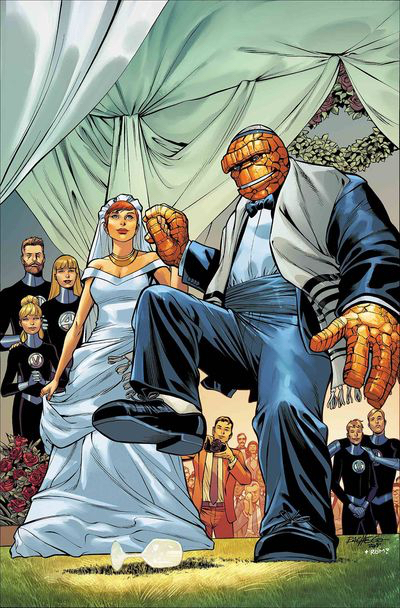

THIS WEEK, the Thing got married. The bride was sculptor Alicia Masters. Her husband, Ben Grimm, aka “the Thing,” is a founding member of the superhero team The Fantastic Four, notable for having been transformed by cosmic rays into a towering, incredibly strong creature with a nearly indestructible orange, rock-skinned body. The couple has been together, depending on how you measure Marvel time, for a few, or perhaps 56, years.

Theirs was, as a New York Times wedding announcement might phrase it, “an unlikely path to romance.” They met in Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s November 1962 issue of The Fantastic Four, “The Lady and the Monster.” Alicia’s supervillain stepfather, the Puppet Master, sought to mind-control the Thing and have him attack his teammates. Alicia Masters didn’t want to do this to the Thing, but her stepfather . . . well, anyway, Masters and Grimm met.

What may not have been so obvious to all readers in 1962, but was prominent at the wedding, is that Ben Grimm is Jewish. Back in the 1960s, the religions of comic book characters were rarely, if ever, mentioned. In an industry and an era where Stanley Lieber became Stan Lee and Jacob Kurtzberg became Jack Kirby, their decision not to mention the Thing’s religion is not surprising. Both lived in a time of openly antisemitic discrimination and exclusion. Marvel only made Grimm’s religion public in 2002. During Kirby’s run on the book, 1961-1971, you can read any Fantastic Four story and never see any trace of it. And yet, for over 40 years, it hid in plain sight.

In the Lee-Kirby collaboration, Lee provided his signature pop sensibility and glib humor, but there’s no question that Kirby was the driving creative force of the team. And of any Marvel character, Ben Grimm is his most directly autobiographical.

Kirby and Grimm were both born on the Lower East Side of New York and grew up poor; Kirby on Delancey Street, Grimm on fictional Yancy Street. Benjamin Jacob Grimm takes his first and middle name from Kirby’s father and Kirby’s real first name, respectively. Kirby and Grimm both fought in World War II and came home moody and prone to fits of anger. After the war, Kirby co-created the most impressive line of superheroes in comics history. Ben Grimm took a different career path, to say the least. In The Fantastic Four’s debut issue, he reluctantly agrees to pilot his best friend Reed Richards’ experimental rocket through a cosmic ray storm, at the goading of Sue Storm, Richards’ blonde, blue-eyed fiancée, with whom Grimm is also in love (“I–I never thought you would turn into a coward!”). Richards brings Storm along, as well as her snarky teenage brother, Johnny Storm.

Grimm was right; Richards blew it. The cosmic rays permanently mutated Richards into Mr. Fantastic, who can stretch his body into any shape; Sue Storm into the Invisible Girl, who can become invisible and create force fields; and Johnny Storm into the Human Torch, whose body can burst into flame at will, allowing him to fly and throw fire. Of the four elements, they were water, air, and fire.

Using the fourth element, earth, Kirby had a different fate in mind for Ben Grimm. His Jewish superhero doesn’t get a glamorous controllable power he can turn on and off; he is completely transformed, trapped in a giant, orange, rock-skinned body, a monster-hero. “He’s turned into—a—some sort of thing!” says Sue Storm on first seeing him. A golem, to be sure, though the word never appears. Instead, Grimm takes his new name from Storm’s stinging repulsion to his new body. The Thing’s brutish, rocklike appearance terrifies people; he is isolated and alienated from mainstream society by a body that is often hated on sight. With Grimm’s Jewishness now public, much of The Fantastic Four has a new context.

IN 2016, Michael Tisserand published Krazy: George Herriman, a Life in Black and White, the first full biography of cartoonist George Herriman, creator of the seminal comic strip Krazy Kat. Thirty years after Herriman’s death in 1944, two researchers independently requested Herriman’s birth certificate from the city of New Orleans. The birth certificate made clear that Herriman was Creole, and had apparently passed for white almost his entire life. Knowing that a person of color created what is widely regarded as the greatest comic strip of all time demanded a reexamination of the entire run of the strip, from 1912-1944. So, too, with Kirby and Ben Grimm.

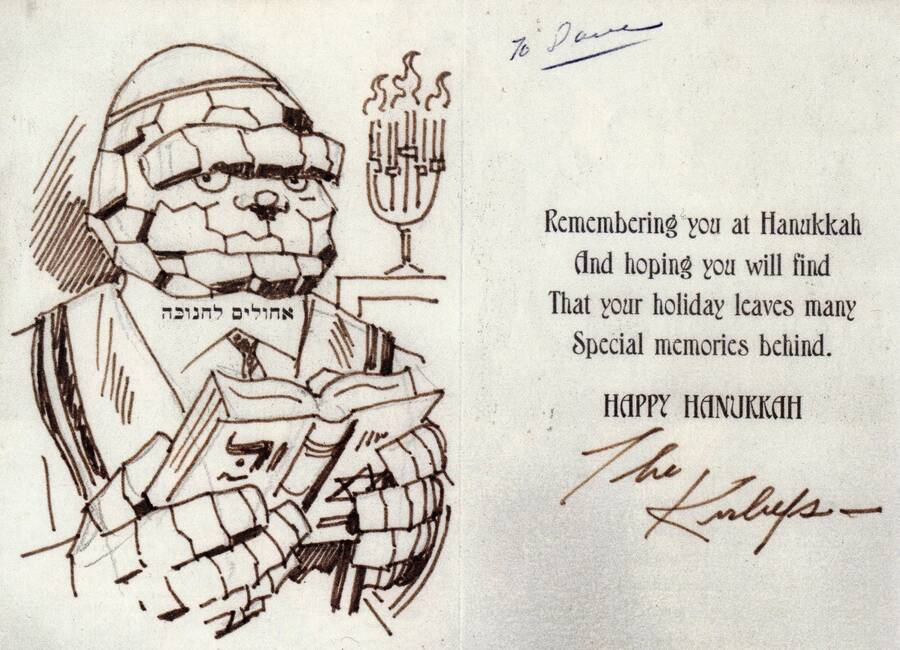

The first known, semi-public acknowledgment of Grimm’s religion was a 1976 Hanukkah card sent out by the Kirby family featuring Grimm in his tallis and yarmulke. In 2002, Marvel made it public with a storyline in which Grimm revisits Yancy Street and his childhood mentor Hiram Sheckerburg on what he thinks is Yom Kippur (Sheckerberg scolds him for getting the date wrong). Thus begins a long conversation about Grimm’s past, and his guilt about leaving the old neighborhood behind for a college football scholarship. The Thing then defends Scheckerberg’s store from Powderkeg, a low-rent supervillain demanding protection money.

The Fantastic Four’s unique quality in 1961 was that, unlike other superhero teams who behaved like friends in like-minded pursuit of justice and villain punching, this was more like a family, one that fought with each other as much as they did skrulls or mole men. Looking back, Grimm’s sometimes moody isolation from his waspy teammates has no end of complications. First, there’s the class difference between Grimm, a Lower East Side street kid, and the wealthy Long Island suburbanite Storms. There’s Grimm’s resentment of Sue Storm choosing Reed Richards over him, not to mention Richards’ miscalculation, which turned Grimm into the Thing. And there’s Sue’s kid brother, a smug rich kid who revels in the girls and celebrity that his superpowers bring him, without a shred of self-awareness or humility regarding Grimm’s fate. Life is just easier for them, and they don’t always understand this, or how much of an outsider Grimm feels like in their world. “Fate has been good to us, Ben! We’ve been able to use our powers to help mankind . . . to fight injustice and evil!” says Richards, full of platitudes. “Sure!” says Ben. “It’s been great for you! But what about me! I’m just a walkin’ fright! An ugly, gruesome thing!”

Grimm’s isolation and assimilation issues are not just limited to his teammates, as he made clear when he explained his long silence about his religion. There’s also antisemitism. “Anyone on the Internet can find out if they want,” he told his Yancy Street mentor Hiram Sheckerburg. “It’s just . . . I don’t talk it up, is all. Figure there’s enough trouble in this world without people thinkin’ Jews are all monsters like me.”

Today, the Jewish life Kirby imagined for Ben Grimm is his life. Grimm’s belated bar mitzvah took place in a 2006 story, “Last Hand,” with Reed, Sue, and Johnny sitting in the front row in their blue Fantastic Four uniforms. This might seem inappropriate at temple, and on such an important day, but given Dr. Doom’s brutal attack at Reed and Sue’s wedding, better safe than sorry.

Ben Schwartz lives in Los Angeles, CA. He has written for The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, David Letterman, Billy Crystal, and is a 2017 NEH Public Scholar grant fellow.