Reform Judaism Needs an Identity Beyond Israel

A major conference proposes to “re-charge” the movement by strengthening ties to the Jewish state, neglecting an opportunity to develop its unique religious vision.

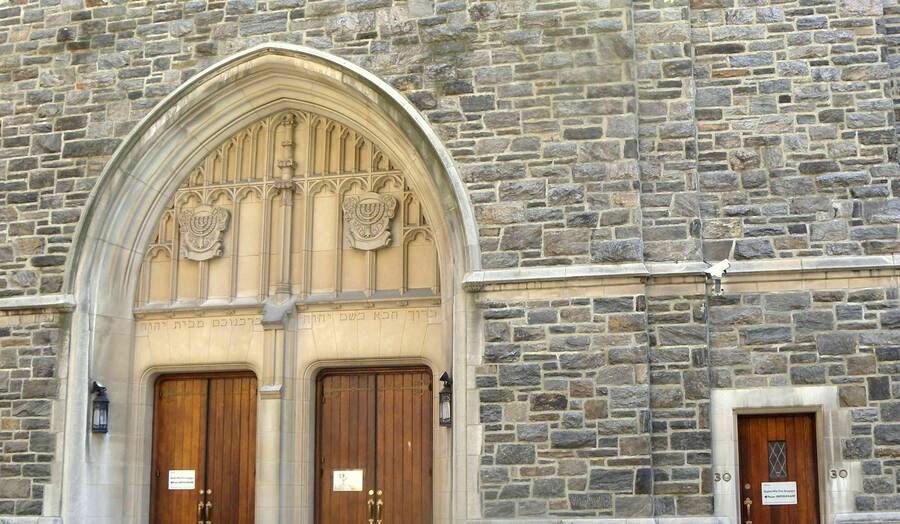

Stephen Wise Free Synagogue in 2011.

This week, rabbis and other leaders of the Reform movement from the United States and Canada will gather at the Stephen Wise Free Synagogue on the Upper West Side for a two-day conference called “Re-Charging Reform Judaism.” The occasion for this event is a crisis in the Reform movement: “In this historic moment of unprecedented change,” the conference’s website proclaims, “the future of North American Reform Judaism hangs in the balance.”

Indeed, according to an article published by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency last year, dues paid by Reform congregations to their parent organization, the Union for Reform Judaism, have dropped by two-thirds since 2007. This decrease in funding, combined with a dramatic decline in enrollment, led the movement to announce last year that the flagship Cincinnati campus of its seminary, the Hebrew Union College—where I was ordained in 1988—will close its doors once the class of 2026 has graduated. Longer-term projections are also bleak. A 2021 study by the Yale School of Management, based on 2013 Pew data, projects that both the Reform and Conservative movements will shrink significantly over the next 50 years, while Orthodoxy will grow. According to this study, the number of Reform and Conservative congregants between the ages of 30 and 69, the prime age range for dues-paying members, will drop by a whopping 46% during that time, likely threatening the viability of non-Orthodox synagogues.

If the future of American Reform Judaism is in peril, it seems the movement should be taking a good hard look at its belief system and asking how it might better speak to the spiritual needs of contemporary Jews. Yet while the “key issues” outlined on the conference’s website include “rooting justice and tikkun olam efforts in Jewish tradition,” “re-centering God and elevating creative ritual practice,” and “prioritizing and funding . . . education,” the very first item of concern listed is not Reform Judaism as such, but “the growing distance between North American Jews and Israel.” In fact, the agenda reveals that a considerable portion of the conference—which is sponsored by the synagogue’s “Amplify Israel” initiative—is devoted to the Jewish state: The subject takes up most of the first day’s proceedings, which include a plenary on “Zionism and Jewish peoplehood” and workshops on “Centering Israel and Zionism in our Sanctuaries and Communities,” “The Components of Healthy Jewish Identity Formation in Relation to Israel,” and “When Anti-Zionism is Antisemitism and its Impact on Reform Jews.” There’s even a half-hour set aside for “Celebrating Israel at 75 Through Song.”

As Rabbi Tracy Kaplowitz, a leader of the conference, told The Times of Israel last year, “the importance of what we’re doing is to ensure that there’s no light between” Reform Judaism and Zionism. This insistence that the movement must be reinvigorated by bolstering its attachment to Israel is the latest step in a decades-long process of Reform Judaism coming to treat Zionism as a spiritual center. What we need instead is to focus on building and articulating the unique religious identity of Reform Judaism itself.

There is an irony to this emphasis on the Reform movement’s relationship to Zionism, considering that American Reform Judaism began in the 19th century in opposition to the concept of a Jewish state. In 1885, a group of rabbis drafted the Pittsburgh Platform, a concise statement of Reform beliefs and ideals, including this axiom: “We consider ourselves no longer a nation, but a religious community, and therefore expect neither a return to Palestine . . . nor the restoration of any of the laws concerning the Jewish state.” This principle was understood as arising from the movement’s conception of Judaism as “a progressive religion, ever striving to be in accord with the postulates of reason.” But in the ensuing decades, the largely culturally assimilated German Jewish society of 1885 America was transformed by an influx of millions of Eastern European Jews fleeing antisemitism. By the advent of World War I, nearly 85% of American Jews were of East European origin. These refugees, some of whom became Reform Jews, brought along a greater sense of separateness from gentile society, reverence for Jewish tradition, and commitment to Jewish peoplehood; some were Zionists. Meanwhile, though there was still significant resistance to Zionism in Reform Jewish circles, a number of prominent Reform rabbis—such as Stephen Wise, the founder and namesake of the shul where the conference is occurring—began to campaign forcefully for a Jewish state.

The change in makeup of American Jewry, as well as concern over the rise of Nazism in a moment when the US had all but shut its doors to immigration, were reflected in the Columbus Platform of 1937, which departed from the Pittsburgh Platform in calling for “the rehabilitation of Palestine” for “many of our brethren” and “affirm[ing] the obligation of all Jewry to aid in its upbuilding as a Jewish homeland.” The cataclysm of the Holocaust and the establishment of the state in 1948 cemented Reform Judaism’s relationship to Israel, and Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War in 1967 intensified this attachment to a messianic extreme. In 1997, the Reform movement codified this theological bond in the Miami Platform, which was dedicated entirely to Zionism. It called upon Reform Jews to study in and visit Israel regularly, encouraged aliyah, and declared that “the renewal and perpetuation of Jewish national life in Eretz Israel is a necessary condition for the realization of the physical and spiritual redemption of the Jewish people and of all humanity.”

For Reform Judaism, identification with Israel has filled the emotional void left by the early movement’s rationalist retreat from religious tradition, providing comfort and certainty. For many centuries, Judaism provided a bedrock belief that the divine will was revealed, word for word, on Mount Sinai; the Reform movement, on the other hand, accepted modern scholars’ understanding of biblical and Talmudic law as having human origins. Rather than truly wrestling with the problem of how to provide a firm spiritual footing without relying on fundamentalist beliefs, Reform Judaism traded one form of fundamentalism for another. The story of the Jewish state—a secular epic to replace a literal belief in the exodus from Egypt—has thus served as a primary locus of religious enthusiasm for Reform Jews, perhaps at the expense of the development of the movement’s own unique spiritual vision.

The notion that the Reform movement should be “re-charged” by strengthening its ties to Israel is especially problematic in light of the Jewish state’s increasing rejection of the progressive values shared by Reform Jews. Last November saw the election of the most right-wing government in Israel’s history, putting in power officials who, among other things, favor replacing Israeli law with the Orthodox Code of Jewish Law and contemplate the outright annexation of the West Bank; the Netanyahu government is already hard at work trying to disempower the judiciary and its potentially moderating influence. But the uncomfortable truth is that, even beyond the decades-long occupation of the West Bank, there has always been an undemocratic side of the state: At its heart, the premise of Zionism—explicitly reaffirmed by Israel’s 2018 “nation-state” law—is that Jews have more of a right to live in Israel than other kinds of people. Considering this ideological misalignment, it’s no surprise that Reform Judaism’s love of Israel has never been mutual. The state does not recognize Reform conversions or marriages performed by Reform rabbis, and while it funds Orthodox institutions, it very rarely supports Reform ones. For the most part, Israel seems to care about Reform Jews—who represent a tiny percentage of Israelis but, for the time being, the majority of American Jews—only insofar as they support the state: The new diaspora minister, Amichai Chikli, has expressed disdain for Reform Judaism, whom he says are “seeking to assimilate and affiliate themselves with groups who are anti-Israel.”

As the organizers of “Re-Charging Reform Judaism” rightly note, while the Reform movement is facing “existential challenges,” it is also a major moment of “opportunity.” But the path forward proposed by this conference—to re-energize it primarily by embracing Israel even more tightly—may be self-destructive. By relying on an increasingly mythical liberal Zionism for survival, Reform Judaism is deferring a reckoning with its fundamental problems, while further alienating the 25% of American Jews, including more than a third of those under 40, who believe that “Israel is an apartheid state,” according to a 2021 survey by the Jewish Electorate Institute. I myself do not pretend to have the answers to what a new Reform ideology and spirituality might look like. But I believe we can begin by looking both outward—making alliances with liberation movements in America and around the world at large, in line with the movement’s progressive principles—and inward, asking ourselves anew the question of how Judaism might take shape in the modern age, without a return to fundamentalism. Zionism will not offer such answers. Only Reform Jews can.

David Regenspan is a retired Reform rabbi with a secular outlook. He has published short stories in, among other places, the Jewish Literary Journal and jewishfiction.net. He lives in Ithaca, New York, with his wife, poet and professor Barbara Regenspan.