Taking Care

In the Twin Cities over the past week, protesters refused the state’s mythic monopoly on care, and thus its thin alibi for its violence.

LAST THURSDAY, we gathered, masked, members of a true crowd for the first time in months. We stood outside the Third Precinct in the dusk hours before it burned. We could see the Target that had been looted the previous evening; the air was clouded with smoke rising from the remnants of the melted AutoZone. In front of us, the crowd grew increasingly dense, oriented toward a megaphone that amplified an incohesive set of messages. Now, a young Black person decrying the destruction of property, encouraging bystanders to deter and film anyone partaking. Now, a young Black person offering the gentle transition—“Let’s hear it for self-expression”—and then, “I looted and I’d do it again.” For the moment, no cops in sight. A cluster of white people lounged on a roof behind us, their purpose and allegiance unclear. Each motorcycle revving made us flinch. It was a profoundly polyglottal space, in message and in form.

Later that night, the dispersed languages of dissent briefly cohered into a dominant gesture as protesters breached, overtook, and torched the workplace of the four cops who murdered George Floyd. We watched the event on Unicorn Riot’s livestream from our respective apartments—one in St. Paul, near the capitol building, where in the ensuing days protests would begin to coalesce; the other in south Minneapolis, a few miles from the precinct and closer still to 38th and Chicago, the intersection where Derek Chauvin had asphyxiated George Floyd three days before. The building burned; the sweeping symbolic resonance of the police precinct as a beacon of anti-Blackness collapsed into localized material destruction.

Destroying state property in the wake of the state murder of a Black man, in a nation founded on the conflation of Black people with property, inverts the logics of racial capitalism by insisting on a hierarchy that subordinates property to Black life. In this context, destroying the precinct was a form of care as well as a form of protest. The protesters registered their dissent in a language that refused the grammar of the state. The message was clear: No.

The state heard this refusal. Its boundaries of spatial order having been transgressed, it responded with the erection of more boundaries—this time, temporal. The next day, the mayors of each of our twinned cities announced a curfew for Friday and Saturday; the governor issued his own for good measure. (The curfew has been extended every few days; though it expired early this morning, it’s unclear whether it will be reinstated.) The day, the curfew asserts, is the zone of the legitimized “peaceful protest,” the airing of grief and grievance that responds to the killing of George Floyd and—though the state rarely mentions this explicitly—hundreds of years of systemic anti-Blackness. The night, the curfew tells us as it draws a line across the borderland of dusk, is for looting, for chaos, instigated by “outside agitators” whose purpose has nothing to do with the civic mandate of the day.

The curfew came couched in the language of public safety. In fact, however, it represented an attempt by the state to assert the legitimacy of its own violence. The state tells us to stay inside where it’s safe; meanwhile, it provides a new cover of legality for police to disseminate tear gas on peaceful protesters, shoot paint canisters at people enjoying the evening on their own porches, and crowd jails during a pandemic, when enclosed proximity promotes transmission of a potentially fatal illness.

The state has made little secret of the fact that it is not interested in our well-being. Crucially, though, its claim to be the indispensable provider of care for its citizens is critical to the perpetuation and escalation of its violence. If we rely on the state for care, then the state is authorized to “defend” us by any means necessary. In the coming days, as protests erupted around the country, spurred by the actions in Minneapolis and countless other grievances, municipal governments leveraged care as a tool of compliance. Chicago Public Schools stopped distributing meals, until activists pressured elected officials into reversing the decision. Los Angeles closed Covid-19 testing centers. In our cities, public transit was suspended as armed enforcers of the curfew—cops and the National Guard—filled public buses. Despite official claims that such measures are meant to keep people safe, they make a clear threat: Comply with the erosion of your freedom, or risk violence. Which is to say: You were never free here.

As with spatial mandates, the temporal ones were broken as soon as they went into effect. Defying curfew, people marked themselves ungovernable according to the state’s conditions of governance. They refused the state’s mythic monopoly on care, that thin alibi for its violence. On the first evening of the curfew, one of us contravened it, sneaking up to the Fifth Precinct, where another protest had emerged. Contrary to the state’s narrative that those who are out at night mean only harm, nearly every person, most of them seemingly heading toward the precinct or home from it, offered well wishes: Stay safe. Be careful.

The free distribution of care has spread through our cities, a thrilling rebuke to the scarcity that the state, following the logics of capital, has produced through its wildly uneven distribution of resources. At Pimento Jamaican Kitchen—on the same street as the Fifth Precinct, about a mile further north—supplies were being gathered. There were granola bars and diapers and masks and gloves, hand sanitizer and canned tomatoes. There was pasta; there were pregnancy tests. One of us added to the stacks of water bottles crowding the sidewalk. It wasn’t clear who was organizing and who had just jumped in to help, who was giving and who was taking. A child with a broom tugged at her mom’s shirt, apparently impatient to get on with her work. “We’ll get it where it needs to go,” a woman piling water bottles told a man who asked how provisions were being transported and to whom, and the question felt foreign, for a moment, a remnant of the old world where need had to be proved in terms legible to state power or highly regulated nonprofits. Here, by contrast, the policy was simple: People who needed things took them. They took them because they needed them. That was the point.

Outside the precinct, too, care was plentiful as people kept watch on the streets and via their phones, sharing news of the placement of police as people protested and looted a nearby gas station and set the edges of a Wells Fargo ablaze. (All banks partake in an extractive project that is fundamentally racist, but Wells Fargo in particular has made a name for itself with high-profile practices of fraud—including those targeting members of the Navajo Nation—and investment in the Dakota Access Pipeline.) Someone reported that a SWAT team was nearing, and a group of us fled. The next night, confusion mounted as news spread on Twitter that a white supremacist had shot 12 rounds at Pimento. When asked about the incident, an employee demurred, seemingly—understandably—uninterested in “help” from authorities. “Our store is safe and our community won’t let our store be anything but safe,” he said. What exactly happened is unclear from where we stand; it has proved difficult to get good information on the ground. We have only ad hoc networks of care, subject to error as well as campaigns of misinformation, and a government invested in spreading fear.

Indeed, the uncertainty that characterizes these days feels, to a significant extent, conjured by the state. The curfew—with its regular incremental extensions, its irregularly timed phone alerts—and the occasional shutting-down of highways have generated disorientation. The hope, it seems, is that when it’s not clear what one can or should do, one will do nothing but stay inside and wait for normal life to resume. (Two days ago, in an article noting the expiration of the curfew, a local newspaper announced: “Signs of normalcy are slowly taking root.” The article was later revised after the governor extended the curfew for two more nights; the line about normalcy was removed.)

The decentralization of the movement abets our uncertainty; there is no leader to simply follow. Still, there are compasses: In the Twin Cities, Reclaim the Block, Black Disability Collective, Black Visions Collective, and other groups have long been cultivating alternatives to white supremacy. The conditions for another future feel expansively underway. A Sheraton hotel has been converted into a shelter for the unhoused; they’re seeking volunteers with experience in de-escalation to coordinate the residents’ safety. Multiple members of the Minneapolis city council have announced an intention to “dismantle the Minneapolis Police Department,” and to investigate “what it would take to . . . start fresh with a community-oriented, non-violent public safety and outreach capacity.” Today, Rep. Ilhan Omar voiced her support for this proposal. Reforms are passing at an incredible speed, after years of relentless advocacy from organizers; already the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Public Schools, and the Minneapolis Park Board have severed ties with the police.

Yet there have also been frightening advances in unfreedom, embodying and exacerbating already-existing forms of violence: the “contact tracing” of protesters, the military occupation of our streets. These things won’t be easily rolled back, and must not be passively accepted. The new spaces of critical rupture, too, require vigilance to ensure that they are conduits for total transformation. This includes questioning the conditions of the rupture itself. It was the filmed murder of a cisgender Black man that broke the world open, but to truly abolish the conditions that led to George Floyd’s death, we also need to recognize the police murders of Breonna Taylor, a Black cis woman, and of Tony McDade, a Black trans man, as world-ending emergencies. On Monday, a mob of mostly Black cis men brutally beat Iyanna Dior, a Black trans woman here in Minneapolis. That, too, should end this world and catalyze the birth of another, because the world that keeps Dior safe would also be a world in which the men who harmed her would not be hunted.

Abolitionist and prison scholar Ruth Wilson Gilmore defines racism as “the state-sanctioned or extralegal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death”—a state of affairs hideously exacerbated in recent months by the Covid-19 pandemic, which has disproportionately affected Black people, including Floyd himself, who tested positive for the virus in April and had recovered. That disproportion is likely to be further intensified now, as Black people gather to protest Black death—a vulnerability that underscores the protests’ impossible urgency.

We are writing this from the space of turbulent unknowing, from that deeply imaginative interlude before things coalesce around a form. The unknowing unfolds in hesitation, in venture, in conversation. The radical incoherence that can create a threat to us finding each other also feels like the condition of possibility for other ways of being. As the already-restricted possibilities of the presidential race narrowed, this ruptural opening loudly insisted on another way—one that refuses to be resolved within the terms of the current system. And decentralization is the movement’s very strength. The state has sown discord in the hope we will run back to it for safety. But we’re on our way elsewhere. Now, we check in nightly with each other. We see how the other is doing, what the other has heard, whether the other plans to go out after dark. We wonder what to show up for. We show up as best we can.

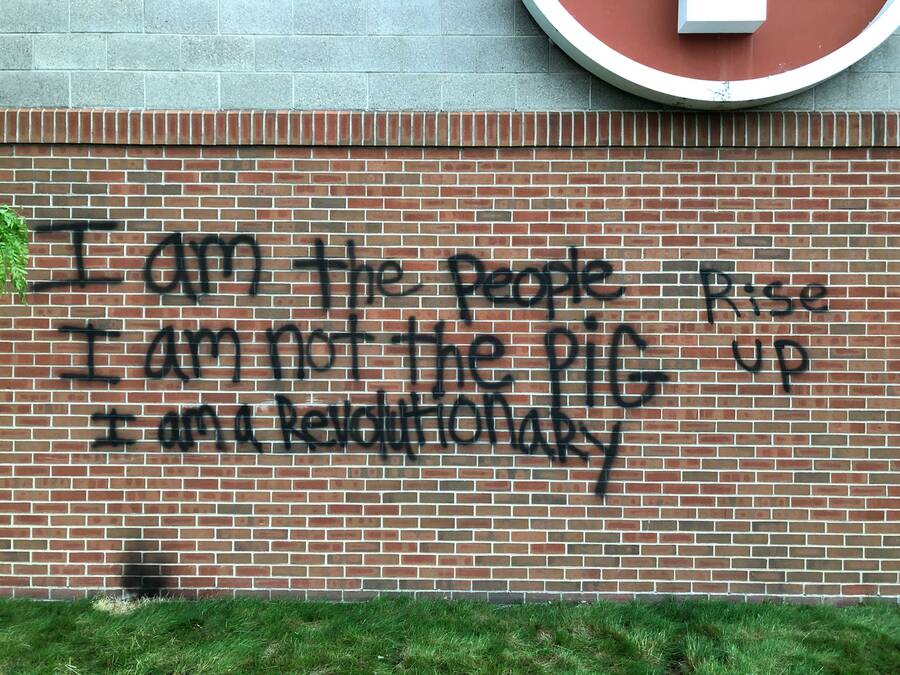

Over the past week, our cities have been filled with graffiti, slogans and images—repurposing the walls of banks, police barriers, and boarded-up storefront windows as protest signs. The cohesive statement of the burning of the Third Precinct has dispersed into many refrains, reiterated across the cities: Justice for George. No peace. Fuck the police. One message, written on the brick of the building across the street from the Fifth Precinct—one that has not, or not yet, been burned—declared, riffing on Fred Hampton: I am the people. I am not the pig. I am a revolutionary. Rise up. This morning, after the curfew faded, one of us passed by this building to find that someone had scrubbed its surface in an attempt to erase the message. The words themselves are gone, but their afterimage lingers.

Nathan Goldman is the managing editor of Jewish Currents.

Claire Schwartz is the author of the poetry collection Civil Service (Graywolf Press, 2022) and the culture editor of Jewish Currents.