The Ginzburg Geography

Jewlia Eisenberg’s posthumous album pays tribute to histories of Jewish anti-fascism.

1. Rock star, scholar, archive lover, linguistic lush, wild queer weirdo, anarchist, anti-fascist, lay cantor. New Yorker through and through, community builder, teacher, visionary, eternal student.

2. Jewlia Eisenberg was fearless. She could convince you to be, too. And, damn, she had style.

3. As a shy goth kid growing up in the rural northeast, I downloaded Jewlia’s 2001 album Trilectic and listened on repeat as she sang about communist sex and self-possession. On my favorite track, Jewlia insisted that dreams could be a substitute for the kinds of connections that were impossible in real life. Her music helped me to dream of the life I wanted: full-throated, unafraid, and rigorously unclassifiable.

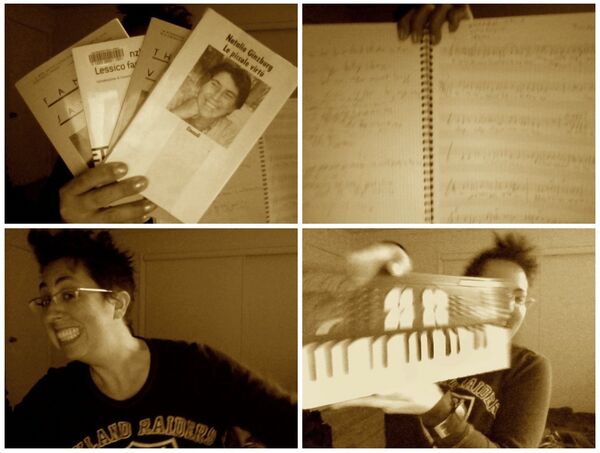

4. Ten years later, I met Jewlia while volunteering on the construction of the interactive sound sculpture associated with her 2010 album The Bowls Project, which explored fifth-century Babylonian Jewish women’s amulets. I confessed that I had stolen all her albums online. She laughed and gave me all her CDs.

5. Over the next decade, our friendship blossomed in coffee shops and at parties. Her bandmates embraced me in my exuberant fandom and my whole self.

6. On the morning of March 11th, 2021, following years of health struggles related to a rare gene mutation, Jewlia died.

7. She left us with a new, posthumous album, The Ginzburg Geography. The project traces the movements, memories, and political passions of Italian Jewish anti-fascist writers Natalia and Leone Ginzburg, revealing the intricate interdependence between politics and place.

8. Across the cities of Turin, Abruzzo, and Rome, Natalia and Leone fell in love; they went into internal exile in the remote village of Pizzoli and organized against Mussolini’s forces and the German invasion. On February 5th, 1944, at the age of 34, Leone died of injuries he sustained at the hands of Nazis.

9. When Jewlia emerged from a protective coma in early 2020 and learned to walk and speak again, she delayed her bone marrow transplant and went into the studio to record this final album.

10. If you flip open the sleeves of the paper CD case, you will find Jewlia in her own words. “I wanted to touch on how the fervor for justice can be like a religious calling,” she writes, “if your religion is freedom.”

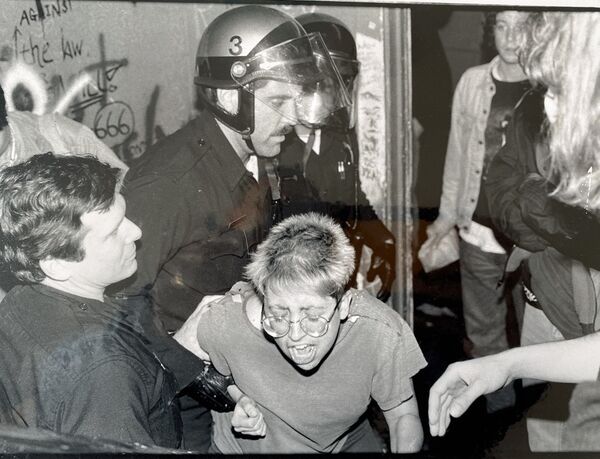

11. A commitment to freedom was at the heart of Jewlia’s Judaism. It ran unwaveringly through the course of her life.

12. Here she is at 19, defending the squat she lived in. The space was, in the words of the San Francisco Chronicle, “Berkeley’s last student bastion for radical behavior.”

13. Here she is at 50, covering the Woody Guthrie classic “All You Fascists Bound To Lose.” The song, one of the last tracks on the album, feels frighteningly timely—but only if we misunderstand the present as cordoned off from the ongoing realities facing the many of the communities most dear to Jewlia and maybe to you, too.

14. You find yourself singing along to the eclectic mix of tango, swing, Bay Area punk, and incantation—the chorus “Revolution! Revolution!” unfolding on your own tongue, in real time.

15. Amidst it all—the pandemic and lockdown, immense personal health risk and growing white supremacist movements—Jewlia stayed playful and daring.

16. “La, la, la,” Jewlia sings, fearless and upbeat, as she takes on the collective voice of anti-fascist working women, observing “if freedom doesn’t come it’s because there’s not enough unity! And the scabs and the bosses, they’re kind of tight so we should kill them all.”

17. She had a soft spot for radical intellectuals in love. Setting the work of the Ginzburgs to music alongside covers of working class freedom songs, Jewlia calls us to remember not only those who fell on the battlefield but also those excluded from the partisan song legacy: the anti-fascist writers who gave their lives for the struggle.

18. On track six, “Guerra di Popolo,” Jewlia is on the harmonium pulling long sighs from it. She languidly recounts in full and resonant notes the war of the people. She tells the story through Leone Ginzburg’s eyes, singing of the sacrifice required for a free Italy and a free Europe.

19. Toward the piece’s end, Jewlia’s voice grows more powerful than the A/V equipment can bear. She leans backward, as does the trumpet, belting long notes skyward. The sound distorts. Taking a breath, she turns to the camera briefly and smiles.

20. That’s just how I remember her. With more force than all the world she’s left behind.

Ianna Hawkins Owen is an assistant professor of English and African American Studies at Boston University and working on a first book manuscript Ordinary Failure: Diaspora’s Limits and Longings.