WE JEWS LOVE REPETITION. Our prayers are full of it: the Kaddish and Amidah are recited multiple times a day, and the Yom Kippur service centers on the Al Chet’s repeated penance “for the sin which we have committed.” Our culture is no exception. Some of the past years’ most prominently Jewish works—from TV shows Russian Doll and Transparent to the Paula Vogel play Indecent—have centered around the repetition of themes that, while changing in exact form, remain constant across time and space.

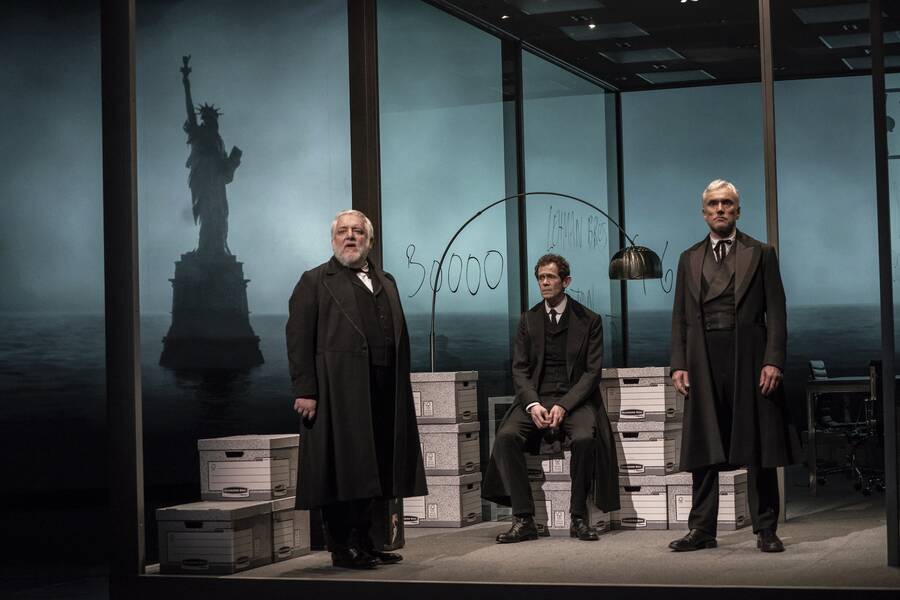

A new play, The Lehman Trilogy—recently opened at New York’s Park Avenue Armory following a sold-out run in London—continues the trend. Adapted from Stefano Massini’s original Italian by Ben Power, The Lehman Trilogy follows the history of the Lehman Brothers investment bank from its humble beginnings as an Alabama dry goods store in the mid-19th century to its infamous collapse at the start of the 2008 financial crisis. But far more than that, director Sam Mendes’s production is a vivid narrative of American capitalism itself. With three actors playing dozens of characters, The Lehman Trilogy urges us to see the story not just of a single family, but of the greater socioeconomic system that they shape, and are shaped by in return. Es Devlin’s set design—a rotating glass cube which stands in for everything from the New York Stock Exchange to a synagogue—emphasizes the universality of the story.

But this tale is also grounded in the particular, leaning heavily on Jewish themes. Their repetition throughout the play shapes the story of a bank—and economic system—in which the sins of the past reverberate through the present. For the story of Lehman Brothers is also the story of the Lehman brothers, Jewish immigrants from Bavaria whose Old World traditions are eroded with each, ever more assimilated, and ever wealthier, generation of the family.

Take the Jewish mourning ritual of shiva, which appears in each of the play’s three acts. In the first we see the death of the eldest Lehman, Henry, observed by his youngest brothers according to the full traditions of their forebears back in Europe, as the show’s trio of actor-narrators tell us. The Kaddish is read, the suits are torn, and the Lehman shop is closed for the full seven days. Yet by the second act, when the store in Alabama has become a New York bank, the next brother Emmanuel’s passing yields only a three day shiva. When his son Philip dies in 1947, the now full-fledged investment firm—led by a Lehman more comfortable in Hotchkiss and Yale than shul—only observes a token three-minute closure. This time, the narrators assure us, no suits are torn.

This narrative comes as little surprise to an audience likely familiar with the classic fables of immigrant assimilation and the loss of old traditions. Indeed, this matches the experience of my own American Jewish family over the past century. But The Lehman Trilogy adds a twist, using the typical Jewish immigrant experience to talk not only about generational conflict over assimilation, but about capitalism.

Like the shiva, capitalism is assiduously observed by the Lehmans from their first days in America. The enterprising Henry makes his first real profit when he sees an opportunity to sell cotton seed to plantation owners after a fire takes the last harvest. The planters will pay him back directly with a share of the crop, which the Lehmans then sell to textile mill owners. A handsome profit is made for the Lehmans on the backs of slaves.

Also like the shiva, the nature of American capitalism changes over time. Once the Lehmans are resettled in New York, they move from cotton into industry, investing in the great east-west railroads of the late 19th century. And by the roaring ’20s they have pivoted into abstract finance, direct investment giving way to stock shares.

But even as the engine of the Lehmans’—and America’s—wealth changes, the indifference to those whose labor actually creates this bounty remains. Greed at the cost of humanity is the greatest inheritance passed from each generation to the next. It’s no coincidence that the one Lehman who takes a moral stand—the New Dealer Governor of New York, Herbert Lehman—is also the only one to leave the family firm.

It’s not only shiva that repeats throughout the play. Each generation of Lehmans is also plagued with a terrifying nightmare of greed and moral decay. For Emmanuel, it is a train plowing into him; for his grandson Robert, it is the tower of Babel, rendered in briefcases. As in the Bible, the prophetic tradition passes from generation to generation, and like the Jewish people, the Lehmans fail to heed these admonitions.

Death and wealth; Judaism and capitalism; diaspora and slavery—The Lehman Trilogy is ambitious in connecting themes in a manner that many American Jews may find uncomfortable, even offensive. Indeed, Massini—who is himself Jewish—seems to borrow from the Yiddish playwright Sholem Asch, who portrayed a greedy, unscrupulous Jewish patriarch in his seminal God of Vengeance. For Asch as for Massini, there was value to internal critique of Jews who went against the ethical values of tradition.

The Lehman Trilogy does this expertly, putting the Lehmans’ Jewishness and capitalist excess in tension. The play’s third and final act is titled “The Immortal,” referring not to a disintegrating Jewish identity nor to the Lehman family itself, which by the 1970s has lost control of the bank, but to profit—the mammon that both bank and country serve continuously, from the plays first scenes to its last. Judaism comes and goes, but capital is eternal.

Massini’s critique of capitalism does not come with clear answers on how to defeat it. But the play does offer a hint to where those answers may lie. Echoing in my mind as I left the theater was the idea of teshuva: repentance, but more literally, “return.” The Lehman Trilogy, by constantly reminding us of the sacred rituals the titular family has abandoned, urges American Jews to return to our traditions: to the Judaism of the Prophets who warned against idol worship and obeying false kings; the Judaism of the immigrant workers who challenged the capitalist excess the play’s subjects espoused. In coming back to this great inheritance, American Jews today may find the tools for dismantling the systems of oppression the Lehmans helped build.

Aaron Freedman is a writer based in Brooklyn, NY.