the Western fear of death with the shame of death,” it nevertheless fetishized a dead body, that of Lenin, whose “mummy” Malaparte discusses several times in The Kremlin Ball, and at the end of which he visits for the tenth time. Lenin’s body, “the mummy[,] was decomposing, becoming flaky, soft to the touch, damp and spoiled.” This rot (earlier he speaks of the body being eaten by rats) is Malaparte’s final statement on the Soviet Union, on humanity, on hope.

Mitchell Abidor, a contributing writer to Jewish Currents, is a writer and translator living in Brooklyn. Among his books are a translation of Victor Serge’s Notebooks 1936-1947, May Made Me: An Oral History of My 1968 in France, and I’ll Forget it When I Die, a history of the Bisbee Deportation of 1917. His writings have appeared in The New York Times, Foreign Affairs, Liberties, Dissent, The New York Review of Books, and many other publications.