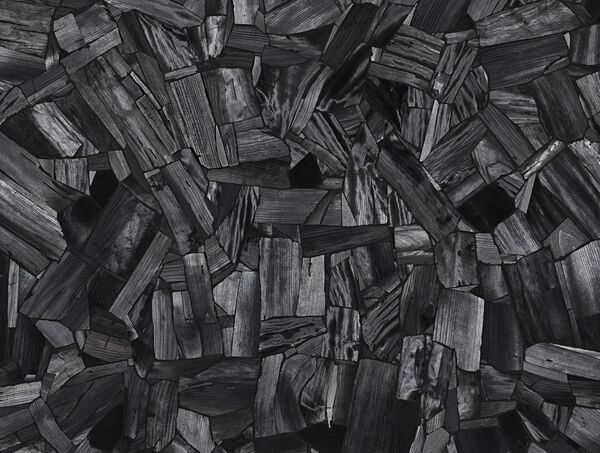

Lee Bae: Issu du feu 2L (excerpt), 1998, charcoal on canvas, 162 x 130 cm

The Nothing Letters

What might bloom in non-being?

In his poem “Psalm,” Paul Celan provocatively reimagines the form of a hymn to God as an ode to nobody. “Blessed art thou, No One. / In thy sight would / we bloom,” he writes, in John Felstiner’s translation. This holy absence soon leads him to a vision of human beings as nothing: “A Nothing / we were, are now, and ever / shall be, blooming.” Curiously, this nihilism is presented not as despairing, but as generative—a flourishing.

As friends and colleagues who often think together about the transformative possibilities as well as the limits of language, we wondered what would happen if we approached the bounds of the sayable by writing to one another about nothing. Drawing on others who have tried to think with the void, we set out to see what we might find in its contours. What could nothing teach us? Might nothing—as the most radical form of negation, a rejection of the basic terms of existence—guide us out of the obstinate fixity of the world as it is? Lingering in its non-being, what might bloom?

Dear Claire,

I admit, I’ve been neglecting our assignment, guiltily eyeing a shelf stacked with books in which the word nothing dots the page. I sit down to write, then rise and pace, leaving an empty chair to face the page, to face you.

Can a letter reach someone or only no one, say something or only nothing? “How did people ever get the idea they could communicate by letter!” Franz Kafka wrote to his lover Milena Jesenská. “Written kisses never arrive at their destination; the ghosts drink them up along the way.” Rosmarie Waldrop, Edmond Jabès’s translator, tells us that he dissuaded her from writing her novel as an epistolary text. “Letters—that makes two absences,” he cautioned. Perhaps he meant that one’s own absence, one’s own nothing, is all one can take.

I do sometimes struggle to bear it. Without warning depression descends, draining things of their meaning, rending my world; in its fog I recede from myself, become nobody. In these moments, nothing looms like an angry god.

“You say you are an atheist. How can you constantly write of God?” Waldrop asked Jabès. “It is a word my culture has given me,” the writer responded. “It is a metaphor for nothingness, the infinite, for silence, death, for all that calls us into question.” By calling God “a metaphor for nothingness,” Jabès perfects the negative theology of Maimonides, in which we can’t say what God is, only what he is not. Jabès goes further, twice: by expanding negation from claims about God to God himself, and by negating the literalism of God’s name, declaring it a metaphor. (Isn’t metaphor always negation masquerading as affirmation, something that turns out to be nothing as it reroutes us to the thing itself?) Under Jabès’s reading I begin to see God and nothing not as words at all but something else: letters sapped of sense, filled with void, ceasing to signify. Meanings vacate their offices, leave desk chairs empty, spinning.

“Philosophical problems arise when language goes on holiday,” writes Ludwig Wittgenstein, who sought a clarity that would resolve the mysteries of metaphysics. Others prefer to deepen them. In “What Is Metaphysics?”, Martin Heidegger stretches language past the point of intelligibility: “Negation is grounded in the not that springs from the nihilation of the nothing.” Following language on holiday (I picture him on the beach, the sun blanching his little Nazi mustache), he investigates the experience of anxiety, finding in it a confrontation with the nothing that is inextricable from human being. Our groundedness in nothing makes wonder possible. “Only on the ground of wonder—the revelation of the nothing—does the ‘why?’ loom before us,” he writes.

In its annihilative denial, nothing sends us searching for answers. We find these in the realm of beings, whose strangeness dims as we come to comprehend them. We stack facts like bricks, erect sturdy homes; we obsess over their solidity, press our palms against the hard clay to know no wind can breach them.

When a question turns up no answer it denies us shelter—leaves us in question, with nothing. Nothing always seems to send us back to itself, a well that quenches with thirst.

In the opening scene of King Lear, Lear’s daughter Cordelia offers him a nothing which they pass back and forth. Lear has demanded that his daughters declare their love so he can mete out his abdicated throne—an empty chair—in proportion to their affection. But Cordelia refuses:

CORDELIA: Nothing, my lord.

KING LEAR: Nothing!

CORDELIA: Nothing.

KING LEAR: Nothing will come of nothing: speak again.

Every time I read this I wish Cordelia would repeat her answer, restarting the cycle: a ceaseless circuit of nothings. What might emerge as they accrue? If the answer is obvious—nothing!—what’s less clear is just what this nothing has to offer, whether delving deeper into its depths might lead me out beyond the limits of my own understanding. Perhaps this is what I was after when, as a child, wondering what it would be like if the world did not exist, I would close my eyes and try to imagine it so (not so), repeating the word (not a word) silently to myself: nothing, nothing, nothing.

What did I gain, or lose? What might we? I wish then I’d had someone to whom I could say it aloud: Nothing! And now I do.

Nathan

Dear Nathan,

I like to imagine you as a child, saying nothing, nothing, nothing to no one, your still-new language touching the if-not of all this. I suspect that your silent nothing was close to something like chochma, that particular wisdom the Kabbalists coveted. On the tree of life, an arrangement of the ten divine emanations that comprised creation, chochma is near the top, estranged from human consciousness—beneath only keter, the incomprehensible divine nothingness that is the very condition of everything that is. Your early nothing: a child’s recollection of a formless state. “Our groundedness in nothing makes wonder possible,” you write, and I think it works the other way, too: Our groundedness in wonder makes nothing possible, the bright void of your interior eating your speech. But here I am, belatedly displacing the no one of your address—“In a field / I am the absence / of field,” Mark Strand writes; in the current of your nothingward wish, I am its negation. I catch your private utterance on its way down to the tree’s lower branches, where human finitude lives—or rather, my touch pulls it toward the earth. I’m lucky to arrive late, after your nothing-wish has been unwieldy in the world; formless, it can’t be wrangled, only sought after, listened for.

Maybe that’s what I’m seeking: to touch the formlessness denied by the fixed meanings securing the order of things. Ours are years of grief underwritten by carceral centuries. So many are gone, and so much of what remains is arrayed against naming those losses, touching them with our language. Clinging to the myths of self-sufficiency and the set route of linear progress, we confirm the ongoingness of the brutal arrangements that produced these devastations. “What is language if it doesn’t move, if it doesn’t open, if it doesn’t complicate rather than regiment?” Dionne Brand asks. “[Capital] compresses language in its meaning, in its logic of what we are good for, what we are worth, what might happen.” How, then, to mess this thingly grammar? To find the reconstitutive possibilities that press on our limited shapes?

I once heard the poet Douglas Kearney say over and over don’t stop until the words chased each other into uncertain order—Don’t stop! Don’t stop, don’t. Stop, don’t!—the competing vectors of desire jostling. I felt a nauseous thrill at the surplus of meaning (which is also a dearth) he shook out of the language by adding his sound to it. The circle he made of the words was not an enclosure, but an architecture of escape.

Nothing, nothing, nothing you said, and I picture the word as the shell of a hermit crab, each repetition foisting it up to a steeper angle, until whatever soft life was encased there could no longer cower in its little armor, steps outside. Nothing can live long like that, bare to the elements. Of being a poet, Solmaz Sharif remarked: “I think it has to do with a commitment . . . to accept only the briefest awnings as shelters . . . [then] to keep moving.”

It’s only getting later, time to move aside. If I’m quiet, I can discern something whistling in the space between the letters like wind through the branches on this sharp autumn night. Can you hear it, this minor note of nothing? Can you feel the persistence of that first language, wordless, meaningless, without articulation—

Claire

Lee Bae: Issu du feu 4N (excerpt), 1998, charcoal on canvas, 162 x 130 cm

Dear Claire,

I’ve been thinking about your hermit crab. You produced him from my nothing, but now I see him in every something, a scuttling phantom haunting any ordinary word: apple, midnight, room. Repeating each sound until sense slips away, I glimpse his furtive likeness, spy in the geometry of the letters an abdicated shell: a vacant remnant left in sand.

Paul the Apostle, an erstwhile Jew, knew what it meant to cast off language. In his second epistle to the Corinthians, he writes that God has made the early Christians “ministers of the new covenant, not of the letter but of the spirit; for the letter kills, but the spirit gives life.” I think he’s right about the letter—and not just the Law’s—but wrong about what it means to give life. As Waldrop says, language can only create because it has already destroyed the thing it speaks of: The word “kills the actual thing . . . then creates something with that death-based word.” If Paul would have us abandon “the ministry of death, written and engraved on stones” to carry forward only the spirit, the meaning, Waldrop invites us instead to tarry with the word—to linger with stones, to affirm the destruction in every act of creation. Perhaps this is what Peter Cole had in mind when he offered a Jewish rejoinder to Paul: “As a poet, I’m with the letter, not the spirit.” (What do you call a Jew who annuls the Law but still grips its letter? A Jew.)

Gershom Scholem writes that the Kabbalists’ “continuous Creation” rests on an endless renewal of nothing through the recurring process of tzimtzum, in which the infinite God contracts, creating and sustaining an emptiness for finite beings to fill: “again and again a stream streams into the void.” Just as tzimtzum unfolds over and over again, so too does the death work of language. We can see it clearly when language undoes our world and our steadiness within it (in Kearney’s unstable circuit, Brand’s insubordinate disordering). And then there are moments when words themselves seem to perish, when some once-resonant word—like God—stops sounding for us.

In your image of the crab, nothing escaped the shelter of its name. But I’m still wondering about the hollow left behind. Suppose the shell is the name of God, which I find deserted on the beach. I can’t live within it, or see it as it once was, brimming with being. But I can inspect its fine weathered splendor, trace the smoothness within. I can lift it to my ear and catch a rush of sound, inscrutable, like the traces of a long-lost voice.

Is this what you heard? Could it be that every word has, somewhere beneath its boisterous meaning, a murmuring nothing, waiting? To fill one’s pockets with shells and stones—would that be despair? Or something else?

Nathan

Dear Nathan,

When I was growing up, we had a tashlich ritual: Every Rosh Hashanah, we would go to a lake with a few other families. After we spent the bread bearing our sins, the older kids would comb the shore for flat stones and skip them along the water’s surface, leaving ripples in their wake—glyphs on the page of the water. I tried to join, but I loved jagged stones best, the ones that sought the bottom, the surface closing quickly behind them with no record of the disturbance. In Jabès’s The Book of Questions, Reb Jacob says that when a stone breaks the surface of water it is like the “divine utterance,” “silenced as soon as it is pronounced”—the rippling rings, human speech, impossible witness to what has been sealed: “Eloquence is created by the absence of a divine word.”

Jabès collected stones from the beaches he visited; he saw faces in them, stored them in a drawer that he would open to share with friends. (“Stones too are flowers, only their scent is stronger,” writes Celan.) Jews put stones on graves—to warn kohanim of the presence of a lifeless body or to keep the soul in this world or to keep the golems away or because when we pray, attempting to bind the souls of the dead among the living, we pronounce the word tzror, bind, which also means pebble. Jews leave the cornerstone of a building unpainted to commemorate the temple. The grounds for prophecy having been destroyed, only a world for interpretation remains; because the temple is gone, the world is a text. Stones are like letters, marking death.

I imagine the writer as the one who walks, placing her stones in the field, in the bed, in the boardroom, under the bridge, in the hands of the butcher: Death is here, here, here. But if to write is to bring death, to cast off the world’s verdant liveness in favor of the desiccated symbol, then to read is to make live—not to resurrect (that is the province of the spirit), but to cling to the letter as it makes its way in the world, stitching death into the task of living, bright as the ribbon on the head of the scapegoat. To write and to read: tzimtzum; the Kabbalists’ infinitely repeating stream into the void.

Anna Kamieńska writes, “Poem—a pebble tossed in the abyss.” It’s true: When I touch the void, the word is made strange to me. It is there that certainty dissolves into doubt (or, call it faith), and I know only one thing: I need you. I need you to help me restore meaning—What do you see from over there? If I put it next to my seeing, who then will I become? As Fred Moten and Stefano Harney remind us, “We must dissemble in order to renew our habits of assembly”; we must become unfamiliar to ourselves in order to find each other outside the sedimented routines of transactional relation, we must become unfamiliar to ourselves to learn how to build differently. (Things will never be quite as they were before. The Talmudists knew this, passing their readings back and forth until new ways of being opened up.) Yet, when I return to a meaning that I recognize, come again to think that I know what I think, will I remember the disturbance to knowing that’s passed through me, incontrovertible as any stone?

Your presence reminds me of my strangeness. Likely thinking of his friend Georges Bataille, Maurice Blanchot wrote: “‘The basis of communication’ is not necessarily speech, or even the silence . . . but exposure to death, no longer my own exposure, but someone else’s . . . And it is in life itself that the absence of someone else has to be met: it is with that absence . . . that friendship is brought into play and lost at each moment, a relation without relation or without relation other than the incommensurable.” For Blanchot, then, a friendship is characterized not by a common intimacy, but by a committed difference: someone with whom to face, as he writes elsewhere, “not the reducible distance but the irreducible . . . the strangeness between us.” Facing the void with you, I’ve found that friendship—the kind of love that Frank Bidart names when he writes: “The love I’ve known is the love of / two people staring // not at each other, but in the same direction.”

Claire

Lee Bae: Issu du feu 5N (excerpt), 1998, charcoal on canvas, 162 x 130 cm

Dear Claire,

Facing nothing with you, I’ve found love too—and what Blanchot’s friend Emmanuel Levinas calls “thinking that is more than a thought one can think.” He wrote that this “transcendence to the infinite” is rooted in our responsibility for our neighbor, which we can feel concretely in “the nearness of another”—the very experience of another’s presence. For Levinas, as for Blanchot, this presence is bound up with absence, the condition of its possibility. But Levinas believed this link manifests not in the absence of the other, but in the absence of a reason for being together. This intimacy has “a meaning without vision or even aiming” and unfolds as “an awaiting with nothing awaited.” The suspension of purpose liberates friendship from the onerous logics of extractive relation, which always want something. Friends meet and abide amid nothing.

It is not always easy to dwell together in nothing. When a friend suffers deeply, it might require holding silent space for the nothing that stands behind it, rather than rushing to give it meaning. After Job loses everything, including his ten children, his friends come to comfort him. When they see him, they weep and rend their garments before settling into a silence befitting his unspeakable pain. For seven days and seven nights they sit with him in the dirt and say nothing.

But as Job cries out to God in anguish—beseeching the deity to “annul the day that [he] was born”—the friends’ resolve falters; they speak and, in trying to make sense of Job’s suffering, become his accusers. Each friend insists in turn that his loss must mean something—he must have sinned to earn it, and if he repents, divine favor will be restored. They abandon him for the comfort of meaning, clinging to the faith that what has shattered was broken for good reason and can be repaired. As with friendship, to give loss purpose is to deprive it of its meaning, which is nothing.

Even as Job repeatedly demands that God explain himself, he holds fast to his innocence, and his certainty that it will not save him from his meaningless suffering. When God finally speaks, he affirms Job’s nihilism, castigating his friends: “You have not spoken rightly of Me as did My servant Job.” But then he rewards Job, and thus undermines his nihilism: God “blesse[s] Job’s latter days more than his former days,” making him rich in livestock and even granting him ten new children, son for son and daughter for daughter. Job’s loss is undone. Were his friends right all along—that good and bad fortune are allotted justly, that there is meaning in suffering?

Kamieńska once recorded a loved one’s piercing question: “Do you think the children from Job’s second chance could actually be happy?” If they could—and if he could—then repair is possible. If not, then his is a restitution threaded with its own impossibility. Kamieńska again: “I returned / to confirm / there can be no return.”

I wonder if teshuva—atonement, but literally return—is like this: return not as a viable project but as a gesture of sacred futility. When I am sorry, I touch the impossibility of repairing what I’ve broken, which is the same as the impossibility of repairing my own brokenness. Teshuva, then, is not a redemptive restoration of being but a melancholy tarrying with nothing. But in this refusal of meaning—of a healing that resolves each wound endured or inflicted into a narrative of justification—there is a bare beauty. In tashlich, as we gather in the blankness of the new year and prepare for the day of atonement, we are sorry together; we stare in the same direction, toward the lake, which for Bidart is the choreography of love. Awaiting nothing, casting our voided sins into the water’s abyss: nothing streaming into nothing. It does not forgive, does not redeem. But its silence lets ours be.

Nathan

Nathan Goldman is the managing editor of Jewish Currents.

Claire Schwartz is the author of the poetry collection Civil Service (Graywolf Press, 2022) and the culture editor of Jewish Currents.