Hope Wrapped in Barbed Wire

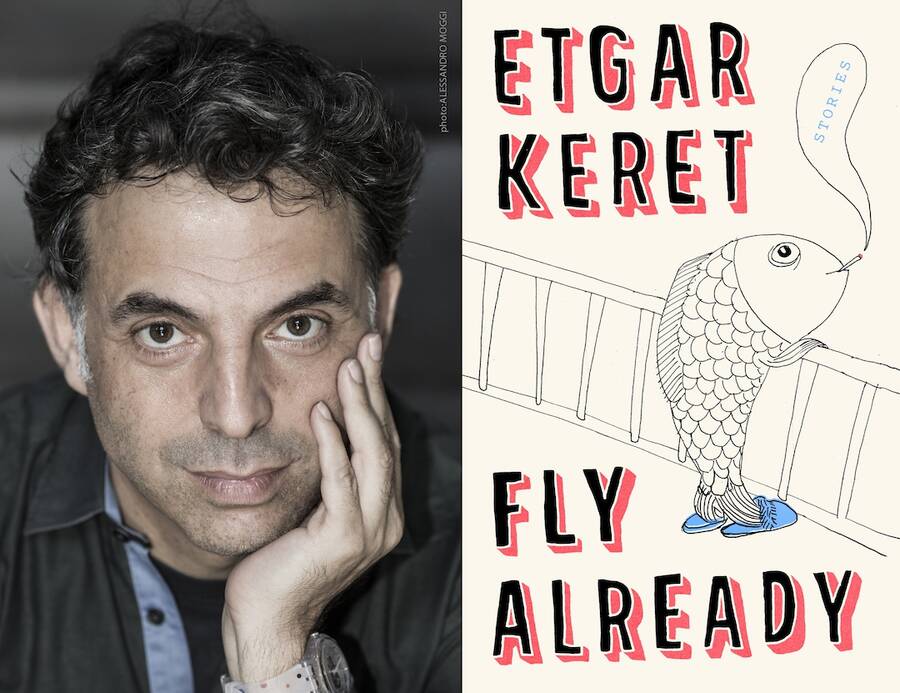

Israeli author Etgar Keret discusses translation, mixing pathos with humor, and his new book of short stories, Fly Already.

Etgar Keret is the author of seven short story collections and the memoir The Seven Good Years. His new collection, Fly Already, out now in English—the original Hebrew edition won Israel’s prestigious Sapir Prize earlier this year—is another book of biting stories about characters in Israel and the United States doing their best not to mess up their lives and the lives of those around them. Keret’s writing finds the pathos and humor in their often futile attempts to keep everything together—as well as the beauty in their efforts.

Keret and I spoke on the phone about his new collection.

Bradley Babendir: What’s your relationship to the process of translating your work, and to your translators?

Etgar Keret: My position is totally passive. They can ask me questions like: “Did you mean, in these stories, that he actually does this?” Or, if a word has a double meaning: “Did you intend this meaning or the other?” But beyond this, it’s really up to the translators.

What you learn the most from the process is that languages cannot perform in the same ways. English is the only language where I really see this, because I speak it. Sometimes I find that a sentence works better in translation than in the original Hebrew. But it also took me some time to accept that my story in English will never be like my story in Hebrew.

For example, in Hebrew we don’t have the pronoun “it,” because all Hebrew nouns have grammatical genders. I have a story in which a woman who discovered that her husband cheated on her goes with a real estate agent to find an apartment for herself, and on the way, the real estate agent comes to understand that she picked him because he rented the love nest to her husband and his lover. As the wife is trying to find an apartment, she’s also trying to get some information about her husband’s lover. At some point, in the Hebrew original, she asks the real estate agent, “Is she beautiful?”—meaning the lover. And he says, “Not only is she beautiful, but you’ll also have your own parking.” Because in Hebrew, the word “apartment” is feminine. So you cannot really translate this ambiguity—this misunderstanding—into English, you can only rewrite it.

A good translator often basically rewrites your story, or reinvents it. My mother is originally from Poland, and she swears that the Polish translations of my books are better than the Hebrew original. I believe her, because my Polish translator, Agnieszka Maciejowska, is a very aggressive and very deep kind of person. She’s a writer, too, and I can see that when she translates me, it goes into Polish with her sensibilities mixed in. I can totally imagine that it works better.

BB: There’s a moment in the story “Pineapple Crush” when the narrator observes a child sitting on top of another, striking him. The English reads, “He’s punching the way a kid does, lots of anger, very little technique.” That seemed to me to describe a lot of the characters—especially the men—in your stories.

EK: If I had to describe my style of writing, I would say something close to that: a lot of emotions and very little technique. I think in the US, there is this concept of “the well-written story.” When I taught there I wanted to promote the concept of the badly-written good story, because when it comes to writing, professionalism is something I usually object to. When I talked to my students in the US, I would say to them: think about the stories you’ve heard in your life that have moved you the most. They were not usually told by the most articulate people. They were not, maybe, the best structured. It could be, like, a sweaty guy with a McDonald’s t-shirt, running down the street, and he says, “They’re killing the turtles! They’re killing the turtles!” It’s all about the power of the story, the passion behind it. I think with me, it’s always some kind of yearning or hopefulness, wrapped in barbed wire, with all kinds of booby traps.

BB: I’ve seen some people read your work as cynical.

EK: I think that I’m anything but cynical. For example, for me, “One Gram Short” is a story about a guy who falls in love with a girl, and who’s willing to go on this Via Dolorosa to fight dragons, just for the chance to have a moment with her. This is very romantic, very nice. The fact that the guy goes to a drug dealer to get something to impress her, and ends up making a deal with the drug dealer that involves him having to shout xenophobic things in a courtroom—that’s the barbed wire. But the heart of the story is all about love and romance, and this yearning for some intimacy, to be with somebody.

I think that my characters are all seeking something positive and good. I would say that this is true of all of humanity, or at least most of it. Even people who make other people suffer do it because they feel afraid or stressed, or they misread reality, or feel insecure.

BB: That reminds me of the story “A Glitch at the Edge of the Galaxy,” which is made up of emails between an escape room owner and a son who wants them to open it up on Holocaust Memorial Day for him and his mother, who’s a Holocaust survivor. On one level, the guy is being so rude, but on another, he just loves his mom and wants her to have a good day.

EK: I think that both of the characters are in some sense my alter egos. But the son in that story is, at least biographically, really very close to me. My mother is also a Holocaust survivor. Basically, I think that the fight is about who owns and controls memory, and what it means to respect Holocaust Memorial Day. Does it mean that on Holocaust Memorial Day you try to make Holocaust survivors feel good? Or does it mean that on Holocaust Memorial Day, nobody’s supposed to have fun? I think it’s a very legitimate argument. As a child, they would always have programs about the Holocaust on TV on that day. And I knew that this was a day where my parents would get totally depressed, and remember their siblings—or in my mother’s case, her parents—who were murdered, and would not sleep at night, and would be totally edgy. And as a child, I would say, “Why are they doing this to them?” They suffered so much. On Holocaust Memorial Day, they should show cartoons. You know? They should have sitcoms so they can handle it. But of course, this is a very subjective perspective, because most of the families didn’t go through the Holocaust, and they needed this day to be reminded of it.

BB: It feels like you write about the people who need to be reminded in “Yad Vashem.”

EK: That’s the story about a couple who are having a quarrel in Yad Vashem, and they break up there. The idea is, like, how can you feel sorry for yourself? How can you feel legitimized and angry when you are next to all these memories of horror? Imagine a couple fighting next to the Auschwitz exhibition in Yad Vashem, with one of them saying, “You selfish guy, you never pay for gas when we go to Yad Vashem.” You feel very petty, you know.

Growing up as a child with this shadow of the Holocaust, many times when I would hurt myself, as a kid, I would feel like it wasn’t legitimate for me to cry. If I fell off my bicycle and needed to have stitches in my head, I would say to myself, “My mother saw her mother killed in front of her eyes, so what am I doing now? I’m hurt and bleeding, but what is it compared to that?” What she went through justified tears, but what I was going through—it would be almost disrespectful toward her experience if I cried. The story “Yad Vashem” talks about how can you feel those little feelings in the shadow of something that is so powerful and horrible.

BB: That element runs through a lot of your work, which is often both very funny and also heartbreaking. Is creating that balance a conscious effort?

EK: It’s not a conscious decision. It’s something that I experience in real life. My mother has been losing her lucidity, so I can visit her and she won’t recognize me. And the feeling I have toward that situation . . . it’s always very complex and ambiguous. Because on one level, it’s heartbreaking: your mother doesn’t recognize you. This amazing woman who raised you all her life asks you for your name. But on another level, I can see that she lives in some kind of a present, and she’s not haunted by shadows of her past, and she doesn’t have any anxieties about the future, and though she doesn’t remember my name, she has this kind of vibe that I’m a nice guy, you know? I talk to her, and she says to me, “I see all the time that I don’t know anything. I can’t remember right now anything about stuff that I did in my life, but if everybody around me is so nice to me, I must’ve done something good.” She’s not who she used to be, but in some sense, she’s enlightened. She’s living in the present. So I feel that, many times, my experience of things can be very confusing. I’m not sure if my mom is the perfect example.

BB: I’m not sure there is a perfect example.

EK: I can tell you this: I fell downstairs in Brussels about two and a half months ago. It was a very, very bad fall. I kind of flew off, it was pretty high, and I hit the floor with my face. I was lying on the floor, and first I was feeling my face and my face was complete and in one piece, and I checked my teeth and my teeth were okay, and I couldn’t step because I sprained my ankle. And so I started yelling for help. And this kind of elderly, suspicious Brussels guy opened the door, and he says, “What happened?” And I said, “I fell. I hurt my foot. I’m in great pain.” And he looked at me suspiciously and he said, “So why are you smiling?” And I said, “Because I didn’t break my teeth.” You know? This kind of life experience is always spraining your ankle and being happy you didn’t break your teeth.

Bradley Babendir is an editor-at-large at Chicago Review of Books. His work has been published by NPR, TheWashington Post, The Paris Review, Pacific Standard, and elsewhere.