A Strangeness Inside Your Self

Hélène Cixous discusses writing as a woman, the meaning of Jewishness, and the impossibility of understanding.

This article is part of a folio on Hélène Cixous. Click here to read the rest of the folio.

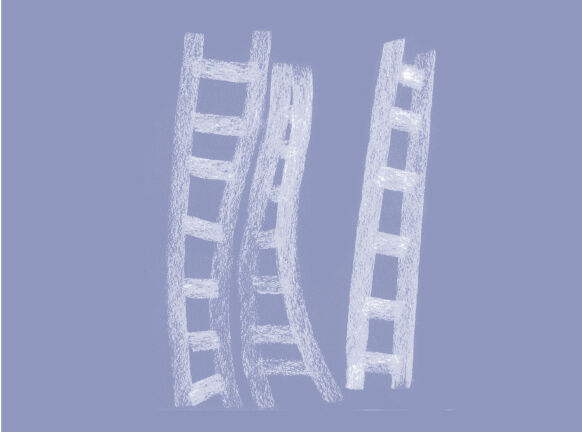

Claire Schwartz: In Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing, you tell us, “Writing and reading are not separate, reading is a part of writing. A real reader is a writer. A real reader is already on the way to writing.” But while I tend to think of interpretation as making manifest this indelible link—for example, in the Talmud, where exegesis becomes the basis for extending the text—you seem skeptical of interpretation. You write, “The dream’s enemy is interpretation . . . It wishes to make the dream cough up.” What do you mean, then, when you say that reading is a part of writing?

Hélène Cixous: Writing and reading are adventures. You don’t try to catch meaning. You let it gallop like wild horses in front of you or beside you, and just enjoy the experience. I don’t exclude interpretation, but it is limited. It belongs to a certain type of practice, which is scientific, methodical. It belongs to the sphere of psychoanalysis where, indeed, you try to make dreams tell the secret. But dreams are secret; their power is in resisting interpretation. What I call writing is very close to weaving the tapestry of dreams.

What dreams give you is marvelous: You’re surprised all the time—and you feel at once that the dream has something to say to you, and that you don’t understand. But not understanding is part of understanding. Every time somebody tells you, “I understand,” you may be sure they don’t. There’s nothing to understand. You have to receive, to react emotionally—but not catch.

CS: What does catching kill?

HC: Derrida says, “Dès qu’il est saisi par l’écriture, le concept est cuit.” Once it’s caught by writing, the concept is cooked. It’s dead. And it’s true: You’ve tried to fix it, but it is mobile. The concept flies away, emitting sparks—and as you receive the sparks, you’re astonished and enchanted. The moment you want to catch it, you lose it.

CS: The Egyptian Jewish poet Edmond Jabès sees this lack of fixed understanding as the very condition of language. In The Sin of the Book, he writes: “The Tablets of the Law were broken when still only barely touched by the divine hand . . . There is no real first understanding, no initial and unbroken word.” For Jabès, the word—a mark on the blank field of the page—distances us from the primordial nothingness of creation, but also touches the void by displacing the thing in the world to which it refers. Negating as it asserts, the word ceaselessly renews its relationship to nonexistence, becomes strange to itself. I thought of this idea when I encountered your formulation: “Why do we desire to die so much? Because we desire to say so much.” Might you say a little bit about the relationship between writing and death?

HC: Writing was born for me when my father died. I lost him very early. But he gave me death, and death and I came into a dialogue then: Who will be stronger? Is death going to kill me, or is it going to give me visions, inspiration, courage inside the awful experience of a terrible weakness? I think art is always answering to the threat of death. But you don’t throw yourself into it. You just answer.

“I think art is always answering to the threat of death. But you don’t throw yourself into it. You just answer.”

CS: With language?

HC: Yes. But language is not only words. Everything speaks. We are always at school with different languages. There’s the language of colors, for example. Or, my cats have their own language, which I understand, and they understand me. I talk to them in French; I know very well that they understand French, and that if I change to another language, they have to learn other elements of language. Of course, words are granted to the human species, and they are tools with which we translate the huge book of nature.

CS: What does translation mean to you?

HC: It’s an act of reception—then you share a meal. That’s why I say, when referring to the cats: We share. We approach the same object, desire, fear, with different languages and different energies. But we meet. We exchange. We guess. That’s what we do with everything.

When I was a tiny girl, the language of God fascinated and amused me. He crackles into here. His seems to be a vegetal speech. The other species see the burning bush, and they understand what we don’t. There is an enormous amount of misunderstanding.

CS: Where do you see misunderstanding?

HC: It’s everywhere all the time. In the family, with friends—and of course it makes for wars. You open a newspaper or hear people in Parliament: It’s all misunderstanding. Aggression and misunderstanding. Speeches become weapons. But frequently, misunderstanding is love.

CS: How do you hold misunderstanding without weaponizing it?

HC: You accept that you don’t understand, that we are unable to really understand the Other. The Other remains foreign.

CS: That reminds me of your concept of the foreign home. You write that truth is “‘the miracle into which the child and the poet walk’ as if walking home . . . And for this home, this foreign home, about which we know nothing . . . we give up all our family homes . . . We go toward the best known unknown thing, where knowing and not knowing touch.” Often understanding is framed as a way of being on the inside, misunderstanding as a way of being on the outside, but you upend this binary. How did growing up in Algeria shape your relationship to understanding and misunderstanding, inside and outside, the family home and the foreign home?

HC: Algeria has been one of the main sources of happy misunderstanding in my life. In Algeria, all living beings were enigmas to one another; it was obvious no one understood any other. And of course, it caused a lot of damage—but only because people don’t accept the richness and wonder of strangeness. They insist that what is right is for everybody to be the same, to be identical and identified. Algeria was my first theater of these obvious and most-of-the-time-denied human situations.

“To be Jewish is a permanent firework of enigmas.”

CS: How did Jewishness shape your early encounters with these kinds of misunderstandings?

HC: It was fundamental. To be Jewish is a permanent firework of enigmas. It’s a kind of genie or fairy creature that accompanies you permanently—and you never know what it’s telling you, where it will lead you, if it will leave you helpless. And it changes all the time; my experience now is very long. In Algeria, it was always festering. When I was three, I had an experience of deep and infinite astonishment: I was accused of being Jewish. I didn’t even know I was, and I didn’t know what it meant—except that it was definitely a threat. And I thought: What’s that? What you are. What does that mean? It was infinite. That never left me. It has come back very often—even with my dog, who died of being Jewish. He himself would look at me and say, “So I’m Jewish, too?” Jewish in the worst way: being a victim, being sentenced to death, which he was.

But then I found it, too, when I started working on Joyce. The first determining moment in A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, his pseudo-autobiography, was the fact that he had to admit something. The word “admit”—recognizing something that you don’t recognize.

CS: When you say that your Jewishness was festering in Algeria, what did that look like?

HC: It looked like constant offense. Every day, opening the door, going down in the street, and being called “sale juive” [“dirty Jew”] or whatever. That was minor—but it happened inside a particular world-concept. This was in 1940. I knew about the war. I belonged to it. My family was inside it; I knew that all so-called nations in the world were killing one another, and that this was decided by poison words. I think my writing fate was determined then, because I kept thinking: Is there a place in the world, a star in the sky, where there is peace and love? My parents were loving, so I knew it existed inside our flat. But where else? In dreams? Then I thought: Up in the trees with a book.

CS: So it was quite literally the family home that sent you in search of a foreign home—and both feel vital to your work. Much of what you use and move through in your work is the stuff of your own life and relationships. But at the same time, you say: “I have no children when I write. When I write I escape myself, I uproot myself, I am a virgin; I leave from within my own house and I don’t return.” What does it mean to write autobiographically without fortifying oneself inside the family home, but instead moving toward a foreign home?

HC: Writing is a kind of strange relation toward your otherness, toward your questions. Who am I? I don’t know, of course. I’m asking myself, and looking into mirrors that have the power to perceive the deep images that I myself don’t see. It’s a way of discovering your secret twin, your foreign twin, your strange twin. When you write, you’re completely immersed in the pursuit of this other who live—I use the plural on purpose—somewhere in your depths and transport you into a psychic state where you must recognize, and not regret, that no one can ask you to leave your fascination. You thirst for that other, your deep self, which you can only evoke. It has the same unpresence or presence as God; we can’t do without it.

CS: So much of your writing is engaged with identities whose meaning is definitively unfixed. I’m thinking, for example, of the way you just spoke about Jewishness: It is, but what is it? On the other hand, in your early work, like “The Laugh of the Medusa,” you find political possibility in writing as a woman in a way that seems to move from that category as a stable set of coordinates.

HC: I never thought, I’m going to write like a woman. Growing up in Algeria, I was treated first as a Jew. When I was 17 or 18, I started feeling that not only did I instinctively side with Jews, a colonized people to whom I belonged, but also with Algerians—not as Algerians, but as a colonized people—and so with the colonized of the planet. But when I came to France, I suddenly discovered that I was also a woman. France was supposedly an educated country, but when I arrived I saw that it was not true! This was the fate of women generally speaking: suffering, ignorance, and social and political situations that sentenced them to being the maids of men. I started looking at my contemporaries. I said, “My God! They’re not even their own friends. They don’t even know what it is to be a woman.” What is jouissance, what is enjoyment, what is sexual pleasure? I saw that they didn’t know anything about that. That’s why I wrote “The Laugh of the Medusa.” It was as if suddenly I woke up. It was a kind of intellectual evolution. I thought: The fire is now burning with the world of women. So I have to give all my strength there—knowing that we won’t get to victory while I’m alive, that this is a struggle that will last for centuries. But being a woman who belongs to women, I couldn’t hesitate.

CS: What does it mean to be a woman? How do you feel about trans feminisms?

HC: Woman is not a cell where you’re closed in. It’s openness, it’s the ability to experience everything. I’ve been a man, I’ve been a bird. As a woman, you belong to that part of this species that has the pleasure of containing and retaining, for a piece of time, another human being, about whom, in that time, you don’t know anything; it is simply a being you carry inside yourself, part of yourself, which is not yourself. It’s a perfect and happy experience of a strangeness inside yourself—and then of freeing this strangeness.

I am completely open to trans positions; I think their limit is when they are reactions to realizing that you’re forbidden to change identities—when they become another stable, strict, limited experience.

CS: Do you think of your Jewishness as unstable?

HC: Everybody tries to escape being Jewish. There are so many examples of cowardice, it’s incredible; I’ve seen that all my life. One of my decisions—it’s a decision—from my early life is that you can’t escape it. You’re born there, exactly as I sometimes say that I cannot deny I was born in Algeria, because there is something of the earth and perfume and fate of this country—to which I don’t belong, and which doesn’t belong to me—that is part of me. I can’t wipe it out, I can’t erase it. And I mustn’t try, because I must pay my debt. With Jewishness, there is such a huge and unique heritage, which is a heritage of suffering, of persecution. And this is really one of the reasons I have to stay there, be there. Even if I am a nonbeliever, I respect the immense history of this people who inherits—which is the law for all people; we inherit, we are inheritors. To deny that is just a sign of weakness.

Claire Schwartz is the author of the poetry collection Civil Service (Graywolf Press, 2022) and the culture editor of Jewish Currents.