Point of No Return

Palestinians cannot turn back the hands of time. But we might still imagine a world beyond exile.

The evening before Dido’s funeral my father tells me, for the first time, the origin of my middle name. Faris. When he was a teenager training with the PLO in Lebanon, everyone had a nom de guerre, and his was Abu Faris. It’s hard for me now to imagine my father caught up in the revolutionary romance of the late 1970s, but there he was: absent-minded, bookish, militant, father of a knight. And here I am, Faris—his return.

The bourne of return animated my father and his eldest brother differently. While my father, Ziad, was struggling in Lebanon against the Zionist forces responsible for his exile, Zahi was taking every opportunity to go back to the land. In November 1982, when Israel invaded Lebanon and occupied the south of the country, the border was briefly opened and Zahi went back again, crisscrossing historic Palestine in taxis and buses to return home to Gaza. In spite of Dido’s warnings, he spoke to the Israelis he encountered, soldiers and civilians alike, eager to pierce the political divide with human connection.

Despite the best efforts of Ziad and his comrades, the PLO failed to unseat Israeli sovereignty.

No matter how many times Zahi crossed Palestine, the stitches would not hold.

Now Dido lies, finally, at the Shore Point Funeral Home in Hazlet, New Jersey. I am here, too, holding my father’s story and Zahi’s, and holding my own return as well—a knight 50 years late for battle in armor that doesn’t fit. Though my parents have long been divorced, my mother has also come to pay her respects. She brings with her the recent loss of her own father and her own narrative of exile—the Jewish story, from 2,000 years ago. The ornate and sterile room in the funeral home tucked off the side of State Route 35 feels like a set that has been conjured by our gathering for the moment only and will fade to dust immediately upon our exit. An exile’s death.

We have each come bearing our pretty narrative conceits. Ziad, The One Who Fights and Defeats No One, kisses his father on the top of his head before the casket is closed. Zahi, The One Who Goes Back and Convinces No One, addresses the gathered mourners with eulogies collected from the diaspora. I, The One Who Writes to No One, sit silently, holding tightly to my grandmother Teta Lillian’s hand. And, at rest inside a delicately carved wooden casket, lies The One Who Knows He Will Never Return.

What is a story for? Perhaps it is to fix in language a memory of what has been lost. My family’s stories all bear witness to distance, to absence. Narrative sets this loss squarely in the past, behind our present—the future awaiting us, further still from the events of the tale. A story is a line, the most efficient route from here to there.

When I sit with my family around the kitchen table, this is what I am told: First we were forced to flee Jerusalem. Eleven of us squeezed into the car with some clothes and two blankets (“Don’t worry about your toys, we’ll be back in a week”), and then we were on the road from Jerusalem to Al-Khalil to Bir Seb’a and finally to Gaza. We brought the keys with us. But then we were exiles; when we tried to return, we couldn’t, or it was gone. Inshallah in the future we will return, or if not me, then perhaps you.

The past is fixed and the future has not yet come, but we are drawn toward it; the dark precursor of return pulls us forward. It is a singular past, the moment before diaspora transposed and dimly projected forward through time. The problem with a finite line, though, is that it concludes in a single point.

What sense does this single point of “return” make for a diaspora—a people scattered around the globe who gather around kitchen tables and remember in language what we’ve lost?

What sense does this single point make for a diaspora—a people scattered around the globe who gather around kitchen tables and remember in language what we’ve lost, the stories binding us to each other as much as to the land recalled by our elders? We are, by now, irreversibly fractured. Though we can trace our exile back to a single origin, generations of differentiation across land and circumstance create a whole that does not fit neatly back together. What kinship do I have with the Palestinians still trapped in refugee camps—the trauma of dispossession not an intergenerational memory but a daily occurrence—if I struggle to comprehend my aunts and uncles speaking their native tongue?

Dido always called me by the name I called him. This doubling, common in Arabic, confused me as a child, but if I ever protested (“I’m not Dido, you’re Dido!”) he would just laugh. It was only as he was dying that I think I finally understood: Neither of us is Dido. Dido sets us in relation to each other. It describes a distance: genealogically, cartographically. We are two points on a map, measured not along a flat plane but through tight folds and across the gaps formed by a crumpled surface.

Politics—like narrative—has a way of charting these distances according to a single measurement. Return: the reversal of diaspora, the restoration of what was lost, a doubling back so as to bring all distances to zero. But the harm of dispossession is transformed in the movement between generations. We can visit, kick rocks across the surface of the dusty road, squint up at the desert sun, drive past the cemeteries, through the hills separating Ramallah from Bethlehem, gold and tan speckled with white buildings—but the smells and sounds spark memories that are not our own. For the diaspora, Palestine exists in the mind.

Both sides of my father’s family are from Gaza. Sometime in the interwar period, each had made a short migration east. Dido Saba, my father’s father, was born in Jerusalem, and Teta Lillian, my father’s mother, in Haifa. The Nakba sent both back to Gaza—Dido by land and Teta by sea. They met there, exiles in their homeland. In 1967, the war forced them to make another exit—this time to Qatar, where Dido had taken a job as an assistant to the emir. A palace coup in 1972 would send the family to Beirut, where they finally settled.

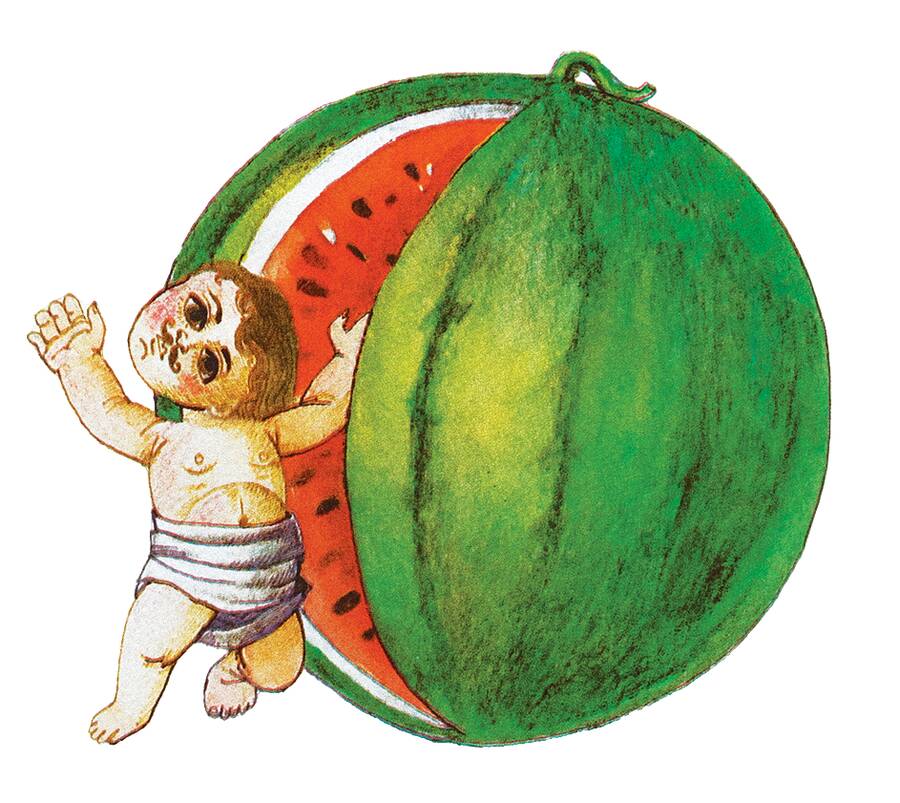

For those who remained in Gaza, including the members of my family who were not evacuated, the 1967 invasion marked the start of Israeli occupation. The military annexed the territory, initiating a decades-long program of settlement and brutal colonial rule designed to make the densely populated region so unlivable that Palestinians would choose to flee. Expressions of Palestinian nationalism were forbidden. In 1980, the story goes, the Israeli military shut down an exhibition of works by Sliman Mansour, Nabil Anani, and Issam Badr at Gallery 79 in Ramallah only three hours after it had opened. The artists were summoned by military officers who disciplined them for painting the Palestinian flag. “Make flowers instead,” they were told. Badr faced the officer: “What if I were to make a flower of red, green, black, and white?” The officer replied angrily, “It will be confiscated. Even if you paint a watermelon, it will be confiscated.” In recent years, Palestinians have begun to display sliced watermelons—their national pride reflected in green skin, white rind, black seeds, and red flesh.

The family did not see Gaza again until 1974, when they returned to visit relatives for one month during the summer. During a summer trip the following year, the civil war in Lebanon that had broken out in April escalated, and they decided it was safer to stay.

Sometime over that summer of 1975, my grandfather asked Zahi, then 15, to go with his cousin to pick up some falafel from the local shop. It was less than a ten-minute walk from their home, but to get there they had to pass the jawazat, an office where Israeli occupying forces processed identity documents. A guard tower bordered the administrative building, with two soldiers stationed on top. As Zahi and his cousin passed, one of the soldiers called out to them in Arabic, but the boys kept moving, pretending not to hear. When they returned by the same route, the soldier stood blocking the road.

“Why didn’t you stop when I told you to stop?”

“My parents tell me not to talk to strangers.”

The soldier noted Zahi’s accent—eight years in Beirut had revised his Arabic—and asked where he was from. Zahi explained that he lived in Lebanon and was visiting family in Gaza for the summer. The soldier asked him when he left. Zahi told him ’67.

“You must be impressed by the progress that we Israelis have made in Gaza. Look at the asphalted roads, the beautiful tiling, the halogen lamps illuminating the streets. I’m sure you appreciate what we’ve done?”

“This means nothing to me,” my uncle responded. “If we are under occupation, whatever you do as occupiers, it means nothing.”

The soldier, somewhat amused: “You Arabs always refuse to benefit from the opportunities given to you. Do you know your history? Take the 1947 Partition Plan. You rejected it and gave up the chance for an independent country.”

Zahi thought for a moment. “You know, from the Torah, the story of Solomon’s Judgment?”

The soldier knew the story, but my uncle told it anyway. Two mothers came to Solomon, King of Jerusalem, with an infant baby. Both women claimed the baby as their own and sought Solomon’s judgment in resolving the dispute. The king called for his sword and announced that he would split the baby in two so that each mother could keep half. One of the women called out in protest and revoked her claim, saying the other should have the child. Solomon, in his wisdom, deemed her the true mother—the one who was willing to give up her child rather than see him split in two.

By this point Zahi’s cousin was pulling hard on his sleeve, pleading with him to leave. The falafel was cold, and his uncle, my grandfather, would

be upset.

They turned away from the soldier and headed home.

In the summer of 2012, shortly after my 19th birthday, I made my own way to Palestine. I wanted to feel a sense of origin, and I wanted that connection to make me whole. But this desire was smothered by the ongoing processes of dispossession in Palestine: I bore witness to the demolition of homes in the West Bank, the humiliation of laborers crossing checkpoints, the settler assaults on Palestinian school children—the grim reality of occupation was too immediate for me to feel much of anything but dread. When I came to visit as a child at the turn of the millennium I was able to move freely between Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip, where my extended family still lives. But by 2012 prison walls had been built around Gaza, cutting it off from the world. I could no longer touch the land where my entire patrilineal ancestry was born. Instead, I walked the cobbled streets of occupied Bethlehem and snapped a photo of a middle-aged man in a flowing, white thobe—blinding in the unslanted desert sun, pristine and undifferentiated save for a jet-black iqal, like the shadow of a halo—pressing his hand up against the stone wall beneath the poster of a martyr. I told myself it was his son so that I would cry.

After several weeks in the West Bank, I decided to travel across the Green Line, and made my way from Jerusalem down past Hebron and through to the Negev via a discontinuous series of buses, taxis, and cars. At the time, I didn’t know that Dido had fled back to Gaza with his family in 1948 by a similar route. When he told the story late in his life, it was punctuated by long, belabored pauses as he pained himself to remember. “He never used to mention that their car was shot at leaving Jerusalem,” my aunt said.

I spent the night in a Bedouin village with some friends of friends who told me about the ritual demolitions. Israel did not recognize that village, like many others, and cut it off from basic services. Every several years, I was told, they demolished the homes and other semipermanent structures. I nodded curtly, embarrassed to be a tourist.

I had made a habit of looking all soldiers directly in the face. We were often the same age and I wanted them to see me, too—to see how I was seeing them.

A couple of days later, I stood on the platform at the station in Tel Aviv, waiting to board a train headed to Haifa, when a particular Israeli soldier caught my eye. I had made a habit of looking all soldiers directly in the face. We were often the same age and I wanted them to see me, too—to see how I was seeing them. But this encounter was different. The soldier’s deep brow, furrowed in the summer heat, and piercing hollow eyes shocked me; I felt it immediately in my stomach—a weightlessness dissipating and then reforming the outline of a face, his face, a face I know.

As a kid, I saw everything to do with my family’s stories, habits, and traditions as expressions of the individuals I associated them with—not characteristics of some larger group. But then I met Joshua. Early in elementary school, we had gotten along well and would often read together at recess. He showed me that these traits I had understood as personal and idiosyncratic are, in fact, expressions of history which have psychological significance for the individual and social meaning for the group. He was so incisively clear that Judaism is a particular identity, something that you either are or are not. And since my mother is Jewish, I felt the amorphous, unbordered conception I had of myself stiffen toward definition: I am a this and not a that. I felt included. For me, it was a tenuous, sensitive identification, and one I moved to abandon as a young teenager, when I came to realize that the acute dispossession and exile of my Palestinian side had a much stronger grip on my political psyche than did the comparatively attenuated kinships of “being Jewish”—despite my mother’s best efforts to explicitly connect her own radical politics to Jewish identity. Unconvinced and irreligious, I denied being Jewish at all.

But, for Joshua, these borders were paramount. When our second grade teacher announced in front of the class that Joshua, who was adopted by an Ashkenazi family, was from Iran, he denied it. The confrontation was forceful and awkward. As we got older, in fourth and then fifth grade, I saw his lines of demarcation become more intense, more compulsively drawn. He got in trouble for carving a swastika into a bench in the playground. He would sometimes carve even into his own skin, a classmate’s initials, an act of devotion to his crush. He surrounded himself with his anger.

And then there he was, standing on the train platform in full military uniform, deep brow, hollow eyes, rifle strapped across his chest. He saw me as I saw him, and for a moment his eyes were no longer hollow. We sat together on the train. I asked him about his life. He was painfully candid about his quotidian miseries. He told me about sleeping on stone, eating canned tuna for every meal, how he didn’t know why he was there, how he was depressed and thought every day of dropping out of the IDF, of leaving, and how shame kept him firmly rooted in place. I don’t know if he assumed I was there “as a Jew” or “as a Palestinian,” or what he even recalled about my background. I didn’t respond. I thought about how shame should make him leave, about the black hole of his ego, about my disgust and my pity. And then I got off the train.

“To return to our land” is a rallying cry for both Zionists and Palestinians. And yet, there is no moral equivalence between these claims. Zionists seek to annihilate the present and its attendant histories in order to “restore” a mythic past. In this regard, their vision of return is necessarily violent and dispossessive. I saw it enacted in the demolitions, and in Joshua’s anger. The Palestinian call for return, by contrast, can be liberatory. But this will require a different relationship with time: a commitment not only to undoing the world as it is, but to remaking it as it should be.

The Palestinian call for return can be liberatory. But this will require a different relationship with time: a commitment not only to undoing the world as it is, but to remaking it as it should be.

There is, of course, no Solomon the Wise; Jerusalem has no king. But there is the sword, and Palestine bears the scars of division. Walls, checkpoints, settlements, and the roads that connect them carve up the land, splitting villages and families. A military system of surveillance and detention regulates a colonized population through terror. Upon their chimerical return, this is what the exile finds.

The family returns to my grandfather’s Jerusalem home in 1974 but does not go inside. Dido refuses to come along.

The family returns to my grandmother’s Haifa home in 1975 but does not go inside. Teta refuses to knock on the door: “There are Israelis in there now.”

Joshua, too, draws maps, seeking the origin of exile: He carves in his body the initials of the woman who rejects him, carves in the bench a symbol of ultimate dispossession.

That both Zionist and Palestinian calls to return hinge on land does not mean, as it is sometimes framed, that two peoples are simply fighting over a particular terrain. Like return, a shared lexicon with divergent meanings, land, too, encompasses contradictory philosophies—surfacing as both an object of colonial domination and a critical component of decolonial movements. We say “land,” but mostly we mean “territory.” Land is the physical world—the wild, unbordered field of nonhuman intelligences—and territory the virtual space we make and remake upon it, passively through habit and actively through enclosure.

The destruction inherent in territories is clear. “Why is all geography irony?” the poet Dionne Brand asks. The answer: It is harm, not wholeness, that all borders encircle. Territories are made through dispossession, not destroyed by it. The carving up of land and expropriation of its inhabitants creates the categories of identity that national borders enshrine. Such territories are formed on land, but also in the mind. They both reflect and construct the identities of those developing and maintaining them; they are, in a sense, identities projected onto land. And precisely because they are fictive constructs masquerading as natural and inevitable realities, territories require constant reiteration. Joshua and I both attempt our return chasing a narrative conclusion, to complete ourselves and the story. But the origin proves illusive, and we only learn to retell the tale of exile over again. Joshua doesn’t find the source of his exile in Israel. He finds only a bigger sword, a bigger bench to carve, a map that holds him within its borders but leads him nowhere. I uncover no origins, only a nebulous indignation that hardens into political conviction. There is no full being within, no immutable wholeness to return to or liberate, no knowledge that can restore severed kin.

What we find instead of wholeness is the colony: the territorializing process of colonial dispossession, with its despotic rubrics of self-justification and mechanisms of social enforcement. But it would be a mistake to assume that this territorializing process is unique to the colonial world. Even if we could return to a precolonial relationship with the land, that relationship was itself never pure. The precolonial world was a territory; the postcolonial world will be, too. Worldmaking is a territorializing process. Thus, if Palestinian return is to imbue a fractured people with a worthy national purpose, it cannot be merely a backward-facing act of restoration, but must instead face forward, toward a just world—its shape suggested by the imperative to obliterate Zionism’s legal and social mechanisms of colonial oppression, its logics of containment, and its engineered demographic imbalances. It will mean rooting our inevitable process of territorializing not in essence (I am from here, this is holy land, this land is mine), but in relation (this is where we eat, this is where we pray, on these roads we traverse the desert).

What might it mean to dream of return not as the crossing of space or, impossibly, the turning back of time, but as a metric of relation—the distance between things as they are and as they could be, between a present of borders and checkpoints and a future where we might be together? The colonial system of walls, roads, passports, and decrees does not constitute the ownership of land itself—a brutal fiction—but is instead a system of control overlaid atop it. Land cannot be passed from one colonially defined population to another by revolutionary fiat. Land cannot be returned by transfer. But the exile can return to the land, as the body returns to it in death, ready to deterritorialize themselves and the colony, to destroy the borders inscribing mind and body. Only then might a new territory form, built from relations of care and not hierarchies of control. May we return, then, to the origin of no origins not to solve the problem of exile but to destroy it for good.

In early 1976, Zahi was still in Gaza. While the civil war was escalating in Lebanon, the family enrolled the kids in the local schools. One leisurely Saturday, Zahi and his uncle, only five years his elder, decided to take a taxi to Tel Aviv, where they went to the cinema and then picked up falafel sandwiches, Israeli style, with a little piece of fried fish on top. In the afternoon, on the way back to the taxi stand, they passed through Shuk ha’Carmel, a bustling open-air market in the south of the city where people bought and sold fresh fruits and vegetables, spices, and other wares.

As they were wandering through the stalls, my uncle heard a voice: “Lebanoni! Lebanoni!” Zahi looked around, and saw a fruit vendor calling out to him from the far side of the market. Zahi walked over to him. As he approached the stall, he realized that he recognized the man; it was the soldier from the jawazat, now dressed in civilian clothes, selling watermelons.

“You’re the boy in Gaza, who told the story of Solomon the Wise.”

The soldier-vendor picked out a huge, bright green watermelon and insisted that the boys take it home.

The watermelon. I remember it was heavy and that I couldn’t really think of taking it all the way back to Gaza, especially with a taxi that would usually have up to seven passengers in it. I must have left it somewhere, maybe on the side of the road. I don’t remember giving it to somebody. Most likely, I would have left it in the parking area where the taxis go to Gaza. I just left it by the side. That’s most likely what happened to be honest with you. I don’t really remember what happened with the watermelon except for the fact that it was big and that I had made the decision that it could not be accommodated in that narrow taxi that we would be using to go back to Gaza.

Dylan Saba is a civil rights attorney and writer based in New York City, and a contributing editor at Jewish Currents.