Newsletter

Nov

16

2022

In working on our recent Soviet issue—and particularly the package on the Soviet Jewry movement, which attempted a “second draft of history” about a movement that changed the face of global Jewry—we encountered a curious phenomenon: It was difficult to tell the diverse stories of Soviet Jewish immigrants to the United States and Israel—their experiences in the Soviet Union; their reasons for leaving; their complex social, political, and national allegiances—at a distance of several decades, as much of the nuance in their stories had been supplanted by a unifying, hegemonic mythos. Historian Olesya Shayduk-Immerman wrote convincingly of the ways that the first interviewers of new émigrés, representatives of Israeli and Jewish American organizations, often asked leading questions—and struck from the record anything that diverged from a simplistic, often nationalistic narrative of salvation from Communism and antisemitism by Israel and the American Jewish diaspora. In time, many of the émigrés themselves adopted this narrative, but Shayduk-Immerman found that asking different questions, as she did, produced far more varied accounts. “When we hear only the parts of narratives that confirm the dominant discourse and not the parts that contradict it, we end up with a distorted version of the historical record that reinforces the ideological status quo,” she writes.

At the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine this year, tens of thousands of Ukrainians—many of whom are not Jewish—fled to Israel, as did similar numbers of Russians fleeing Vladimir Putin’s increasingly authoritarian regime. In the images of Ukrainians and Russians being greeted with Israeli flags as they descended from their planes, we saw history repeating itself before our eyes. We heard reports of the Israeli state shunting new immigrants to portable structures in West Bank settlements. We wanted to hear from these people, in their own words, before their stories were buried beneath the triumphant, nationalist lore.

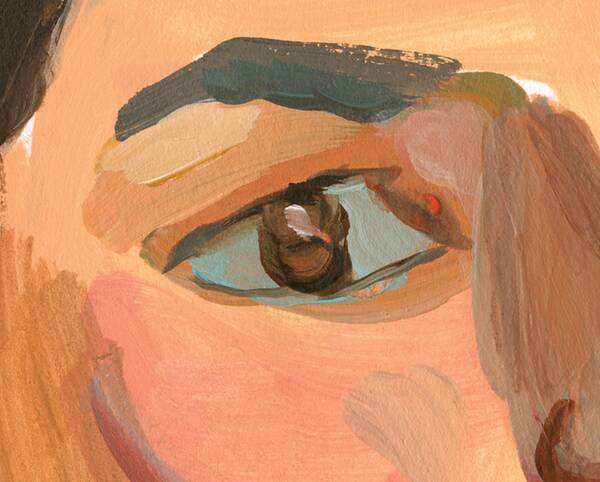

To this end, we reached out to Israeli artist Anna Lukashevsky, a Lithuanian-born portrait painter and a member of the Israeli post-Soviet art group New Barbizon (Zoya Cherkassky-Nnadi, profiled in our Soviet issue, is also a member). Lukashevsky produced seven portraits of new immigrants—six Ukrainian refugees and one Russian dissident—as she interviewed them about their experiences. These accounts, which have been translated and edited by David Klion and Hilah Kohen, appear here alongside the portraits. The subjects—while displaying very different orientations to Jewishness, to Ukraine, and to Israel—universally feel suspended between nationalisms, trying to locate themselves in a dramatically unstable time. I feel as I read them that I can hear their voices as they discuss their abandonment by the Israeli state; their struggles in a new language; their disorientation at being dropped into someone else’s conflict while still processing the one they left behind. I feel that Lukashevsky, with her careful, empathetic looking and listening, has done something truly remarkable with this piece of documentary art. Many will attempt to speak for the refugees in the coming years; here they speak for themselves.

– Arielle Angel, editor-in-chief