Revising the Dream

Members of the socialist-Zionist youth group Habonim Dror North America are increasingly pushing back on Zionism’s centrality in the movement.

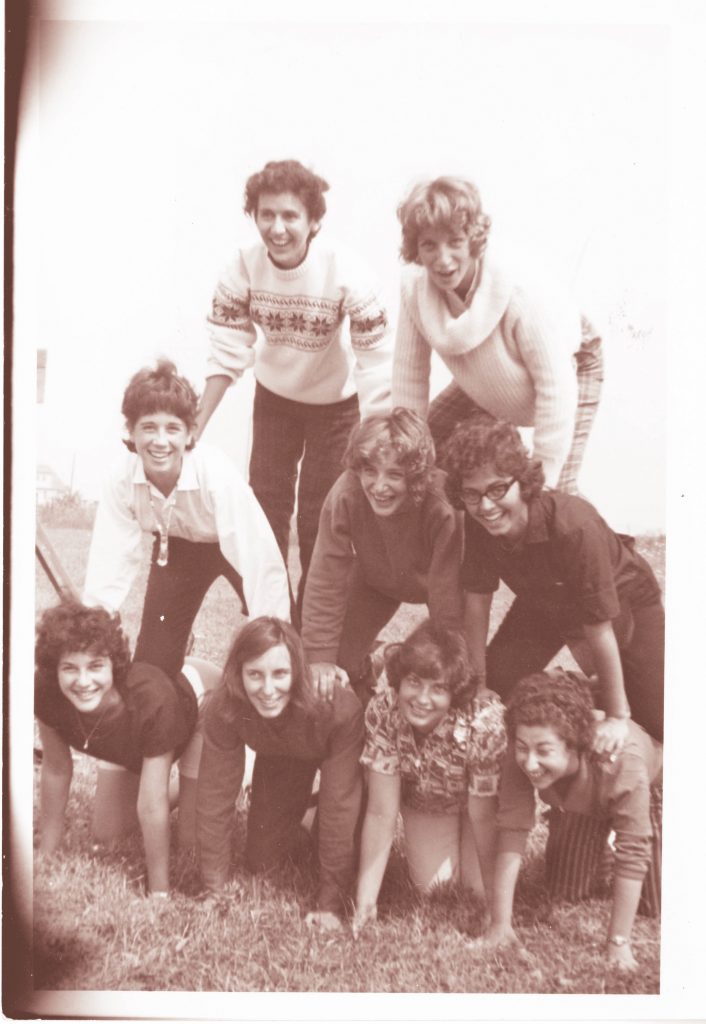

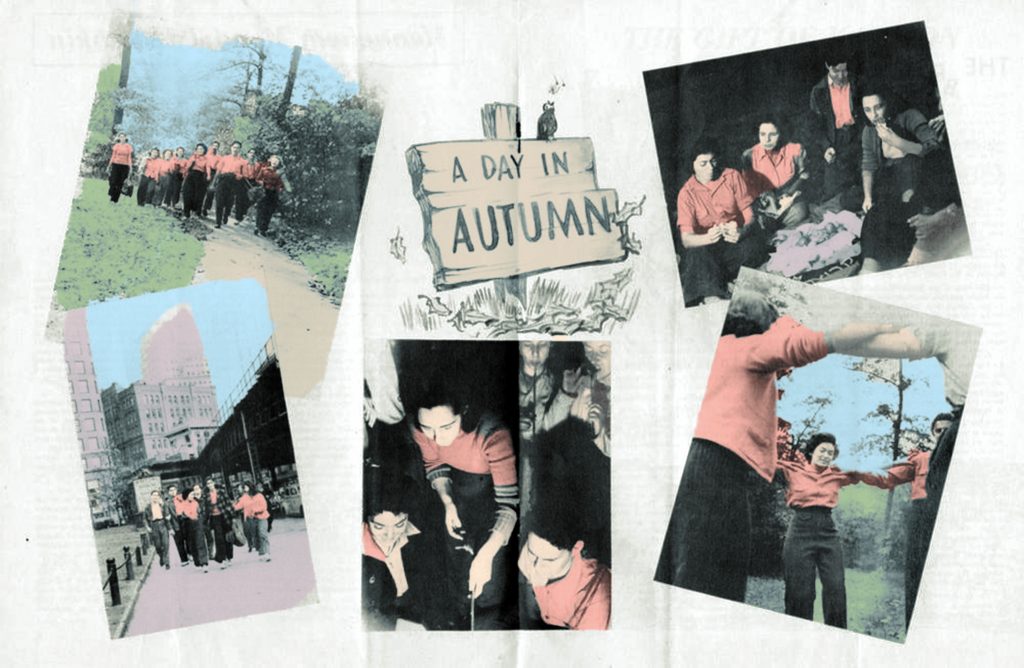

ONE NOVEMBER IN THE LATE 1940s, Marion Magid, a high school student from the Bronx, joined fellow members of the Labor Zionist youth movement Habonim on a visit to a farm in Cream Ridge, New Jersey. The farm was owned by a collection of Zionist groups, including Habonim, and used as a site for training young American Zionists—mostly city dwellers unfamiliar with agriculture—to work the land in preparation for settling on kibbutzim in Palestine. In a 1962 essay for Midstream magazine, Magid recalled walking the open country roads near the farm, sleeping by candlelight on the farmhouse floor, and sorting socks in the communal clothing storeroom—fantasizing all the while about leaving school and moving to Palestine to become a Zionist pioneer. Like most Habonim members, she ultimately did nothing of the sort; she stayed in the US, went to college, and eventually became a managing editor at Commentary magazine. But her years in Habonim left their imprint. “The astonishing thing is not that more of us did not settle in Israel,” Magid wrote, “but how those who did not were rendered permanently uneasy in America.”

Since Habonim North America’s founding in 1935, its mission has largely centered on the work of preparing members to help build kibbutzim and other structures for communal living in Palestine (or, after 1948, Israel). Unlike Hashomer Hatzair, another prominent Labor Zionist youth group established in the diaspora before the founding of the Jewish state, Habonim never strictly required members to make aliyah, the Zionist term for moving to Israel. But Habonim’s constitution frames aliyah as the ultimate way to achieve hagshama, or actualization of the movement’s values, and as recently as 2013, a study surveying nearly 2,000 Habonim alumni found that around a quarter had at some point moved to Israel, even if half of those who did so later returned to the US or Canada. Along with its longevity and its robust educational programming, the seriousness of this commitment to aliyah has given Habonim—which runs six summer camps and various youth leadership programs across the US and Canada—a stature in the North American Jewish institutional world disproportionate to its modest size.

But the relationship between Habonim members and Israel is changing. Today, many younger “Habos”—heavily influenced by the socialist, egalitarian values they learned at Habonim’s summer camps and movement seminars, and horrified by Israel’s rightward march—are now wondering whether those values are in conflict not just with Israeli government policy, but with the ethos of Zionism itself. Last summer, in a dramatic escalation of tensions within the movement, nearly 600 members and alumni of the organization now known as Habonim Dror North America (HDNA) signed a petition calling for a radical shift in the organization’s relationship to Israel. (Habonim Dror—which formed in 1982 when the worldwide Habonim movement merged with an Eastern European Labor Zionist organization, Dror—also exists in more than 20 other countries outside North America, from South Africa to Argentina, but each country’s organization operates independently.) In May 2020, Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced his intention to begin annexing portions of the West Bank: a clear violation of international law, and the latest signal of Israel’s lack of commitment to ending its occupation of Palestine. In response, the following month, several HDNA members publicly released the petition, calling on the national leadership of HDNA “to ensure that we are no longer complicit in supporting the Israeli government.” Their petition demanded that the movement end all programming within Israel—including a gap-year program known as “Workshop,” a high school leadership seminar, and a Habonim-led Birthright trip—and that it “no longer actively encourage members to make aliyah.”

The petition caused panic both within HDNA and within the broader landscape of organizations that aim to foster attachment to Zionism among diaspora Jews. HDNA’s central leadership body—a group known as the mazkirut artzit, made up of recent college graduates who work for Habonim full-time—insisted that the movement was already organizing against annexation, and defended its Workshop program as essential to “our long-term strategy to promote a just two-state solution.” Meanwhile, the Jewish Agency, the powerful Israeli para-state organization that played an integral role in Israel’s founding and now promotes aliyah from the diaspora, sent the mazkirut artzit an angry letter, urging Habonim’s leaders to purge Habos who supported the petitions’ demands from the movement or risk losing the Agency’s support in arranging visas for Israelis who come to work at Habonim camps and in its central office. (HDNA declined to do so and has been in talks with the Jewish Agency trying to smooth over the disagreement.)

Even as Netanyahu has backed away from annexation plans, HDNA continues to wrestle with an internal divide over whether moving away from Zionism would result in the movement’s certain doom or its only chance for survival. Last September, just before Deborah Secular finished her term as educational director on the mazkirut artzit, she sent an email to the Habonim listserv arguing that excising Zionism from the organization’s mission would be fatal for the movement, predicting that the change would affect its funding sources and its summer camps’ ability to attract campers, and would lead in turn to their disaffiliation from HDNA. Hazel Sher-Kisch, a petition organizer, believes the opposite is true: The movement will not survive without fundamental change. “Increasingly, [HDNA’s members] feel the tension between a more reactionary, militarized Israel and leftist values and are choosing leftism over Zionism,” said Sher-Kisch. The organization’s numbers are declining—39 members attended Workshop five years ago, but the last two cohorts before the pandemic numbered 10 and 16, respectively—and in the past several years, members have reported difficulty recruiting enough counselors to work at camps. Sher-Kisch said she believes a significant number of lapsed members she knows would still be involved if it weren’t for the focus on Zionism. “Things would look extremely different today if the movement was willing to make space for them,” she said.

Sher-Kisch and other organizers are continuing to advocate for a new approach, with more attention on diaspora-focused social justice programming that they believe will rejuvenate the movement. What remains unclear is whether a movement founded expressly to champion Labor Zionism—the ostensible reconciliation of socialism and Zionism—can survive with Zionism removed from the equation.

IN 1898, Russian Jewish philosopher Nachman Syrkin founded Labor Zionism in a pamphlet titled “The Jewish Problem and the Socialist Jewish State.” At the time, Zionism and socialism were both popular solutions for addressing antisemitism and Jewish poverty in Eastern Europe, but adherents of the two groups were at odds. Socialists believed Zionism, as a form of nationalism, was incompatible with international working-class solidarity and that the Zionist movement was dominated by elites; Zionists thought socialists were insufficiently committed to preserving Jewish community. Syrkin, however, claimed these ideologies could be reconciled, and that “[t]he socialist movement staunchly supports all attempts of suppressed peoples to free themselves.” The socialist parties in most European countries would never liberate Jews, he said, but Jews could find liberation in their own workers’ state in Palestine. Various thinkers followed Syrkin, developing strains of what would come to be known as Labor Zionism, and the concurrent mass migration of Eastern European Jews carried the ideology to the US.

Socialists believed Zionism was incompatible with international working-class solidarity and that the Zionist movement was dominated by elites; Zionists thought socialists were insufficiently committed to preserving Jewish community.

Habonim North America was founded in 1935 as a movement of autonomous youth committed to promoting and practicing Labor Zionism. From the beginning, Habonim sought out an ideological middle ground on the left. According to Builders and Dreamers, a compilation of writings on Habonim history edited by J.J. Goldberg and Elliot King, Habonim, unlike traditional American Zionism, was avowedly socialist, though less rigidly Marxist than Hashomer Hatzair, which also had a large presence in the US. By 1945, Habonim was operating 11 summer camps, where campers discussed foundational Labor Zionist texts in addition to participating in traditional scouting activities, across the US and Canada. Some teenagers learned agriculture skills on the New Jersey training farm described by Magid, and would-be movement leaders undertook intensive study of Labor Zionist ideas and the Hebrew language at a Habonim leadership institute in New York City. When the British prohibited Jewish immigration to Palestine in the 1940s, American Habonim members helped guide boats full of Holocaust refugees to sneak into the territory. When Israel’s War of Independence broke out in 1948, Habos participated in the illegal smuggling of weapons to Palestine, even storing crates of dynamite at Camp Galil in Pennsylvania.

With the establishment of the state of Israel, Labor Zionists coalesced into the Labor Party and took control of the first official Israeli government. The party oversaw the mass dispossession of Palestinians who had fled or been expelled from their land during the 1948 war, and the establishment of martial law that, until 1967, restricted the movement of Palestinians who remained inside the boundaries of the new state. Meanwhile, Zionists around the world, including North American Habonim members, rejoiced at the fulfillment of their dream. Freed from British immigration restrictions, Habonim youth could train for their eventual aliyah on actual kibbutzim in Israel; in 1951, the movement sent a cohort of members to pilot the first session of Workshop, which would become its trademark Israel gap-year program.

In 1967, Israel—led at the time by the government of Prime Minister Levi Eshkol, a founder of the Labor Party—won an unexpected victory in the Six-Day War and gained ostensibly temporary control of the West Bank, Gaza, the Golan Heights, and East Jerusalem. Many Labor leaders had never given up on the idea of a Jewish state spanning the entire area from the river to the sea—including the newly occupied regions—and settlement in these territories soon followed, justified in part as a necessary component of Israeli security. For Labor Zionists, who had long encouraged Jews to homestead the land in order to bolster a future state, settlement “was natural, like muscle memory,” said Yehuda Shaul, a co-founder of Breaking the Silence, a group of former Israeli soldiers who raise awareness about human rights violations committed by the Israeli military and teach about the history of the occupation and settlements.

With the beginning of the occupation, North American Habonim members were faced with unassailable evidence of the impact of Zionism on Palestinians. According to Goldberg and King, Habonim responded by transforming into a “militant oppositionist movement within the Zionist community”—an early voice for a liberal anti-occupation Zionism. In 1972, their national convention voted to prohibit alumni from making aliyah to settlements in the occupied territories, decades before center-left American Jewish organizations cohered around an anti-settlement position.

“Labor served Zionism, and not the other way around.”

Today, Habonim Dror North America and its summer camps exist in a much different context than the world of the movement’s founding 86 years ago. The Labor Party, which controls only seven of 120 seats in the Knesset, is no longer a viable force in Israeli politics. The party’s recent decline can be traced to a variety of factors, including the global turn toward neoliberalism and the failure of the Labor-led Oslo peace process of the 1990s. But some say that Labor Zionists’ composite ideology was incoherent from the start, and always doomed to fail. “Whenever conflicts emerged, the agenda of national revival would always prevail,” Neil Rogachevsky, an Israel studies professor at Yeshiva University, argued in a May autopsy in the conservative journal American Affairs. “Labor served Zionism, and not the other way around.”

TODAY, MOST YOUNG AMERICAN LEFTISTS see Zionism as incompatible with socialist values. The Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), for example, which historically supported liberal Zionism, has in recent years embraced a politics of Palestinian liberation in tandem with its rise in prominence. At its national conference in 2017, the organization voted to support the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement; last year, it signed on to a statement, created by the US Campaign for Palestinian Rights and the Palestinian legal advocacy group Adalah, that defined Zionism as an “inherently anti-Palestinian . . . form of supremacy.”

HDNA, however, has remained anchored in what it calls “Progressive Labor Zionism,” attempting to strike a balance between unwavering Zionism and opposition to the occupation. Because the movement is youth-led, Habonim counselors—usually older teenagers and college students—have a high level of autonomy in determining the curricula at their camps, and have often heavily incorporated anti-occupation materials. But as a result, HDNA’s educational model, with its emphasis on critical thinking and youth leadership, has prepared many of its members not to follow its path, but to question it. “In Habonim Dror, I got a nuanced enough picture that I was able to come to some of my own conclusions. Some of those conclusions were less Zionist than the organization itself,” said Mimi Lucking, who grew up attending Camp Miriam in Vancouver and participated in Workshop in 2018. Not surprisingly, Habos have played important roles in the recent revitalization of the American Jewish left; several founding members of the anti-occupation group IfNotNow, for instance, were Habonim counselors or alumni.

“What people who say that leftism and Zionism are incompatible are missing is the ability to fully dream.”

Yet HDNA members grappling with Zionism have often clashed with movement leadership. The self-selecting group that has stayed involved long enough to serve on the mazkirut artzit tends to include those most committed to Habonim’s embrace of Zionism. “What people who say that leftism and Zionism are incompatible are missing is the ability to fully dream,” said Erica Kushner, the current mazkirut artzit leader. “Many people want to be realistic, to define Zionism as it appears in its present state and no other way. But the dream of a Jewish homeland that is also a Palestinian homeland is inherently socialist-Zionist.” This sentiment is shared by the previous head of mazkirut artzit, Leah Schwartz. “Labor Zionism gives an alternative vision of Israel as a country built on equality rather than divine rule and military might,” Schwartz said.

This orientation means that while anti-occupation activism might be more robust in HDNA than at other American Jewish organizations, it still has its ideological limits. For example, counselors at Bonimot Tzedek—an HDNA program where older members engage teenage campers in year-round social justice activities in their communities—planned an event with Breaking the Silence in November 2020. In email correspondence obtained by Jewish Currents,a mazkirut artzit member told Bonimot Tzedek staff that they could proceed with the event, but that the national movement would not help promote it because “[t]he connotations around Breaking the Silence in Israel are very negative and if the name ‘Habonim Dror North America’ is used in this event, it could have catastrophic consequences on the movement in terms of our partnerships and funding.” She added that the extra caution was partly due to the impact that the petition controversy had had on HDNA’s partnerships in Israel.

This exchange demonstrates the extent to which Habonim is divided over a question currently facing many liberal Zionist organizations: Is it better to retain a seat at the table in Israeli institutions in order to influence Israeli policy from the inside—a position that might require unsavory compromises—or to withdraw completely as a form of protest? In the view of petition organizers and signatories, the former approach is no longer defensible. “People feel that continually sending people to Israel will not make change, that we are just aiding and abetting the Israeli government by perpetuating a praxis of aliyah,” said Micaela Beigel, a movement alumna currently writing a Master’s thesis on Habonim Dror at the University of Glasgow. “The Israeli government wants white Jews from the US. The fact that the movement delivers that, even through a critical lens, is becoming unacceptable to dissenters of the movement.” Some dissenters added that the movement’s Israel programs tend to use a less critical lens on Israel/Palestine than the one provided at camp. During her Workshop year, Sher-Kisch said, “in some ways it felt like we were pretending [the occupation] wasn’t happening.”

“The Israeli government wants white Jews from the US. The fact that the movement delivers that, even through a critical lens, is becoming unacceptable to dissenters of the movement.”

Kenneth Bob, a founder of the Habonim Dror Foundation, which raises funds for HDNA, said he supports efforts to revamp and improve the movement’s Israel programs, but rejects “this notion that we shouldn’t have Israel programs,” noting that those advocating this path are “abandoning the fight.” But petition organizers emphasized that they don’t see the petition as a form of full withdrawal from Israel-related issues: According to organizer Noga Shlapobersky, “We see this as meaningful solidarity with our Israeli and Palestinian partners who are fighting for a more just Israel/Palestine.”

SOME HABONIM MEMBERS AND ALUMNI have expressed frustration that the petition organizers abandoned the movement’s internal democratic processes when they went public, and that they brought in the voices of alumni instead of focusing solely on the college-age movement members who should be making decisions. Habos traditionally hash out debates and vote on proposals at a veida, or convention, held every other winter. “I think the organizers recognized this wasn’t something that would be able to be achieved democratically, so there was an attempt to force the issue in an undemocratic way,” said Schwartz, who led the mazkirut artzit when the petition was released.

Petition organizers, however, say that they chose this tactic because the movement’s democratic structures are broken, as evidenced by the fact that years of debates about Zionism at veida have produced little change. The convention is expensive, and attendance tends to be low; it is also run by the Zionist-leaning mazkirut artzit, which vets all proposals before they go to the floor. When major changes are made through democratic structures, it’s up to a group of overworked young people—often concerned about backlash from donors, parents, and Israeli partners—to implement them. In 2015, veida members passed a resolution called “Zionists Against the Occupation,” in which they pledged to boycott all products produced in settlements in the occupied territories. The resolution was so controversial that HDNA leadership excluded it from the official online record of proposals passed at veida, explaining they would wait to make it public until the official launch of their boycott campaign. But, according to Noah Finkelstein, who served on the mazkirut artzit at the time, the resolution was in fact never implemented at all; it fell by the wayside due to the mazkirut artzit’s heavy workload and fears of provoking controversy.

Many of these dynamics were on display in 2019, according to Sher-Kisch, when she and two other movement members introduced a resolution on Zionism at the December veida. Their original proposal called for HDNA to rename the foundational “pillar,” or movement principle, that focuses on Zionism, changing it to “something that signifies our continued commitment to Jewish peoplehood, including those [sic] in the current state of Israel, along with our recognition of the problematic history of Zionism and our desire for a more pluralistic movement culture.” The resolution justified the proposed change by stating that “regardless of our interpretations, we cannot ignore what Zionism has meant materially, for millions of Palestinians . . . To continue to call ourselves Zionist in North America alienates us from ideological partners committed to our collective liberation in the US and Israel/Palestine.” The proposal also called for Habonim to recognize that “Palestinian liberation is more important than the existence of a country with a manufactured 51% Jewish population,” to fight for a binational state with right of return for Palestinians alongside right of aliyah for Jews, and to become a comfortable space for “identifying as Zionist, anti-Zionist, or anything in between.”

After an intense debate, the veida passed a version of the proposal’s first prong, which called for changing the movement’s “Zionism” pillar, but the language was softened to be less decisive. The final resolution mandated that instead of making any changes immediately, Habonim would create a committee to conduct a year-long educational process about Zionism in the movement that would lead to an “emergency veida” at the movement’s winter seminar in 2020. But that emergency veida has not happened yet as the educational process was delayed by Covid-19, according to mazkirut artzit leader Kushner. Notes from the 2019 event obtained by Jewish Currents indicate that the remaining prongs of the proposal never made it to a vote, because the mazkirut artzit abruptly ended the veida earlier than usual. (Schwartz said the decision was not political but an attempt to better accommodate people with disabilities by not going too late into the night.) “I really don’t think it was a conspiratorial effort to destroy our proposal,” said Sher-Kisch. “I just think it’s a structural flaw in the movement that everyone who is in charge of anything or above the age of 26 feels the exact same way about Zionism.”

“I just think it’s a structural flaw in the movement that everyone who is in charge of anything or above the age of 26 feels the exact same way about Zionism.”

Kushner said a leadership priority for the upcoming year is to create more opportunities for movement members to talk to one another, and acknowledged that the movement’s current democratic structures may be insufficient: “We need to talk about anti-Zionism, we need to talk about Zionism, but the ways that we’re talking about it right now haven’t been working out.”

Meanwhile, organizers are continuing to meet and to insist that it’s not just possible but necessary to reinvent HDNA without Labor Zionism at its core. They are especially excited about new programs like Bonimot Tzedek, the program that engages youth in social justice in the diaspora. “Progressive Labor Zionism served as an initial catalyst to [Habonim’s] medium of change-making in the early and mid-1900s, but it doesn’t inform much of the really inspiring work that is currently happening” at Habonim summer camps, Shlapobersky said. Sher-Kisch stressed the continued importance of Habonim’s unique orientation. “In a world that preaches individualism, competition, apathy, and Christian hegemony, camp is a world where we emphasize the opposite. These summer camps provide kids with a truly alternative way to live,” she said.

Regardless of the value that dissenters to Zionism may find in HDNA programming, it remains to be seen how much the organization can change to make space for them. For his part, Kenneth Bob, the Habonim Dror Foundation founder, doesn’t think it makes sense for those who don’t want to affiliate with Labor Zionism to remain in the movement. “A movement gets to have a mission,” he said “If you don’t want to be involved in that anymore, go do something else.”

This article has been updated to reflect the number of seats won by the Labor party in Israel’s March 23rd, 2021 elections, which occurred after the Spring 2021 issue went to press.

Mari Cohen is associate editor at Jewish Currents.