The Beloved Defiles the Hands

virgil b/g taylor’s Minor Publics, on display at Artists Space through April 23rd, 2022

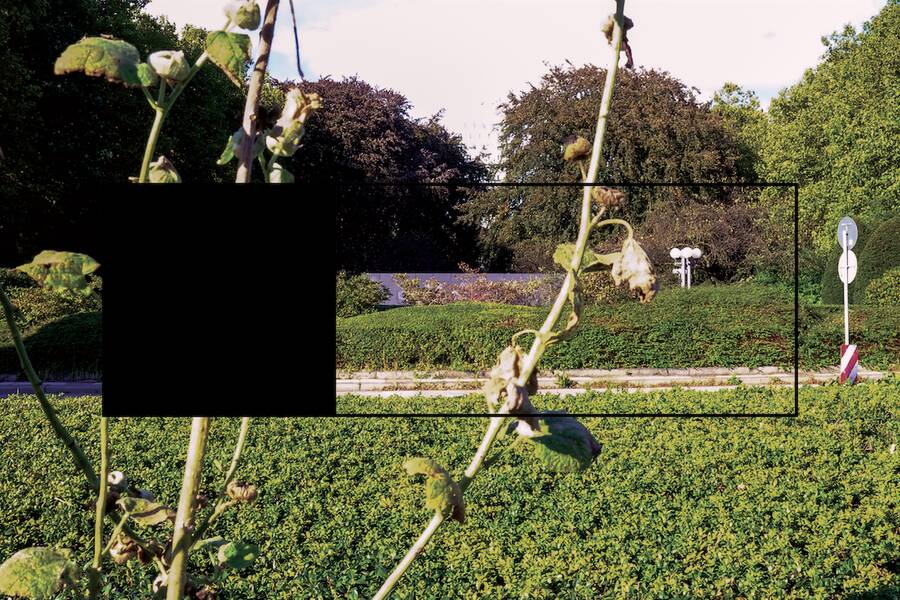

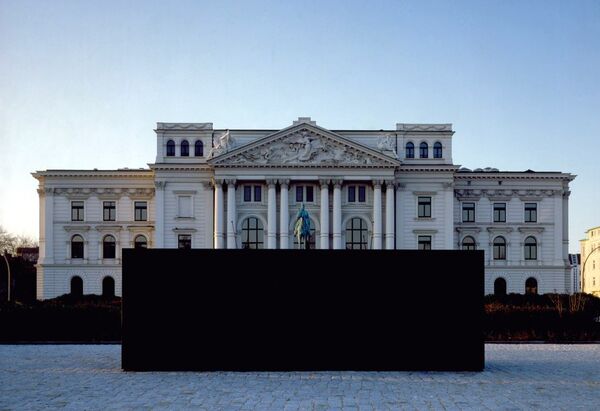

Sol LeWitt, Black Form (Dedicated to the Missing Jews), 1987, painted concrete block, 80 x 217 x 80 in

Collection: Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg, Kulturbehörde, Hamburg, Germany. (Acquired from the artist)

1. The artist encounters Sol LeWitt’s 1987 Black Form—Dedicated to the Missing Jews. That black bar of absence, the sepulcher.

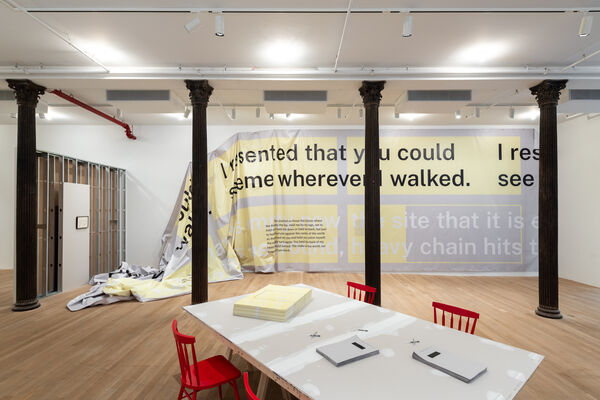

2. LeWitt’s piece is not here—it is site specific, its site is elsewhere—but the record of the artist’s encounter with Black Form is all around you: the construction diagram, the exhibition guide, documentation of the work’s demolition.

3. In Black Form, LeWitt deploys abstraction, a languageless disruption of dark stone; but here there is a deluge of text. Words cascade off the walls, pool on the floor, are stacked in printed matter.

4. Here is a table, here is a chair. A call to study, an invitation to annotate. Here are pens, here are books, here is a well-lit, comfortable space. Stay a while. Do not treat this as a gallery, do not walk the perimeter with hands clasped behind your back, do not gaze at the art for an appropriately polite amount of time and move on, taking nothing with you.

5. This is an undertaking. You must take steps to take part.

6. Consider the role of ritual in the process of inquiry.

7. Throughout the space, text repeats: The impurity of the toucher, rendered unprepared for the rest of life, or rendered such that they require a moment of preparation for life—a break from the ordinary, profane. The impurity of the toucher, rendered unprepared for the rest of life . . .

8. Note the resonance with Mishnah Yadayim 4:6. The Sadducees say, The more precious something is, the more impure it is. The Pharisees agree, if the beloved defiles the hands, we will not make profane use of holy things. The artist is borrowing, in their methods, from Jewish law.

9. What must we undertake to demarcate the time of the sacred—the time spent with precious objects of study, that render the toucher impure—and the time of the profane—the rest of life—to make ourselves ready for inquest? And then, how do we prepare ourselves to return from a consecrated interval, to a different, unhallowed temporality?

10. The exhibition guide describes Minor Publics as “exploring the boundaries between art and memorial.” Elsewhere, LeWitt’s public memorial-cum-art structure: a black form in the landscape indicates the missing.

11. Here, the black form is reimagined by the artist as presence, as platform, as bima. A place from which to speak (fuck), a sacred (profane) tribune. The exhibit text is, in fact, titled, “Bima, or בימה, or βήμα, or other words asking you to bring yourself forward and name the lines that hold you in place.” The artist writes, “I pushed you against the center of the world, so that as I turned on you and held you within myself, the world might turn again. You held the back of my head as the world turned.” and I, the reader am the you, or maybe I’m not, sometimes it’s delightful not to know.

12. What, then, happens to the boundary between monument and stage, body and text, you and me? Are you fucking or praying? Am I wrestling an angel or reading a holy book?

13. From 1897 to 1941, a monument to Kaiser Wilhelm I—who, along with the Prussian Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck, united the German Empire in 1871, paving the way for German imperialism in Europe and in Africa and Asia—stood in the courtyard of the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster. In 1941, the monument was dismantled, the metal donated to the German war effort. LeWitt placed his art-cum-memorial structure on this site of no-monument for the 1987 Skulptur Projekte. Black Form stood eight bricks high by 12 bricks wide.

14. Did you know that cinder block is made from a mixture of cement and ash? I do not think the hold of masonry on the Jewish imagination is lost on LeWitt. The Universität Münster rejected a permanent structure; LeWitt’s work was demolished by bulldozer in 1988. It was recreated in 1989 outside the City Hall in Altona as a memorial to the murdered Jews of that German borough—but the work’s original site remains empty. Take from this what you will.

15. We are called to the bima to speak.

16. If there is no bima here except the text, if the bima has been bulldozed or if it is actually a sculpture that you’re not supposed, technically, to climb on top of—then make the bima into a practice.

17. Here is a place to step up and speak from. Perhaps others passing through will stop to listen, a minor public. Make a space where a site is offered and where one is not; when something is destroyed, speak of it forever and constantly. Make of loss a liturgy.

18. The literary critic Harold Bloom identifies a Jewish “obsession with interpretation.” I see this in the artist (and myself) as I sit at the table, reading. If you take the poster home with you, please note the valence of Jewish jurisprudence in the text: “The impurity of the toucher, rendered unprepared for the rest of life…”

19. When you revisit the poster, contemplate the demand for care and attentiveness in the treatment of precious things. Consider the role of ritual in preparing to study. Consider the mark that encountering the sacred makes on the body—the impurity transmitted by an encounter with the precious—and how to prepare to return from the consecrated to the ordinary rest of life.

All photos by Filip Wolak, courtesy of Artist’s Space and virgil b/g taylor.

Solomon Brager is the author of the graphic memoir Heavyweight (William Morrow, 2024) and the director of community engagement at Jewish Currents.