The Art of Irreverence: Martha Rosler’s War on Complacency

“What I’m saying is, history’s a bitch.”

WHAT DOES IT MEAN to be a political artist? It’s a question that has animated the work of Martha Rosler for the past 50 years. Since emerging in the mid-1960s as a pioneer of feminist conceptual art, she has continually returned to themes of war, gender, imperialism, globalization, and gentrification, incisively dissecting the ideological underpinnings of everyday culture. But Rosler’s notion of a politicized art practice extends beyond subject matter. In the face of an art world dominated by posturing and profiteering, she remains committed to the idea that art might genuinely occupy a social role: to demand that the public sphere be truly public, to mobilize as much as critique. Though her work has taken varied forms—including video, installation, photography, performance, and text—her central strategy is the use of what she describes as “decoys”: “a lure that attracts attention by posing as something immediately—reassuringly, attractively—known” so that it might be opened up to a productively destabilizing scrutiny. As Rosler writes in the introduction to her 2004 book Decoys and Disruptions, “I retain the hope that in some small measure my work can help us ‘see through’ the commonsensical notion regarding things as they are: that this is how they must be.”

Martha Rosler: Irrespective, a compact survey of the artist’s career at New York’s Jewish Museum, was the artist’s first major retrospective in the US in nearly two decades. Arriving amidst the cultural reckoning of #MeToo and the relentless horror show of the Trump presidency, the exhibition seemed particularly timely: few artists have engaged more persistently or more rigorously with the media’s production of political reality, or the intersections between gender, race, and class. While it is tempting to say that Rosler’s work is now more relevant than ever, the exhibition’s overarching message is that it has rarely not been relevant; if decades-old projects still seem to speak uncannily to the present, it’s because we as a society have failed to fully internalize the lessons of the past. As Rosler quips in the exhibition catalogue, “What I’m saying is, history’s a bitch.”

Rosler was born in Brooklyn in 1943 into a middle-class Orthodox family and attended a girls’ yeshiva until high school. Though she rebelled against the strictures of her religious upbringing, particularly the entrenched gender roles, she has often cited her religious education as formative to her understanding of social justice, even if she only fully recognized this in retrospect. She studied painting as an art student at Brooklyn College in the early ’60s, a path that seemed increasingly untenable against the backdrop of the women’s movement and the escalation of the Vietnam War. “The 1960s brought the delegitimation of all sorts of institutional fictions, one after another,” Rosler writes in the 1994 essay “Place, Position, Power, Politics.” “When I understood what it meant to say that the war in Vietnam was not ‘an accident,’ I virtually stopped painting and started doing agitational works.”

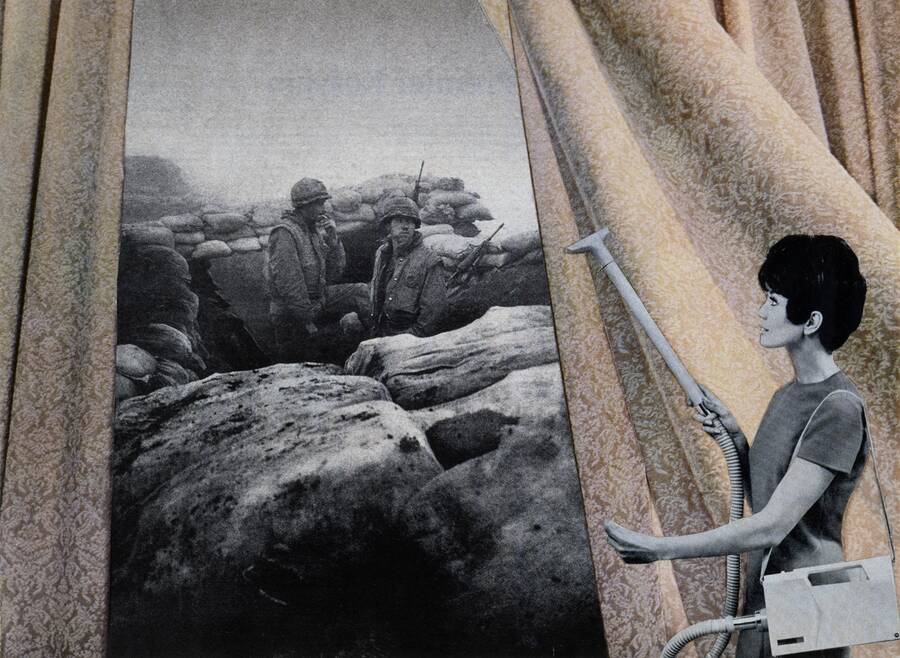

Taking her cues from John Heartfield’s Weimar-era compositions for the communist magazine Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung, Rosler turned to photomontage, repurposing imagery from popular magazines in order to make the social fissures they concealed explicit. The Jewish Museum exhibition opened with two series of photomontages that Rosler began in the mid-1960s: Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain (1966-72), which examined the commodification of women’s bodies, and the breakthrough House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home (1967-72), arguably still her best-known body of work. Juxtaposing illustrations of tasteful interiors from décor magazines like House Beautiful with documentary photographs of the Vietnam War contemporaneously published in Life, the latter series crystallized the stakes of what New Yorker critic Michael J. Arlen called the “living room war,” wherein scenes from Vietnam were broadcast into every middle-class American home on the nightly news, comfortably consumed from a distance. In Rosler’s photomontages, that distance—mental and physical—is elided. In one image, Cleaning the Drapes, a stylish young housewife straight out of a vacuum cleaner ad effortlessly dusts the ornate damask drapes of her living room, only to find, as she lifts back the curtains, that the view outside the window is one of soldiers in the trenches rather than a manicured suburban lawn. In First Lady, Pat Nixon poses for a portrait in the White House residence, the gilt-framed painting over the mantle behind her head replaced by a photograph of a war victim’s bullet-riddled corpse. The effectiveness of these works owes as much to Rosler’s compositional adroitness as the symbolic confrontation she stages: the tableaus stitch together aspirational domestic elegance and militarized violence with an uncanny seamlessness, as if to make clear that their relationship extended beyond the TV screen.

Image courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

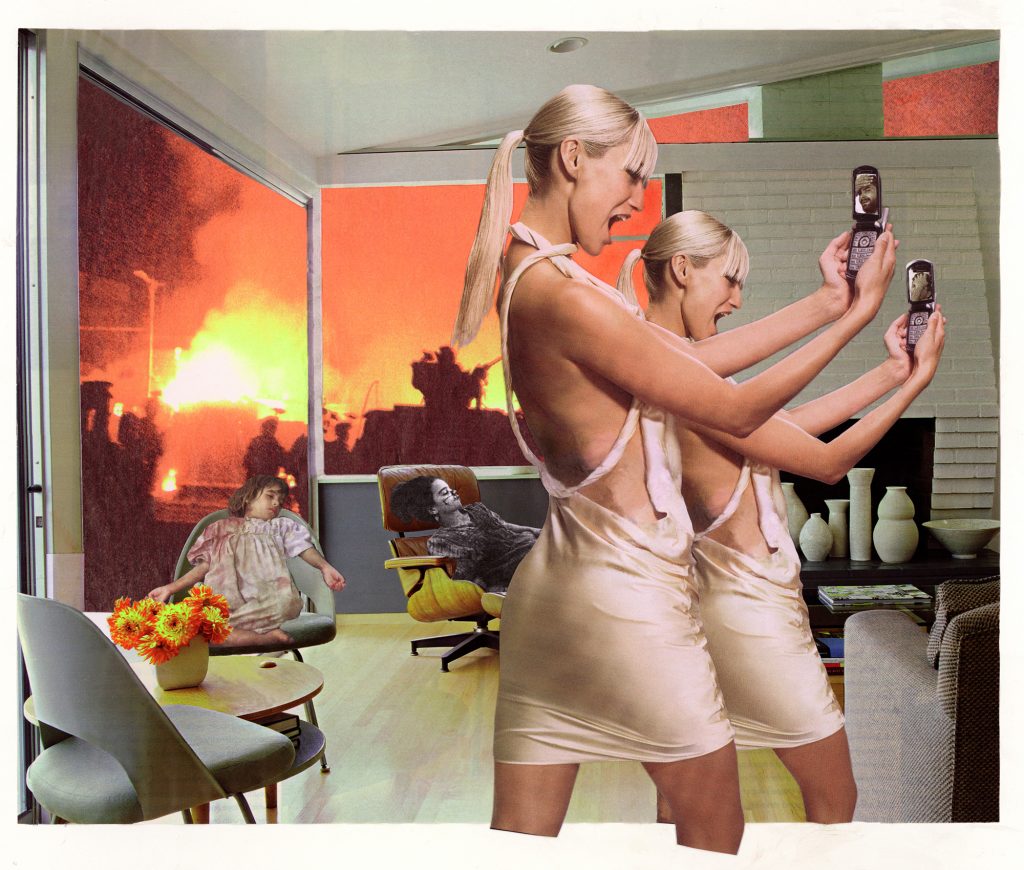

Rosler originally distributed the House Beautiful series in the form of photocopied fliers at antiwar demonstrations, or in underground leftist publications; they weren’t exhibited as artworks at all until the early 1990s. Recognizing that their categorization as “protest images” rather than art had by that point rendered them invisible, Rosler hoped that a change in context—even one that framed them within “a much more restricted universe of discourse than [she] had aimed for earlier”—might bring the works and their message back into public consciousness. In 2004, she reprised the series, this time employing images from Iraq and Afghanistan. The settings and stylings disclosed the shift in time period—in Photo Op (2004), a lithe blonde model poses with her camera phone, her chic condo’s floor-to-ceiling windows revealing a scene of fiery doom and destruction—but Rosler’s approach was otherwise unchanged, a gesture that emphasized the continuity between one imperialist war and another, and the ongoing ease with which civilians at home were able to compartmentalize what they saw on screen. As Rosler has described, returning to Bringing the War Home was also intended to “repoliticize” the original series, which had by that point been absorbed into the art world, reminding the works’ new audience that they were more than aesthetic artifacts of some past struggle.

In 1971, Rosler moved to Southern California to begin an MFA at UC San Diego, a hotbed of student activism where her professors included Herbert Marcuse and Fredric Jameson. Alongside peers like Allan Sekula, Eleanor Antin, and Fred Lonidier, Rosler began to analyze the conventions of documentary photography, particularly the classicizing social documentary forms of the 1930s typified by Farm Security Administration photographers like Dorothea Lange. For her work The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems (1974), Rosler photographed the length of the Bowery during a visit to New York—at the time, still Manhattan’s Skid Row—and paired the images with text panels listing synonyms for drunkenness. Invoking the sort of gritty urban subject favored by modernist documentarians, Rosler refuses the voyeuristic urge to represent the homeless alcoholics who tended to congregate in Bowery doorways, instead showing only their traces: empty bottles, scattered trash. As Rosler explains in the 1981 essay “In, Around, and Afterthoughts (On Documentary Photography),” the liberal humanism of most documentarians, however well-intentioned, bracketed social ills like poverty and homelessness from their structural causes, offering up individuals to pity from afar. “Liberal documentary implores us to look in the face of deprivation and to weep (and maybe to send money, if it is to some faraway place where the innocence of childhood poverty does not set off in us the train of thought that begins with denial and ends with ‘welfare cheat’),” she writes.

If there is a unifying theme running through Rosler’s work, it is an interest in how the conventions of representation produce and reinforce codes of behavior, on both an individual and a societal scale. Much as her critique of documentary photography hinged on the response these images were designed to provoke in the viewer—empathy, but also disidentification—her video works of the ’70s and ’80s scrutinized the operations of mass media to unveil how they cultivated a complacent public. Influenced by the wave of feminist performance emerging from alternative art spaces in California, Rosler began to appear in her own work as a performer, adopting the relatively new medium of video precisely because of its analogy with television.

In the video Vital Statistics of a Citizen, Simply Obtained (1977), male doctors measure Rosler’s body inch by inch, while female attendants in white lab coats periodically use sound effects to rank where each measurement falls in relation to the “average.” In a voice-over, Rosler delivers a monologue on the relationship between bodily control, social surveillance, and subjectivity, weaving in references to the use of physiognomic measurements in racist pseudoscience and the litany of everyday crimes against women, ranging from job discrimination to foot-binding and illegal abortion. By contrast, Semiotics of the Kitchen, a parody of televised cooking programs, relies on deadpan humor, as a straight-faced Rosler displays an alphabetized array of kitchen implements for the camera one by one. Her demonstrations become increasingly menacing as the video proceeds—she stabs wildly at the air with a knife, thrusts a rolling pin out at the viewer—articulating a pent-up rage at forced routine. The works differ in tone, but both amplify already-existing social cues encoded in seemingly benign elements of everyday life. Though their low-fi production values mark the videos as belonging to another era, part of the strength of Rosler’s work is its tendency to take on accretions of new meaning as time goes on: from the vantage of the present, a work like Vital Statistics seems like a portent of today’s widespread biometric surveillance.

Rosler’s work has often posed challenges to curators and critics insofar as it resists neat categorization: she has employed diverse mediums and formats, never settling on a signature style, and has addressed an almost overwhelming range of subjects, often returning to larger themes—food, war, domesticity, mass media, urban space—again and again from different angles. Doubling as a portmanteau of “irreverent retrospective,” the exhibition’s title, Irrespective, hints at the inherent impossibility of condensing Rosler’s oeuvre into a coherent narrative arc. It also points to her longstanding suspicion of museum conventions. For much of her career, she preferred to work outside the mainstream art world entirely, circulating her work almost exclusively in alternative, noncommercial contexts. Even when she works within institutions, Rosler’s exhibitions are often structured around points of friction between content and container.

In 1989, asked to create an exhibition for the Dia Art Foundation, then still located in SoHo, Rosler transformed the galleries into a forum on housing, homelessness, and gentrification, collaborating with the self-organized homeless activist collective Homeward Bound, who were invited to use the space as a temporary office during the run of the show. The project’s title, “If You Lived Here . . . ” was taken from a real estate ad for downtown pieds-à-terre targeting affluent suburban commuters (“If You Lived Here, You’d Be Home Now”), invoking the role of art galleries and institutions like Dia—and the types of people who tended to visit them—in the gentrification unfolding directly outside the gallery walls, and removing the possibility of a passive, detached encounter with the exhibition’s materials. Even when their formats are less overtly subversive, Rosler’s exhibitions never allow the viewer to conceive of the museum as a sanctuary separate from the world; adopting a caustic, Brechtian humor, she calls attention to the frame, implicating both institution and viewer.

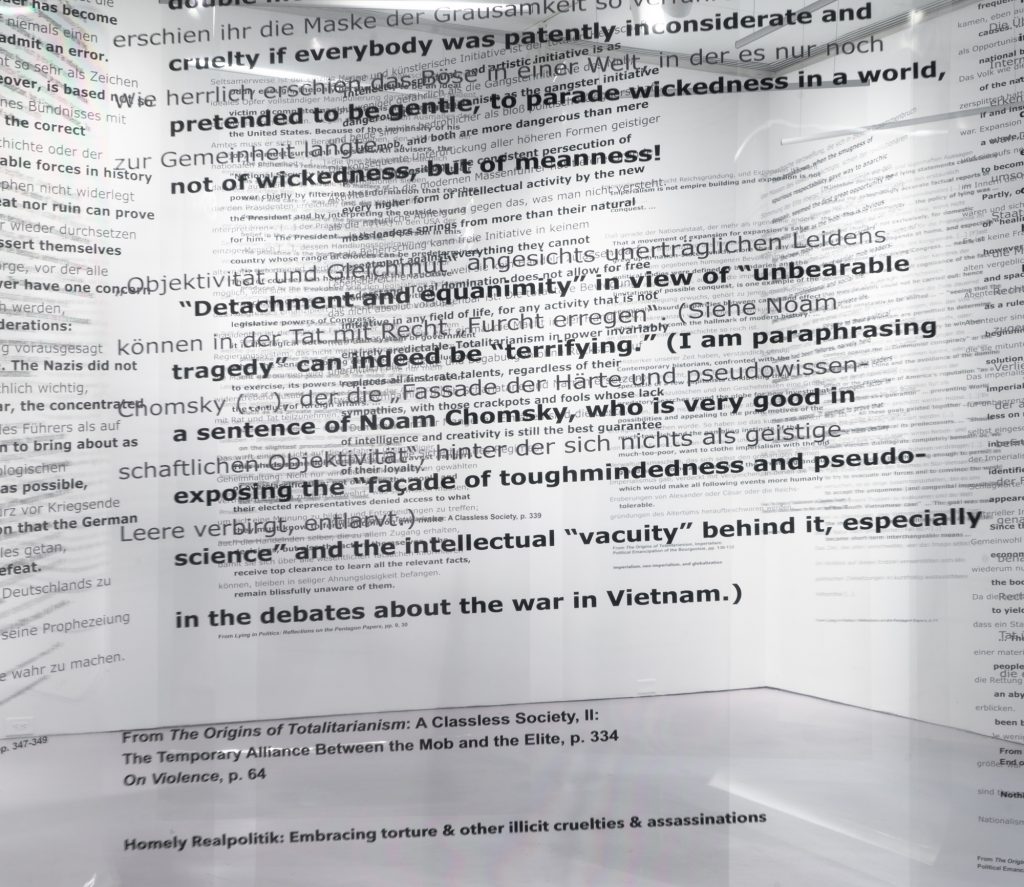

Work pictured: Detail of Reading Hannah Arendt (Politically, for an Artist in the 21st Century), 2006, installation with texts on vinyl panels printed with quotations by Hannah Arendt in German and English.

Courtesy of the artist and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York

Rosler’s most recent work has inevitably looked at the election of Donald Trump. Irrespective came full circle in the final gallery, where two works home in on the rhetoric of Trump and Pence, respectively: The digital collage Point and Shoot (2016) bears a photograph of the president pointing aggressively at the camera, overlaid with his infamous brag about being able to shoot 5th Avenue pedestrians without consequences and a list of the names of innocent civilians murdered by police, while the video Pencicle of Praise (2018) is a montage of news clips highlighting Pence’s sycophantic expressions of public praise for Trump. At the gallery’s center, mediating the two, was a work from 2006 that nods to the pedagogical origins and aims of Rosler’s project as a whole: Reading Hannah Arendt (Politically, for an Artist in the 21st Century), a set of clear mylar panels printed with excerpts from The Origins of Totalitarianism. The panels were hung from the ceiling at different angles so that the printed texts shifted and overlapped as the viewer moved around them, alternately occluding and reframing the emblems of grotesque power on the surrounding walls.

Encountering these works in the gallery, I found them heavy-handed and unresolved, as if Rosler isn’t finished processing Trump’s rise to power or the media’s dysfunctional response to it yet. But I lingered on the installation’s title—the idea of what it might mean to “read politically”—long after I left the show. A self-described “child of the sixties,” Rosler has, from the outset of her career, approached her work as a tool for consciousness-raising above all else, asking the viewer to take nothing for granted and leave no received wisdom unexamined. Regardless of my ambivalence about the success of these objects as artworks, I suspect she would consider my ongoing reflection the greater victory.

Rachel Wetzler is an art critic based in New York.