American Blood Libel

In The Accusation, historian Edward Berenson tells the story of an age-old antisemitic canard’s sole appearance in the United States.

Discussed in this essay: The Accusation: Blood Libel in an American Town, by Edward Berenson. W.W. Norton & Company, 2019. 256 pages.

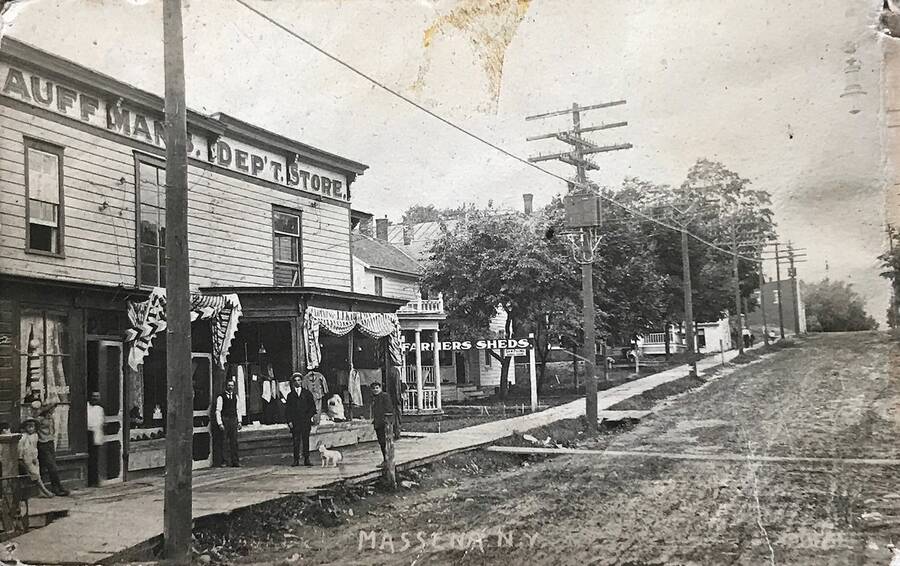

IN LATE SEPTEMBER, 1928, a four-year-old girl named Barbara Griffith went missing. More than 300 citizens of Massena, New York, the upstate town where Griffith lived, immediately organized search parties, thoroughly scouring homes and the nearby woods. But despite their desperate efforts, which lasted all night, they could not locate her. Amid that chaos, a rumor with no verified source began to spread: that Griffith was the victim of ritual murder by members of the town’s Jewish community who needed the blood of a Christian child for religious purposes. The accusation was repeated by the mayor, W. Gilbert Hawes, and by state troopers working on the case. It didn’t dissipate even when Griffith returned a little over 24 hours after she’d disappeared, shaken but unharmed, and everyone learned that she had simply gotten separated from her brother and slept in a nearby field when she was unable to find her way home; instead, the accusation evolved to allow for her safe return and continued to spread.

This incident constitutes the only documented instance of blood libel—a persistent antisemitic canard in which Jews are accused of using Christians’ blood for a religious ritual, deployed as a pretext for persecuting Jews, most commonly in Europe—in the history of the United States. Historian Edward Berenson’s new book, The Accusation: Blood Libel in an American Town, tells the story of this episode and its spiraling consequences. He seeks to understand why this happened and why it hasn’t happened again in the US. A Massena native, Berenson’s writing about the town is often characterized by a palpable sense of disappointment over both how the town handled the situation at the time and what the town has become in the present day (epitomized, for him, by Massena’s St. Lawrence County going for Trump in 2016). This mode stands in marked contrast with the way he writes about the details of the incident itself, which unfolds with the sizzle of a zeitgeisty true crime book. But both of these elements are something of a Trojan horse for a digressive historical survey of blood libel around the world, and a briefer consideration of the political climate for Jews in early 20th-century America.

Berenson begins his historical overview of blood libel cases with the first documented instance in 12th-century England and writes up to its emergence in Eastern Europe and the Middle East after World War II. That initial blood libel was uttered in 1144 by Thomas of Monmouth, a monk who allegedly heard of a case in which Jews had ritually murdered a Christian child as part of a continued practice. The source of this report was said to be a figure named Theobald, described by Thomas of Monmouth via Berenson as a “disillusioned Jew who had converted to Christianity.” But at the time of the reported murder, Theobald was nowhere near Norwich, where it had supposedly taken place, meaning he could not have witnessed it.

The addition of the claim of religious importance of Christian blood itself didn’t occur until nearly a century later, in Fulda (in what is now Germany), with an accusation that arose seemingly independently from the British account. After five children died in a fire on Christmas Day in 1235, local Jews were accused of killing them to harvest their blood for some ritual purpose. From here, Berenson provides a survey of European instances of blood libel from 1235 to the beginning of the 20th century. He describes how the situation for Jews in Europe worsened, with violence rising. Jews were often seen as harbingers of the wrong kind of change. By the late 19th century, Berenson writes, as business owners struggled through economic downturn, their financial fears “dovetailed with fears on the part of religious traditionalists and other conservatives that society was changing too quickly, that capitalism and liberalism had disrupted once-stable values, and that the Jews, as exemplars of the liberal, capitalist economy, had become too influential.” This led, Berenson argues, to the 79 cases of blood libel documented in Europe in the 1890s.

At times this litany of cases can feel like a lengthy distraction from the American incident that is his stated subject, but Berenson’s goals are worthwhile: to demonstrate the way that antisemitism developed throughout European history—treating it not as a mysterious ether that polluted European air, but as a social and political force actively cultivated by powerful people—and to help his reader understand the prevalence, function, and brutal consequences of blood libel in the European context. Berenson thus establishes that blood libel is an essential element of the history of European antisemitism, while by contrast, there is a total “absence in the United States of any social memory of ritual murder,” which, in his view, makes the emergence of even the single instance of the Massena accusation confusing.

Why did American antisemitism—though still pernicious—develop into such a comparatively mild force, considered alongside Europe? Berenson partially credits the power of the Jewish organizations founded in the early 20th century, which worked to resist it. These are precisely the forces that came to bear on the Massena case and its aftermath. After the digression into European history, Berenson spends most of The Accusation chronicling the ways that competing Jewish organizations battled against antisemitism—and against one another in its aftermath, each chasing credit for most effectively combating antisemitism.

Shortly after the blood libel accusation materialized, Wille Shulkin, son of a Massena-area synagogue president, contacted the American Jewish Committee (led by Louis Marshall) and then the American Jewish Congress (led by Rabbi Stephen Wise) to ask for help. It’s not clear why Shulkin involved both leaders, but Berenson’s theory is that Marshall’s initial response was too tepid, as he opted to spend time and energy investigating before vocally siding against those perpetrating the blood libel. While Marshall hemmed and hawed, Wise was more decisive, writing to Shulkin, “This thing must be cleared up and cleared up immediately and fully. The Jewish members of your community and we shall not rest content until there be the most ample and unequivocal apology . . . I do not propose to let this matter rest until there be the fullest explanation on the part of those responsible.”

Berenson sees their divergent responses as significantly linked to their political affiliations. Marshall and the American Jewish Committee were aligned with Republican President Herbert Hoover, whereas Wise and the American Jewish Congress were aligned with Al Smith, the governor of New York and Democratic candidate for president. The Jewish population of New York was a critical demographic for Smith, already an underdog, which incentivized swifter action. Smith and Wise worked together to extract apologies from both the mayor and the state police. But in an ironic twist on how each man entered into the matter, Marshall refused to relent when Smith and Wise did. After they had already accepted an apology from the offending parties, Marshall pushed forward, refusing to accept the apology as written, demanding revision or resignation, and called Hawes—the Massena mayor who repeated the blood libel—“infinitely worse” than known antisemite Henry Ford. Wise and Smith worried that by failing to accept the apology, Marshall would “enflame rather than calm ethnoreligious antagonisms.”

Berenson clearly feels that the cautious approach—exemplified first by Marshall, and then by Wise—was the right one, and he emphasizes that Smith and Wise seemed to have a better sense of the potential threat that lurked ahead of them. (Specifically, both worried that seeking further consequences against the perpetrators of the blood libel might inflame the KKK, who would then lash out violently against Jews in the region.) Berenson seems to think that, even if one didn’t believe that the mayor and state troopers were genuinely remorseful, the risk that pressing on would result in some sort of retaliation outweighed any material benefits of a more complete victory; indeed, Berenson never appears convinced such benefits exist. Reading The Accusation in the wake of the recent horrifying antisemitic violence in New York, one might be tempted to draw from Berenson’s analysis a general principle of caution in response to antisemitism. But such an abstraction would be misguided. The specific circumstances of the Massena case are central to Berenson’s judgment of the situation.

In Berenson’s view, the story of The Accusation is worth telling and engaging with because the Massena incident is the only documented blood libel case in American history. But what does this singularity really mean? Ultimately, Berenson treats it as little more than an anomaly. But the European example, which Berenson has gone to great lengths to reproduce, suggests it could hypothetically be the first sign of a developing phenomenon: it’s striking that the amount of time between the first European blood libel in 1144 and the first that made a claim of religious importance in 1235 is 91 years—the same as the span between 1928 and the publication of The Accusation. Compared to its European counterpart, American antisemitism may be in its early stages, even today. Accordingly, we still lack rigorous, coherent theories answering the question: What is American antisemitism? That The Accusation brings the urgency of this question to the fore is the book’s defining strength; that it doesn’t attempt an answer, its defining weakness.

Bradley Babendir is an editor-at-large at Chicago Review of Books. His work has been published by NPR, TheWashington Post, The Paris Review, Pacific Standard, and elsewhere.