The Gamified Occupation

A Fauda-themed escape room in Tel Aviv gives customers a taste of military rule.

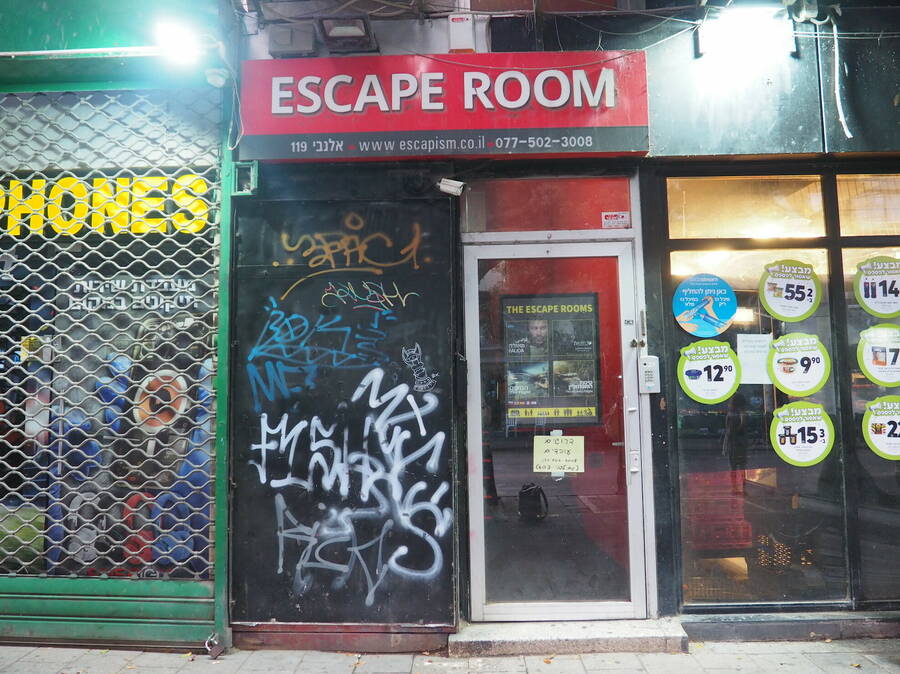

The entrance to the Fauda-themed escape room on Allenby Street in Tel Aviv.

My friends and I removed our blindfolds and took in our surroundings, blinking. We were in a hospital examination room filled with battered and outdated medical equipment, decorated with photographs of Al Aqsa Mosque and a map of the 1948 UN partition plan for Israel/Palestine. On a desk in the corner, an old computer flickered to life and began playing a video of the actor Lior Raz, in character as the commander of an Israeli counterterrorism unit who he portrays in the hit Netflix series Fauda. Raz informed us that we were in al-Shifa Hospital, the largest hospital in the Gaza Strip. Hamas militants had planted a chemical bomb in the building that would go off in 60 minutes. Our mission was to find and defuse the weapon before it annihilated all of Israel. “The fate of the country is in your hands,” he said.

In the real al-Shifa Hospital, the hallways are perpetually crowded with people in need of care; repeated Israeli bombardments and a 15-year blockade have left the facility understaffed and undersupplied. But here, we moved between deserted rooms, listening to the sounds of gunfire and distant shouting in Arabic that were piped in over shoddy speakers. To complete our mission, we had to solve a number of puzzles: Numbers written on the blades of a ceiling fan provided the password to a computer that played a video commemorating the hospital’s 40th birthday; the number 40 opened a lock that revealed a key, which in turn opened a medical office that we ransacked in search of more clues. We saw no one except for three life-sized cardboard cut-outs draped in keffiyehs and hijabs, lurking just outside a window. They buckled after one of my friends aimed and fired repeatedly with an air gun.

We were in the Fauda escape room, a collaboration between the producers of the counterterrorism thriller—whose fourth and final season will air on Netflix in January 2023—and the series’ Israeli broadcaster, YES Israel. Since the room opened in 2018, it has sat between a pizza place and a falafel shop on Allenby Street, a historic and perpetually clogged thoroughfare in central Tel Aviv, drawing a steady stream of Israeli teenagers and Jewish tourists who pay 120 shekels ($35) apiece to masquerade as Israeli agents deployed in the Gaza Strip.

The room is only the most popular manifestation of a new Israeli leisure economy that began to take shape in the late 2010s, which offers consumers a gamified taste of Israel’s military rule over Palestinians. Israelis can now host corporate offsites at fake military bases (also an extension of Fauda’s IP), throw b’nei mitzvah parties at military shooting ranges, and send their children to “Counterrorism 101”-themed summer camp. Teenagers buy video games that recreate IDF command rooms during the Yom Kippur War, or drop bombs on Gaza via an app. And the Fauda escape room is far from the only one of its kind: Others offer visitors the chance to play Mossad agents sent to “neutralize” a threat in Syria or sabotage nuclear facilities in Iran.

Though consumer demand for sanitized war games, which recast the horrors of occupation as a form of titillation, grew in a period when the reality of military rule seemed to be receding from Israelis’ everyday lives, this violent “experience economy” has continued to draw customers in a moment of escalating bloodshed: 2022 was the deadliest year for Israeli civilians since 2008, with 27 people killed in attacks, including 17 inside Israel and 10 in the West Bank. (Israelis are estimated to have killed more than six times that many Palestinians in the same period; more Palestinians have been killed in the West Bank in 2022 than in any year since 2005.) Right-wing ethnonationalist politics are ascendant, with elected officials calling on soldiers to shoot Palestinians for throwing stones, and promoting the unrestrained bombing of schools and hospitals in Gaza.

As the glorification of violence becomes increasingly mainstream, the militaristic leisure economy mirrors and reinforces the national mood. Muhammad Ali Khalidi, a professor of philosophy at CUNY who has written about Fauda, told me in an email that experiences like the escape room shape cultural and political consciousness, constructing Manichean narratives in which Israel’s occupation appears as a morally straightforward matter of survival. “It serves to justify Israeli state violence in the real world,” Khalidi said.

It’s the black-and-white nature of these scenarios that makes them appealing to consumers. “We did not expect many people to watch a show that deals with the conflict,” said Avi Issacharoff, a former undercover operative turned war correspondent who co-created Fauda with Raz. “Most Israelis don’t care; they don’t give a damn about the conflict.” Perhaps part of the show’s draw, he suggested, was that it reimagined counterterrorism and intelligence work—which, in reality, are high-tech and low-risk for the Israeli operatives who fly drones through neighborhoods they may never set foot in—as analog tests of smarts and daring: Fauda’s agents embed in the occupied territories, communicating over flip phones rather than employing zero-click hacking tools. In the escape room, likewise, consumers sprint through a storyline in which the Israeli protagonists—rather than dominating Palestinians through military force—are presented as underdogs with everything on the line. As Issacharoff puts it, Fauda is popular because it’s exciting. “What would you rather watch?” he asked. A show about intelligence operatives sitting at their computers? “Or a show about two warriors—one Palestinian and the other one Israeli?”

The escape room fad took off a decade ago in the US, where consumers displayed an eagerness to pay hundreds of dollars to fight flesh-eating zombies, derail runaway trains, or—in one Jewish-themed example in Brooklyn—flee marauding antisemites intent on carrying out a pogrom. The trend arrived in Israel in the mid 2010s and quickly assumed a distinctively militaristic cast. At that time, the violence of the Second Intifada had been replaced by politicians’ promises to “shrink the conflict” by, among other things, leveraging innovations in technologized warfare. Though the proliferation of biometric cameras and drones did not alleviate the brutality of occupation from the perspective of Palestinians, it allowed many Israelis to more easily ignore what was unfolding on the other side of the wall. Fewer soldiers than ever were deployed into combat, while less and less violence spilled over the Green Line. In Screenshots: State Violence on Camera in Israel/Palestine, anthropologist Rebecca Stein describes how the occupation gradually disappeared from Israeli political discourse and everyday life during these years—an erasure that, Stein writes, “amounted to an implicit agreement within mainstream Israeli society, fostered by the state, to keep the military occupation out of sight.”

As the decade dragged on, younger generations of Jewish Israelis sought out pop culture narratives and consumer experiences of an occupation that continued to structure national consciousness even as it faded from view. In a recent interview, Stein argued that these derived their popularity from their ability to make the occupation palatable to Israeli consumers, who jumped at opportunities to “engage with military violence in highly controlled ways that do not rebound as a critique of Israeli society and government policy.”

Perhaps the most successful example was Fauda the series, which became an international sensation the moment its first episode hit Netflix in 2016. In its coverage of the first season, The New York Times argued that the show offered a counterintuitive form of escapism, connecting its success to Israelis’ desire “to visit places and engage with subjects that they ordinarily avoid—and then return home safely with the flip of a switch.” Though the series brings the occupation into viewers’ living rooms, the Times noted, its appeal may lie in making its abuses feel more remote: The audience can “peer across the barrier wall at some of the ugliest aspects . . . then retreat to safety while consoling themselves that it’s all just make-believe.” Like the escape room it would later inspire, critics say Fauda reduces the brutality of Israeli military rule to a source of adrenaline-soaked entertainment. Its special operative protagonists are heroes in tight black V-necks and distressed denim who juggle amazing sex lives with frequent, daring rescues of Israeli civilians. Their Palestinian antagonists are portrayed as extremists who are motivated by personal vengeance rather than national liberation. (When the show hit Netflix, Palestinian leaders of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement decried it for glorifying Israel’s war crimes and called on audiences not to watch).

It’s easy to see how this approach to the occupation could become the basis for a gamified consumer experience like the Fauda escape room. But Israel’s military rule is often characterized by a gaping asymmetry in military power that involves very few “warriors,” at least in Issacharoff’s sense. Neither the soldiers who monitor AI-powered drones from the safety of fortified military bases nor the ones who shoot unarmed civilians bear much resemblance to the heroes of popular simulations of warfare. And still, some parts of the escape room do take a cue from reality: In 2014, Israel dropped bombs within yards of the real al-Shifa Hospital, in flagrant violation of the Geneva Convention and the UN General Assembly resolutions on warfare. In response to international condemnation, Israel claimed that Hamas had been using the hospital as its headquarters. This was never corroborated, but it set a precedent; in the years since, Israeli strikes have repeatedly targeted medical facilities across Gaza, debilitating a medical system that was already struggling to care for the thousands maimed by Israeli snipers and aerial bombardments.

In the fantasy world of the escape room, my friends and I raced against the clock. By the time we reached the final room, we had only a few minutes left before the bomb was set to be launched into Israel. In a last ditch effort to save the country, the IDF instructed us to initiate a controlled detonation, destroying the hospital and densely populated surrounding neighborhood instead. Our commander counted down the seconds over the speakers. The sounds of gunshots and distant shouting grew louder. Finally, we cracked the code, and our commander urged us to escape before the hospital blew up. We ran out into the light of the reception room, the sound of an explosion muffled by the door swinging shut behind us.

Sophia Goodfriend reports on automated surveillance and digital rights from Tel Aviv. She is a PhD candidate at Duke University.